Key Findings

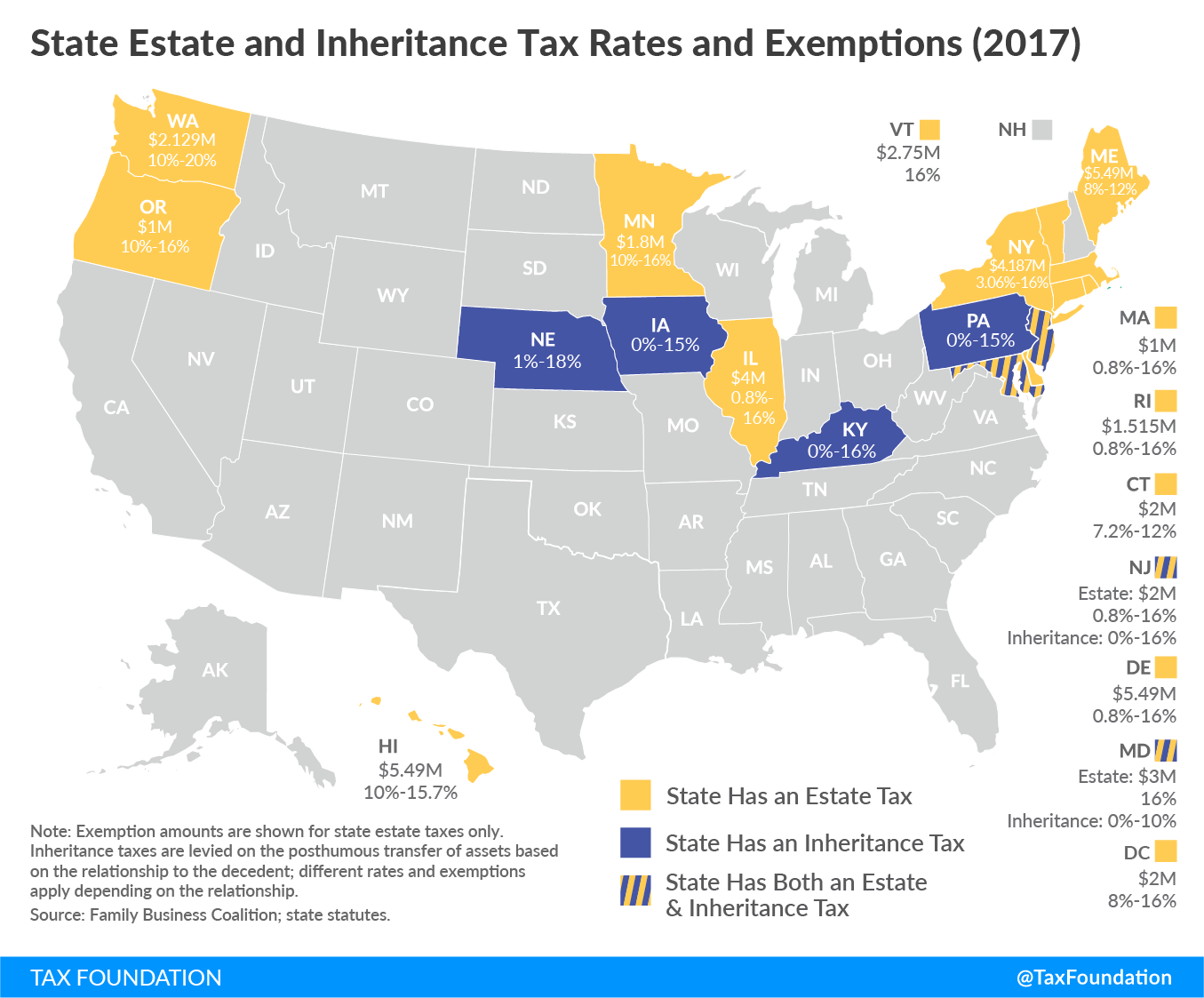

- Eighteen states and the District of Columbia impose either inheritance or estate taxes, with fourteen states (plus Washington, D.C.) levying estate taxes and six states levying inheritance taxes. Of these, two states (Maryland and New Jersey) impose both taxes, though New Jersey is in the process of repealing its estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. .

- For decades, the federal government offered a credit against federal estate taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. liability for state inheritance and estate taxes paid, which allowed states to impose a “pick-up” estate tax without increasing residents’ overall tax liability. The elimination of this credit in 2005 ushered in a new era of estate and inheritance taxAn inheritance tax is levied upon the value of inherited assets received by a beneficiary after a decedent’s death. Not to be confused with estate taxes, which are paid by the decedent’s estate based on the size of the total estate before assets are distributed, inheritance taxes are paid by the recipient or heir based on the value of the bequest received. competition among the states.

- Washington State has the highest top marginal estate tax rate at 20 percent, while the 18 percent rate Nebraska imposes on bequests to nonrelated individuals is the nation’s highest inheritance tax rate.

- State inheritance and estate taxes, together with the federal estate tax, reduce investment, discourage business expansion, and can sometimes drive wealthy taxpayers out of state.

- When high net worth individuals leave states with high inheritance and estate taxes, their state of origin loses not only the prospective estate or inheritance tax revenue, but also the revenue from other taxes that might have been collected during their lifetimes.

- Estate planning and tax avoidance strategies create dead-weight losses, reduce economic efficiency, and in some instances break up farms and family-owned businesses. These costs must be taken into account above and beyond actual collections under estate and inheritance tax regimes.

- Since 2005, states have been moving away from estate and inheritance taxes, a trend that is likely to continue.

Introduction

“Pray don’t be uneasy,” shouts the steward in one of Ivan Turgenev’s novellas, his voice carrying across the rising waves to a man in a boat, his little craft darting toward impending doom. “It’s of no consequence! It’s death! Good luck to you!”[1] But human beings have always treated death as a matter of the greatest consequence. They anticipate it, fear it, try to bargain with it, and seek to avoid it.

Not coincidentally, they exhibit much the same set of behaviors when it comes to taxes imposed at death, the estate and inheritance taxes many taxpayers revile about as much as the event itself—levies regarded as cruel as death, and hungry as the grave.[2]

Ben Franklin’s famous aphorism[3] conjoins death and taxes in a shared certitude, but frequently the primary fact of estate taxation is the existence of uncertainty. Death may be certain; its timing is not. Estate planning is complicated by this fundamental uncertainty, along with a constellation of ancillary ones, ranging from the volatility of markets to the liquidity of assets to changes in intended beneficiaries to the tax exposure of heirs. The multiplicity of state inheritance and estate tax regimes further complicates matters, though with competent planning and avoidance techniques, it is frequently possible to largely evade their sting.

