Key Findings

- Businesses contribute significantly to taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. collection through the taxes they are legally liable to pay and the taxes they are required to collect and remit on behalf of others.

- Businesses in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) pay an average of 37.8 percent of the total taxes collected.

- Czechia has the most “business dependent” tax system, with businesses contributing 54.7 percent of all collections. Fifteen countries receive more than 40 percent of their total revenues from businesses.

- Businesses in the OECD also collect and remit an average of 47.4 percent of the total tax revenues.

- On average, businesses in the OECD are liable for collecting, paying, and remitting more than 85 percent of the total tax collection.

- In Lithuania, Chile, Germany, Slovenia, and Czechia, businesses pay and remit more than 93 percent of all taxes.

- Policymakers should weigh the benefits and drawbacks of increasing the tax burden on businesses because the economic burden of these tax hikes will fall on workers through lower wages, shareholders through lower returns, or consumers through higher prices.

Introduction

“Tax fairness” and the role of corporations in a country’s tax system have been lingering themes in the international debate for years. But in this debate, “fairness” is usually only defined by looking at a firm’s corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rather than evaluating all of the functions businesses serve in the tax system. Going back more than a decade, advocacy groups have claimed that the inability of developing countries to provide basic services is due to corporations not paying their fair share.[1] In 2018, the European Commission advocated for a “Fair Taxation of the Digital Economy,”[2] and, in 2020, published a tax action plan for “Fair and Simple Taxation Supporting the Recovery Strategy.”[3] The problem with “tax fairness” is that there is no empirical standard for what constitutes a “fair share” of the tax burden. However, recent studies show that businesses and corporations contribute significantly more to tax collection than the current rhetoric would suggest. A recent study finds that for every €1 in corporate income tax paid, companies paid an additional €0.89 in other business taxes and submitted another €2.22 as revenue collecting agents for governments.[4]

A 2015 study by economists at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimated that domestic and foreign corporations contribute approximately $3.2 trillion (€2.9 trillion) in taxes to developing countries, accounting for nearly half of their total tax revenues. Within this figure, foreign multinational affiliates were responsible for $725 billion (€662 billion), representing about 11 percent of the total tax collections in developing countries.[5]

UNCTAD researchers also issued a warning against raising taxes on multinational companies: “[A]ny policy action aimed at increasing fiscal contribution and reducing tax avoidance . . . will also have to bear in mind the first and most important link: that of tax as a determinant of investment.”[6] In addition, the last UNCTAD report found that foreign direct investment fell by 2 percent in 2023, and the decline exceeded 10 percent after excluding a few European economies that registered large swings in investment flows.[7]

In addition to direct payments, businesses also collect and remit a variety of taxes on behalf of others, such as value-added and sales taxes, withheld income taxes, and employee social security contributions. This function simplifies tax collections for governments. The following report sheds light on the proportion of taxes that businesses pay directly or are legally liable to collect and remit while bearing a large share of the compliance cost of the tax system.

Types of Business Tax Payments in OECD Countries

When most people think of business taxes, they tend to think of the corporate income tax (CIT). However, business taxation is wider than the legal liability of CIT alone, encompassing many other taxes for which businesses are legally liable. Additionally, businesses have numerous other taxes that they are legally liable to remit on behalf of others, such as workers and consumers.

In this report, tax collection data is used to calculate the relative amount of taxes that businesses either pay directly or remit to governments in 38 OECD countries and four additional European countries: Bulgaria, Croatia, Malta, and Romania.

