As the deadline for the 2022 tax filing season nears, the IRS faces scrutiny for its backlog of returns, inaccessible taxpayer service, and delays in issuing certain refunds. As of January 28th, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) had 23.7 million returns awaiting action, compared to a typical backlog at that point of roughly 1 million returns. IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig recently testified the IRS will catch up on the return backlog by the end of the year by creating surge teams and planning to hire an additional 10,000 workers, but that will do little to alleviate the pain of this year’s filing season ending in less than a month.

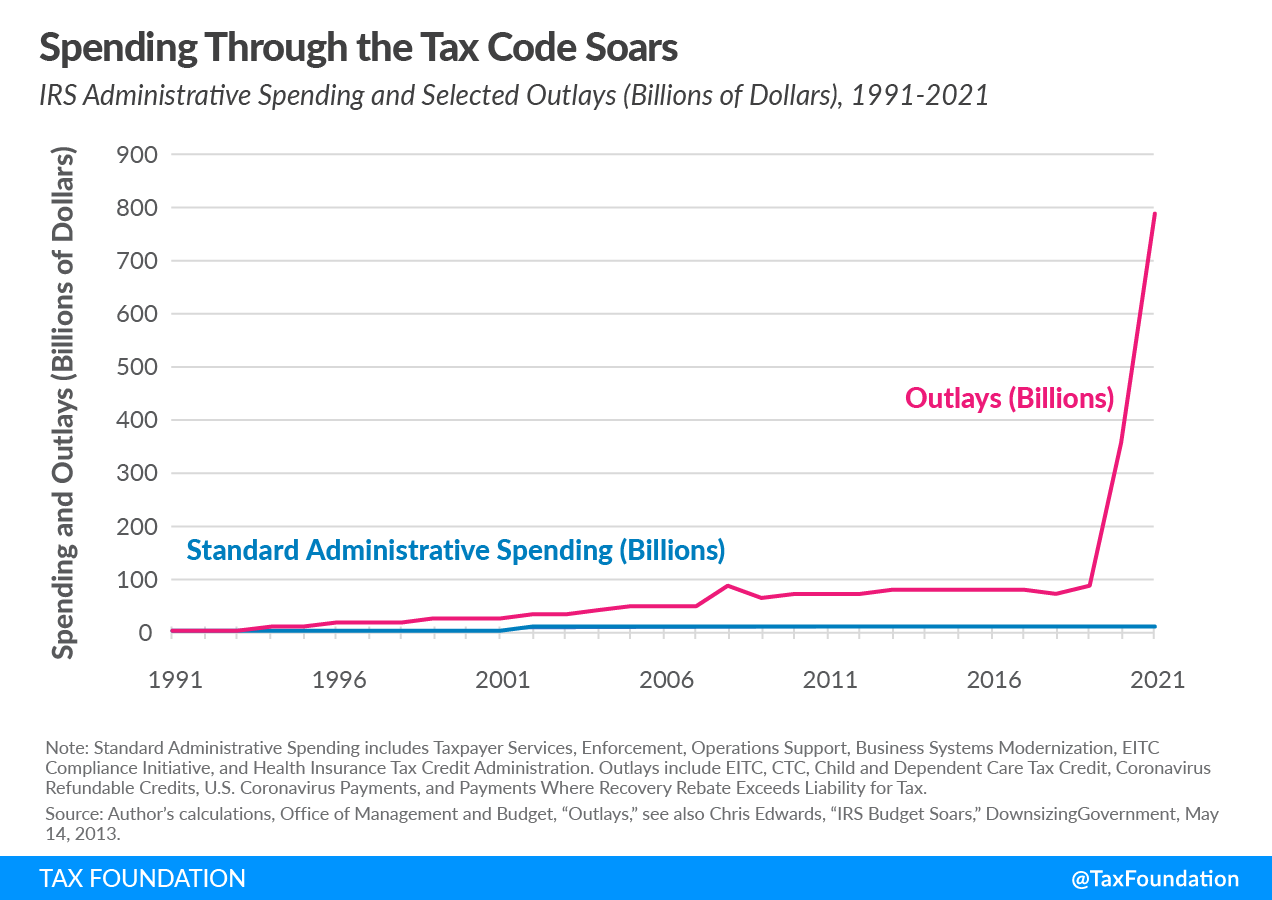

In many ways the current chaos is the culmination of a problematic trend in fiscal policy. For the past few decades, policymakers have increasingly relied on the taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code to deliver major social spending initiatives, adding benefits administration to the IRS’s normal responsibilities as a revenue collection agency. At the same time, IRS capacity has not expanded enough to match its major new responsibilities. In the long term, the most stable solution is to move social spending out of the tax code and let the IRS focus its resources on revenue collection.

