State taxation finally has its own viral sensation—and, unsurprisingly, it’s a CAT.

No, not the feline version, but the Commercial Activity TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. (CAT), Ohio’s 2005 spin on gross receipts taxation, which is suddenly the model for every other state thinking about bringing back that once-moribund and outmoded form of taxation. No one wants one of those old business and occupation taxes; they belong to the distant past. But a CAT? Why, CATs get shared.

The bad news? Living under the CAT’s foot isn’t a very good thing.

West Virginia came close to adopting a tax based on Ohio’s CAT earlier this year. Proponents of a gross receipts taxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. in Oregon leaned heavily on the CAT to defend their proposal. Louisiana considered one. And, most recently, the Missouri Director of Revenue signaled the administration’s interest in a gross receipts tax modeled after the CAT in a speech last week.

Gross receipts taxes (GRTs) used to be everywhere, but most were repealed over the course of the 20th century. By 2002, there were only two statewide gross receipts taxes left standing, in Delaware and Washington. The defects of GRTs were almost universally acknowledged.

By taxing gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total of all income received from any source before taxes or deductions. It includes wages, salaries, tips, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental income, alimony, pensions, and other forms of income. For businesses, gross income (or gross profit) is the sum of total receipts or sales minus the cost of goods sold (COGS)—the direct costs of producing goods, including inventory and certain labor costs. , these taxes were indifferent to profitability and thus to ability to pay, and heavily penalized new firms, those with narrow profit margins, and those posting actual losses. They were imposed at each stage of the production process, meaning that tax was imposed upon tax in what is commonly called “tax pyramiding,” the result being that the final product contains multiple layers of taxation. Under gross receipts taxes, businesses experienced vastly different effective tax rates, creating a system widely acknowledged as inequitable and economically destructive. State after state scrapped this outmoded form of taxation.

But everything old is new again (witness the reemergence of Archie and Florence as popular baby names), and through the CAT, gross receipts taxes have a new lease on life.

The Ohio CAT is often held up as a success story, mostly due to the fact that it doesn’t engender the sort of business backlash that other states have experienced. The perceived success of the CAT is a large part of the case for a new gross receipts tax in Missouri, based on documents leaked from the state’s tax commission earlier this year. (A final report is still forthcoming, but based on recent public comments, it is likely to recommend a GRT.)

The problem is that the CAT isn’t anywhere near the success that proponents like to think. To understand why, you need to know the circumstances under which it was introduced, because a significant factor in acceptance of the Ohio CAT is what it replaced. Prior to an overhaul of the tax code which commenced in 2005, Ohio imposed both a corporate franchise tax (a corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. with a capital stock tax component) and a tangible personal property tax. Changes to the tax code adopted that year reduced the individual income tax rate and phased out the taxation of corporate income, capital stock, and tangible personal property.

The package represented a significant tax cut overall. In inflation-adjusted terms, it represented a reduction of 23.6 percent in revenue from the affected taxes.

Economists generally regard capital stock taxes, tangible personal property taxes, and gross receipts taxes as more economically harmful than corporate income taxes (though they are distortive as well), so in creating the CAT, Ohio replaced three economically distortive taxes with one, and this in the context of a sizable tax cut.

