Download Appendix PDF Download Report PDF

Key Findings

- TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reform is long overdue in Nevada, but public finance scholars uniformly agree that gross receipts taxes like those in Texas and Washington are among the most economically destructive forms of generating tax revenue.

- Nevada policymakers are considering a proposal to convert the existing flat $200 Business License Fee into a tiered system of 67 revenue ranges for each of 27 industry categories. Additionally, foreign filers and non-employer businesses would pay a flat fee of $400, bringing the total to 29 categories of filers and 1,811 possible flat-dollar-amount tax liabilities.

- The proposal is targeted to generate $250 million per year once fully implemented and is projected to raise $438 million over the first biennium. However, these revenue estimates may be overstated by hundreds of millions of dollars.

- While attempting to mitigate the inherent flaws of gross receipts taxes, the designers of the BLF created a complex tax structure that violates the principles of simplicity and neutrality. The proposal requires significant additional administration costs and compliance burdens, and a quick implementation invites disaster.

- BLF rates are arbitrarily calculated using Texas data from a single year, despite the high likelihood that such data is not representative of Nevada’s economy. BLF rates do not correlate with profitability, resulting in punitive taxes for some and taxation of unprofitable firms.

- The BLF designers incorporated revenue cliffs that result in absurdly high marginal tax rates, reaching over 13 million percent. BLF designers concede pyramiding will be a problem, violating the principle of neutrality.

- BLF industry categories were arbitrarily selected and will result in tax arbitrage and economic distortions, as seen in states with similar taxes.

- Texas and Washington, while providing the model for the Nevada BLF proposal, are considering proposals to repeal their analogous taxes.

- The BLF proposal violates the principle of transparency by mislabeling an obvious tax.

- The BLF as proposed likely violates the interstate commerce clause and federal law.

Executive Summary

Nevada policymakers are currently considering a proposed restructuring of the state’s Business License Fee (BLF), converting it from an annual, flat $200-per-business fee into a tiered system of tax liabilities based on business type and business revenue, paid quarterly. The proposal, developed primarily by Nevada economic analyst Jeremy Aguero, sets charges for 67 separate revenue ranges in each of 27 industry categories, plus a flat fee for foreign filers and non-employer businesses. The proposal is projected to raise $438 million in additional revenue over the biennium, primarily to fund Governor Brian Sandoval (R)’s proposed expansion of education spending.

Governor Sandoval has initiated an important conversation about tax reform, and he has expressed a willingness to consider alternative plans and to entertain a discussion about the merits and drawbacks of each. It is in the spirit of the constructive dialogue which the Governor has commenced that we offer these critiques of the proposed BLF restructuring.

Revenue-based business taxes in Ohio, Texas, and Washington state were the inspiration for the Nevada BLF proposal, according to proponents. Each of these taxes are unique in their own way but fall in the broad category generally known to public finance scholars as gross receipts taxA gross receipts tax, also known as a turnover tax, is applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like costs of goods sold and compensation. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and apply to business-to-business transactions in addition to final consumer purchases, leading to tax pyramiding. es. Gross receipts taxes were once a popular form of taxation across the world and among the states but have declined sharply over time due to their “haphazard pattern of effective tax rates across business inputs, which inefficiently distorts firm decisions regarding input choices,” their inherent “tax bias toward vertical integration … and against small firms,” and their “enormous and undesirable distortions.” Notwithstanding the Nevada proposal, the historical trend is toward repeal, with recent eliminations of similar taxes on gross receipts in Indiana (2002), New Jersey (2006), Kentucky (2006), and Michigan (2011).

Proponents also state that the BLF satisfies their goal of levying a simple, fair, and broad tax. While the BLF proposal is broad (the graduated structure will apply to approximately 47,000 businesses), it is neither simple nor fair. It will be Nevada’s most complex tax for both taxpayers and tax administrators, with a multi-step method of rate calculation bordering on arbitrary, 67 rates plus cliffs and phase-ins for each one, and unclear guidance for multi-industry and interstate companies. It is also decidedly non-neutral, with stated tax rates deliberately varying widely by industry such that it exacerbates tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action. and likely violates federal prohibitions against discriminatory taxation. Additionally, because fees defray the cost of providing a particularized benefit while taxes generate revenue for general purposes, the proposal is properly characterized as a tax, not a fee.

“Contrary to expectations of quick implementation, the BLF will likely require a long lead time of rule-writing and data-gathering before revenue can be collected. Ohio took seven years to phase in its Commercial Activities Tax, Texas took three years to begin collecting its Margin Tax (and collections were off the estimate by one-third even with the long lead time),[2] and Washington state has modified its Business & Occupation Tax almost constantly over its 80-year existence. Lessons learned from these states about going slowly and writing clear rules were not incorporated into the BLF proposal. Furthermore, the BLF proposal’s designers reject the likelihood of non-payroll businesses currently domiciled in Nevada choosing to relocate to other states rather than pay a greater BLF, which would mean the revenue estimate is significantly overstated (by as much as $100 million per year).

Tax reform is long overdue for Nevada.[3] But creating sound tax policy is more than a question of how much revenue is being raised and whether that amount is too much or not enough. Public finance experts and economists generally agree that not all taxes are created equal, and certain types of taxes are more damaging to the economy than others. Gross receipts taxes are uniformly considered to be among the worst of these. With four states recently repealing taxes resembling the BLF proposal and three others (Ohio, Texas, and Washington state) seriously considering proposals to reduce or eliminate theirs, Nevada should be careful about establishing a complex, arbitrary tax structure that will harm long-term economic development and growth.

The Proposed BLF Significantly Transforms the Existing BLF

The current BLF is paid by “all persons conducting business in Nevada with or without a location or employees” with the following exemptions: “nonprofit religious, charitable, or educational associations and governmental entities; a person who operates an in-home business, which generates less than 66-2/3% of the average annual wage; or a business that creates or produces motion pictures.”[4] The restructured BLF would use the existing business license fee structure, although administration would transfer from the Secretary of State to the Department of Revenue. Only companies with employees and situs in Nevada would be subject to the graduated-rate gross receipts structure; non-employers and foreign firms would pay a flat $400.

Total revenue is “broadly defined to include most types of business receipts from the sale of goods or revenue realized in the performance of a service”[5] – that is, gross receipts.

Several items would be excluded from the taxable revenue, including interest (other than installment sales), dividends, capital gains, wages reported on a W-2, gifts, casino revenues subject to the Gaming Win Percentage Fee, and other revenue subject to existing taxes, like the Net Proceeds of Minerals Tax.

