The debate in Washington, D.C. often centers around tax expenditures, so-called corporate loopholes, in the taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code. But not all tax expenditures are created equal. Some represent neutral tax treatment and should be left alone, while others are distortionary and should be repealed. Understanding what a tax expenditureTax expenditures are a departure from the “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses, through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. Expenditures can result in significant revenue losses to the government and include provisions such as the earned income tax credit (EITC), child tax credit (CTC), deduction for employer health-care contributions, and tax-advantaged savings plans. represents is essential for understanding how our tax code works for both businesses and individuals.

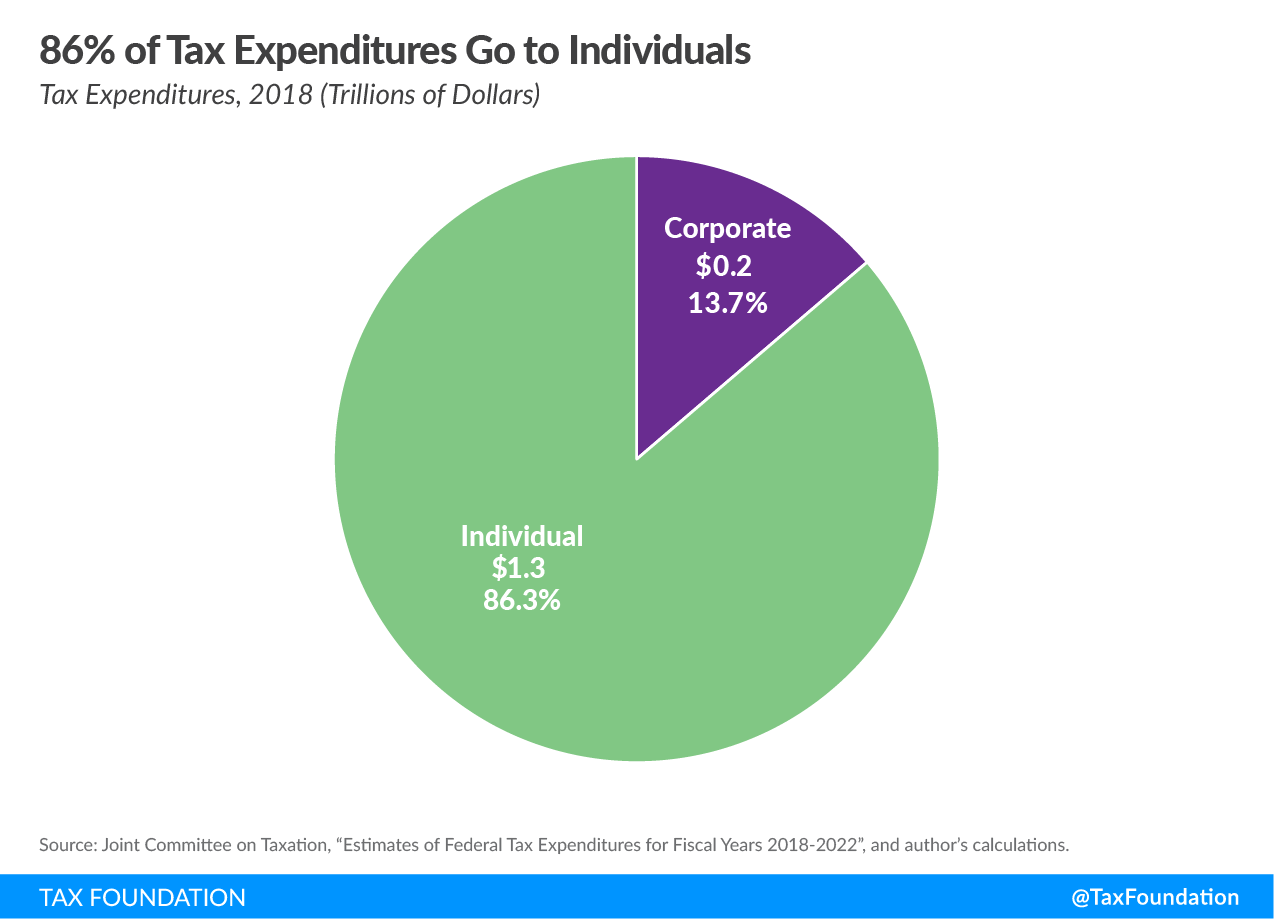

The following chart shows the relative size of corporate and individual tax expenditures. According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, individuals received 86.3 percent of tax expenditures in 2018, or $1.3 trillion. Corporations received only 13.7 percent of all tax expenditures, or $0.2 trillion ($200 billion). In total, tax expenditures had an estimated value of $1.5 trillion in 2018.

Many tax expenditures provide preferential treatment for particular economic activities, making the tax code less neutral and shrinking the tax base. However, some are broad-based changes that play an important role by moving the U.S. toward a different tax system. Simply eliminating expenditures across the board would therefore be misguided.

A further complication is that what counts as a tax expenditure depends on what qualifies as the “normal” tax code. For example, the Joint Committee on Taxation considers depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. to be an expenditure, but this is a questionable treatment following from the common but flawed Haig-Simons definition of income.

