Health taxes have become a major focus of global organizations interested in taxation. The United Nations drafted a goal for 80 percent of countries to implement the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages by 2030. While well-designed excise taxes can make society better off, some of the health taxes proposed by the WHO use a pretty façade to cover for policies that fail to deliver their promised benefits.

Proponents of health taxes claim they are win-win policies: they generate revenue for government and discourage the consumption of unhealthy products, thus improving public health. For brevity’s sake, we will ignore the first claim that applying a taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. simply to create revenue for the government to then spend automatically improves well-being—because this is highly debatable. The second “win” has some merit, as taxes on certain products can encourage consumers to make healthier decisions. Using tax policy to improve public health has limits, however, and a sound design is paramount.

Tax design has a substantial impact on policy outcomes. We’ve previously detailed how well-designed taxes generate revenue with far less negative societal impact than poorly designed taxes. Some general rules relevant to the implementation of health taxes are that the excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. (base) should target the harm-causing element, and neutral taxes will minimize market distortions, consumer substitution, and tax avoidance.

To achieve the policy goal of raising revenue while reducing harm from alcohol consumption, for example, alcohol excise taxes should target beverage alcohol content. The more alcohol in a drink, the heavier the tax applied to that product. This system is transparent and targets the externalityAn externality, in economic terms, is a side effect or consequence of an activity that is not reflected in the cost of that activity, and not primarily borne by those directly involved in said activity. Externalities can be caused by either the production or consumption of a good or service and can be positive or negative. -causing ingredient: alcohol. This isn’t the system commonly used, unfortunately.

Most countries use a categorical system where beverages are placed into categories—beer, wine, spirits, and others—and then taxed based on the category. Some of those categories apply taxes based on alcohol content within the category, but content-based alcohol taxation stops at the category lines. Categorical tax systems have difficulty adapting to new products and those outside traditional category lines (e.g., ready-to-drink cocktails), and they almost always favor one alcoholic beverage over another. Roughly half of the EU Member States don’t apply an excise tax to wine, for example. This encourages drinkers to consume the low-tax or untaxed products, negating both the revenue and decreased consumption goals of alcohol taxes.

These taxes should also be simple, ideally levied early in the production chain to limit tax compliance and enforcement costs. A tax proposal in Mexico, where more than 40 percent of spirits products are sold “informally” (untaxed), is estimated to increase tax collections substantially without any tax rate changes by reducing the number of tax remitters more than 99 percent by charging the tax to producers and importers, rather than requiring VAT-like tax remission by manufacturers, distributors, and retailers.

Unfortunately, even the best health taxes face limitations. When the tax design is suboptimal, those limitations are more pronounced. This post highlights two key limitations of health taxes’ ability to raise revenue and improve public health.

1. Behavior and substitution can nullify potential health effects.

Taxes may discourage consumption of a targeted product, but evidence suggests that substitution effects limit effects on overall health. Beverage taxes highlight this limitation.

The academic consensus surrounding sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) taxes is that they have resulted in no discernable impact on obesity or body weight. Even though an SSB tax is effective at reducing sugary beverage consumption, without other changes to diets, exercise, or lifestyle, the result has been no overall effect on a population’s rate of obesity. In Italy, for instance, historical obesity rates have remained stable despite reductions in per capita soft drink sales.

Tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. considerations are worth mentioning here again. Similar to the way distortive alcohol taxation encourages consumers to find lower-taxed alcoholic beverages, SSB taxes allow consumers to find lower-taxed products to consume without changing their overall sugar or caloric intake. A tax based on added sugar in all products—not just selective beverages—would have a much greater impact on total sugar consumption.

2. Health taxes often poorly target problematic behavior.

Health taxes act as a mild deterrent to consumption but do almost nothing to address underlying issues linked to addictive behavior or the negative consequences that result from consumption of these products. Taxes on alcohol, for example, don’t address alcoholism or drunk driving other than by making legal alcohol consumption more expensive—an overall insufficient deterrent for most alcoholics.

All drinkers have to pay the tab for the alcohol tax, though the top 10 percent of drinkers consume nearly three-quarters of all drinks. Moderate drinkers are highly unlikely to inflict costs on society, while heavy drinkers are considerably more likely to do so. Harm increases exponentially with alcohol consumption.

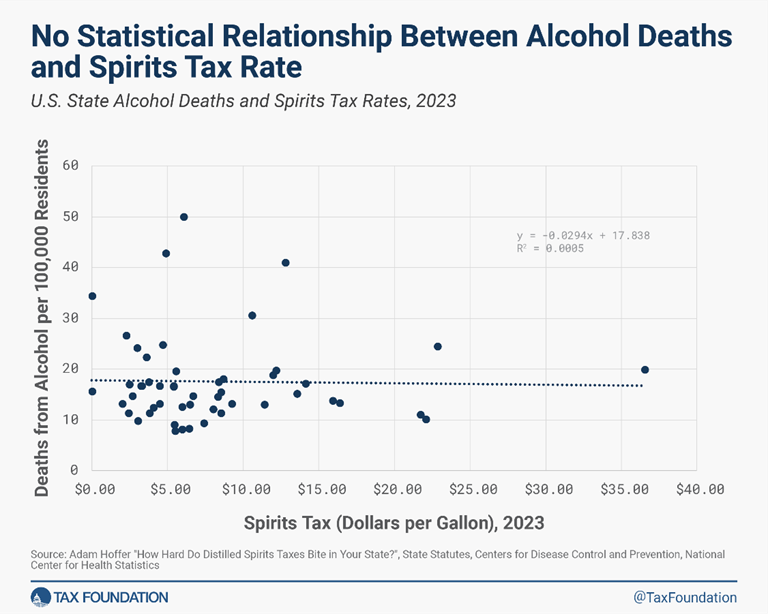

- Data from US states show no statistical relationship between alcohol deaths and spirits tax rates, for example. At the margin, higher taxes discourage consumption, but the data show that simply increasing excise taxes on alcohol doesn’t solve the problems associated with drinking.

This doesn’t mean that all excise taxes should be scrapped. They may be effective on the margin, but sky-high rates don’t solve all problems. Before running to levy exorbitant tax rates on undesirable consumption products, policymakers should prioritize improvements to their existing excise tax design. Building on a poor tax design foundation is a recipe for ineffective tax policy that will need to be rebuilt.

The place for this policy work to occur is within national governments. Top-down blunt global policies lack the local knowledge essential to maximize the effectiveness of health taxes. National sovereignty will also promote policies that can be supported by a country’s tax administration and enforcement systems.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe