Key Findings

-

Comparisons of capital gains taxA capital gains tax is levied on the profit made from selling an asset and is often in addition to corporate income taxes, frequently resulting in double taxation. These taxes create a bias against saving, leading to a lower level of national income by encouraging present consumption over investment. rates and taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rates on labor income should factor in all the layers of taxes that apply to capital gains.

-

The tax treatment of capital income, such as from capital gains, is often viewed as tax-advantaged. However, capital gains taxes place a double-tax on corporate income, and taxpayers have often paid income taxes on the money that they invest.

-

Capital gains taxes create a bias against saving, which encourages present consumption over saving and leads to a lower level of national income.

-

The tax code is currently biased against saving and investment; increasing the capital gains tax rate would add to the bias against saving and reduce national income.

Introduction

The tax treatment of capital income, such as from capital gains, is often viewed as tax-advantaged. However, viewed in the context of the entire tax system, there is a tax bias against income like capital gains. This is because taxes on saving and investment, like the capital gains tax, represent an additional layer of tax on capital income after the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. and the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. .

Under a neutral tax system, each dollar of income would only be taxed once. Currently, the tax code provides neutral treatment to some forms of saving, such as 401(k)s and Individual Retirement Accounts, but saving and investment activities outside of these arrangements do not receive neutral tax treatment.[1]

Capital gains face multiple layers of tax, and in addition, gains are not adjusted for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. . This means that investors can be taxed on capital gains that accrue due to price-level increases rather than real gains.

Capital gains taxes affect more than just shareholders; there are repercussions across the entire economy. Capital gains taxes can be especially harmful for entrepreneurs, and because they reduce the return to saving, they encourage immediate consumption over saving.

Lawmakers should consider all layers of taxes that apply to capital gains, and other types of saving and investment income, when evaluating their tax treatment. Given the importance of national savings to the economy, raising taxes on saving would be misguided.

This paper will review the tax treatment of capital gains under current law and then discuss reasons for the lower rates as well as economic and revenue considerations for changing capital gains tax rates.

The Structure of Capital Gains Taxes

Capital gains, or losses, refer to the increase, or decrease, in the value of a capital asset between the time it’s purchased and the time it’s sold. Capital assets generally include everything a person owns and uses for personal purposes, pleasure, or investment, including stocks, bonds, homes, cars, jewelry, and art.[2] The purchase price of a capital asset is typically referred to as the asset’s basis. When the asset is sold at a price higher than its basis, it results in a capital gain; when the asset is sold for less than its basis, it results in a capital loss.

In the United States, when a person realizes a capital gain—that is, sells a capital asset for a profit—they face a tax on the gain. Capital gains tax rates vary with respect to two factors: how long the asset was held and the amount of income the taxpayer earns.

If an asset was held for less than one year and then sold for a profit, it is classified as a short-term capital gain and taxed as ordinary income. If an asset was held for more than one year and then sold for a profit, it is classified as a long-term capital gain. Table 1 illustrates the tax rates applicable to long-term capital gains for tax year 2019.[3] The income thresholds for long-term capital gains tax rates are indexed to inflation. However, the thresholds for the 3.8 percent net investment income tax (NIIT), an additional tax that applies to long-term capital gains, are not. Additionally, the NIIT also applies to short-term capital gains.

|

Source: “2019 Tax Brackets,” Tax Foundation and IRS Topic Number 559 |

||||

| For Unmarried Individuals | For Married Individuals Filing Joint Returns | For Heads of Households | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxable Income Over | ||||

| 0% | $0 | $0 | $0 | |

| 15% | $39,375 | $78,750 | $52,750 | |

| 20% | $434,550 | $488,850 | $461,700 | |

| Additional Net Investment Income Tax | ||||

| 3.8% | MAGI above $200,000 | MAGI above $250,000 | MAGI above $200,000 | |

In addition to federal taxes on capital gains, most states levy income taxes that apply to capital gains. At the state level, income taxes on capital gains vary from 0 percent to 13.3 percent.[4] This means long-term capital gains in the United States can face up to a top marginal rate of 37.1 percent.