Other Options Were Rejected Based on the Flawed Premise that the BLF Can Be Quickly Implemented and Would Be Broader than an MBT Fix

Economic analyst Jeremy Aguero explained the process that led to the BLF proposal in legislative testimony in March 2015.[6] He said that an individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. was rejected due to constitutional limitations and as a political non-starter, a traditional corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. was rejected due to the likely volatility in its collections, and a sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. on services was rejected due to the lead time it would take to implement. Aguero also said that they considered the existing Modified Business Tax (MBT), a simple and stable tax on business payroll, but concluded that it is presently not broad enough after legislative changes in 2011 narrowed its base from 100 percent of Nevada employers to 26 percent.[7] However, the restructured BLF, with receipts-dependent graduated rates, would apply to roughly the same number of businesses as the original, more broad-based MBT did (see Table 1).[8]

Table 1: Number of Businesses Paying Nevada Business Taxes |

|||

|

Original Broad MBT Structure |

Current MBT and BLF Structure |

Proposed Graduated-Rate BLF Structure |

|

|

Nevada Businesses with Payroll (47,146) |

100% of employers pay MBT (this represents approximately 18% of all businesses) Flat MBT rate on all businesses 100% pay flat $100 per year (until 2009) |

26% of employers currently pay MBT (this represents approximately 5% of all businesses) 2005: flat 0.63% 2007: graduated rate of 0.5% up to exemption, 1.17% above that 2011: flat 1.17% above exemption 100% pay flat $200 per year (after 2009) |

All businesses with more than $125,000 in Nevada gross revenue will pay the graduated-rate BLF (likely representing approximately 18% of all businesses) MBT structure continues as currently |

|

Nevada Businesses without Payroll (approx. 210,000) |

100% pay flat $100 per year (until 2009) |

100% pay flat $200 per year (after 2009) |

100% pay flat $400 per year |

|

Source: Tax Foundation review of SB 252 and compilation of Fiscal Analysis Division data (see Note 1). |

Rather than broadening the MBT to address the problems created by prior base-narrowing policy decisions, Aguero and his team looked to revenue-based business taxes in Ohio (Commercial Activities Tax or CAT), Texas (Margin Tax), and Washington state (Business & Occupation or B&O Tax), each unique in their own ways but included in the broad category known to public finance scholars as gross receipts taxes.[9] Gross receipts taxes have a bad reputation in Nevada, with proposals failing spectacularly in 2003 (0.25 percent on revenue above $450,000, with gaming and mining revenue exempt), 2011 (0.8 percent for any business with revenue above $1 million, less limited deductions and exempting health care providers), and 2014 (2 percent for any business with revenue above $1 million, less limited deductions).

Key Flaws of Gross Receipts Taxes Were Ignored While Designing the BLF

Many flaws were identified in previous gross receipts tax debates in Nevada: (1) taxation of unprofitable businesses, (2) different business types facing different tax burdens despite the flat rate, (3) pyramiding due to hidden taxation of inputs, (4) distortion of the economy by incentivizing vertical integration, and (5) lack of trust that the revenue would be widely used.

Aguero identified the second and third of these criticisms – different business types facing different tax burdens and hidden pyramiding due to taxation of inputs – as the fatal flaws and set out to craft a proposal to address them.[10] (The BLF proposal indisputably suffers from the other three flaws.) The key model proved to be Washington state, whose B&O Tax has evolved from a structure with six different industry classifications to 35 different industry-specific rates ranging from 0.3 percent to 3.3 percent in an attempt to address pyramiding.

Theoretically, B&O Tax rates are set so that horizontally-integrated, low-margin businesses (for example, a grocery store, manufacturing facility, or agricultural enterprise) pay lower B&O Tax rates than vertically-integrated, high-margin businesses (such as insurance, child care, or television broadcasting businesses), in the hope that effective tax rates on final goods and services are roughly similar. For example, commercial and industrial machinery equipment goes through an average of 3.9 levels of production before final sale, while sale of services usually goes through an average of 1.3 levels of production before final sale.[11] Washington’s goal is, therefore, a tax rate on advertisers that is about three times as high as the rate on manufacturers, such that the embedded tax percentage in the final sales price is equivalent. This is obviously an imprecise task given that each business is different, even changing year by year. A 2002 state commission found that the B&O Tax still pyramids significantly, despite the wide range of rates for each business.[12] Further, lobbyists have taken advantage of the wide variety of rates to obtain exemptions or lower rates for themselves and higher rates for their competitors.

The Proposed BLF Rates are Arbitrarily Calculated Using an Unrepresentative Sample of One Year of Data from Another State

