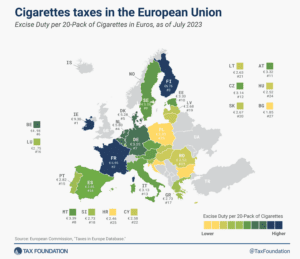

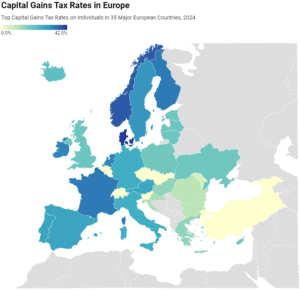

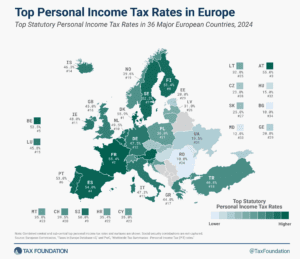

Top Personal Income Tax Rates in Europe, 2024

Denmark (55.9 percent), France (55.4 percent), and Austria (55 percent) have the highest top statutory personal income tax rates among European OECD countries.

3 min readProviding journalists, taxpayers and policymakers with basic data on taxes and spending is a cornerstone of the Tax Foundation’s educational mission. We’ve found that one of the best, most engaging ways to do that is by visualizing tax data in the form of maps.

How does your country collect revenue? Every week, we release a new tax map that illustrates one important measure of tax rates, collections, burdens and more.

Denmark (55.9 percent), France (55.4 percent), and Austria (55 percent) have the highest top statutory personal income tax rates among European OECD countries.

3 min read

A few European countries have made changes to their VAT rates, including the Czech Republic, Estonia, Switzerland, and Turkey.

3 min read

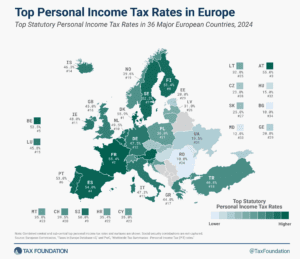

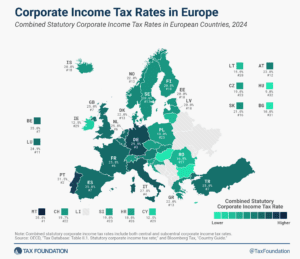

Like most regions around the world, European countries have experienced a decline in corporate income tax rates over the past four decades, but the average corporate income tax rate has leveled off in recent years.

2 min read

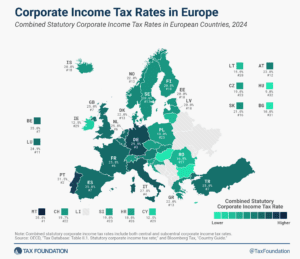

The aim of patent boxes is generally to encourage and attract local research and development (R&D) and to incentivize businesses to locate IP in the country. However, patent boxes can introduce another level of complexity to a tax system, and some recent research questions whether patent boxes are actually effective in driving innovation.

3 min read

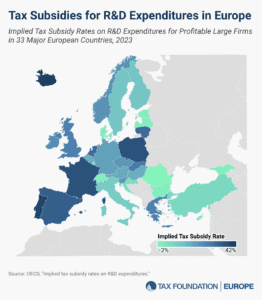

Many countries incentivize business investment in research and development (R&D), intending to foster innovation. A common approach is to provide direct government funding for R&D activity. However, a significant number of jurisdictions also offer R&D tax incentives.

3 min read

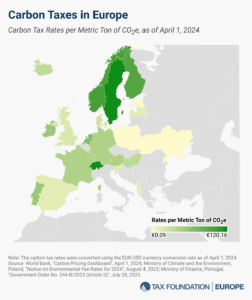

23 European countries have implemented carbon taxes, ranging from less than €1 per metric ton of carbon emissions in Ukraine to more than €100 in Sweden, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland.

3 min read

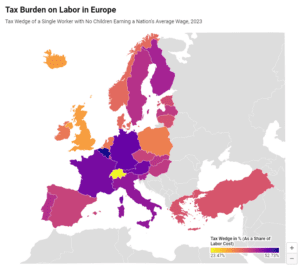

To make the taxation of labor more efficient, policymakers should understand the inputs into the tax wedge, and taxpayers should understand how their tax burden funds government services.

4 min read

Governments often justify higher tax burdens with more extensive public services. However, the cost of these services can be more than half of an average worker’s salary.

16 min read

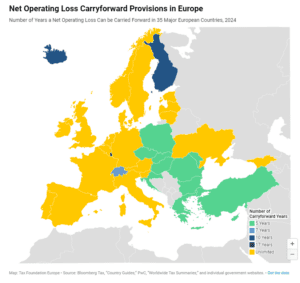

Carryover provisions help businesses “smooth” their risk and income, making the tax code more neutral across investments and over time.