If an asset is sold for less than its basis, resulting in a capital loss, taxpayers may use that loss to offset capital gains. If capital losses are more than capital gains, taxpayers can deduct the difference on their tax return to offset up to $3,000 of taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. per year, or $1,500 if married filing separately.[5] If the total amount of the net capital loss is greater than the limit, it can be carried over to the next year’s tax return.[6]

Owner-occupied Housing Exclusion

Currently, the tax code provides an exemption for capital gains associated with the sale of owner-occupied homes.[7] Single filers may exclude up to $250,000 and married filers up to $500,000 if the filers had lived in the home for at least two of the previous five years. The exemption may be taken only once every two years.

This exclusion extends neutral tax treatment to a portion of capital gains but does not do so equally for all taxpayers. As a previous Tax Foundation report explained:

A fixed exempt amount protects a fixed amount of gains, regardless of the amount of the sale price that is due to inflation. The exemption might overcompensate or under-compensate for the inflation portion of the gain, and is therefore an imperfect offset to inflation, if that is the intent. However, it does extend saving-consumption neutral tax treatment to the investment in the home. In effect, the house is bought with after-tax incomeAfter-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. , and the annual shelter service provided by the home and the sales price are untaxed returns, as in a Roth IRA. For people who move often enough, the current policy shelters more of the gains in a home than would be covered by indexing. People who remain in one home for many decades or who bought high-priced homes on which subsequent price gains are large in dollar terms may find that they have gains greater than the exempt amounts. These homeowners would benefit from additional indexing of the initial cost basis and any improvements made over the years.[8]

Capital Gains in Estates

A policy called step-up in basisThe step-up in basis provision adjusts the value, or “cost basis,” of an inherited asset (stocks, bonds, real estate, etc.) when it is passed on, after death. This eliminates the capital gains tax owed by the recipient, reducing the heir’s tax liability. The cost basis receives a “step-up” to its fair market value, or the price at which the good would be sold or purchased in a fair market. reduces capital gains tax liability on property that is passed to an heir. When a person leaves property to an heir, the cost basis of the asset receives a “step-up” in basis to reflect its fair market value at the time of the original owner’s death, which excludes any increase in value that occurred during the original owner’s lifetime from the capital gains tax.[9]

This policy discourages taxpayers from realizing capital gains, instead incentivizing them to hold capital gains until death. This policy, considered a tax expenditureTax expenditures are departures from a “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. However, defining which tax expenditures grant special benefits to certain groups of people or types of economic activity is not always straightforward. , allows taxpayers to entirely exclude returns on saving from the capital gains tax. However, step-up in basis also prevents the double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. that would occur if heirs owed both capital gains taxes and estate taxes on the same asset. Ending step-up in basis without also making reforms to the capital gains tax would increase the cost of capital and subject these returns to saving to multiple layers of tax.[10]

Should Capital Gains be Taxed Differently?

Comparisons are often made between the long-term capital gains tax rates and the tax rates that apply to ordinary income, with the call to equalize the two rates. However, several factors, discussed below, lead to a different conclusion.

A Double Tax on Corporate Income

Currently, the top marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. on ordinary income is 37 percent, while the top marginal rate on long-term capital gains is 23.8 percent. However, the capital gains tax should be thought of as a double tax; thus, one justification for the lower rate is that capital gains income is earned in an environment where other taxes have already been applied.[11]