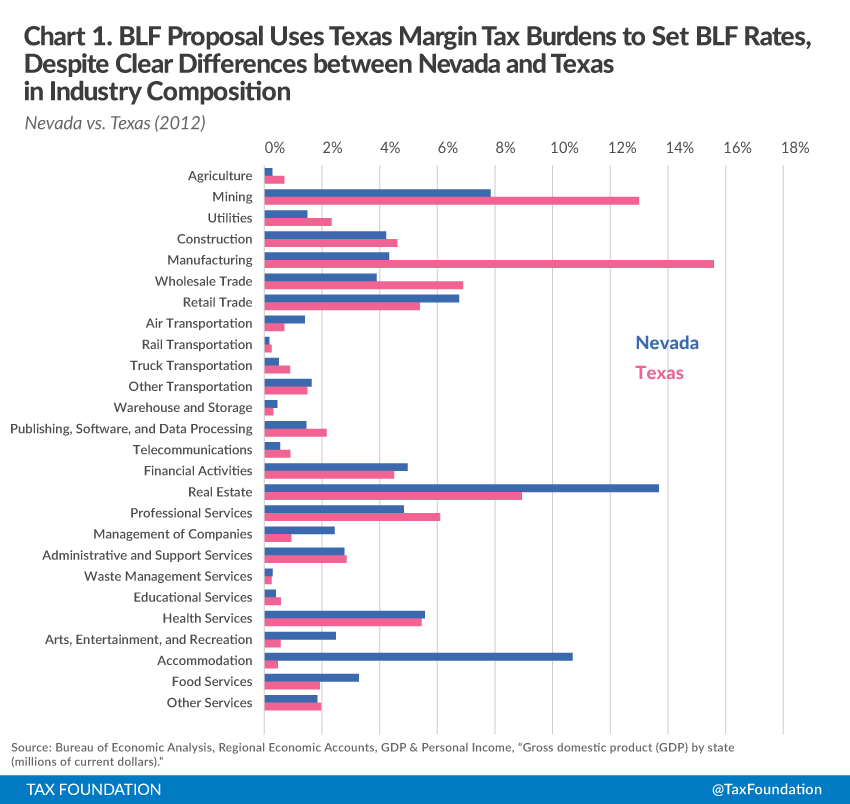

Aguero set out to develop Washington-style, industry-specific rates but with the end goal of matching the effective tax rates calculated by Texas for their Margin Tax for tax year 2011, despite significant economic differences between the two states and limited data from studying just one year (see Figure 1).[13] For example, the real estate, accommodation, and food services sectors are much larger in Nevada, while mining, manufacturing, and wholesale trades are much more prominent in Texas. Aguero’s explanation related to data availability, although a more plausible reason is likely a desire to replicate the effect of the Texas Margin Tax without the political danger of actually adopting the exact tax. Indeed, if the goal was to match the by-industry tax burden of a 1 percent margin tax, the simplest way would be to enact a 1 percent margin tax, not calculate the effective tax rates for each industry under such a tax, then work backward to craft revenue ranges and tax amounts for each to produce that effective rate.

That is what the BLF proposal does, to take one category (retail) as an example. The Texas study found that manufacturers in 2011 paid $706,417,000 in margin tax on gross receipts of $387,133,000,000, for an average effective tax rate of 0.182 percent. That 0.182 percent figure was applied to the BLF, then adjusted by factor of 54.7 percent to match the revenue goal of $250 million per year. (Some categories are increased because they face a reduced tax rate in Texas.) The resultant 0.10 percent rate was then applied against the revenue thresholds to produce the dollar amounts in the BLF table. Table 2 shows the calculation process for each industry category. Once the 27 different industry rates are factored in, the result is a tax rate schedule containing 1,811 possible flat-dollar amount tax liabilities (see Appendix A for the full table).

Table 2: How the BLF Uses 2011 Texas Data to Calculate the BLF Tax Rates |

|||||

|

Industry |

Texas Tax Paid, 2011 ($millions) |

Texas Gross Receipts, 2011 ($millions) |

Texas 2011 Effective Tax Rate |

Adjustment |

BLF Tax Rate |

|

Rail Transportation |

$2.9 |

$444 |

0.66% |

54.7% |

0.36% |

|

Telecommunications |

$185.7 |

$30,765 |

0.60% |

54.7% |

0.33% |

|

Educational Services |

$18.3 |

$3,252 |

0.56% |

54.7% |

0.31% |

|

Waste Management Services |

$21.1 |

$4,013 |

0.52% |

54.7% |

0.29% |

|

Publishing, Software, and Data Processing |

$92.8 |

$18,312 |

0.51% |

54.7% |

0.28% |

|

Real Estate |

$254.3 |

$50,833 |

0.50% |

54.7% |

0.27% |

|

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation |

$28.2 |

$5,879 |

0.48% |

54.7% |

0.26% |

|

Truck Transportation |

$30.7 |

$7,576 |

0.40% |

54.7% |

0.22% |

|

Accommodation |

$33.8 |

$5,683 |

0.60% |

54.7% |

0.22% |

|

Health Services |

$172.6 |

$45,330 |

0.38% |

54.7% |

0.21% |

|

Food Services (including restaurants) |

$61.7 |

$31,848 |

0.19% |

108.4% |

0.21% |

|

Professional Services |

$371.6 |

$102,639 |

0.36% |

54.7% |

0.20% |

|

Administrative and Support Services |

$82.5 |

$26,707 |

0.31% |

54.7% |

0.17% |

|

Other Services |

$66.1 |

$23,263 |

0.28% |

54.7% |

0.16% |

|

Utilities |

$165.4 |

$60,809 |

0.27% |

54.7% |

0.15% |

|

Management of Companies |

$239.3 |

$87,233 |

0.27% |

54.7% |

0.15% |

|

Other Transportation |

$77.5 |

$29,882 |

0.26% |

54.7% |

0.14% |

|

Warehousing and Storage |

$9.4 |

$3,692 |

0.26% |

54.7% |

0.14% |

|

Retail Trade |

$358.4 |

$321,462 |

0.11% |

107.6% |

0.12% |

|

Financial Activities |

$193.3 |

$86,802 |

0.22% |

54.7% |

0.12% |

|

Wholesale Trade |

$295.3 |

$293,751 |

0.10% |

109.4% |

0.11% |

|

Manufacturing |

$706.4 |

$387,133 |

0.18% |

54.7% |

0.10% |

|

Construction |

$143.8 |

$86,324 |

0.17% |

54.7% |

0.09% |

|

Agriculture |

$12.0 |

$9,489 |

0.13% |

54.7% |

0.07% |

|

Mining |

$320.3 |

$313,564 |

0.10% |

54.7% |

0.06% |

|

Air Transportation |

$9.7 |

$8,331 |

0.12% |

54.7% |

0.06% |

|

Unclassified |

$41.2 |

$16,124.0 |

0.26% |

54.7% |

0.14% |

|

Non-Employer Firms |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

$400 flat |

|

Foreign Filers |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

$400 flat |

| Source: Tax Foundation review of SB 252; Governor’s office; Texas Comptroller. |

Revenue Cliffs Result in Absurdly High Marginal Tax RateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. s, as High as 13 Million Percent

The industry rates are applied to gross receipts ranges, beginning at $125,001 and increasing in 67 increments of 15 percent up to just over $1.1 billion. Aguero stated the increments are designed to minimize “revenue cliffs” (situations in which an extra dollar in revenue results in more than an extra dollar in taxes), but the final proposal creates dozens of revenue cliffs for every industry.

For example, a small hotel earning $1,169,768 annually would pay an additional $356 in tax if it earned an additional dollar per quarter, for a tax rate of 8,900 percent on the marginal dollar. The highest marginal tax rate in the BLF is faced by rail transportation companies. On their next dollar earned after $931,596 per quarter, they would pay an additional tax of $139,739, for a tax rate of over 13 million percent on the marginal dollar. All industries face these revenue cliffs, which are disfavored by public finance scholars for their disincentive effects on earning additional revenue.

Table 3 shows the highest BLF tax rates for each industry that result from the use of revenue cliffs.