State inheritance and estate taxes are a shadow of their former selves, but the shadow they cast—much like death itself—can become a preoccupation. Because they exist, economic opportunities are foregone, inferior investments are made, and capital migrates across state borders. Sometimes people, too.

This paper examines the various characteristics of state inheritance and estate taxes, sets out their current rates and structures, explores the history of estate and inheritance taxation in the United States, and reviews the economic literature on the effects of these taxes on economic activity, migration, and revenue. A thousand doors may lead to death,[4] but each one has different implications for the eighteen states (and the District of Columbia) with estate or inheritance taxes—and for their many peers, eager to exploit a competitive advantage.

Variations in the Structure of State Inheritance and Estate Taxes

Taxes can be imposed on the entirety of a decedent’s bequests (an estate tax) or on the receipt of an estate’s proceeds (an inheritance tax).[5] The differences are not merely semantic, and diverge in both their legal and economic incidence. Estate taxes are imposed on the net value of an estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the rate indicated by the total value of all taxable bequests and before any distribution to heirs. Inheritance taxes are paid by legatees based on their share of the inheritance and, often, their relationship with the deceased. Whereas estate taxes are paid by the decedent’s estate before assets are distributed to heirs, inheritance taxes are remitted by the recipient of a bequest. Both inheritance and estate taxes exempt transfers made to a spouse after death.

Whereas inheritance taxes once predominated, today estate taxes—following the federal approach—are more prevalent. Fourteen states and the District of Columbia impose estate taxes, while six states levy an inheritance tax. Of these, two states (Maryland and New Jersey) impose both estate and inheritance taxes, though New Jersey is in the process of repealing its estate tax. Taken together, eighteen states and Washington, D.C., impose an inheritance tax, an estate tax, or both.

Until recently, the federal government provided a credit against state inheritance and estate tax liability, up to a certain amount. Consequently, all fifty states adopted estate taxes designed, at the very least, to capture all revenue up to this threshold (commonly called the “pick-up tax”), since they could do so without increasing anyone’s tax liability. Although the credit has since been repealed and most states now forego estate taxes altogether, several states’ estate taxes still mirror the structure of the old pick-up taxes. A deduction now takes the place of the credit, but it is innately less generous and leaves taxpayers with additional liability should their state elect to impose an estate or inheritance tax.[6]

The federal estate tax features a “unified credit” which functionally wipes out liability under an exempted amount, currently set at $5.49 million and adjusted annually for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. . Technically this functions as a credit equal in value to liability for the first $5.49 million in estate value, with all estate value above that threshold taxed at the top marginal ratecurrently 40 percent.[7] (Lower federal estate tax rates still exist in statute, but are functionally irrelevant, since they only apply to estate values wiped out by the credit.) Some states match the federal level, while others adopt their own exemptions and exclusions, but at the state levels, the most common structure is an exemption of a given amount of estate value rather than a credit against liability.

State inheritance and estate taxes typically only apply to larger transfers of wealth, with an exemption for smaller estates and bequests. The nature and size of exemption can vary, however. Most commonly, only estate or inheritance amounts above a given threshold are subject to tax. Occasionally, however, a credit may be offered which effectively eliminates taxation of income below a certain amount, which is functionally the same, but has the implicit effect of eradicating the lower tax brackets.

Illinois, for instance, has twenty rates and brackets, beginning with 0.8 percent on the first $40,000 of taxable estate value. The state adopts a $4 million exclusion, however, so the first $4 million is untaxed, while the value of the estate from $4,000,000 to $4,040,000 is taxed at 0.8 percent, the lowest rate on the estate tax schedule. New Jersey also has a 0.8 percent rate, in this case on the first $100,000, but its $2 million exemption is accomplished through a tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. which wipes out liability under the state’s first eight brackets and part of the ninth. Accordingly, even though the state theoretically imposes a 0.8 percent rate, the first dollar of post-credit taxable estate value is taxed at a rate of 7.2 percent, which according to the rate schedule is imposed on estate value between $1.6 and $2.1 million.[8]

Other variations abound. Although New York offers a generous exemption, it taxes the entire value of estates that exceed it, not just the net of the exemption.

Inheritance taxes tend to have different rate schedules for distinct classes of heirs, with relatives receiving preferential treatment compared to nonrelated individuals, and direct lineal descendants sometimes exempted altogether. Transfers from decedents to surviving spouses are not subject to inheritance tax in any state. Unlike estate taxes, inheritance taxes tend not to feature substantial exemptions.

States also vary in the deductions they allow and the rules they use in determining fair market value for tax purposes. Most but not all states have adopted the Uniform Simultaneous Death Act, which provides that if two or more people die within a short time of each other due to the same accident, and no will exists, then assets are passed directly to relatives without first being transferred from one estate to the other. Some states conform to all federal deductions, while others adopt their own or none at all.[9]

Gift taxes are frequently envisioned as occupying a similar space as estate and inheritance taxes, even though they are imposed on transfers made during the grantor’s lifetime, because they foreclose a ready avenue of estate and inheritance tax avoidance for anyone willing to transfer income or assets before they die. Only one state imposes a stand-alone gift taxA gift tax is a tax on the transfer of property by a living individual, without payment or a valuable exchange in return. The donor, not the recipient of the gift, is typically liable for the tax. , while ten other states extend their inheritance and estate taxes to gifts made in contemplation of death, usually defined as gifts made within a few years of the date of death.[10] Since 1977, estate and gift taxes have operated as a unified tax at the federal level, with lifetime giving debited against the federal estate tax exemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax. .[11]

At the current federal estate tax rate of 40 percent on estate values above $5.49 million, the top combined marginal estate tax rate that can be experienced anywhere in the country is 60 percent in Washington State. New Jersey, with estate and inheritance taxes that each top out at 16 percent, can yield a combined top marginal rate (considering both types of taxes together) of 72 percent. Although they are responsible for a modest share of government revenue—about 0.6 percent of state and 0.7 percent of federal collections[12]—these necessarily loom large for affected families, and tend to encourage aggressive avoidance strategies.