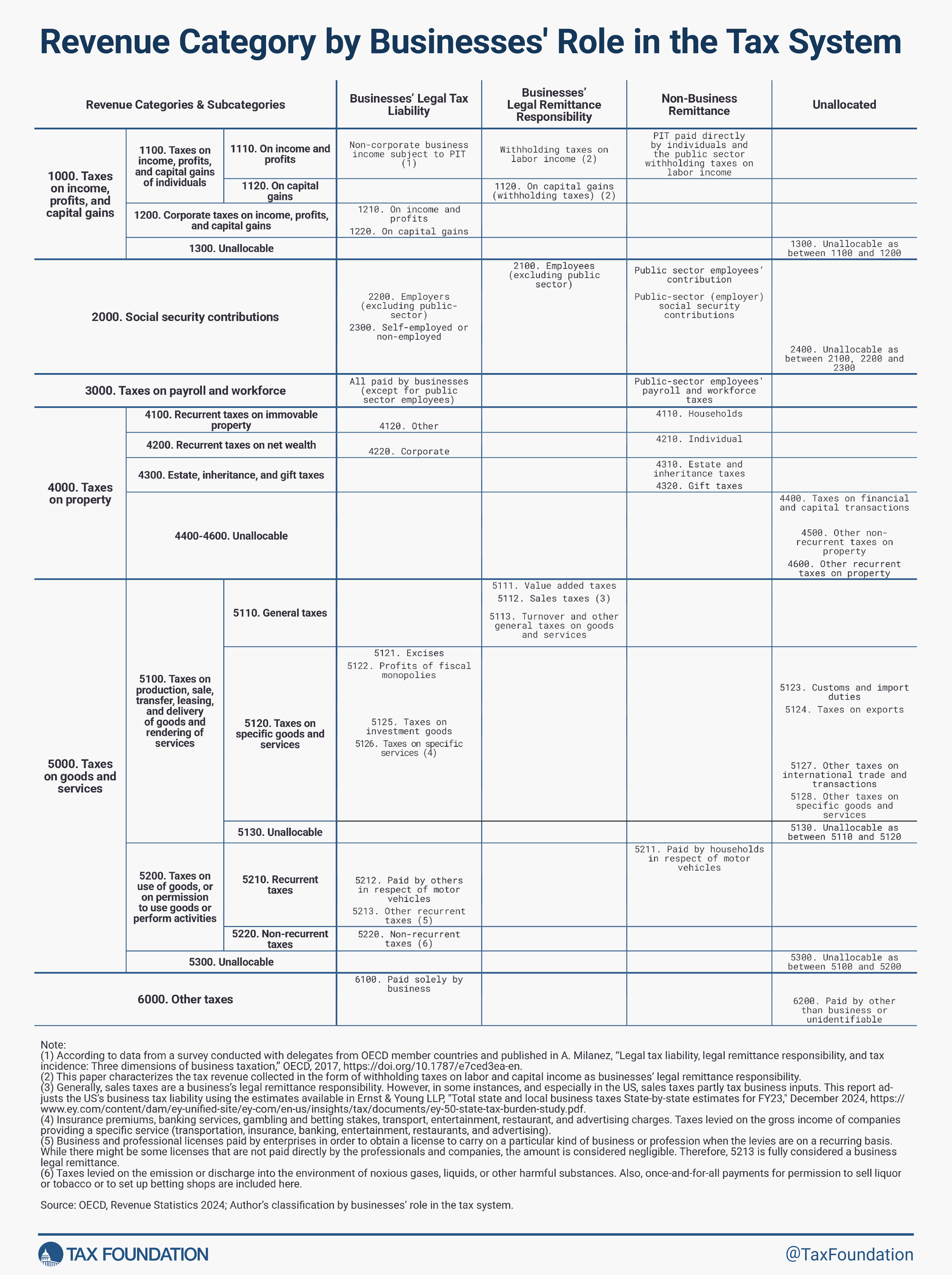

In Table 1, the revenues are separated into four categories: businesses’ legal tax liability, businesses’ legal remittance responsibility, non-business remittance, and unallocated revenue.

Legal Tax Liability

The taxes for which businesses are legally liable include corporate income tax, non-corporate business income tax, private sector employer’s social security contributions, payroll taxes, excise taxes, and taxes on investment goods. It also includes the business portion of recurrent taxes on immovable property, net wealth, motor vehicles, and other licenses or taxes paid solely by businesses.

Legal Remittance Responsibility

As significant as the direct contribution of businesses is, they play an even larger role for governments by collecting taxes and remitting them on behalf of others.

Businesses’ legal remittance responsibility includes withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount the employee requests. taxes on the income earned by employees or the capital income earned by shareholders, the employee’s share of social security contributions, and value-added and sales taxes paid to retailers by customers.

Non-Business Remittances

The revenues collected by governments, called non-business remittances, consist of personal income taxes paid directly by taxpayers, the withholding taxes and sector social security contributions governments pay on behalf of civil servants, property taxes and net wealth taxes paid by households, and estate and gift taxes.

The remainder is the revenue amount that can’t be allocated to either of the three categories above.

The Economic Incidence of Business Taxes and Beyond

There are two types of tax incidenceTax incidence is a measure of who bears the legal or economic burden of a tax. Legal incidence identifies who is responsible for paying a tax while economic incidence identifies who bears the cost of tax—in the form of higher prices for consumers, lower wages for workers, or lower returns for shareholders. : legal incidence and economic incidence. The legal incidence of taxes is borne by those with the legal obligation to remit the tax payments to governments. The legal incidence is established by law and tells us which individuals or companies must physically send the tax payments. The legal incidence of taxes is generally very different from the final economic incidence. It has long been recognized that the economic burden of the taxes remitted by businesses tends to fall on workers through lower wages, shareholders and owners through lower returns on capital investments, or consumers through higher prices.

Economists have studied the economic incidence of the corporate income tax since the 1960s. While many of the earliest studies tended to conclude that in closed economies owners of capital bore the lion’s share of the cost of the corporate income tax, more recent studies, considering open economies, are finding that more of the burden is falling on labor, although the share will depend on various factors and methods of measurement. Given that labor is generally less mobile than capital, and capital owners can avoid domestic taxes by shifting investments abroad, increases in corporate income tax can lead to domestic capital outflows. This reduction in domestic capital diminishes the return on labor, subsequently lowering wages.

For example, studies comparing cross-country differences have typically found that higher corporate tax rates are associated with lower wages. These studies estimate that between 45 percent and 400 percent of the burden of the corporate income tax falls on workers.[8]

How could a tax fall 400 percent on workers? The impact of the corporate income tax on the economy is much larger than the actual amount of taxes collected. Additionally, the overall size of the wage base is many times the amount of the corporate taxes collected, so a small increase in the corporate tax can have a relatively large effect on wages. For example, in the European Union, corporate income taxes totaled €548 billion in 2023.[9] By contrast, wages and salaries in the EU were €8.1 trillion—15 times larger than corporate tax collections.[10] Therefore, it makes sense why studies found that for every €1 of corporate income taxes collected by a high corporate tax rate, the overall amount of aggregate worker wages fell by up to €4, or 400 percent of the tax increase.[11]

Research comparing corporate income tax rates across US states revealed a similar range of outcomes. One study found that workers bore 30 percent of the corporate tax burden, while another study suggested that the burden could be as high as 360 percent, driven by a broad reduction in overall worker wages.[12]

Other researchers looked at the incidence of the corporate income tax on wages in situations where workers and employers negotiate wages frequently. A study of corporate tax changes on worker wages in Germany found slightly more than half of the corporate tax burden falls on workers.[13] A similar study in the US found that workers captured 54 percent of the benefits when corporate tax rates were lowered.[14]

When looking beyond corporate income tax and including personal income taxes levied on non-corporate businesses, a study found that a 1 percent decrease in business taxes increases establishment growth by 3 to 4 percent over 10 years.[15]

Taxing Labor

Economists have generally found that taxes on labor income, such as social security and payroll taxes, tend to be borne by workers through lower wages. However, some studies have found that not all such taxes are borne by workers; some of the burden can be shifted to employers and consumers, although the extent of this shift is unclear.

A Canadian province-level study found a negative impact of payroll taxes on wages and employment. A one percent increase in tax rates was associated with a wage reduction between 1.7 percent and 3.4 percent.[16] Additionally, a sector-level report found that following a 1 percent increase in the general payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. , annual wage growth drops by between 0.3 percent and 0.5 percent.[17]

Taxing Consumption

Similarly, value-added taxes (VAT) and sales taxes are generally thought to be entirely borne by consumers, although how much of the tax is passed on to consumers may depend upon the market power of the seller. Some studies have found that more than 100 percent of the tax can be passed on to consumers. One study of cigarette tax increases found that a €1 increase in the tax resulted in price increases of as much as €1.13.[18]

A more recent study that estimates the impact of changes in the standard rate of VAT on consumer price finds that changes in VAT standard rates are fully passed through to consumers. However, the extent of pass-through is significantly less for reduced rates, at around 30 percent. The same paper finds that the impact on prices is almost zero for the removal of certain items from the VAT base, through exemption or zero-rating, suggesting that the magnitude of tax incidence is highly dependent on the tax design.[19]

Legal Remittance Responsibility

Although the topic of how tax remittance responsibility affects the ultimate economic burden of taxes is of great interest to policymakers, this area has received little research attention.

