Yesterday afternoon I spoke on a panel in Austin, Texas at the Texas Public Policy Foundation’s annual policy conference. The panel was on what makes a competitive tax code, and of course, Texas’ taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code has a lot of desirable elements. The state ranks 10th overall in our State Business Tax Climate Index, and going without an individual income tax is a major contributor to why the state scores so well.

What holds the state back, though, is its franchise tax, most commonly called the Margin Tax. Take a look at how the Margin Tax factors into our State Business Tax Climate Index ranking (I’ve bolded two items to pay special attention to):

Table 1: 2016 State Business Tax Climate Index Rankings for Texas

|

Index Rank |

|

|

Overall |

10th |

|

Corporate |

41st |

|

Individual |

6th |

|

Sales |

37th |

|

Unemployment Insurance |

15th |

|

Property |

34th |

In our Index, and in the real world, the Texas Margin Tax sticks out like a sore thumb. The Margin Tax is captured in the corporate tax component score of 41st, and is additionally captured in the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. component, where the Margin Tax is so encompassing that it applies to LLC and S-corporation revenues, which are traditionally only the domain of the individual income tax. So instead of scoring 1st in that component for forgoing an individual income tax, Texas scores sixth. Here’s why the tax deserves so much criticism:

Problem #1 with the Margin Tax: It’s Complicated

As you can see from the figure below, the contortions required to calculate a Margin Tax bill are unusual. You start with four potential tax base calculations, picking the lowest of the four, then you apportion your income, then you have to determine whether you qualify for a preferential rate as a wholesaler/retailer, then you subtract out your credits. The last step is a minimum liability, where if after going through this exercise you yield a liability of less than $1000, you (or most likely your accountant) just wasted a lot of time, because you don’t actually owe anything.

The only other taxes I can think of with such a cumbersome calculation method like this are New York’s corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. , which had four bases, but was reformed in 2014, and the Michigan Business Tax, which was repealed and replaced with a well-structured corporate income tax in 2011.