A Short History of Estate and Inheritance Taxes in the United States

In 1797, the fledgling American government levied a quasi-estate tax to pay for a Quasi-War.[13] Structured as a stamp tax on the inventories, wills, and other documents of decedents, the tax raised little revenue and was abolished within a few years.[14] At the federal level, inheritance taxation retained its linkage to war for quite some time: an inheritance tax was imposed for eight years beginning in 1862 to help finance the Civil War, then reimposed in 1898 to cover costs incurred in the Spanish-American War.[15] The federal estate tax was first implemented in 1916, on the eve of the U.S. entry into World War I, but this time the tax took on a more permanent character,[16] perhaps because it came to be seen as a way to break up the concentrated wealth of the Gilded Age.[17]

For much of the 20th century, state inheritance and estate taxes were designed in conjunction with the federal estate tax, but they did not begin that way. Pennsylvania enacted the first such tax when it adopted a 2.5 percent inheritance tax on collateral heirs (those who are not direct descendants of the decedent) in 1826 to finance a proposed canal project designed to compete with New York’s Erie Canal. Two years later, Louisiana imposed a 10 percent inheritance tax, but restricted its application to nonresidents. California became the first state to apply an inheritance tax to direct as well as collateral heirs.[18]

State inheritance taxes only came into their own, however, with the enactment of New York’s tax on collateral heirs in 1885, which is often seen as a turning point in inheritance taxation. In the two years that followed, another twelve states had adopted inheritance taxes,[19] and by the time the federal government adopted an estate tax in 1916, forty-three states imposed some such tax.[20]

The early 20th century would prove to be the heyday of state inheritance (and, tenuously, estate) taxes; by the time a federal estate tax was adopted, state inheritance taxes were already losing ground as a share of state revenue. In 1907, they accounted for 8.4 percent of state revenue,[21] but states were already exploring new sources of revenue. From 1915 to 1924, annual state income tax collections increased fiftyfold, eclipsing inheritance and estate tax collections, which increased threefold over the period.[22]

As state inheritance and estate taxes became more onerous, the handful of states foregoing them gained a competitive advantage—one they were not afraid to exploit. By the early 1920s, capital flight to holdouts Florida and Alabama was a pressing concern, with Florida policymakers embracing the absence of an inheritance tax as a “lure” for wealthy retirees,[23] and the Alabama Power Company taking out advertisements boasting of the tax advantages of life in its home state: “Who Gets Your Estate When You Die? That All Depends on Where You Live … If the H. C. Frick estate had been in Alabama and the testator had been a resident of Alabama, his state inheritance tax would have been Nothing!”[24]

Initially seen as a threat to state inheritance taxes, the federal estate tax soon became the mechanism of their salvation. At a series of three national conferences, states with inheritance taxes grappled with ways to bring defector states in line. The result was the Delano Committee Report, produced under the guidance of Frederic A. Delano II,[25] uncle and mentor to future president Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Its proposed solution was straightforward: the federal government had to pick up the cost of state inheritance and estate taxation.

In fact, the federal government had already begun to do so. In 1924, the federal government began offering a federal credit for state inheritance and estate taxes, initially capped at 25 percent of the federal estate tax.[26] As this level was below the prevailing level of existing state taxes, the Delano Commission recommended raising the credit cap to 80 percent. The commission found an ally in Rep. William Green, chairman of the House Ways and Means CommitteeThe Committee on Ways and Means, more commonly referred to as the House Ways and Means Committee, is the chief tax-writing committee in the US. The House Ways and Means Committee has jurisdiction over all bills relating to taxes and other revenue generation, as well as spending programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance, among others. , who worried that “[i]sles of refuge would be created, not only by one state but by several.”[27]

“Let me say to the people of Florida that you never can make a really great State through colonies of tax dodgers or money grabbers, parasites and coupon cutters, jazz trippers and booze hunters,” he fulminated.[28] He shepherded through the requisite legislation, and by 1926, the generous new cap was in place. (The Senate briefly considered going in a different direction by repealing the estate tax entirely.[29])

The deal proved too enticing for even Florida to hold out,[30] and after a few years, only Nevada (which repealed its inheritance tax in 1925) elected to forego both inheritance and estate taxes.[31] Many states converted their old inheritance taxes into estate taxes after the federal model, and frequently set the rates with reference to the federal credit.[32] The resulting “pick-up taxes” were fully creditable against federal tax liability, thus their existence—and the revenue they generated for states—did not increase taxpayers’ overall liability. While some states continued to impose taxes above the “pick-up tax” threshold, rates increasingly converged on the federally covered amounts.[33] The effects of interstate competition had been blunted.

The next significant chapter in state inheritance and estate taxation opened in 2001, and once again, its impetus was federal legislation. The Economic Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA, sometimes called the first Bush tax cut) included a four-year phaseout of the credit for state inheritance and estate taxes among its provisions, replacing it with a far less generous tax deductionA tax deduction allows taxpayers to subtract certain deductible expenses and other items to reduce how much of their income is taxed, which reduces how much tax they owe. For individuals, some deductions are available to all taxpayers, while others are reserved only for taxpayers who itemize. For businesses, most business expenses are fully and immediately deductible in the year they occur, but others, particularly for capital investment and research and development (R&D), must be deducted over time. by 2005.[34]

In response to EGTRRA, some states repealed their estate and inheritance taxes. Others had statutorily tied their rates to the federal credit, so its elimination effectively zeroed out those states’ taxes even though they technically remained on the books. A smaller number of states decoupled from the federal law or adopted stand-alone estate taxes.[35] In 2001, every state levied taxes on estates or inheritances; today, the number stands at eighteen states and the District of Columbia.

Estate Tax Rates

Fourteen states and the District of Columbia impose estate taxes, with top rates ranging from 12 percent in Connecticut and Maine to 20 percent in Washington State. Five states use “zero brackets,” meaning that their exemption is built into their rate structure, with no tax assessed on an initial given amount of estate proceeds. (For instance, Minnesota’s lowest rate of 12 percent is assessed on proceeds between $2.1 and $5.1 million.) Most other states have exemptions, with rate schedules only applying to the value of the estate above the exemption threshold. Two states (New Jersey and Rhode Island) employ tax credits which offset all taxes owed up to a certain amount, essentially erasing certain brackets.

Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island have identical rate structures, with 20 rates and brackets beginning at 0.8 percent on estate proceeds beginning at $40,000 of taxable value and peaking at 16.0 percent of the taxable estate above $10,040,000. This is the now-anachronistic pick-up tax schedule: the rates at which states captured the maximum amount possible under the old credit for state inheritance and estate taxes under the federal estate tax without increasing the tax burden for state taxpayers. These states opted to retain the old structure even after the credit was repealed.

