Related Research

Key Findings

- One of the most significant provisions of the TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Cuts and Jobs Act is the permanently lower federal corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate, which decreased from 35 percent to 21 percent.

- Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the United States’ high statutory corporate tax rate stood out among rates worldwide. Among countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the U.S. combined corporate income tax rate was the highest. Now, post-tax reform, the rate is close to average.

- A corporate income tax rate closer to that of other nations will discourage profit shiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens. to lower-tax jurisdictions.

- New investment will increase the size of the capital stock, and productivity, output, wages, and employment will grow. The Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth model estimates that the total effect of the new tax law will be a 1.7 percent larger economy, leading to 1.5 percent higher wages, a 4.8 percent larger capital stock, and 339,000 additional full-time equivalent jobs in the long run.

- Economic evidence suggests that corporate income taxes are the most harmful type of tax and that workers bear a portion of the burden. Reducing the corporate income tax will benefit workers as new investments boost productivity and lead to wage growth.

- If lawmakers raised the corporate income tax rate from 21 percent to 25 percent, we estimate the tax increase would shrink the long-run size of the economy by 0.87 percent, or $228 billion. This would reduce the capital stock by 2.11 percent, wages by 0.74 percent, and lead to 175,700 fewer full time equivalent jobs.

Introduction

Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States corporate income tax was widely regarded as uncompetitive for three main reasons: cost recovery, worldwide application, and a high statutory rate. Lawmakers made significant changes to each of these factors in the new tax law enacted in December 2017. The long-run positive effects expected from the TCJA–increases in investment, output, and wages–are entirely due to the reduction in the corporate tax rate, because other pro-growth provisions are scheduled to expire.

Before the TCJA, the United States had the highest combined statutory corporate income tax rate among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, at 38.9 percent (federal plus the average of state corporate income tax rates). The TCJA reduced the federal corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, dropping the U.S. combined rate from 38.9 percent to 25.7 percent and placing the U.S. nearer to the OECD average.

A permanently lower federal corporate income tax rate will lead to several positive economic effects. The benefits of a lower rate include encouraging investment in the United States and discouraging profit shifting. As additional investment grows the capital stock, the demand for labor to work with the new capital will increase, leading to higher productivity, output, employment, and wages over time.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeWhy Does the Corporate Tax Rate Matter?

Under a neoclassical economic view, the main drivers of economic output are the willingness of people to work more and to deploy capital—such as machines, equipment, factories, etc.[1] Taxes play a role in these decisions; specifically, the corporate income tax rate is an important determinant in how much people are willing to invest in new capital, and in where they will place that new capital.

Evidence shows that of the different types of taxes, the corporate income tax is the most harmful for economic growth.[2] One key reason that capital is so sensitive to taxation is because capital is highly mobile. For example, it is relatively easy for a company to move its operations or choose to locate its next investment in a lower-tax jurisdiction, but it is more difficult for a worker to move his or her family to get a lower tax bill. This means capital is very responsive to tax changes; lowering the corporate income tax rate reduces the amount of economic harm it causes.

A common misunderstanding is that corporations bear the cost of the corporate income tax. However, a growing body of economic literature indicates that the true burden of the corporate income is split between workers through lower wages and owners of the corporation.[3] As capital moves away in response to high statutory corporate income tax rates, productivity and wages for the relatively immobile workers fall. Empirical studies show that labor bears between 50 and 100 percent of the burden of the corporate income tax.[4] In the long run, it is split evenly by both capital and labor.[5]