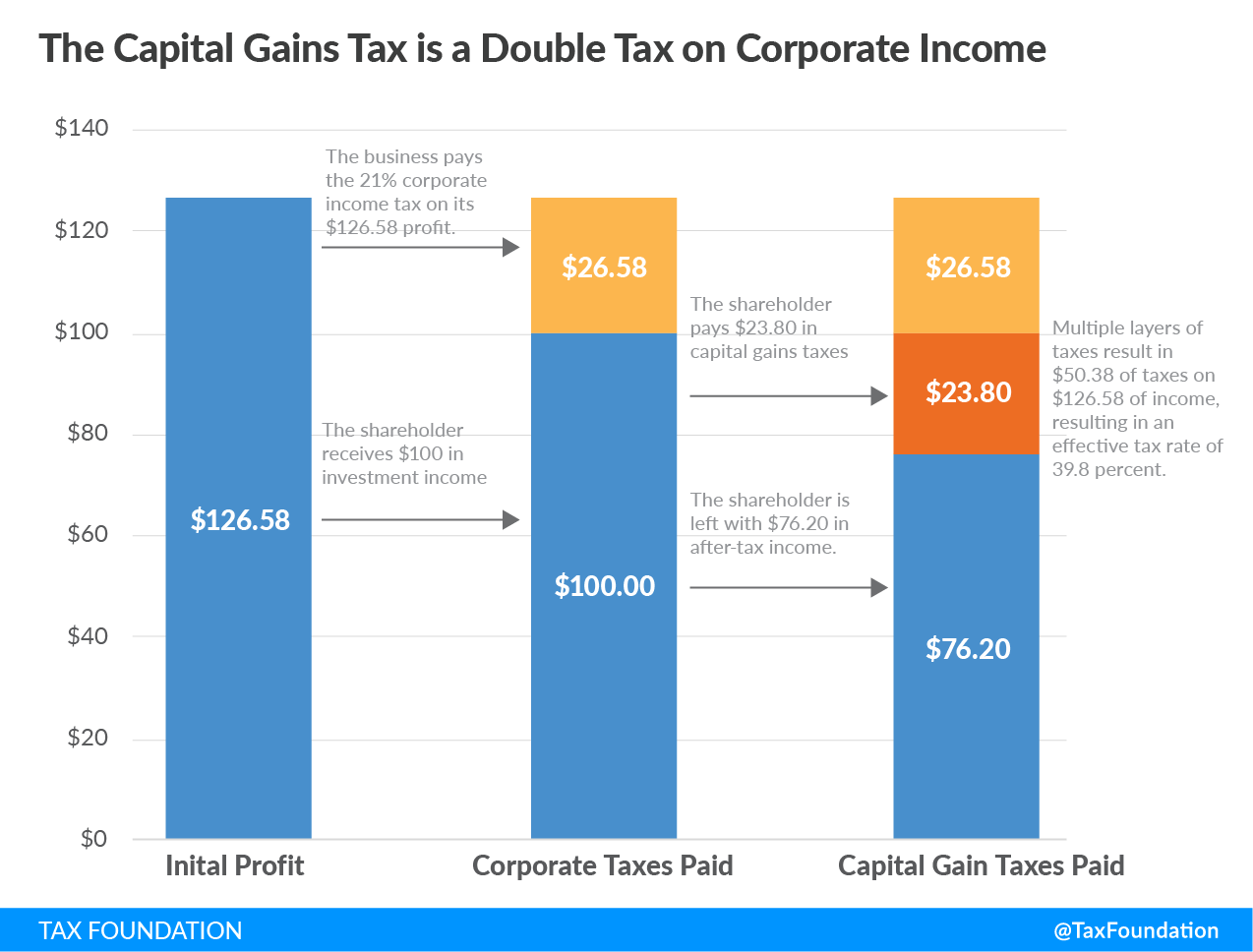

The taxation of capital gains places a double tax on corporate income. Before shareholders face taxes, the business first faces the corporate income tax. A business pays the 21 percent corporate income tax on its profits; thus, when the shareholder pays their layer of tax they are doing so on dividends or capital gains distributed from after-tax profits.

Suppose that a taxpayer in the top tax bracket receives $100 of investment income. Such taxpayer would owe $23.80 in taxes on that investment income. But it can be easy to miss that the $100 in investment income had already been taxed at the corporate level—that $100 started out as $126.58 for the corporation, subject to the 21 percent corporate tax rate.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeThe corporation paid $26.58 in federal taxes on behalf of the investor, and the remaining $100 was passed on to the shareholder and taxed again. This results in a total of $50.38 of taxes on $126.58 of income, or an actual tax rate of 39.8 percent.

In addition to corporate income taxes, it is typical that before an individual invests her money, she has already paid ordinary income taxes on it. This reduces the amount of money a taxpayer has to invest, thus implicitly subjecting the investment to federal taxes. Taxing capital gains creates an additional tax to the taxes on wages and business income.[12] But because individuals can delay realization of capital gains, this does lower the effective tax rate they face because delaying reduces the present value of the tax burden.[13]

Inflated Value of Capital Assets

As mentioned previously, capital gains taxes are owed when a capital asset is sold for a price higher than its basis. Under the current tax system, capital gains are not adjusted for inflation, meaning individuals pay tax on income plus any capital gain that results from price-level increases.[14] Inflationary gains do not represent a real increase in wealth, thus taxes on inflationary gains are taxes on “fictitious” income, which increases the effective tax rate on saving and investment.