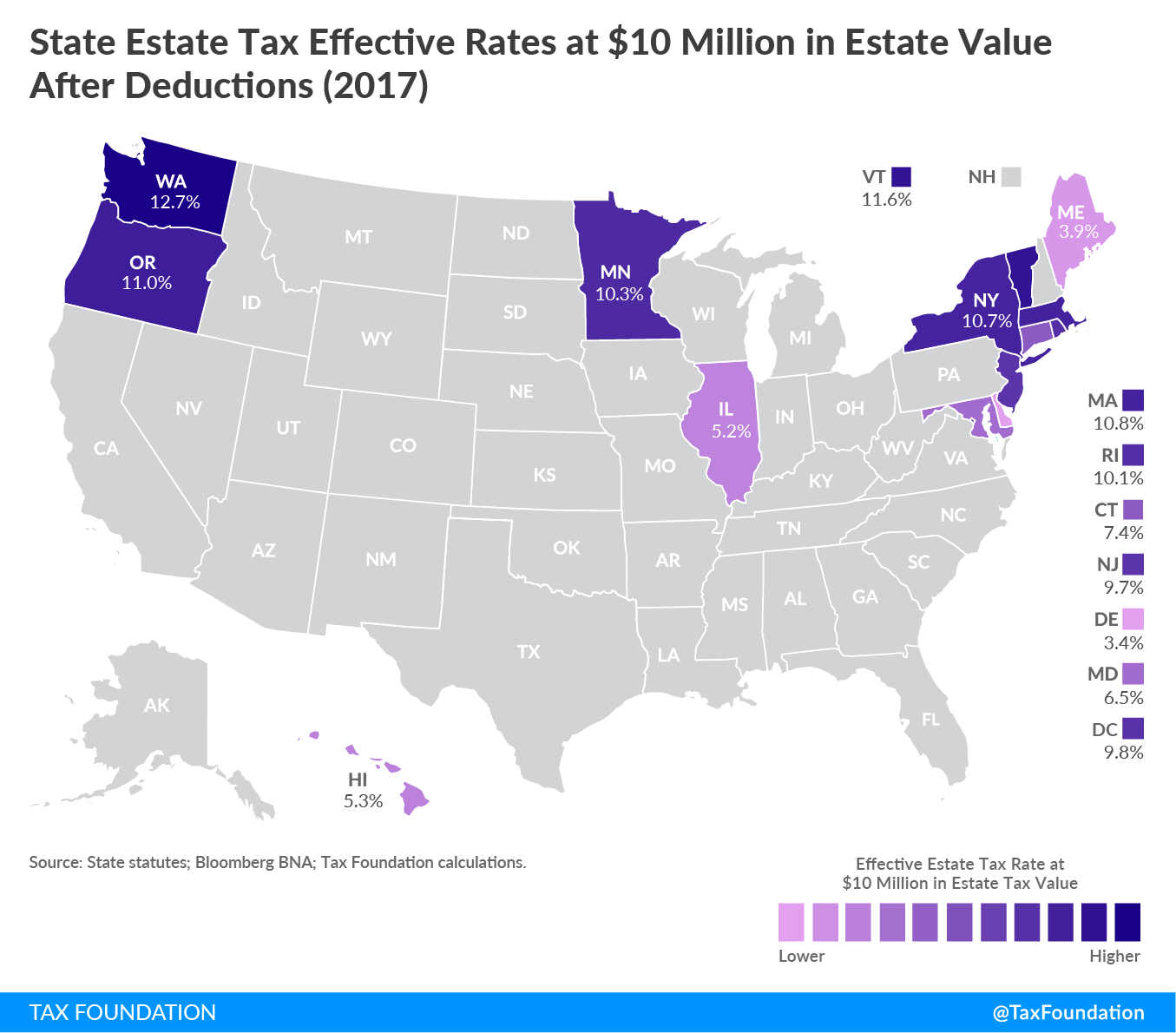

Due to the interactions of exemptions and rate schedules, estate tax treatment differs markedly across states and estate values. The following table shows effective rates across four estate values after deductions. Delaware and Maine consistently offer the lowest effective estate tax rates across estate values. Connecticut’s effective rates on estates valued at less than $5 million are above average, but its effective rates on larger estates are significantly below average. Vermont has perhaps the most progressive tax structure, though Washington State has the highest effective rates for the largest estates.

| Value of Estate After Deductions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | $2,500,000 | $5,000,000 | $10,000,000 | $20,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: State statutes; Bloomberg BNA; Tax Foundation calculations. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conn. | 1.4% | 4.6% | 7.4% | 9.7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| D.C. | 1.6% | 5.9% | 9.8% | 12.9% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Del. | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.4% | 9.0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hawaii | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.3% | 10.5% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Illinois | 0.0% | 0.7% | 5.2% | 10.2% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maine | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.9% | 7.8% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maryland | 0.0% | 2.1% | 6.5% | 11.0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass. | 5.7% | 8.0% | 10.8% | 13.4% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minn. | 1.9% | 7.0% | 10.3% | 13.2% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| N.J. | 1.6% | 5.8% | 9.7% | 12.8% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| N.Y. | 0.0% | 0.0% | 10.7% | 13.3% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ore. | 6.1% | 8.5% | 11.0% | 13.5% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R.I. | 3.1% | 6.7% | 10.1% | 13.1% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vt. | 0.0% | 7.2% | 11.6% | 13.8% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wash. | 2.2% | 7.4% | 12.7% | 16.3% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Connecticut

The Nutmeg State imposes a nine-bracket estate tax at rates ranging from 7.2 to 12.0 percent, with a $2 million “zero bracket”-style exemption. The top rate kicks in at $10.1 million.[36]

Delaware

The first state to ratify the U.S. Constitution is one of the last states to maintain an estate tax structure designed to take advantage of the old “pick-up tax” enabled by a credit against state estate taxes up to 80 percent of federal estate tax liability. Delaware also adopts the federal exemption level, which currently stands at $5.49 million, with amounts above the exemption subject to the twenty-bracket schedule, with rates ranging from 0.8 to 16.0 percent.[37]

Hawaii

The newest state also conforms to the federal exemption of $5.49 million, though it adopts its own rate structure, with rates ranging from 8.0 to 16.0 percent. The state has a sizable $1 million “zero bracket” in addition to the federal exemption, meaning that in practice, no tax is owed on the first $6.49 million in estate proceeds.[38]

Illinois

Illinois retains the old pick-up tax rate schedule with a statutorily-set $4 million exemption.[39]

Maine

Unique among states, Maine imposes a rate structure that corresponds to the federal exemption. The first bracket begins with the current amount of the federal exemption, with two successive brackets separated by $3 million each. This means that the three brackets currently begin at $5.49 million, $8.49 million, and $11.49 million respectively.[40]

Maryland

Maryland retains the old federally-indicated rate structure paired with a $3 million exemption.[41] Maryland also maintains an inheritance tax, and will be the only state to impose both an estate and inheritance tax once New Jersey finishes phasing out its estate tax (while maintaining its inheritance tax) in 2018.