Analyzing changes in the point of collection for diesel taxes in the United States, a 2016 study finds that a reassignment of remittance responsibility up the supply chain is associated with a higher level of economic incidence on consumers, indicating that evasion is more costly with fewer tax remitters.[20] Policymakers should keep this in mind when considering the assignment of remittance responsibility. Additionally, while the economic burden of taxes remitted by businesses may fall on workers or consumers, businesses do typically bear the compliance costs of collecting and remitting these taxes themselves. These costs are significant but are generally excluded in most economic impact analyses of business taxes.[21]

Taxes Paid by Businesses in OECD and EU countries

Using OECD tax revenue data, we compiled different revenue streams into three categories shown in Table 2: business legal tax liability, taxes remitted by business, and non-business tax collection and unallocated revenue.

Table 2. Business and Non-Business Sources of Revenue in OECD and EU Countries (% of Total Tax Revenue, 2023)

| Country | Business Legal Tax Liability | Taxes Remitted by Business | Non-Business Remittance & Unallocated Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia* | 37.93% | 49.07% | 13.00% |

| Austria | 41.93% | 48.25% | 9.82% |

| Belgium | 37.25% | 46.41% | 16.34% |

| Bulgaria* | 46.11% | 45.26% | 8.63% |

| Canada | 32.51% | 49.38% | 18.11% |

| Chile | 38.49% | 55.71% | 5.80% |

| Colombia | 41.81% | 38.65% | 19.54% |

| Costa Rica | 31.77% | 24.83% | 43.40% |

| Croatia* | 37.16% | 52.42% | 10.42% |

| Czechia | 54.65% | 38.50% | 6.85% |

| Denmark | 15.05% | 62.18% | 22.77% |

| Estonia | 43.63% | 42.34% | 14.03% |

| Finland | 34.75% | 51.08% | 14.17% |

| France | 42.57% | 41.65% | 15.78% |

| Germany | 40.93% | 52.88% | 6.19% |

| Greece* | 37.62% | 48.33% | 14.05% |

| Hungary | 29.69% | 62.67% | 7.64% |

| Iceland | 16.59% | 52.99% | 30.42% |

| Ireland | 42.39% | 46.19% | 11.42% |

| Israel | 35.83% | 51.38% | 12.79% |

| Italy | 43.30% | 37.23% | 19.47% |

| Japan* | 39.05% | 48.61% | 12.34% |

| Korea | 34.83% | 45.40% | 19.77% |

| Latvia | 36.55% | 55.76% | 7.69% |

| Lithuania | 24.77% | 73.52% | 1.71% |

| Luxembourg | 43.57% | 48.73% | 7.70% |

| Malta* | 35.93% | 56.66% | 7.41% |

| Mexico | 37.48% | 42.22% | 20.30% |

| Netherlands | 40.65% | 48.72% | 10.63% |

| New Zealand | 22.69% | 64.80% | 12.51% |

| Norway | 46.14% | 36.89% | 16.97% |

| Poland* | 52.98% | 38.23% | 8.79% |

| Portugal | 38.85% | 36.67% | 24.48% |

| Romania* | 27.74% | 62.25% | 10.01% |

| Slovak Republic | 50.43% | 39.89% | 9.68% |

| Slovenia | 39.84% | 53.67% | 6.49% |

| Spain | 48.78% | 39.75% | 11.47% |

| Sweden | 37.53% | 45.16% | 17.31% |

| Switzerland | 32.21% | 50.81% | 16.98% |

| Turkey | 39.47% | 32.69% | 27.84% |

| United Kingdom | 32.40% | 53.45% | 14.15% |

| United States | 39.54% | 48.05% | 12.41% |

| Average** | 37.70% | 48.08% | 14.22% |

| OECD Average | 37.80% | 47.44% | 14.76% |

* 2022 data.

**Average of the countries above.

Source: Author’s calculations; see Tax Foundation, “Total Tax Contribution,” GitHub, https://github.com/TaxFoundation/Total-Tax-Contribution.