In a previous Tax Foundation report, “Inflation Can Cause an Infinite Effective Tax Rate on Capital Gains,” the following example is used to illustrate the problem caused by not adjusting capital gains for inflation:

When an individual buys a stock and later sells it for a capital gain, they must pay tax on this income. For instance, suppose an individual purchased an average stock valued at $7.51 in 1980 and sells this stock in 2013 for $100.[15] As a result, he realized a capital gain of $92.49 and must pay the 23.8 percent tax[16] of $22.01 on this nominal gain. However, since there was inflation during this period, the real gain was actually only $78.79. This implies that the taxpayer paid an effective rate of 27.9 percent on the real gain.[17]

In other cases, inflation can account for 100 percent of the capital gains tax owed; further, inflation can cause a nominal gain to be realized despite suffering a capital loss in real terms.[18] Ultimately, the lower rate on capital gains does not mitigate the inflation issue, as taxpayers still face tax liability whether they made a real gain or real loss.

Economic and Revenue Considerations

The capital gains tax creates a bias against saving. When multiple layers of tax apply to the same dollar, as is the case with capital gains, it distorts the choice between immediate consumption and saving, skewing it towards immediate consumption because the multiple layers reduce after-tax return to saving.

Suppose a person makes $1,000 and pays individual income taxes on that income. The person now faces a choice: should I save my after-tax money or should I spend it? Spending it today on a good or service would likely result in paying some state or local sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. . However, saving it would mean paying an additional layer of tax, such as the capital gains tax, plus the sales tax when the money is eventually used to purchase a good or service. This second layer of tax reduces the potential return that a saver can earn on their savings, thus skewing the decision toward immediate consumption rather than saving. By immediately spending the money, the second layer of tax can be avoided.

As a whole, America does not save enough to fund its domestic investments; foreign saving makes up the difference.[19] In the United States, investment outpaces saving because foreign savers fund the investments that American savers cannot afford. If the return to saving for U.S. savers decreased, U.S. saving would fall and foreign savers would provide additional funds, all else equal. This would result in less ownership of U.S. assets by U.S. savers and a decrease in national income. Conversely, an increase in saving by U.S. savers would boost national income.

Consequences for Entrepreneurial Activity

An analysis of Federal Reserve data done by William M. Gentry indicates that entrepreneurial assets comprise a larger share of aggregate household portfolios than the taxable holdings of corporate equities.[20] In other words, there is a relatively large stock of unrealized capital gains associated with entrepreneurial ventures compared to corporate equities—entrepreneurial assets comprise nearly 17 percent of overall household portfolios.[21]

Entrepreneurship involves taking risk; but many of these risky investments are not successful, and those that are often begin by running losses for a period before becoming profitable.[22] Because the capital gains tax is a tax in addition to those on wage and business income, the capital gains tax is an asymmetric tax on successful entrepreneurial ventures.[23] Further, the capital gains tax is asymmetric in that it immediately taxes gains, while capital losses do not immediately result in a tax benefit.[24]

The capital gains tax is not neutral. Research shows that capital gains taxes can affect the decision to start a business, how and when entrepreneurs exit their business, and the ability to raise funds from outside investors.[25]

Realization Effect

Capital gains, and dividend income, comprise a relatively small share of individual income, meaning rate changes have a relatively small effect on total revenue raised by the individual income tax. For example, in 2016, capital gains accounted for just 8.4 percent of income reported on tax returns, meaning capital gains are a small portion of the individual income tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. .[26] Additionally, because of the realization effect, increases in the capital gains rate can lead to immediate reductions in revenue.[27]