Massachusetts

The Bay State’s estate tax system is unusually complex. It also follows the old federal pick-up tax-oriented rate structure, with a threshold—not an exemption—of $1 million. This means that on estates valued less than $1 million after deductions, no tax is owed, but for all others, tax must be remitted on the full amount, not just the amount over $1 million, creating a tax cliff. To further complicate matters, the amount owed is the lesser of (1) the Massachusetts estate tax schedule applied to the adjusted taxable estate or (2) federal estate tax liability under the Internal Revenue Code in effect on December 31, 2000, using the rate from the July 1999 revision and the unified credit intended for 2006 and after, and reduced by the unified credit.[42]

To illustrate, imagine an adjusted taxable estate of $1.1 million, all of which (not just the amount over $1 million) is subject to tax. Using the state’s rate schedules, this yields tax liability of $41,360. Federal estate tax liability for a similar estate would only be $41,000, despite a top applicable rate of 41 percent (based on the rates in effect in 2000), because of the unified credit, which acts like an exemption or exclusion. Therefore, Massachusetts liability would be reduced to $41,000. This provision, however, only benefits estates valued at just slightly above $1 million.

Minnesota

Minnesota employs a “zero bracket” to exempt estates under $2.1 million, after which it imposes a six-bracket estate tax with a top rate of 16.0 percent.[43] The state is currently phasing in an increase in the exemption, ultimately scheduled to reach $3 million in 2020.[44]

New Jersey

In lieu of a traditional exemption, New Jersey offers a credit which eliminates liability against the first $2 million in estate value. This means that, instead of the remainder of the estate’s value being subjected to the entire rate schedule beginning with the lowest rate, the first dollar above $2 million is taxed at the 7.2 percent rate on estate value between $1.6 and $2.1 million.[45] The New Jersey estate tax is scheduled for repeal in 2018, though the state’s inheritance tax will remain.

New York

New York’s tax does not apply to estates valued at less than $5.125 million after applicable deductions, but this is a threshold, not an exemption, yielding an unusually sizable tax cliff. An estate valued in excess of that figure is taxed on the entire value of the estate, not just the amount above $5.125 million.[46] Accordingly, there is an exceedingly strong incentive for those with estates only modestly above the threshold to pursue planning strategies which bring it below that point.

Oregon

Subsequent to a “zero bracket” exempting the first $1 million, Oregon’s lowest estate tax bracket is taxed at a rate of 10 percent, yielding the nation’s highest effective rates on the first few million dollars of taxable estate.[47]

Rhode Island

Rhode Island’s rate and bracket structure is still designed around the old “pick-up tax” model, but the state’s reliance on a credit, rather than an exemption, follows only New Jersey. The credit, which is inflation-adjusted, is currently valued at $65,370, which effectively exempts the first $1,515,156 in estate value from taxation.[48]

Vermont

The nation’s only flat-rate estate tax is levied by Vermont, which imposes a 16 percent rate on all estate proceeds above a “zero bracket” of $2.75 million.[49]

Washington

The Evergreen State imposes the highest top marginal estate tax rate in the nation, imposing a 20 percent rate on taxable estate values above $9 million. The state has an inflation-adjusted exemption which currently stands at $2.129 million.[50]

District of Columbia

As part of a broader tax reform package, the District of Columbia is gradually increasing its “zero bracket”-style exemption to match the value of the federal unified credit. The top rate is 16 percent.[51]

