On corporate taxation, Ireland ranks 4th among countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in our 2018 International Tax Competitiveness Index. With a corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate of 12.5 percent, Ireland not only has the second lowest rate in the OECD (behind Hungary at 9 percent), it has one of the lowest corporate income tax rates in the world. With such a low rate, Ireland regularly appears in articles describing the state of tax competition as other countries move toward its level. In the past, U.S. multinational corporations have inverted to become Irish corporations to take advantage of the corporate tax provisions there.

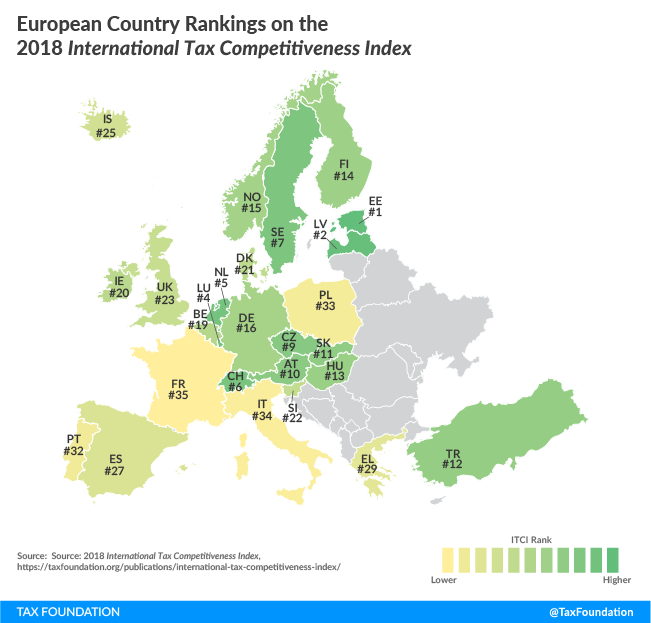

A competitive taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code is about more than a low corporate rate, though. Despite ranking well on corporate taxation, Ireland ranks 20th out of 35 OECD countries on the overall ranking. As I will describe further, this is due to poorly designed policies for taxing personal income and consumption.

[global_newsletter_inline_widget campaign=”//TaxFoundation.us1.list-manage.com/subscribe/post?u=fefb55dc846b4d629857464f8&id=6c6b782bd7&SIGNUP=ITCI”]

On personal income taxes, Ireland ranks 33rd out of 35 countries, ahead of just France and Israel. Because of the progressive nature of its personal income tax and the top rate on income of 52 percent (including payroll taxes), the economic cost of raising an extra euro from labor taxes in Ireland is 1.68, second highest in the OECD.

The dramatic difference between the tax burden that the average worker faces and that of top earners impacts the decisions that workers and employers make. For workers, it can impact decisions to work more and lose a larger fraction of one’s paycheck to taxes. For businesses, it raises the cost of hiring.

Ireland also has the highest tax rate (51 percent) on dividends received by individuals among OECD countries. A high dividend tax rate at the personal level could arguably be used to offset revenue losses from the low corporate rate, but the current Irish system relies on taxing corporate income twice. Instead of taxing income twice, Ireland could follow the path some countries have taken to integrate their taxation of corporate income so that business profits are only taxed once.

Ireland also ranks relatively low on consumption taxes at 23rd out of 35. Ireland’s relatively high VAT rate of 23 percent covers less than half of the potential tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , revealing some problems with its system. Part of low share of potential revenue collected is due to the VAT gap; Ireland did not collect 11 percent of the VAT owed in 2016 because of tax evasion and inadequate collection.

However, some consumption is not taxed by design. A variety of goods and services is not subject to the 23 percent rate or is fully exempt from VAT in Ireland. Some of the exemptions or reduced rates apply to narrow bands of consumption. For instance, undecorated wax candles and cut flowers are fully exempt, and routine cleaning of immovable property and minor repairs of bicycles see a reduced rate of 13.5 percent. Various kinds of foods see either reduced (13.5 percent) or super reduced (9 percent) rates, and some are fully exempt from VAT.

Every exclusion increases the necessary rate to raise the revenue the Irish government expects to receive from its VAT. This creates larger distortions than necessary—both for the goods that face the full VAT rate and for the products that face exemptions. Individuals and families purchase goods and services subject to the various rates at different times—lower rates overall and fewer exemptions or reduced rates would help minimize the impact of the VAT for consumers.

Is the Irish tax code competitive? When it comes to taxing corporate income, the answer is “yes,” but personal income taxation and consumption taxes could benefit from several improvements.

Policymakers in Ireland should not be satisfied with having just a competitive corporate tax code. Fixing the impact of high marginal rates on personal income and applying the VAT to a broader base could greatly improve the taxes that individuals and families face and improve the overall competitiveness of the system.

Share this article