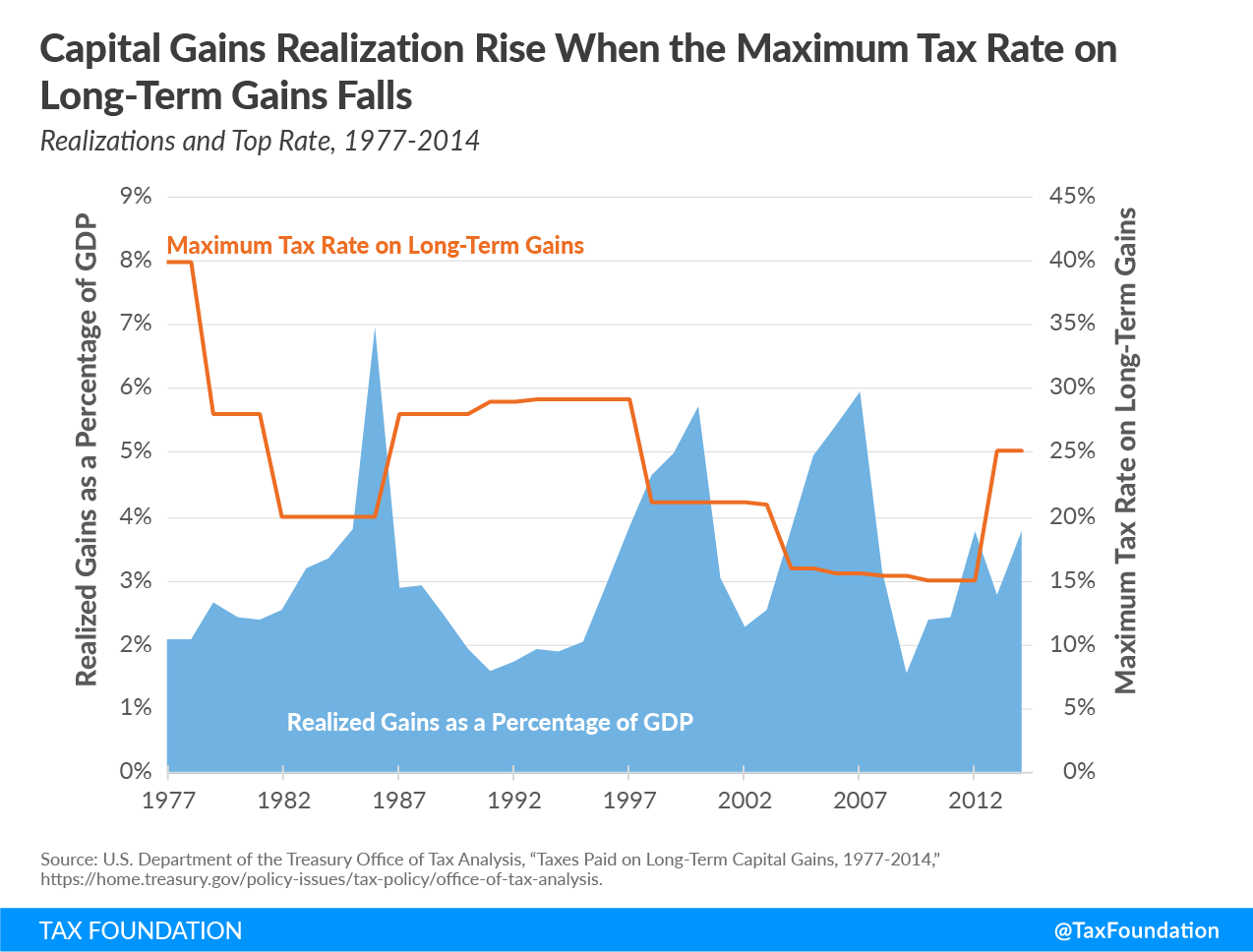

Because capital gains are only taxed when realized, taxpayers get to choose when they pay their capital gains taxes, which makes them significantly more responsive to tax changes than other types of income.[28] Higher tax rates on capital gains cause investors to sell their assets less frequently, which leads to less taxes being assessed, known as the realization or lock-in effect.[29] This relationship between capital gains tax rates and realized capital gains is demonstrated in the chart below.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeHowever, proposals such as mark-to-market would make the realization effect a non-issue. This is because under mark-to-market, yearly gains associated with assets would be taxed regardless of whether owners realize the gains. Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Ron Wyden (D-OR) announced that he is developing a mark-to-market proposal to tax annual gains on assets owned by millionaires and billionaires.[30]

Conclusion

A neutral tax code would tax each dollar of income only once. Capital gains taxes create a burden on saving because they are an additional layer of taxes on a given dollar of income. The capital gains tax rate cannot be directly compared to individual income tax rates, because the additional layers of tax that apply to capital gains income must also be part of the discussion.