Table 3: Highest BLF Marginal Tax Rates by Industry |

|

|

Industry |

Highest BLF Marginal Tax Rate |

|

Rail Transportation |

13,973,900% |

|

Telecommunications |

12,711,300% |

|

Educational Services |

11,869,400% |

|

Waste Management Services |

11,048,700% |

|

Publishing, Software, and Data Processing |

10,669,800% |

|

Real Estate |

10,522,500% |

|

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation |

10,101,600% |

|

Truck Transportation |

8,523,300% |

|

Accommodation |

8,418,100% |

|

Food Services (including restaurants) |

8,165,500% |

|

Health Services |

8,018,200% |

|

Professional Services |

7,618,300% |

|

Administrative and Support Services |

6,502,900% |

|

Unclassified |

6,313,500% |

|

Other Services |

5,976,800% |

|

Management of Companies |

5,766,300% |

|

Utilities |

5,724,200% |

|

Other Transportation |

5,450,700% |

|

Warehousing and Storage |

5,387,600% |

|

Finance and Insurance |

4,693,100% |

|

Retail Trade |

4,672,000% |

|

Wholesale Trade |

4,251,100% |

|

Manufacturing |

3,830,200% |

|

Construction |

3,514,500% |

|

Agriculture |

2,651,700% |

|

Air Transportation |

2,462,200% |

|

Mining |

2,146,600% |

|

Source: Tax Foundation calculation of highest tax rate faced by each industry category in SB 252. |

Aguero Concedes Pyramiding Will Be a Problem with the BLF

Because Aguero targeted 2011 Texas tax paid, instead of attempting to equalize the embedded tax on the final sales price, pyramiding is not addressed and will be a significant problem. As explained by Professor Zodrow of Rice University:

On efficiency grounds, gross receipts taxes are problematic because they are primarily taxes on business inputs and such taxes are in general a relatively inefficient source of revenue. … [T]hey result in highly inefficient tax pyramiding, as multiple layers of taxation are applied to those products whose inputs happen to be transferred among firms at various stages in the production process. … The result is a haphazard pattern of effective tax rates across business inputs, which inefficiently distorts firm decisions regarding input choices. … [T]he tax pyramiding attributable to gross receipts taxes creates a tax bias toward vertical integration (organizing the production process so that multiple steps are carried out within a single firm), … reduc[ing] the efficiency of resource use within the state … [and creating] a bias against small firms, especially those that might be able to provide low cost services to larger firms. … [T]o the extent that tax pyramiding is shifted forward as higher consumer prices … it results in a haphazard pattern of consumer price distortions that inefficiently distort consumer decisions.[14]

Aguero acknowledged as much in March 2015 legislative testimony, stating that pyramiding is inherent in gross receipts taxes and will occur if the BLF is enacted.[15]

BLF Rates Do Not Correlate with Profitability, Resulting in Punitive Taxes for Some

The BLF tax rates are completely unrelated to firm profitability, as discovered in the Guinn Center’s recent analysis of SB 252.[16] When the BLF is expressed in terms of a corporate income tax (tax owed as a percent of profit), significant inequities arise. For example, the rail transportation BLF is the equivalent of a 58 percent corporate income tax, the data processing BLF is the equivalent of a 35 percent corporate income tax, and the restaurant BLF is the equivalent of a 5 percent corporate income tax. (See Table 4 for a full list.) Because the tax falls upon gross receipts, even businesses that are losing money will bear the burden of the restructured BLF.

The Guinn Center, while modestly in favor of the BLF as a concept, expressed “concern with the rates,” noting that “the business license fee rates do not correlate with the general profitability of the industry or with the contribution of the industry to Nevada’s gross domestic product (GDP).”[17] They concluded: “We have some concerns with the absence of articulated principles of fairness and equity informing the design of the rates.”[18]

Table 4: BLF Tax Rates Result in Widely Varying, and in Some Cases Punitive, Taxes on Profits |

|||

|

Industry |

BLF Tax Rate |

National Industry Profitability Rate |

Equivalent State Corporate Income Tax Rate |

|

Rail Transportation |

0.36% |

0.62% |

58% |

|

Telecommunications |

0.33% |

0.43% |

77% |

|

Educational Services |

0.31% |

7.00% |

4% |

|

Waste Management Services |

0.29% |

4.33% |

7% |

|

Publishing |

0.28% |

12.81% |

2% |

|

Software |

0.28% |

4.19% |

7% |

|

Data Processing |

0.28% |

0.80% |

35% |

|

Real Estate |

0.27% |

7.46% |

4% |

|

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation |

0.26% |

3.14% |

8% |

|

Truck Transportation |

0.22% |

1.65% |

13% |

|

Accommodation |

0.22% |

-1.11% |

|

|

Health Services |

0.21% |

5.10% |

4% |

|

Food Services (including restaurants) |

0.21% |

4.50% |

5% |

|

Professional Services |

0.20% |

4.19% |

5% |

|

Administrative and Support Services |

0.17% |

3.44% |

5% |

|

Other Services |

0.16% |

4.02% |

4% |

|

Utilities |

0.15% |

-4.98% |

|

|

Management of Companies |

0.15% |

62.04% |

0.2% |

|

Other Transportation |

0.14% |

3.41% |

4% |

|

Warehousing and Storage |

0.14% |

2.91% |

5% |

|

Unclassified |

0.14% |

||

|

Retail Trade |

0.12% |

2.71% |

4% |

|

Finance and Insurance |

0.12% |

16.75% |

1% |

|

Wholesale Trade |

0.11% |

2.38% |

5% |

|

Manufacturing |

0.10% |

5.56% |

2% |

|

Construction |

0.09% |

1.93% |

5% |

|

Agriculture |

0.07% |

2.69% |

3% |

|

Mining |

0.06% |

6.70% |

1% |

|

Air Transportation |

0.06% |

0.62% |

10% |

|

Source: Guinn Center for Policy Priorities. |

BLF Industry Categories are Arbitrarily Selected and Will Result in Tax Arbitrage and Economic Distortions

The 27 BLF industry categories are drawn from the North American Industry Classification System Code (NAICS), which classifies businesses by their primary activity. However, there are 19,255 NAICS codes, covering everything from abattoirs (slaughterhouses) to zucchini farming. The first two numbers in a NAICS code represent twenty broad categories, and each additional digit (up to six) provides additional levels of detail. For example, code 11 refers to agriculture, code 111 refers to crop production, code 1111 refers to oilseed and grain farming, and code 11111 refers to soybean farming.

The resulting BLF categories are a hodge-podge of NAICS codes: 15 of the categories are economic sectors (two-digit codes), 9 are subsectors (three-digit codes), 2 are a combination of several subsectors, and the final category is a catch-all “unclassified” category. Those familiar with NAICS recognize that the BLF industry categories are essentially arbitrary. Their origin, of course, comes from the Texas 2011 study, the purpose of which was to estimate the Margin Tax’s impact on certain selected sectors, not to define a comprehensive list of economic activity. The use of these categories for the BLF is, therefore, unsuitable.