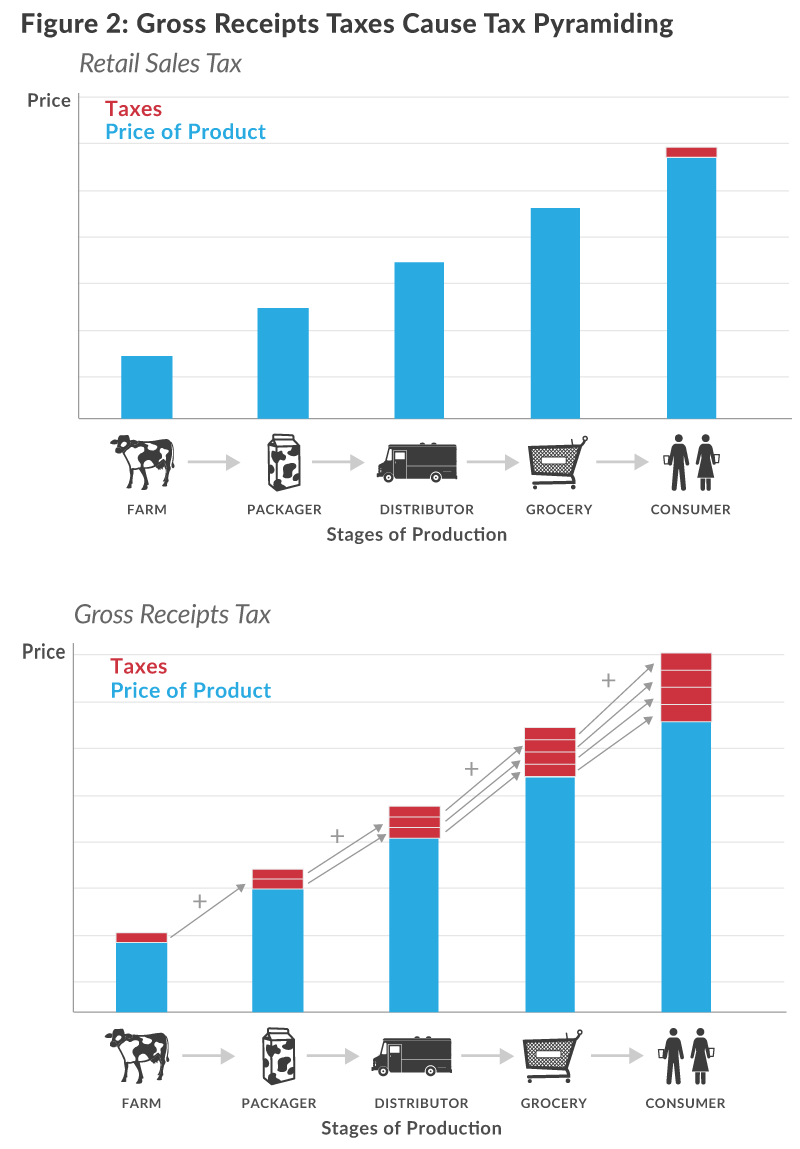

Problem #2 with the Margin Tax: Gross Receipts Taxes Pyramid

Gross receipts taxes are often criticized in the public finance field because they “pyramid,” or stack on top of each other as goods move through the production chain. Compared to a sales tax, which only is levied on the final sale of a consumer good, gross receipts taxes are levied every time a good or service changes hands, meaning they have a multiplicative effect with each new intermediate transaction in the making of a final good or service. The chart below shows how the production of milk is treated under a sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. regime versus a gross receipts taxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. regime.

While the Margin Tax is not a pure gross receipts tax, it starts from a base of total revenue and then allows only a few deductions, never quite getting to a base of income, and maintaining pyramiding elements. Indiana University Professor John Mikesell once aptly described the Margin tax as:

“a badly designed business profits tax, like those that emerged in the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union . . . combin[ing] all the problems of minimum income taxation in general—excess compliance and administrative cost, penalization of the unsuccessful business, undesirable incentive impacts, doubtful equity basis—with those of taxation according to gross receipts.”

Problem #3: Gross Receipts Taxes are Antiquated Tax Policy

Gross receipts taxes had their heyday in Europe prior to the 18th century. The most infamous gross receipts, or “turnover” tax of the time was the Spanish “Alcabala,” which Adam Smith notably criticized in the Wealth of Nations. It was repealed in 1845.

Tax scholar John Due categorically dismisses gross receipts taxes in his tax history book, Indirect Taxation in Developing Countries, saying, “the defects of the turnover tax have been made extremely clear by long experience and of course have been responsible for the abandonment of the tax by most countries.”

Gross receipts taxes are gone in most countries, yes, but have additionally been abandoned by most states in the US too, where currently only six states—Delaware, Ohio, Nevada, Texas, Virginia, and Washington—levy gross receipts or modified gross receipts taxes. In the last 15 years, Michigan, New Jersey, Kentucky, Indiana have repealed gross receipts taxes.

The Good News: Legislators in Texas are More Aware than They’ve Ever Been

This last legislative session in Texas was a successful one for cutting the Margin Tax—legislators reduced the rates from 0.95 percent on most businesses and 0.475 on retailers and wholesalers to 0.75 and 0.375 percent, and HB 32 even commented that it is “the intent of the legislature to promote economic growth by repealing the franchise tax.”

The Texas legislature convenes every other year, so there will not be action on the Margin Tax in 2016, but all signs point to the tax being a prominent item of discussion in the 2017 session.

Margin Tax Repeal and the State Business Tax Climate Index

Finally, repealing the Margin Tax fully would move Texas from 10th place in our Index to an impressive 3rd place, behind only Wyoming and South Dakota. The corporate and individual income tax components would improve to 1st.

Table 2: State Business Tax Climate Index Rankings, Current Law vs. Margin Tax Repeal

|

Current Law |

With Margin Tax Repeal |

|

|

Overall |

10th |

3rd |

|

Corporate |

41st |

1st |

|

Individual |

6th |

1st |

|

Sales |

37th |

37th |

|

Unemployment Insurance |

15th |

15th |

|

Property |

34th |

34th |

Be sure to check out our comprehensive special report on the Texas Margin Tax, and the most recent research on the Margin Tax from the Texas Public Policy Foundation.

Share this article