| State | Tax Rate | Exemption | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * Exemption in the form of a “zero bracket.” † New Jersey and Rhode Island utilize credits; values converted to exemption amounts. ‡ New York taxes the entirety of net estate value for estates exceeding threshold. Sources: State statutes; Bloomberg BNA. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conn. | 0.0% | > | $0 | $2,000,000* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7.2% | > | $2,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7.8% | > | $3,600,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.4% | > | $4,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.0% | > | $5,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.6% | > | $6,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.2% | > | $7,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.8% | > | $8,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.4% | > | $9,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $10,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Del. | 0.0% | > | $0 | $5,490,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.8% | > | $40,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.6% | > | $90,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.4% | > | $140,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3.2% | > | $240,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.0% | > | $440,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.8% | > | $640,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5.6% | > | $840,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6.4% | > | $1,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7.2% | > | $1,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.0% | > | $2,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.8% | > | $2,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.6% | > | $3,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.4% | > | $3,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.2% | > | $4,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $5,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.8% | > | $6,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.6% | > | $7,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.4% | > | $8,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.2% | > | $9,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $10,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| D.C. | 0.0% | > | $0 | $2,000,000* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.0% | > | $2,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.8% | > | $2,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.6% | > | $3,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.4% | > | $3,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.2% | > | $4,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $5,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.8% | > | $6,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.6% | > | $7,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.4% | > | $8,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.2% | > | $9,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $10,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hawaii | 10.0% | > | $0 | $5,490,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.0% | > | $1,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $2,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.0% | > | $3,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.0% | > | $4,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.7% | > | $5,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Illinois | 0.0% | > | $0 | $4,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.8% | > | $40,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.6% | > | $90,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.4% | > | $140,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3.2% | > | $240,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.0% | > | $440,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.8% | > | $640,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5.6% | > | $840,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6.4% | > | $1,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7.2% | > | $1,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.0% | > | $2,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.8% | > | $2,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.6% | > | $3,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.4% | > | $3,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.2% | > | $4,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $5,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.8% | > | $6,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.6% | > | $7,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.4% | > | $8,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.2% | > | $9,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $10,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maine | 0.0% | > | $0 | $5,490,000* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.0% | > | $5,490,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.0% | > | $8,490,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $11,490,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maryland | 0.0% | > | $0 | $3,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.8% | > | $40,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.6% | > | $90,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.4% | > | $140,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3.2% | > | $240,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.0% | > | $440,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.8% | > | $640,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5.6% | > | $840,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6.4% | > | $1,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7.2% | > | $1,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.0% | > | $2,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.8% | > | $2,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.6% | > | $3,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.4% | > | $3,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.2% | > | $4,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $5,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.8% | > | $6,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.6% | > | $7,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.4% | > | $8,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.2% | > | $9,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $10,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass. | 0.0% | > | $0 | $1,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.8% | > | $40,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.6% | > | $90,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.4% | > | $140,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3.2% | > | $240,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.0% | > | $440,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.8% | > | $640,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5.6% | > | $840,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6.4% | > | $1,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7.2% | > | $1,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.0% | > | $2,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.8% | > | $2,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.6% | > | $3,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.4% | > | $3,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.2% | > | $4,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $5,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.8% | > | $6,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.6% | > | $7,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.4% | > | $8,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.2% | > | $9,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $10,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minn. | 0.0% | > | $0 | $2,100,000* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $2,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.8% | > | $5,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.6% | > | $7,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.4% | > | $8,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.2% | > | $9,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $10,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| N.J. | 0.0% | > | $0 | $2,000,000† | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.8% | > | $100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.6% | > | $150,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.4% | > | $200,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3.2% | > | $300,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.0% | > | $500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.8% | > | $700,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5.6% | > | $900,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6.4% | > | $1,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7.2% | > | $1,600,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.0% | > | $2,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.8% | > | $2,600,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.6% | > | $3,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.4% | > | $3,600,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.2% | > | $4,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $5,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.8% | > | $6,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.6% | > | $7,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.4% | > | $8,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.2% | > | $9,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $10,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| N.Y. | 3.06% | > | $0 | $5,125,000‡ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5.0% | > | $500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5.5% | > | $1,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6.5% | > | $1,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.0% | > | $2,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.8% | > | $2,600,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.6% | > | $3,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.4% | > | $3,600,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.2% | > | $4,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $5,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.8% | > | $6,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.6% | > | $7,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.4% | > | $8,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.2% | > | $9,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $1,082,800 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ore. | 0.0% | > | $0 | $1,000,000* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.0% | > | $1,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.3% | > | $1,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.5% | > | $2,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.0% | > | $3,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.5% | > | $4,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $5,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.0% | > | $6,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.0% | > | $7,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.0% | > | $8,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $9,500,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R.I. | 0.0% | > | $0 | $1,515,156† | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.8% | > | $40,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.6% | > | $90,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.4% | > | $140,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3.2% | > | $240,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.0% | > | $440,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.8% | > | $640,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5.6% | > | $840,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6.4% | > | $1,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7.2% | > | $1,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.0% | > | $2,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.8% | > | $2,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.6% | > | $3,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.4% | > | $3,540,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.2% | > | $4,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.0% | > | $5,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.8% | > | $6,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.6% | > | $7,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.4% | > | $8,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.2% | > | $9,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $10,040,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vt. | 0.0% | > | $0 | $2,750,000* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $2,750,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wash. | 10.0% | > | $0 | $2,129,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.0% | > | $1,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.0% | > | $2,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16.0% | > | $3,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18.0% | > | $4,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19.0% | > | $6,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19.5% | > | $7,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20.0% | > | $9,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