The Guinn Center recognized this as well, describing the category list as being developed with the “absence of clear principles of equity and fairness.”[19] Citing the example of the BLF’s category of publishing, software, and data processing, “Under the revised Business License Fee structure, publishing, software, and data processing were grouped into one category and taxed at a rate of 0.276 percent, the fifth highest rate. However, the profitability rate for those industries varies significantly: publishing (12.81 percent), software (4.19 percent), and data processing (0.80 percent).”[20]

The fundamental problem with this list of 29 filer categories to represent the economy of Nevada is that it is no more right than any other list of categories that someone else could choose. Because using a different scheme of categorization – breaking down retail into boutique stores and dollar stores, for instance – would significantly change the tax burdens for large numbers of Nevada businesses, the categories are essentially arbitrary and contrived. The same applies for businesses that defy easy categorization; equipment repair and dating services both fall into an “other business services” category, even though they have little in common.[21]

A particularly pressing issue arises for those businesses that fall within more than one sector. It may seem simple for a firm to determine its industry and gross receipts level to identify the tax it owes. However, many businesses are multi-location and multi-industry, therefore settling on an accurate code will be difficult. For example, a business may engage in both truck transportation and warehousing. Under the new BLF, businesses with several locations would file a combined return even though each location must retain a separate business license with the state. A business with different locations could end up classified under different NAICS codes. Extensive guidance will need to be provided for firms that operate in more than one industry.

Supporters of the BLF have noted that businesses already designate a primary NAICS category on their existing business filings. At present, however, this decision is largely informational; should it form the basis of a company’s tax burden, decisions about industry classification would take on newfound significance.

More problematically, a truck company would be well-advised to morph into a warehousing company to minimize its tax burden. This pressure to vertically integrate for tax reasons — even to the point of developing conglomerates — is a common criticism of Washington’s B&O tax, with the resultant tax-arbitrage-induced business structures rendered less competitive on the national and global stage.[22] A tax system with different rates for different industries creates an environment that welcomes arbitrage in order to generate tax savings. In addition, it creates an incentive for tax-disadvantaged firms (that is, those with higher industry rates) to lobby for special carve-outs and lower rates. This constant fiddling with the tax rates has occurred for years in Washington state.[23]

The Proposed BLF Structure Is Complicated and Will Create High Administration and Compliance Costs

Businesses are required to indicate their industry classification with their initial filing, and should their primary business activity change, they would be required to apply for a category change (which must be approved by the Department of Taxation per section 19 of SB 252). Since payors are legally obligated (at section 19(2)(c)) to remit the license fee associated with “the business category in which the business conducted by the person was primarily engaged during the calendar quarter,” businesses experiencing a shift in what constitutes their primary business activity could face a legal quandary, statutorily obligated to pay based on a new category but prevented from adopting that category without prior approval of the Department. Quarterly filing based on revenue would also require additional record-keeping beyond that required for paying annual federal corporate income taxes.

Given the authority of the Department of Taxation to auditA tax audit is when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) conducts a formal investigation of financial information to verify an individual or corporation has accurately reported and paid their taxes. Selection can be at random, or due to unusual deductions or income reported on a tax return. all factual questions pertaining to BLF filings, the state would likely see appeals when taxpayers and the state do not agree on the firm’s industry classification – especially when a lower tax rate is at stake. Currently, a Nevada business license is obtained through the Secretary of State’s office and is paid annually. Businesses are accustomed to making a preliminary identification of their primary business activity; when a business registers with the Secretary of State to file its first listing with the state and pay this fee, the businesses must report its legal form of organization and also report “which industries apply to [its] business” based on NAICS. However, while this data is available in the Secretary of State’s business database, it takes on greater significance when it forms the basis for levying a new business tax and will have to be confirmed via audits to ensure proper taxes are being paid.

History demonstrates how difficult it can be to base business tax categories on NAICS codes. In 2005, Nevada Senate Bill 391 was introduced to recategorize pawn shops and collection agencies, which were placed under the NAICS “financial institutions” category and thus had to pay a higher MBT rate. An investigation committee under Senator Mike McGinness and Assemblyman David Parks suggested avoiding NAICS codes when defining financial institutions and recommended that Nevada “replace the current language … which relies on NAICS to classify or define financial institutions.”[24] The Department of Taxation reported that April that it had “already done over 500 appeals on this issue” and had hundreds more outstanding.[25] The appeals involved sorting businesses into two categories, financial and non-financial, for purposes of the Modified Business Tax. The BLF proposal would sort businesses into 29 categories. Texas has also faced considerable ongoing litigation regarding industry categories, even though they only have three (wholesalers, retailers, all other).[26]

Contrary to expectations of quick implementation, the BLF will likely require a long lead time of rule-writing and data-gathering before revenue can be collected. Ohio took seven years to phase in its Commercial Activities Tax, Texas took three years to begin collecting its Margin Tax (and collections were off estimate by one-third even with the long lead time), and Washington state has modified its B&O Tax almost constantly over its 80 year existence. Quick implementation is inviting disaster.[27]

BLF Revenue Estimates Are Potentially off by Hundreds of Millions of Dollars

Senators Aaron Ford (D) and Becky Harris (R) both asked a key question in the legislative hearing on the BLF: do sponsors anticipate any change in situs for the 180,000 businesses that register in Nevada but have no payroll in the state?[28] Aguero said no, and in fact, the Governor’s proposed budget relies on a projection of ten percent growth in the number of Nevada business licenses, from the present 308,000 to 340,000.

This is likely an unrealistic assumption, given that many of the 180,000 non-employer businesses are in Nevada due to its low license fee.[29] Governor Sandoval has spoken frequently of his desire to tax precisely these businesses, which – because they have no payroll – are not subject to the MBT. It stands to reason that a considerable number may leave if their fee rises from $200 per year to tens of thousands of dollars.[30] The Nevada Registered Agent Association commissioned a team of five academics to conduct a price-elasticity evaluation of such a scenario, and they concluded that the BLF as proposed would cause a net drop of 124,000 registered businesses in the state and a 55 percent reduction in new filings.[31]

Because the supporting materials supplied by the Governor’s office do not break down revenue estimates by sector or by firm type (they present only the aggregate revenue estimate), it is not clear exactly how much such a reduction would impact the revenue estimate. A back-of-the-envelope estimate of subtracting 124,000 business filings, taking the fact that the average Nevada business would pay $811 under the BLF, means that the BLF would generate $150 million per year instead of the projected $250 million per year, meaning the revenue estimate would be overstated by $100 million per year, or $200 million over a biennium.

