Taxes, Fiscal Policy, and Inflation

Consumer prices rose by 7 percent in 2021, the highest annual rate of inflation since 1982. Where did this inflation come from and what might its impacts be? Tax and fiscal policy offer important clues.

5 min read

Consumer prices rose by 7 percent in 2021, the highest annual rate of inflation since 1982. Where did this inflation come from and what might its impacts be? Tax and fiscal policy offer important clues.

5 min read

While hoping for inflation’s continued decline, policymakers should finish the job and index the tax code to prepare for future bouts of high inflation and as a contingency in case it takes longer to defeat elevated inflation than expected.

4 min read

Inflation is often called a hidden tax, but in many states it yields a far more literal tax increase as tax brackets fail to adjust for changes in consumer purchasing power.

5 min read

The ongoing economic uncertainty from Russia’s war in Ukraine, economic recovery, supply chain disruptions, and rising interest rates have highlighted the importance of business investment.

30 min read

By implementing a more sophisticated and nuanced trigger system for its tax reduction goals, North Carolina can sustain its trajectory toward lower tax rates, reinforce its reputation as a business-friendly state, and ensure long-term fiscal stability in an ever-changing economic landscape.

4 min read

Without aligning fiscal discipline with pro-growth tax policies, Germany and the EU risk high deficits, mounting debt, and sustained inflation.

5 min read

With property tax bills on the rise, homeowners are searching for answers—and some even want to abolish the tax altogether. In this episode, we break down why property taxes are increasing, common but flawed solutions, and why the property tax remains an economically efficient revenue source.

The Tax Foundation uses and maintains a General Equilibrium Model, known as our Taxes and Growth (TAG) Model to simulate the effects of government tax and spending policies on the economy and on government revenues and budgets.

9 min read

While LIFO is rarely the main focus of the overall tax policy debate, it is a sound structural piece of the tax code. LIFO comes close to matching the economic ideal while still remaining true to the accounting principle.

15 min read

Rather than hurting foreign exporters, the economic evidence shows American firms and consumers were hardest hit by tariffs imposed during President Trump’s first-term.

5 min read

The French Revolution provides insight into the relationship between a government and its citizens and serves as a reminder that tax policy can have impacts (big and small) that last for centuries.

As Kansas policymakers consider ways to provide long-term property tax relief, a well-structured, exemption-free levy limit would be a structurally sound and effective reform to consider.

8 min read

Thirty-nine states will begin 2025 with notable tax changes, including nine states cutting individual income taxes. Recent years have seen a wave of significant tax reforms, and the changes scheduled for 2025 show that these efforts have not let up.

25 min read

President-elect Trump may want to impose tariffs to encourage investment and work, but his strategy will backfire. Tariffs will certainly create benefits for protected industries, but those benefits come at the expense of consumers and other industries throughout the economy.

5 min read

Policymakers can and should address taxpayers’ legitimate grievances about out-of-control property tax bills, but they should do so without upending a system of taxation that is more efficient, fair, and pro-growth, and better suited to municipal finance, than any of the alternatives.

39 min read

Explore the IRS inflation-adjusted 2025 tax brackets, for which taxpayers will file tax returns in early 2026.

4 min read

Allowing full deductibility of residential structures would mean more housing construction, particularly multifamily housing—a practical solution to address housing affordability challenges.

6 min read

Exempting Social Security benefits from income tax would increase the budget deficit by about $1.6 trillion over 10 years, accelerate the insolvency of the Social Security and Medicare trust funds, and create a new hole in the income tax without a sound policy rationale.

6 min read

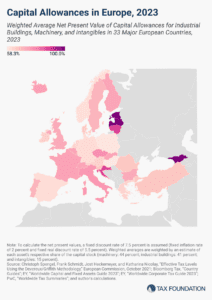

Although sometimes overlooked in discussions about corporate taxation, capital allowances play an important role in a country’s corporate tax base and can impact investment decisions—with far-reaching economic consequences.

4 min read

As members of Congress prepare to address the expiration of the TCJA, they should appreciate how revenues have evolved since 2017.

4 min read

The European Union’s experience with high inflation highlights the critical need for adaptive fiscal policies. Best practices drawn from the academic literature recommend implementing automatic adjustment mechanisms with a certain periodicity and based on price increases.

31 min read

Rather than adopt temporary policies that phase out and expire, policymakers should focus their efforts on long-term reforms to support investment.

6 min read

Lawmakers should see 2025 as an opportunity to consider more fundamental tax reforms. While the TCJA addressed some of the deficiencies of the tax code, it by no means addressed them all.

8 min read