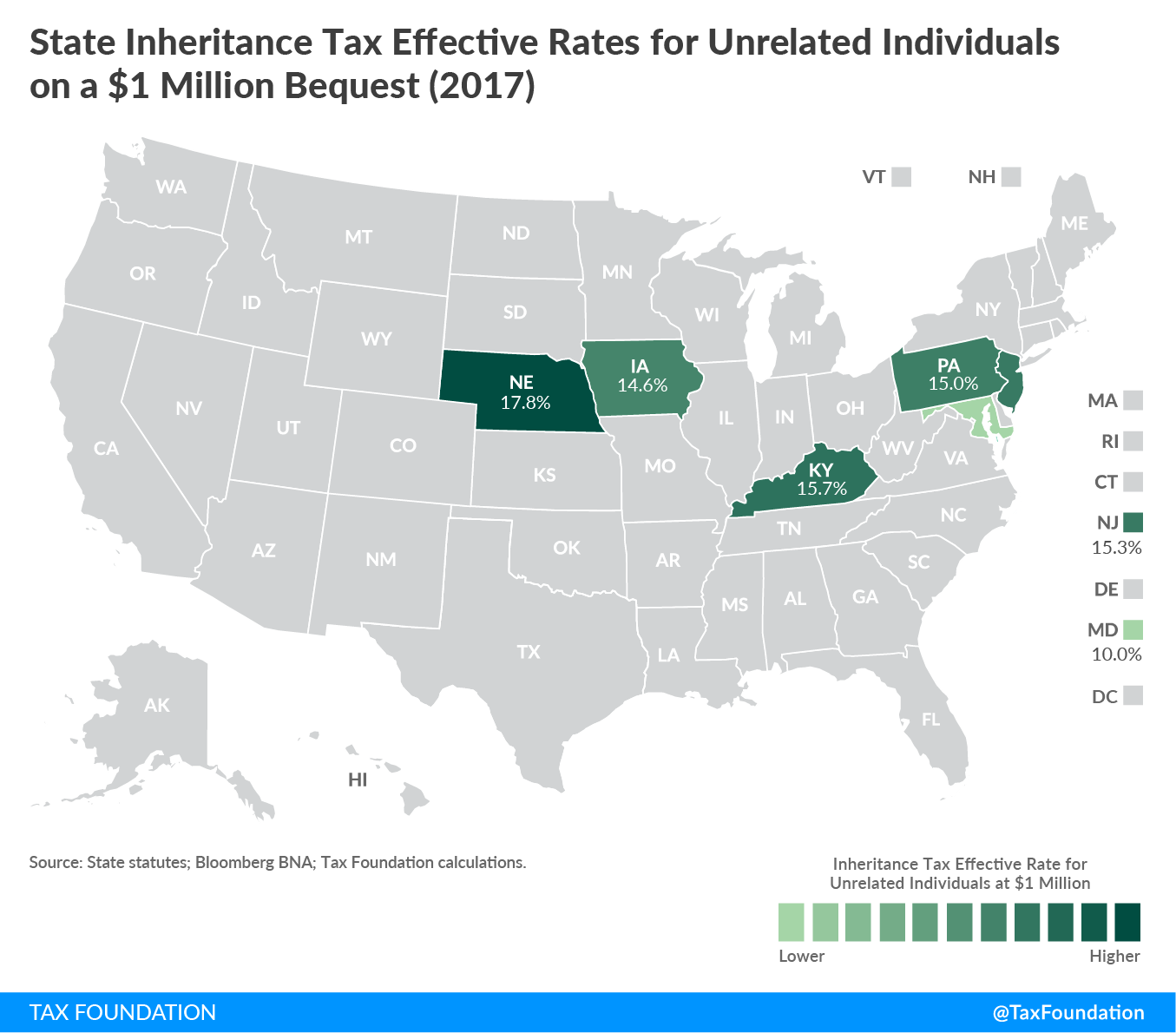

Inheritance Tax Rates

Six states impose inheritance taxes, two of which (Maryland and New Jersey) also levy estate taxes. Four states exempt lineal heirs (e.g., parents, children, and grandchildren), while the other two tax them, but at preferential rates. Nebraska imposes the nation’s highest top marginal inheritance tax rate, at 18 percent on nonrelated individuals.

Although states impose inheritance taxes on a variety of classes of heirs, the following table compares effective tax rates across three common categories: lineal heirs, other relations, and nonrelated heirs.[52]

| Lineal Heir | Other Related Individual | Nonrelated Individual | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | $100K | $500K | $1M | $100K | $500K | $1M | $100K | $500K | $1M | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: State statutes; Bloomberg BNA; Tax Foundation calculations. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iowa | 6.9% | 9.3% | 9.6% | 6.9% | 9.3% | 9.6% | 11.0% | 14.2% | 14.6% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ky. | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 9.0% | 14.2% | 13.5% | 12.7% | 15.3% | 15.7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Md. | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| N.J. | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 11.1% | 12.6% | 12.8% | 15.0% | 15.0% | 15.3% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nebr. | 0.6% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 8.3% | 10.5% | 10.5% | 16.2% | 17.6% | 17.8% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pa. | 4.5% | 4.5% | 4.5% | 15.0% | 15.0% | 15.0% | 15.0% | 15.0% | 15.0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Iowa

The Iowa inheritance tax is the nation’s most complicated, with different rate schedules for related individuals (other than lineal heirs, who are exempted), nonrelated individuals, charitable organizations, for-profit organizations, and unknown heirs. The state’s top rate (15 percent) applies to nonrelated individuals and for-profit organizations.[53]

Kentucky

Kentucky uses traditional inheritance classes, exempting lineal heirs (Class A) and subjecting other family members (Class B) and nonrelated individuals (Class C) and all others to different rate schedules.[54]

Maryland

Maryland levies a flat-rate inheritance tax, at 10 percent on all beneficiaries other than lineal heirs. The state also imposes an estate tax.[55]

Nebraska

The Cornhusker State adopts distinct flat rates (neglecting modest “zero brackets”) across several legatee classes, taxing lineal heirs at a low 1 percent rate while subjecting nonrelated individuals to an 18 percent rate.[56]

New Jersey

New Jersey’s $1.7 million kick-in of the top marginal rate for nonrelated individuals is by far the highest kick-in of any top marginal inheritance tax rate in the country. The state is in the process of repealing its estate tax, but the inheritance tax will remain.[57]

Pennsylvania

The Keystone State has the nation’s oldest inheritance tax, which is currently imposed at separate flat rates on lineal heirs, siblings, and all others.[58]

| State | Heir Class | Tax Rate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sources: State statutes; Bloomberg BNA. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iowa | Lineal Heirs | 0% | > | $0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related Individuals | 5% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6% | > | $12,500 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7% | > | $25,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8% | > | $75,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9% | > | $100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10% | > | $150,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nonrelated Individuals | 10% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12% | > | $50,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15% | > | $100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Charitable Bequests | 10% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| For-Profit Organizations | 15% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unknown Heirs | 5% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ky. | Class A Beneficiaries | 0% | > | $0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class B Beneficiaries | 0% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4% | > | $1,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5% | > | $10,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6% | > | $20,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8% | > | $30,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10% | > | $45,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12% | > | $60,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14% | > | $100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16% | > | $200,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class C Beneficiaries | 0% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6% | > | $500 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8% | > | $10,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10% | > | $20,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12% | > | $30,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14% | > | $45,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16% | > | $60,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Md. | Lineal Heirs | 0% | > | $0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| All Others | 10% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nebr. | Related Individuals | 0% | > | $0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1% | > | $40,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Remote Relatives | 0% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13% | > | $15,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nonrelated Individuals | 0% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18% | > | $10,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Charitable Bequests | 0% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| N.J. | Lineal Heirs | 0% | > | $0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other Related Individuals | 0% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11% | > | $25,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13% | > | $1,100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14% | > | $1,400,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16% | > | $1,700,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| All Others | 15% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16% | > | $700,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pa. | Lineal Heirs | 4.5% | > | $0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Siblings | 12% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| All Others | 15% | > | $0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Estate and Inheritance Tax Avoidance

Amounts remitted under estate and inheritance taxes represent only a portion of their cost. Many individuals who expect to leave sizable legacies employ sophisticated estate planning techniques to limit future liability. These avoidance strategies impose their own costs, both in terms of time and resources spent on estate planning and in economic opportunities foregone to reduce future tax exposure. These costs can be substantial, and they are economically inefficient, as they reduce wealth without increasing government revenues.

Many tax-avoidance activities are occasioned by the federal estate tax and would exist even absent state inheritance and estate taxes, though state levies may affect which planning techniques are economically viable. Some, however, are driven largely or exclusively by state inheritance and estate taxes, and can occasion migration to states which forego such taxes. If states lose older taxpayers due to looming estate and inheritance taxes, they would miss out on other tax revenue from those individuals as well. Evidences for estate and inheritance tax-related migration will be considered separately.

It is frequently argued that routine estate-planning techniques enable wealthy individuals to make sizable transfers while paying little or no tax,[59] and critics of estate and inheritance taxes have disparaged them as less taxes than “penalties imposed on those who retain unskilled estate planners.”[60] Some scholars have estimated that compliance costs may approach revenue yield,[61] with George Cooper writing for the Brookings Institution that “because estate tax avoidance is such a successful and yet wasteful process, one suspects that the present estate and gift tax serves no purpose other than to give reassurance to the millions of unwealthy that entrenched wealth is being attacked.”[62] Other experts have disputed these estimates,[63] but there can be no doubt that estate and inheritance taxes create deadweight losses and cause higher-tax states to lose out on revenue from other taxes by driving away wealthy seniors.[64]

Estate and inheritance tax planning activities can be classed under four headers: making tax-advantaged gifts and transfers, shifting assets and investments, exploiting tax valuation provisions, and hedging against future expenses. Most wealthy individuals engage in some combination of these practices, all of which impose their own costs. Each of these will be taken in turn.