The BLF Proposal Violates the Principle of Transparency by Mislabeling an Obvious Tax

Fees defray the cost of providing a particularized benefit while taxes generate revenue for general purposes.[32] This is not just semantics or an obscure legal doctrine: policymakers have a strong incentive to avoid labeling something a “tax” so as to avoid the political poison of being labeled a “tax hiker.” For some elected officials, the best tax is one that raises lots of money without anyone calling it a tax. But taxes that are not called taxes violate the principle of transparency by depriving taxpayers of information needed to make meaningful choices about priorities. This is especially important for gross receipts taxes, which are hidden in consumer prices and are less transparent than other forms of taxation. Further, many states (including Nevada) require legislative supermajorities to enact taxes, so terminology is important.

The highest courts in all but two states distinguish between taxes, fees, and penalties by looking at the purpose of the charge. Nevada is one of those states, with the Nevada Supreme Court holding that a charge is a fee only if it (1) applies to the direct beneficiary of a particular service, (2) is allocated directly to defraying the costs of providing the service, and (3) is reasonably proportionate to the benefit received.[33] When the “true purpose” of the charge becomes raising revenue, as evidenced by the transfer of the funds to unrelated general purposes, the charge becomes a tax.[34]

The current BLF, a modest dollar amount to cover the costs of registration and filing, fits the definition of a fee. But the proposed BLF, designed to raise hundreds of millions of dollars for state education spending, no longer directly provides a particularized and reasonably proportionate benefit to those who pay the BLF. State education spending benefits all Nevada residents, not just BLF payors. For these reasons, the proposal is properly termed a tax.

Proposed BLF Likely Violates the Interstate Commerce Clause and Federal Law

Conceding that state and local governments have the power to tax, the United States Supreme Court has generally limited its scrutiny of gross receipts taxes to ensuring that they do not infringe on Congress’s exclusive authority to regulate interstate commerce. Accordingly, Indiana’s 1933 general gross receipts tax, adopted in tandem with a reduction in property taxes, was found unconstitutional because “the tax includes in its measure, without apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’ profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income or other business taxes. U.S. states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders. , receipts derived from activities in interstate commerce.”[35] Even if a business’s income only partly comes from interstate commerce, a gross receipts tax imposed on it will be void.[36] The premise underlying such strong and consistent judicial treatment of general gross receipts taxes is the fear that if many states adopted such taxes, firms would be “expose[d] to multiple tax burdens, each measured by the entire amount of the commerce.”[37]

Statutes can be crafted to survive this scrutiny. “Taxation measured by gross receipts from interstate commerce has been sustained when fairly apportioned to the commerce carried on within the taxing state … [such that] it is a practical way of laying upon the commerce its share of the local tax burden without subjecting it to multiple taxation not borne by local commerce.”[38] It must be done carefully; West Virginia’s wholesaler gross receipts tax remained discriminatory even though in-state producers faced a rate three times that of out-of-state producers. This was because West Virginia also imposed a manufacturing tax, and if other states adopted the same scheme, the Court found, West Virginia’s in-state producers would be subject to less tax than out-of-state producers.[39]

It is probably for this reason that the BLF’s designers established a flat rate of $400 for foreign filers and wrote situs rules designed to ensure interstate activity is never subject to more tax than intrastate activity. In a legislative hearing, Senator Michael Roberson (R) inquired as to why interstate and intrastate activities were taxed differently; while this question was not answered directly, doing otherwise would likely be unconstitutional.

Most likely, unconstitutional provisions remain in the BLF regardless. The analogous Washington state B&O Tax provides an instructive example, as it has been contested in court numerous times in its history. The original tax, enacted in 1935, taxed most sectors at a rate of 0.25 percent. Today, the B&O Tax has 35 different rates, most at 0.484 percent.[40] As the rate has gone up, “numerous credits, deductions, and rate changes have been implemented.”[41] In 2000, the Economic Opportunity Institute counted 98 B&O exemptions, deductions, and credits “targeted toward numerous business activities within the Washington economy,” thirty of which were adopted since 1990.[42] These changes first arose as an effort to equalize tax burdens to avoid court rulings striking down B&O taxation of interstate transactions.[43] In 1987, the Supreme Court struck down a B&O exemption that waived manufacturing receipts from taxation where a business engaged in both manufacturing and wholesaling.[44] Although criticized for its internal inconsistency,[45] Tyler Pipe and other recent decisions demonstrate that the Court will closely examine gross receipts tax statutes that result in potential or real multiple taxation. Evidence for such discriminatory intent will not be hard to find, with several positive references in the legislative hearing record about the BLF’s ability to export tax burdens to out-of-state businesses.

More problematic for the BLF’s legality is the punitive rate on rail transportation, the highest for all the industry categories. The federal Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform (4-R) Act prohibits states from imposing property or sales taxes on railroads that are greater than those imposed on comparable industries, as well as “another tax that discriminates against a rail carrier.”[46] In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that the term “another tax” is broadly drafted, and that a railroad taxpayer can take into account tax burdens or exemptions faced by other transportation carriers.[47] The Washington state B&O Tax and the Texas Margin Tax avoided this problem by taxing all transportation at the same rate, but the Nevada BLF proposal explicitly imposes a higher tax rate on rail transportation than on water transportation, air transportation, or even “all general and commercial taxpayers.”[48] The BLF rate on rail transportation undoubtedly violates the 4-R Act, and some other BLF rates may violate analogous federal statutes by discriminating for or against certain business types.

Conclusion

Gross receipts taxes inherently pyramid, distort business structures, and tax unprofitable businesses. For these reasons, they are uniformly panned by public finance scholars and have been discarded by nearly every jurisdiction that has ever adopted them. Establishing variable rates by type of business is not a new innovation, as Washington state has tried to do so for decades. Studies of their experience demonstrate that it has not mitigated pyramiding, and the differential rates have led to a general sense of unfairness in that state’s tax code. The complex nature of gross receipts taxes is evidenced by the Texas Margin Tax experience, which, despite several years of pre-collection planning, has led to unending litigation, constant fiddling with the tax rates, and missed revenue targets. Both states are now seriously considering proposals to significantly reduce or even repeal their taxes. Nevada would be well advised to learn from their experiences.

Nevada has other tax reform options. The Modified Business Tax is stable, simple, can be broadened by paring back exemptions enacted in the last few years, and can be collected immediately. The property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. , a broad and stable tax, is in need of reforms to simplify it and reduce distortions. The sales tax, Nevada’s revenue workhorse, would benefit from proposed studies to broaden its base and lower its rate, along with action to address the narrow nature of the Live Entertainment Tax. These approaches would focus on fixing what Nevada already has, without layering on a complex, arbitrary tax that will do long-term harm to Nevada’s economic growth.