3 min read

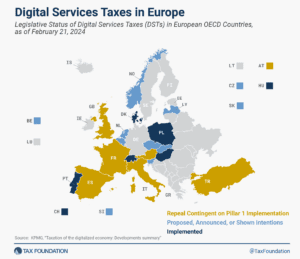

About half of all European OECD countries have either announced, proposed, or implemented a DST. Because these taxes mainly impact U.S. companies and are thus perceived as discriminatory, the United States responded to the policies with retaliatory tariff threats, urging countries to abandon unilateral measures.

4 min read

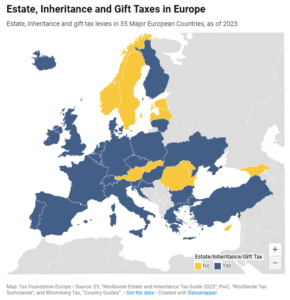

As tempting as inheritance, estate, and gift taxes might look—especially when the OECD notes them as a way to reduce wealth inequality—their limited capacity to collect revenue and their negative impact on entrepreneurial activity, saving, and work should make policymakers consider their repeal instead of boosting them.

2 min read

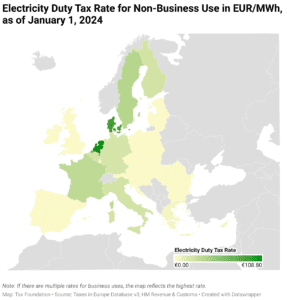

EU Member States should seek to minimize the rate and broaden the base of electricity duties, consolidating their rates to the required minimum rate.

3 min read

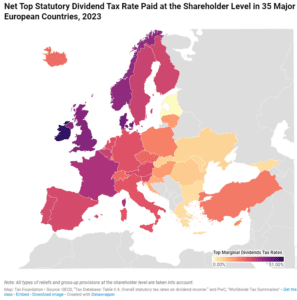

In many countries, corporate profits are subject to two layers of taxation: the corporate income tax at the entity level when the corporation earns income, and the dividend tax or capital gains tax at the individual level when that income is passed to its shareholders as either dividends or capital gains.

2 min read

In many European countries, investment income, such as dividends and capital gains, is taxed at a different rate than wage income.

2 min read

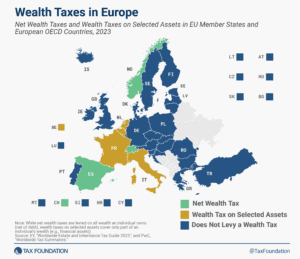

Only three European countries levy a net wealth tax—Norway, Spain, and Switzerland. France and Italy levy wealth taxes on selected assets.

4 min read

Denmark (55.9 percent), France (55.4 percent), and Austria (55 percent) have the highest top statutory personal income tax rates among European OECD countries.

3 min read

A few European countries have made changes to their VAT rates, including the Czech Republic, Estonia, Switzerland, and Turkey.

3 min read

Like most regions around the world, European countries have experienced a decline in corporate income tax rates over the past four decades, but the average corporate income tax rate has leveled off in recent years.

2 min read

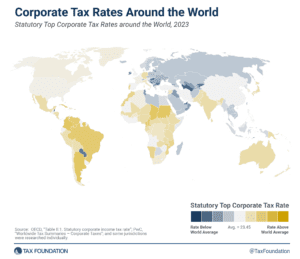

Of the 225 jurisdictions around the world, only six have increased their top corporate income tax rate in 2023, a trend that might be reversed in the coming years as more countries agree to implement the global minimum tax.

16 min read

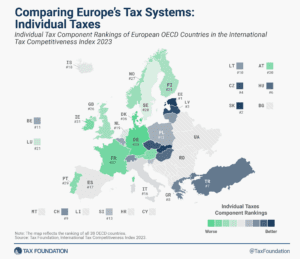

Estonia has the most competitive individual tax system in the OECD for the 10th consecutive year.

2 min read

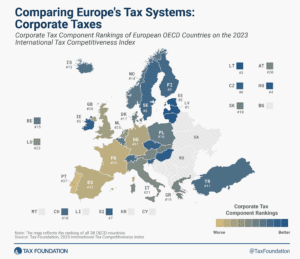

According to the corporate tax component of the 2023 International Tax Competitiveness Index, Latvia and Estonia have the best corporate tax systems in the OECD.

2 min read

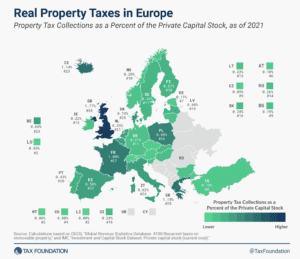

High property taxes levied not only on land but also on buildings and structures can discourage investment in infrastructure, which businesses would have to pay additional tax on.

2 min read