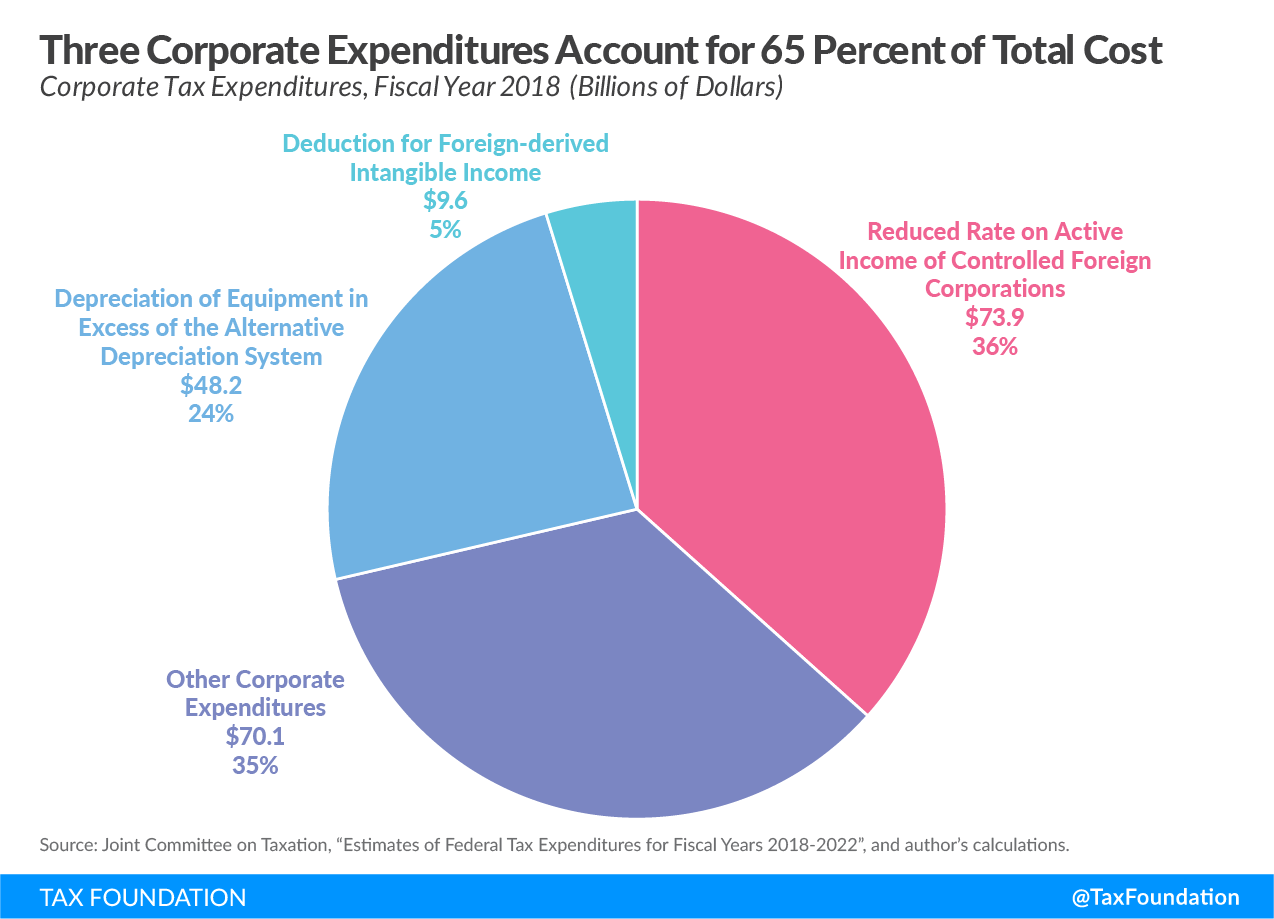

The three largest corporate tax expenditures, which make up approximately 65 percent of the total cost, illustrate the broad role some tax expenditures play:

Reduced Tax Rate on Active Income of Controlled Foreign Corporations ($73.9 billion)

Before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was passed, active foreign income was usually taxed upon repatriationRepatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the US tax code created major disincentives for US companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. . Now, global intangible low-tax income (GILTI) is taxed currently, even if it is not distributed. This expenditure provides a 50 percent deduction to U.S. corporations on their GILTI. Some active income is now excluded from tax, and distributions from active income are now not taxed upon repatriation. GILTI is a broad change to the tax code intended to reduce the incentive to shift corporate profits out of the U.S. by using intellectual property.

Depreciation of Equipment in Excess of the Alternative Depreciation System ($48.2 billion)

The costs of equipment and machinery are depreciated over time to match the reduction in economic value as equipment wears down and becomes obsolete. Depreciation of equipment ensures that net income from the property is measured appropriately each year. This expenditure provides accelerated deductions relative to economic depreciation.

While depreciation is a useful accounting concept, a better approach would be to allow full expensing, according to which the cost of an asset is deductible in the year that the money is actually spent. Expensing prevents a firm’s profits from being overstated in real terms.

Deduction for Foreign-derived Intangible Income Derived from Trade or Business Within the U.S. ($9.6 billion)