In his 1996 State of the Union Address, Bill Clinton famously said, “The era of big government is over.” But policymakers did not just abandon their social and welfare policy goals. The full context of his quote: “…the era of big government is over. But we cannot go back to the time when citizens were left to fend for themselves.”

Politicians were in a difficult spot: they had social policy goals, taxes were unpopular (just ask former president George H. W. Bush), and the political environment was unfriendly to more government spending. The apparent solution was to turn social policy into tax cuts. By creating new tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. s in lieu of traditional welfare programs, expansions of the social safety net could be framed as tax cuts.

The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 included several reforms to the tax code, the most prominent being the creation of the Child Tax Credit (or CTC). The CTC was partly a fix to better adjust the tax code for household size, but support for American families was the core motivation for its creation. Over the past 20 years, policymakers have made the CTC more generous by increasing its size and refundability. And the CTC is only one of many tax credits added to the IRS’s responsibility including health care (e.g., the Affordable Care Act’s Premium Tax Credit), education, housing, energy, and the environment.

Over the same approximate period, the IRS has faced significant political heat, although not always unjustifiably. So as the responsibilities of the IRS grew, the political will to raise its budget weakened. As is often cited, from 2011 to 2020, the IRS’s budget declined by roughly 20 percent after adjusting for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. . But refundable tax creditA refundable tax credit can be used to generate a federal tax refund larger than the amount of tax paid throughout the year. In other words, a refundable tax credit creates the possibility of a negative federal tax liability. An example of a refundable tax credit is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). s (payments the IRS makes when the value of a credit exceeds tax liability) have soared.

Enter the pandemic.

All three major rounds of relief legislation (the CARES Act in March 2020, the Consolidated Appropriations Act in December 2020, and the American Rescue Plan in March 2021) relied heavily on the tax system to distribute pandemic relief. For example, three rounds of economic impact payments were administered as tax credits; the CTC was expanded and temporarily converted into a monthly payment; the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) used a look-back formula; and the first $10,200 in unemployment compensation in 2020 was excluded for certain taxpayers.

The IRS received additional funding to administer the pandemic relief programs, but the relief programs stretched well beyond the IRS’s capacity. While the IRS experienced a reduction of in-person meetings from 752,000 in 2019 to 374,000 in 2021, it was more than offset by an uptick in phone calls—the agency received 195 million calls in the 2021 filing season, relative to just 36 million in the 2019 filing season. (In fact, frustrated taxpayers have even called the Tax Foundation for help because no one at the IRS is available to answer their questions.)

Low-income earners are often impacted the most by poor IRS service. For example, low-income households earning less than $25,000 were least likely to hear about recent changes to the CTC and must navigate these changes without one-on-one IRS support. Many of these households may not regularly file tax returns, making it even harder for them to claim benefits administered through the tax code.

The stretched IRS is a product of the structural choice to put it in charge of delivering social benefits. Erin Collins, the IRS’s Taxpayer Advocate, said the IRS’s “telephone service was the worst it has ever been” in 2021. And as Collins noted in her Annual Report to Congress this year:

“Each financial relief program consumed considerable IRS resources to administer, including overall planning, information technology (IT) programming, implementation, public communications, and responding to taxpayers’ questions and account issues. To address these needs, the IRS had to reallocate resources from its core tax administration responsibilities.”

In the short term, the solution includes ramping up temporary hires and pulling back the barriers that slow hiring. Now, one might suggest ramping up the IRS’s capacity dramatically and permanently so it can effectively serve as both a benefits agency and a tax collection agency in the long term. But such approach has at least two issues: spending agencies, rather than the IRS, should be responsible for administering benefits subject to the appropriations process, and the IRS’s status as a political football makes its budget less reliable. Even in the short term, ramping up capacity will be challenging as the IRS is already facing hiring shortfalls for open roles.

Bigger picture, the current crisis should draw the need for fundamental tax reform into clearer focus. Simplifying and reducing social benefits in the tax code would make it easier for the IRS to focus on its primary mission: collecting revenue for the federal government.

For example, replacing the Child Tax Credit with a monthly child allowance administered by the Social Security Administration would let the IRS do more with the budget it currently has. Relieved of the burden of being both America’s tax collection agency and social benefit distribution agency, the IRS could make much-needed long-term investments in information technology and efficiency.

Ultimately, moving social policy out of the tax code makes sense from a tax policy perspective, a benefits policy perspective, and a tax administration perspective.