Appendix A: Restructured Business License Fee Tax Schedule

[1] The authors are grateful to the public finance and state tax scholars who assisted our research and analysis of the Nevada BLF proposal, including Dr. John Mikesell, Professor of Public Finance at Indiana University and author of the textbook Fiscal Administration; David Brunori, Research Professor of State Taxation and Public Policy at George Washington University and author of the textbook State Tax Policy and the book The Future of State Taxation; Dr. Antony Davies, Associate Professor of Economics at Duquesne University; Dr. Fred Thompson, Professor of Public Management and Policy at Williamette University; Dr. Morris Coats, Professor of Economics at Nicholls State University (Louisiana); and Dr. Pavel Yakovlev, Associate Professor of Economics at Palumbo Donahue School of Business (Pennsylvania). We are also grateful to the past public finance research into the Washington B&O tax by Dr. Andrew Chamberlain and Dr. Patrick Fleenor, which is incorporated in our analysis.

[2] See, e.g., KPMG, Cat Got Your Tongue? Navigating the Complexities of Ohio’s New Commercial Activity Tax (2005), http://us.kpmg.com/microsite/tax/salt/perspectives/Fall_2005-02.asp; Joseph Henchman, Ohio Officials Agree to Cancel Income Tax Cut, Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog (Dec. 2009), https://taxfoundation.org/blog/ohio-officials-agree-cancel-income-tax-cut; Billy Hamilton, The Tax That Fell to Earth: Lessons From the Texas Margin Tax’s Launch, 57 State Tax Notes 671 (Sep. 2010); Scott Drenkard, The Texas Margin Tax: A Failed Experiment, Tax Foundation Special Report No. 226 (Jan. 2015), https://taxfoundation.org/article/texas-margin-tax-failed-experiment; Liz Malm & Jared Walczak, The Steadily Growing Complexity of the Washington Business & Occupation Tax, Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact (forthcoming Apr. 2015).

[3] See, e.g., Liz Malm, Joseph Henchman, Jared Walczak, & Scott Drenkard, Simplifying Nevada’s Taxes: A Framework for the Future (Jan. 2015), https://taxfoundation.org/article/simplifying-nevadas-taxes-framework-future.

[4] Nev. Rev. Stat. § 76.010 et seq. The current BLF is paid by all persons conducting business in Nevada with or without a location or employees except governmental entities; nonprofit religious, charitable, or educational associations; a person who operates an in-home business which generates less than 66-2/3% of the average annual wage; or a business that creates or produces motion pictures.

[5] S.B. 252, Nev. 78th Sess. (2015), https://www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/78th2015/Bill/1732/Overview. The proposed BLF would be collected on most types of business receipts from the sale of goods or revenue realized in the performance of a service” — that is, gross receipts.

[6] Hearing on S.B. 252 Before the Joint Meeting of the Senate Committee on Revenue and Economic Development and the Assembly Committee on Taxation, 78th Sess. (Mar. 18, 2015), https://www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/78th2015/Meeting/3288?p=1003288.

[7] In FY 2014, there were 47,146 Nevada businesses with payroll of $38.3 billion, of whom 34,955 (74.1 percent) were fully exempt from the MBT due to a quarterly exemption threshold enacted in 2011 at $62,500 and raised in 2013 to $85,000. This leaves 12,191 (25.9 percent) of Nevada businesses with payroll as MBT taxpayers. See Fiscal Analysis Division, Modified Business Tax on Nonfinancial Businesses by NAICS Business Category for FY 2014, https://www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/78th2015/ExhibitDocument/OpenExhibitDocument/10615/MBT-NFI_FY2014%20Data%20Tables%202%20and%203.pdf.

Nevada is second only to Delaware as a popular location for non-employer businesses to locate, with approximately 180,000 non-employer businesses (and 30,000 sole proprietor businesses) paying the existing BLF but not the MBT. Thus, while only about 4.7 percent of Nevada businesses pay the MBT, 80 percent of state payroll ($30.5 billion) is subject to the MBT, and if the MBT exemption were removed, 100 percent of businesses with payroll would be paying the MBT, and 100 percent of Nevada businesses would be paying the MBT and/or the existing BLF.

[8] A broad-based MBT would capture all businesses with payroll; the proposed graduated-rate BLF structure would capture all businesses with more than $125,000 in Nevada Gross Revenue. These categories would be largely, but not entirely, synonymous. Some small businesses could have an employee but less than $125,000 in gross revenue, and thus be subject to a broad-based MBT but not the BLF. Some out-of-state firms will have more than $125,000 in Nevada gross receipts but no in-state employees (e.g., an out-of-state advertising firm that works with clients in Nevada), and thus subject to the graduated-rate BLF but not an expanded MBT. Still other firms might have Nevada employees but contract with out-of-state firms (e.g., an independent, Nevada-based call center contracting with out-of-state firms), thus having no Nevada gross receipts, making them taxable under a broad-based MBT but not a graduated-rate BLF. These differences are, however, the exceptions that prove the rule. For all practical purposes, the number of businesses subject to a broad-based MBT and the graduated-rate BLF structure would be practically identical.

[9] Hybrid business taxes including a gross receipts component also exist at the state level in Delaware and New Hampshire and at the local level in Virginia. Broad-based sales taxes in Hawaii and New Mexico are sometimes inaccurately described as gross receipts taxes because the legal incidence of the tax in those states falls on business instead of consumers, but in all other respects the taxes best fit the category of sales taxes.

[10] Hearing on S.B. 252 Before the Joint Meeting of the Senate Committee on Revenue and Economic Development and the Assembly Committee on Taxation, 78th Sess. (Mar. 18, 2015), https://www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/78th2015/Meeting/3288?p=1003288.

[11] Andrew Chamberlain and Patrick Fleenor, Tax Pyramiding: The Economic Consequences of Gross Receipts Taxes, Tax Foundation Special Report No. 147 (Dec. 2006) at 5, https://taxfoundation.org/sites/default/files/docs/sr147.pdf.

[12] Washington State Tax Structure Study Committee, Tax Alternatives for Washington State: A Report to the Legislature, Volumes 1 & 2 (Nov. 2002), http://dor.wa.gov/content/aboutus/statisticsandreports/wataxstudy/final_report.htm.

[13] The report used is Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, The Business Tax Advisory Committee Report to The 83rd Texas Legislature (Jan. 2013), http://www.window.state.tx.us/taxinfo/btac/96-1364_BTAC_Report_2013.pdf.