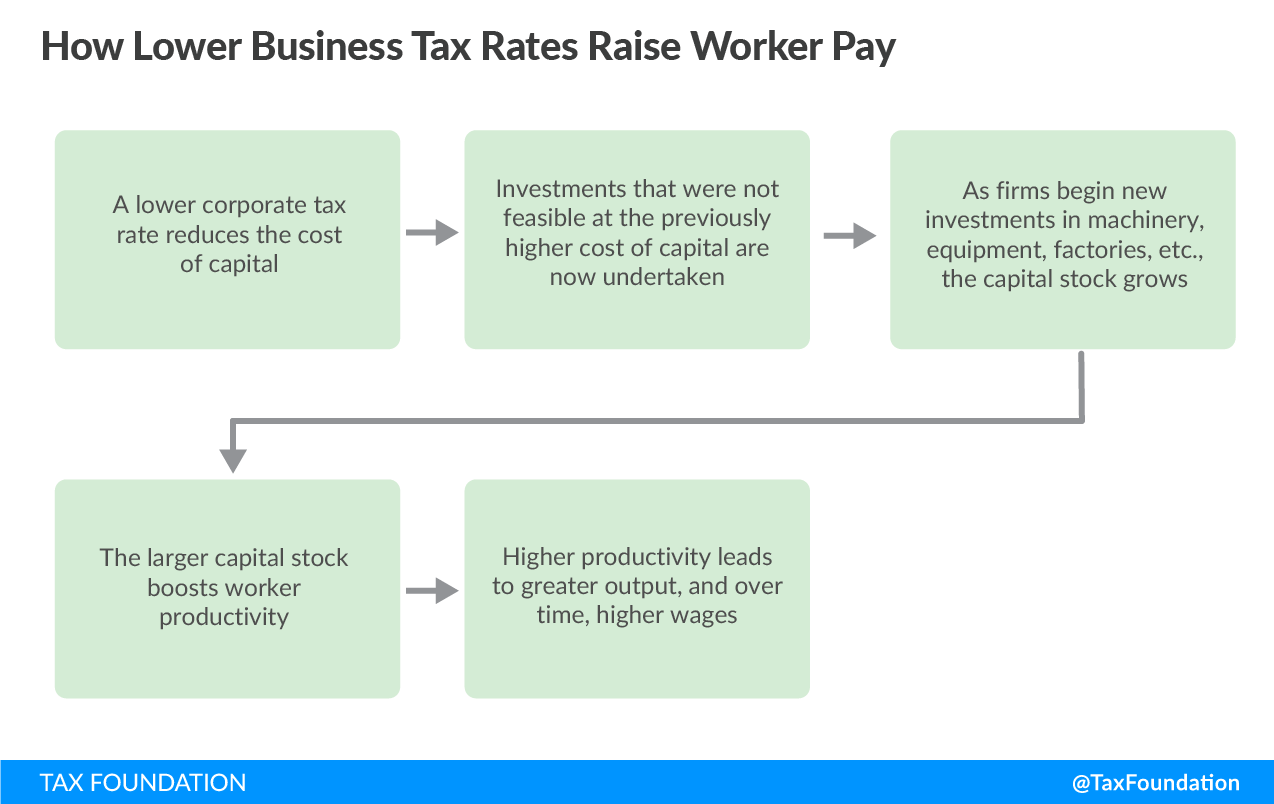

To understand why the lower corporate tax rate drives growth in capital stock, wages, jobs, and the overall size of the economy, it is important to understand how the corporate income tax rate affects economic decisions. When firms think about making an investment in a new capital good, like a piece of equipment, they add up all the costs of doing so, including taxes, and weigh those costs against the expected revenue the capital will generate.

The higher the tax, the higher the cost of capital, the less capital that can be created and employed.[6] So, a higher corporate income tax rate reduces the long-run capital stock and reduces the long-run size of the economy.[7] Conversely, lowering the corporate income tax incentivizes new investment, leading to an increase of the capital stock.

Capital formation, which results from investment, is the major force for raising incomes across the board.[8] More capital for workers boosts productivity, and productivity is a large determinant of wages and other forms of compensation. This happens because, as businesses invest in additional capital, the demand for labor to work with the capital rises, and wages rise too.[9] It is because of these economic effects that, of all the permanent elements considered during the tax reform debates, reducing the corporate tax rate was the most pro-growth.[10]