Increasing taxes on capital income would further the tax bias against saving, discouraging Americans from saving and leading to a decrease in national income.

Notes

[1] Erica York, “The Complicated Taxation of America’s Retirement Accounts,” Tax Foundation, May 22, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/retirement-accounts-taxation/.

[2] Internal Revenue Service, Publication 550.

[3] There are other rules for certain types of capital gains. For example, net capital gains that result from selling collectibles such as coins or art are taxed at a maximum rate of 28 percent. See Internal Revenue Service, “Topic Number 409 – Capital Gains and Losses,” https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc409.

[4] Jared Walczak, Scott Drenkard, and Joseph Bishop-Henchman, 2019 State Business Tax Climate Index, Tax Foundation, Sept. 26, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/state-business-tax-climate-index/.

[5] Internal Revenue Service, “Helpful Facts to Know About Capital Gains and Losses,” https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/helpful-facts-to-know-about-capital-gains-and-losses.

[6] Ibid.

[7] See Stephen J. Entin, “Getting ‘Real’ by Indexing Capital Gains for Inflation,” Tax Foundation, March 6, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/inflation-adjusting-capital-gains/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Scott Eastman, “The Trade-offs of Repealing Step-Up in Basis,” Tax Foundation, March 13, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/step-up-in-basis/.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Tax Foundation, Options for Reforming America’s Tax Code, June 6, 2016, 26, /wp-content/uploads/2016/06/TF_Options_for_Reforming_Americas_Tax_Code.pdf.

[12] William M. Gentry, “Capital Gains Taxation and Entrepreneurship,” American Council for Capital Formation Center for Policy Research, March 2016, 23, https://www.law.upenn.edu/live/files/5474-capital-gains-taxation-and-entrepreneurship-march.

[13] See Kyle Pomerleau, “Economic and Budgetary Impact of Indexing Capital Gains to Inflation,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 4, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/economic-budget-impact-indexing-capital-gains-inflation/.

[14] Kyle Pomerleau, “How One Can Face an Infinite Effective Tax Rate on Capital Gains,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 7, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/how-one-can-face-infinite-effective-tax-rate-capital-gains/.

[15] This assumes the stock grew at the same rate as the S&P 500 during that 10-year period.

[16] As of January 1, 2013, the top tax rate on capital gains was 23.8 percent. This hypothetical assumes that the taxpayer’s AGI exceeds $200,000.

[17] The effective rate is found by dividing the tax of $22.01 by the real gain of $78.79.

[18] Kyle Pomerleau, “Inflation Can Cause an Infinite Effective Tax Rate on Capital Gains.”

[19] Alan Cole, “Losing the Future: The Decline of U.S. Saving and Investment,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 1, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/losing-future-decline-us-saving-and-investment.

[20] Kyle Pomerleau, “Economic and Budgetary Impact of Indexing Capital Gains to Inflation, 4.

[21] Ibid, 9.

[22] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Entrepreneurship and the U.S. Economy,” https://www.bls.gov/bdm/entrepreneurship/bdm_chart3.htm.

[23] William M. Gentry, “Capital Gains Taxation and Entrepreneurship,” 25.

[24] Kyle Pomerleau, “Testimony: The Tax Code as a Barrier to Entrepreneurship,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 15, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-code-barrier-entrepreneurship/.

[25] Ibid, 26.

[26] Robert Bellafiore, “Sources of Personal Income 2016 Update,” Sept. 11, 2018, Tax Foundation, https://taxfoundation.org/sources-of-personal-income-2016/.

[27] See Proposal 2 in Kyle Pomerleau and Huaqun Li, “How Much Revenue Would a 70% Top Tax Rate Raise? An Initial Analysis,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 14, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/70-tax/.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Michael Schuyler, “The Effects of Terminating Tax Expenditures and Cutting Individual Income Tax Rates,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 30, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/effects-terminating-tax-expenditures-and-cutting-individual-income-tax-rates/.

[30] United States Senate Committee of Finance, “Wyden to Unveil Plan to Ensure Wealthy Pay Their Fair Share,” April 2, 2019, https://www.finance.senate.gov/ranking-members-news/wyden-to-unveil-plan-to-ensure-wealthy-pay-their-fair-share-.

Share this article