Income earned by U.S. corporations from foreign markets would typically be taxed at the full U.S. rate. This expenditure provides a deduction worth 37.5 percent of foreign-derived intangible income (FDII). Under GILTI and FDII, U.S.-based multinational companies face roughly the same tax rate on intangibles used in serving foreign markets regardless of where those intangibles are located. If intellectual property is located in a foreign market and is used to sell products to foreign customers, it faces a minimum tax rate of between 10.5 percent and 13.125 percent through GILTI. If that intellectual property is located in the U.S. and is used to sell products to those foreign customers, it faces a tax rate of 13.125 percent through FDII.

Together, FDII and GILTI are intended to serve as a carrot and stick encouraging companies to place profits and intellectual property in the U.S.

The tax code shouldn’t be full of provisions that unfairly reward some activities while punishing others, regardless of whether they’re directed towards individuals or corporations. Policymakers should scrutinize every expenditure, determine whether it fits with the principles of sound tax policy, and remember that not all expenditures are equal.

Note: This is part of our “Business in America” blog series

The Lowered Corporate Income Tax Rate Makes the U.S. More Competitive Abroad

Corporate and Pass-through Business Income and Returns Since 1980

Firm Variation by Employment and Taxes

2017 GDP and Employment by Industry

Pass-Through Businesses Q&A

State Corporate Income Taxes Increase Tax Burden on Corporate Profits

Marginal Tax Rates for Pass-through Businesses Vary by State

Taxes on Capital Income Are More Than Just the Corporate Income Tax

Depreciation Requires Businesses to Pay Tax on Income That Doesn’t Exist