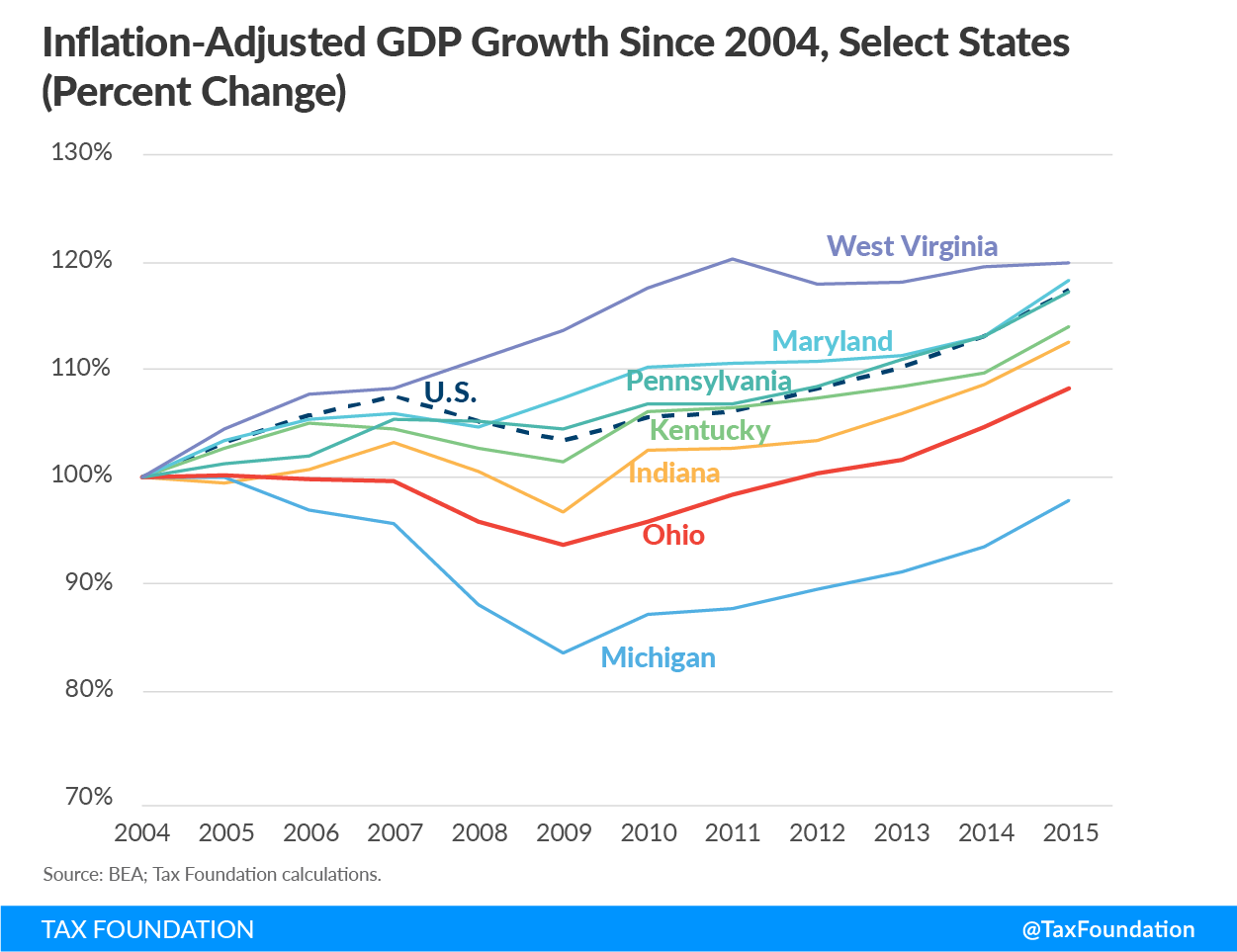

Ohio is not a clear success story to begin with: since 2004, it has still grown more slowly than all neighboring states except Michigan, which was hit particularly hard by the Great Recession. But if the lack of unified opposition to the tax is a success, then this is less an endorsement of gross receipts taxes than a commentary on just how bad the previous system was, and it is not analogous to swapping out a traditional corporate income tax for a gross receipts tax, as is being contemplated in Missouri, or tacking one onto the existing corporate income tax, as Louisiana and West Virginia considered.

For a detailed analysis of the Ohio CAT and why it doesn’t provide a good model for other states to follow, click here to read our new paper on the subject. As we conclude there:

“The resurgence of interest in gross receipts taxation is a throwback in the worst sense, the embrace of an inefficient and inequitable tax long since superseded by more modern revenue tools. Ohio’s experience, at most, offers a cautionary tale about capital stock and tangible personal property taxes, not a recommendation of gross receipts taxes. By learning the wrong lessons from the Buckeye State, other states risk embarking on a perilous course. Proponents hope the CAT has many lives—but for this CAT, even one life is one too many.”

Share this article