Countries are quite different in how much they rely on business tax payments, but the typical OECD country receives 37.8 percent of its tax revenues from businesses. Czechia is the most “business-reliant” country with businesses paying 54.65 percent of its total tax collections. Denmark and Iceland could be considered the least business-reliant, with 15.05 percent and 16.59 percent of their total tax collections paid by businesses, respectively. Fifteen countries receive more than 40 percent of their total tax collections from direct payments by business.

Income taxes from corporations and pass-through businesses comprise an average of 13.5 percent of all tax collections for OECD countries. Latvia collects the least amount at 4.18 percent of total collections, while Colombia collects the most at 32.31 percent of total revenues.

Excise taxes are typically considered to be a tax on individual consumers, but OECD countries collect an average of 5.88 percent of their total tax revenues from excise taxes paid by businesses on input purchases. New Zealand and the United States collect the least amount of excise on business inputs at 0.71 percent and 2.49 percent of revenues, respectively. [22] However, the United States collects 6.07 percent of its total tax revenue when accounting for both excise and sales taxes on business inputs. Turkey, Bulgaria, and Croatia collect the most in excise taxes at 15.06 percent, 10.76 percent, and 10.36 percent of total revenues, respectively.

In addition to the corporate income tax, excises, and a small amount of property taxes, in many countries businesses are also paying a growing share of the social security contributions. While these contributions are generally split between the employee and the employer, on average, across OECD countries, employer social security contributions made up 57.84 of all social security contributions and 16.58 percent of the total tax mix in 2023.[23] For the OECD countries analyzed, social security payments by businesses averaged 14.09 percent of total revenues. However, as mentioned in Table 1, business payments for employer social security contributions exclude public employees.

Social security contributions were the largest source of tax revenue in 10 OECD countries—Austria, Costa Rica, Czechia, France, Germany, Japan, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. Unsurprisingly, a number of these countries lead the list of those most dependent upon business tax payments.

As important as the direct contribution of businesses to the total revenue can be, businesses play an even larger role for governments by remitting taxes on behalf of others. As Figure 1 shows, businesses collect and remit an average of 47.44 percent of the total tax revenues in OECD countries. In large measure, this is due to the important role that businesses play in collecting withholding taxes from employees for their income and social security contributions, along with collecting and remitting value-added and sales taxes. Lithuania relies the most on tax remittances by business at 73.52 percent of all tax collections. In New Zealand, businesses remit 64.8 percent of all collections. In 15 countries, including three non-OECD countries—Croatia, Romania, and Malta—businesses remit more than 50 percent of all tax collections. Costa Rica could be considered the least reliant on business remittances, collecting roughly 24.83 percent of all tax revenues from this source.[24]

Overall, on average, businesses are liable for collecting, paying, and remitting more than 85 percent of the total tax collections in OECD countries. In Lithuania, Chile, Germany, Slovenia, and Czechia, businesses pay and remit more than 93 percent of all taxes. Put simply, if all firms closed, these governments would need to find a new way to collect 93 percent of the revenue they receive each year.

While each country may have a different mix of business tax payments and tax remittances, it is clear that public finance systems are heavily reliant on businesses as the primary taxpayer and tax collectors.

Conclusion

On average, in OECD and EU countries, businesses pay more than one-third of all taxes collected; including other taxes remitted and collected, businesses account for more than 85 percent of all revenue collected. These figures highlight the important role firms systematically play in the broader tax system. Moreover, without businesses acting as tax collectors and bearing those compliance costs, governments’ tax collection agencies would need to incur significant additional costs to raise a similar or even lower amount of revenue. Policymakers should add these aspects to their formula when considering “fair share” arguments.

Additionally, due to the economic incidence of taxes, any attempt to increase the tax burden on corporations will inevitably harm workers, shareholders, or customers. The extent of the harm will simply depend upon the type of tax and the economic circumstances in which the tax is levied.

Policymakers should weigh the marginal benefit of generating additional revenues from companies against the economic harm caused by the loss of investment, jobs, and economic growth that businesses facilitate.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeReferences

[1] Tax Justice Network, “Fair taxes are key to a fair share for all,” https://taxjustice.net/2014/10/17/fair-taxes-key-fair-share/.

[2] European Commission, “Fair Taxation of the Digital Economy,” Mar. 21, 2018, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017DC0547.

[3] European Commission, “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, an Action Plan for Fair and Simple Taxation Supporting the Recovery Strategy,” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:0312:FIN.