1. Tax-advantaged gifts and transfers.

Gifts and transfers come in a variety of forms. Charitable contributions are tax-exempt and reduce the value of the estate, whether made during a person’s lifetime (inter vivos) or as a bequest,[65] where they can be taken as a deduction against the taxable value of the estate.[66] At the federal level, inter vivos transfers to others, including children, are tax-exempt up to an annual exclusion amount (currently $14,000).

There is also a lifetime exclusion, which tracks with—and reduces the threshold of—the federal estate tax exemption.[67] Several states tax gifts under their estate tax if made “in anticipation of death” (generally defined as having been made within a few years of death), but only Connecticut still imposes a stand-alone gift tax, which tracks the federal annual exclusion amount with a lifetime cap of $2 million.[68]

Even though inter vivos gifts reduce the estate tax exemption, they are still attractive compared to bequests at death,[69] as they are assessed on a tax-exclusive basis, while bequests are assessed on a tax-inclusive basis. A countervailing consideration, however, is that bequests are taxed on stepped-up basis (that is, the “basis” for an asset is set at current value, resetting the value for capital gains taxation), whereas gifts are not.[70]

2. Shifting assets and investments.

Assets and investments can be shifted for tax planning purposes. To avoid liquidity concerns or reduce future tax liability, one might arrange for the purchase of one’s business subsequent to death; shift wealth into tax-advantaged vehicles; or bring children on as owners of a home or co-investors in a business, allowing subsequent profits to accrue directly to an intended heir.[71] More sophisticated tax avoidance techniques include stock recapitalization and installment sales, though these methods have been rendered less effective by sundry reforms to the federal estate tax.[72]

That these asset allocations are precipitated by tax strategies suggests that they involve efficiency losses—that they are shifts away from investments deemed more lucrative. These transfers may also involve a loss of control that might otherwise be undesirable. While an aging parent may wish a child to take ownership of their home after their death, or hope that they will continue to run family business, they may not wish to cede that control during their lifetime absent the incentives created by estate and inheritance taxes. By reducing the value of marginal increases in wealth, such taxes may also induce wealthy individuals to earn or save less.[73]

3. Exploiting tax valuation provisions.

Family-owned farms and small businesses are permitted to reduce the assessed value of their real estate for estate tax purposes if the heirs maintain it as a family-owned operation for at least ten years.[74] This, of course, limits the future value of the bequest by constraining its possible uses. Astute estate planners can find other ways to obtain more favorable valuations as well, particularly regarding closely held corporations where valuations are inherently uncertain,[75] particularly if there is a lack of marketability.[76]

4. Hedging against future expenses.

One common criticism of estate and inheritance taxes is that inheritors of illiquid assets—like a business or farm—may have to liquidate the operation to pay the taxes. Although certain policy developments over the years have sought to ameliorate this concern, and federal estate tax liability can be paid on an installment basis,[77] individuals concerned about the ability of heirs to make estate tax payments may frequently take out life insurance[78] and maintain a high proportion of liquid assets to meet these burdens.[79]

A study by the Joint Economic Committee, a standing joint committee of Congress, concluded that “by affording so many tax avoidance options, the estate tax encourages owners of capital to shift resources from their most productive uses into less efficient (though more tax-friendly) uses.”[80] Avoidance techniques are costly and often sophisticated, but given that estate and gift taxes chiefly fall on wealthier taxpayers, it is reasonable to expect most potential payors to have access to tax planning resources,[81] even if they do not always implement successful strategies.

These estate planning techniques have real-world costs. Since tax liability at death is at least partially an artifact of poor estate planning or differing circumstances which do not necessarily indicate actual disparities of wealth, similarly-situated families can face vastly different tax burdens.[82] The costs of inheritance and state tax avoidance also extend far beyond the event itself, given that the timing of one’s passing is inherently uncertain.

Not only does this encourage otherwise inefficient resource allocation beginning what could be many years before death, but it also suggests that a miscalculation of one’s longevity can be the undoing of an otherwise intelligent estate plan.[83] Even those with clear exposure to estate and inheritance taxes, moreover, may fail to take obvious steps to mitigate liability, whether this is an expression of time preference, indifference, procrastination, or lack of knowledge. At the same time, many people deemed unaffected by the estate tax because their death incurred no liability may have spent considerable sums avoiding it.

Economic Ramifications

Studies show that economic decision-making is, in fact, affected by inheritance and estate tax regimes. This is consistent with the expectations of those likely to be affected by these taxes, which can drive costs in their own right, above and beyond actual tax liability. The process can be cumbersome, confusing, and time-consuming as well.[84]

A 1995 survey of owners of family businesses found that an average of 167 hours and $33,137 (over $55,000 in 2017 dollars) was spent planning for estate taxes. Sixty percent of respondents also claimed that if estate taxes were eliminated, they would immediately hire new employees (42 percent said they would hire 10 or more workers).[85] Among respondents with closely-held businesses worth more than $10 million, 67 percent felt that paying estate taxes would limit growth, and 41 percent feared that estate tax burdens would require selling all or part of the business, a view also held by 33 percent of respondents across businesses of all sizes.[86]

These self-reported estimates must be taken with a grain of salt, but strongly suggest that small, family-owned businesses adjust their decisions based on the existence of estate and inheritance taxes. The conclusion of one of the scholars who conducted the survey was stark: “The results strongly indicate that the modest revenue received from the tax is not worth its cost. The tax is apparently counterproductive, significantly limiting economic growth, development and job creation.”[87]

Historically, owners of family-owned farms and small businesses have been particularly opposed to the estate tax, frequently citing the concern that the tax would require the farm or business to be broken up to afford the liability. Examples of this transpiring are relatively rare,[88] which has led some critics to dismiss the concern, but there is good reason to believe that this reflects conscious—and often costly—economic planning on the part of potentially affected individuals.[89] A significant amount of estate planning is driven by the simple and unavoidable fact that, unlike income taxes, estate and inheritance taxes pertain to capital values rather than income flows.[90]