[14] George R. Zodrow, Texas Tax Options, James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, Rice University (Jan. 2006), http://bakerinstitute.org/media/files/Research/a3823166/wp_2006002.pdf.

[15] Hearing on S.B. 252 Before the Senate Committee of the Whole, Nev. 78th Sess. (Mar. 19, 2015), https://www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/78th2015/Meeting/3312?p=1003312.

[16] Guinn Center for Policy Priorities, The Business License Fee: What We Still Don’t Know (Mar. 2015), http://guinncenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Guinn-Center-Tax-Policy-Brief-for-Legislators_March_17.pdf.

[17] Id. at 5.

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Id.

[21] “There are four kinds of business: tourism, food service, railroads, and sales. [Pause.] And hospitals slash manufacturing. And air travel.” Michael Scott, The Office (Season 3, Episode 6, “Business School,” aired Feb. 15, 2007).

[22] See, e.g., Washington State Tax Structure Committee, Tax Alternatives for Washington State: A Report to the Legislature (Nov. 2002) at Chapter 9 and Appendix C, http://dor.wa.gov/content/aboutus/statisticsandreports/wataxstudy/final_report.htm; B&O Tax Pyramiding in Petroleum Distribution, Washington Research Council Special Report (Jan. 18, 2010), https://researchcouncil.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/botaxpyramidinginpetrodist.pdf; Carl Gipson, Business & Occupation Tax Reform, Part II, Washington Policy Center Policy Note (Aug. 2008), https://www.washingtonpolicy.org/sites/default/files/B&OPart2.pdf; and Safeway, Inc. v. Department of Revenue, 978 P.2d 559 (Wash. Ct. App. 1999).

[23] Liz Malm & Jared Walczak, The Steadily Growing Complexity of the Washington Business & Occupation Tax, Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact (forthcoming Apr. 2015).

[24] Nevada Legislative Committee on Taxation, Public Revenue, and Tax Policy, Bulletin No. 05-18 (Jan. 2005), at 31, https://www.leg.state.nv.us/Division/Research/Publications/InterimReports/2005/Bulletin05-18.pdf.

[25] Minutes of the Nevada Senate Committee on Taxation (Apr. 7, 2005), http://www.leg.state.nv.us/73rd/Minutes/Senate/TAX/Final/4095.pdf.

[26] Scott Drenkard, The Texas Margin Tax: A Failed Experiment, Tax Foundation Special Report No. 226 (Jan. 2015) at 5-6, https://taxfoundation.org/article/texas-margin-tax-failed-experiment.

[27] See, supra, KPMG, Cat Got Your Tongue? Navigating the Complexities of Ohio’s New Commercial Activity Tax (2005), footnote 2.

[28] See, supra, Hearing on S.B. 252 Before the Senate Committee of the Whole, Nev. 78th Sess. (Mar. 19, 2015), footnote 15.

[29] Assemblywoman Marilyn Kirkpatrick asked witnesses to what extent filings dropped after the 2009 increase in the BLF from $100 to $200. Witnesses replied that filings dropped, although separating out the recessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. ary impact and the fee increase is difficult. Estimated BLF-paying entities peaked in 2008 at 321,000; subsequent years were 2009 (290,000), 2010 (280,000), 2011 (287,000), 2012 (282,000), 2013 (290,000), and 2014 (300,000).

[30] Even setting aside the new graduated rate structure, the $200 increase in the base license fee will have a significant impact on businesses which tend to file for a sizable number of business licenses for financial or liability reasons.

[31] Dr. David Swanson, Dr. Robert Schmidt, Dr. John Ziebell, Dr. David Atkinson, and Katriina Talja, Proposed Nevada Business License Fee Increase & Gross Receipts Margin Tax (Mar. 2015).

[32] See Joseph Henchman, How is the Money Used? Federal and State Cases Distinguishing Taxes and Fees (2013), /wp-content/uploads/2013/03/TaxesandFeesBook.pdf.

[33] Clean Water Coalition v. The M Resort, LLC, 255 P.3d 247, 256 (Nev. 2011).

[34] Id. at 257.

[35] J.D. Adams Mfg. Co. v. Storen, 304 U.S. 307, 311 (1938).

[36] See Fisher’s Blend Station, Inc. v. Tax Comm’n of State of Washington, 297 U.S. 650, 656 (1936).

[37] Gwin, White, & Prince, 305 U.S. at 439.

[38] Western Live Stock v. Bureau of Revenue, 303 U.S. 250, 257 (1938). Interestingly, that case involved New Mexico’s 2 percent gross receipts tax on newspaper and magazine advertising; Grosjean was not cited by the Court.

[39] Armco, Inc. v. Hardesty, 467 U.S. 638, 644 (1984).

[40] State Tax Guide, CCH Incorporated, at 9141-6 to 9141-7 (May 2006 update).

[41] Jason Smith, A Concise History of Washington’s Tax Structure, Economic Opportunity Institute Blueprint, at 8, http://www.eoionline.org/Taxes/WATaxHistory.pdf.

[42] Id. at 8-9.

[43] Gwin, White, & Prince, Inc., see supra note 7. See also Smith, at 8 (“In response, the Washington Legislature implemented several specific credits to reduce the possibility of double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. for manufacturing firms that do business in this and other states.”).

[44] Tyler Pipe Industries, Inc. v. Washington State Dept. of Revenue, 483 U.S. 232 (1987).

[45] E.g., David F. Shores, “State Taxation of Gross Receipts and the Negative Commerce Clause,” 54 Mo. L. Rev. 555, 589 (1989) (“[T]he Court first found that the manufacturing and wholesaling taxes [were discriminatory because they] created a risk of multiple taxation for interstate transactions which did not exist for intrastate transactions. … Yet for purposes of the apportionment issue, the Court said there was no risk of multiple taxation because it had already characterized the taxes as noncompensating. Obviously, the Court cannot have it both ways,”). The Court rejected Tyler Pipe’s argument that the wholesaling tax, which could not be waived, was not fairly apportioned to account for activity in different states. The Court stated that “wholesaling … must be viewed as a separate activity conducted wholly within Washington that no other State has jurisdiction to tax.” Tyler Pipe, 483 U.S. at 251. Shores suspects that multiple taxation of gross receipts would be found unconstitutional only if it is facially discriminatory. See Shores, 54 Mo. L. Rev. at 589-90.

[46] 49 U.S.C. § 11501(b)(4).

[47] CSX Transp. v. Ala. Dept. of Revenue, 562 U.S. 277 (2012).

[48] Ala. Dept. of Revenue v. CSX Transp., No. 13-553 (U.S. Mar. 4, 2015).