[4] EBTF and PwC, “Total Tax Contribution: A study of the largest companies headquartered in Europe,” March 2023, https://ebtforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/EBTF-2024-TTC-Report.pdf.

[5] UNCTAD, “World Investment Report 2015: Reforming International Investment Governance,” http://unctad.org/en/PublicationChapters/wir2015ch5_Annex_I_en.pdf.

[6] UNCTAD, “World Investment Report 2015: Reforming International Investment Governance,” http://unctad.org/en/PublicationChapters/wir2015ch5_en.pdf.

[7] UNCTAD, “World Investment Report 2024: Investing in Sustainable Development,” Jun. 20, 2024, https://unctad.org/publication/world-investment-report-2024.

[8] Stephen J. Entin, “Labor Bears Much of the Cost of the Corporate Tax,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 24, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/labor-bears-corporate-tax/.

[9] Eurostat, “Main National Accounts Tax Aggregates,” https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/gov_10a_taxag__custom_15781048/default/table?lang=en.

[10] Eurostat, “Compensation of Employees,” https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tec00013/default/table?lang=en.

[11] R. Alison Felix, “Passing the Burden: Corporate Tax Incidence in Open Economies,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Oct. 21, 2007, https://www.kansascityfed.org/documents/118/regionalrwp-rrwp07-01.pdf.

[12] See: R. Alison Felix, “Do State Corporate Income Taxes Reduce Wages,” Economic Review 94:2 (2009): 77–102, and J.C. Suárez Serrato and O. Zidar, “Who Benefits from State Corporate Tax Cuts? A Local Labor Markets Approach with Heterogeneous Firms,” NBER Working Paper 20289, 2014.

[13] Clemens Fuest, Andreas Peichl, and Sebastian Siegloch, “Do Higher Corporate Taxes Reduce Wages? Micro Evidence from Germany,” American Economic Review (February 2018).

[14] R. Alison Felix and J. R. Hines, “Corporate Taxes and Union Wages in the United States,” NBER Working Paper 15263, 2009.

[15] J.C. Suárez Serrato and O. Zidar, “Who Benefits from State Corporate Tax Cuts? A Local Labor

Markets Approach with Heterogeneous Firms,” NBER Working Paper 20289, 2014.

[16] Michael Abbott, Charles Beach, and Richard Chaykowski, “Transition and Structural Change in the North American Labour Market,” IRC Press, 1997.

[17]Edison Roy-César and François Vaillancourt, “The Incidence of Payroll Taxes in Ontario and Quebec: Evidence

from Collective Agreements for 1985-2007,” CIRANO Scientific Series 36 (Sep. 24, 2010).

[18] Ryan Sullivan and Donald Dutkowsky, “The Effect of Cigarette Taxation on Prices: An Empirical Analysis using City-level Data,” Public Finance Review 40 (October 2012).

[19] Dragana Benedek, Rens de Mooij, Michael Keen, and Peter Wingender, “Estimating VAT Pass Through,” IMF Working Paper 15:214 (2015).

[20] Wojciech B. Kopczuk, Jonathan Marion, Erich Muehlegger, and Joel Slemrod, “Does Tax-Collection Invariance Hold? Evasion and the Pass-through of State Diesel Taxes,” NBER Working Paper 19410, 2016, https://www.nber.org/papers/w19410.

[21] Tax compliance costs represent 29 percent of the total taxes paid and remitted by an average EU company; see KPMG, VVA, Di Legge, A. et al., “Tax compliance costs for SMEs – An update and a complement – Final report,” European Union, 2022, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2873/180570, and William McBride, “Results of a Survey Measuring Business Tax Compliance Costs,” Tax Foundation, Sep. 4, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/us-business-tax-compliance-costs-survey/.

[22] It is worth noticing that the EU minimum excise duty on gasoline (€0.357 per liter) is greater than the highest gas taxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline. in the US, which is approximately €0.19 per liter in California (combining federal and state taxes). See Adam Hoffer, “Diesel and Gas Taxes in Europe, 2024,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 13, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/eu/gas-taxes-in-europe-2024/.

[23] OECD, “Revenue Statistics 2024: Health Taxes in OECD Countries,” 2024, https://doi.org/10.1787/c87a3da5-en.

[24] However, this reduced amount could be due to the 40 percent of total revenue collections that could be allocated between the different remittents.

Share this article