Corporate Tax Rates around the World

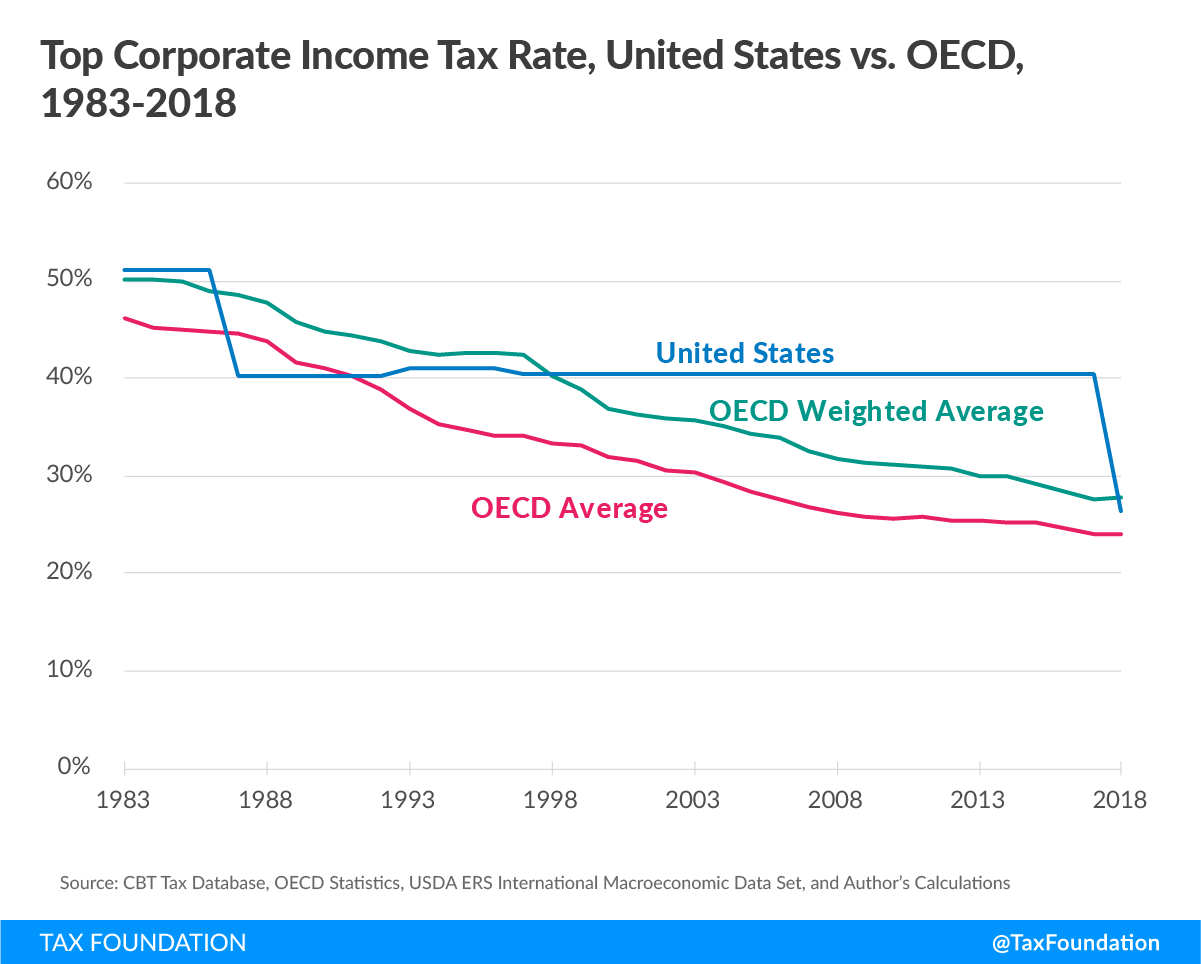

The last time the United States reduced the federal corporate income tax was in 1986, but since then, countries throughout the world significantly reduced their statutory rates. From 1980 to 2017, the worldwide corporate tax rate declined from an average of 38 percent to about 23 percent.[11] Over this period, the United States maintained a comparatively high, and uncompetitive, corporate income tax rate.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeOf 202 jurisdictions surveyed in 2017, the United States had the fourth highest statutory corporate income tax rate.[12] And among OECD nations, the United States had the highest combined statutory corporate income tax rate at 38.9 percent.[13] This was approximately 15 percentage points higher than the OECD average, excluding the United States at 23.8 percent.

Tax rate differences, such as that between the United States and other OECD countries, create incentives for firms to earn more income in low-tax jurisdictions and less income in higher-tax jurisdictions.[14] Because the United States had a corporate income tax rate that was much higher than the norm, the U.S. was especially susceptible to base erosion through profit shifting.[15] Thus the United States needed a corporate tax rate that was closer to the norm in order to reduce the incentive for firms to shift profits or physical capital and jobs to lower-tax jurisdictions.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Improved the Corporate Income Tax

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reduced the federal corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, dropping the U.S. combined rate from 38.9 percent to 25.7 percent. This puts the United States slightly above the OECD average of 24 percent, but slightly below the average weighted by GDP.

According to the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Model, the combined effect of all the changes in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act will increase the long-run size of the U.S. economy by 1.7 percent.[16] The larger economy would result in 1.5 percent higher wages, a 4.8 percent larger capital stock, and 339,000 additional full-time equivalent jobs in the long run.

|

Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, November 2017. |

|

| Change in long-run GDP | 1.7% |

| Change in long-run capital stock | 4.8% |

| Change in long-run wage rate | 1.5% |

| Change in long-run full-time equivalent jobs | 339,000 |

The reduction in the corporate tax rate drives these long-run economic benefits by significantly lowering the cost of capital.

| Provision | Long-run GDP Growth | |

|---|---|---|

|

Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, November 2017. Note: This long-run GDP growth figure is larger than the 1.7 percent of total growth from the plan because several other provisions have negative growth effects. A full list of economic effects by provisions is found in Table 5 of Preliminary Details and Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. |

||

| Lower the corporate income tax rate to 21 percent | 2.6% | |

The TCJA Encourages Other Countries to Have More Competitive Tax Structures

The international corporate tax landscape has changed over the past several decades, as noted above, and the average statutory rates in all regions saw a net decline between 1980 and 2017.[17] Once the highest rate in the OECD, the United States corporate income tax rate is now closer to the middle of the pack. This will encourage other countries to move away from high taxes on capital toward more competitive corporate income tax rates.

The increase in the U.S.’s competitiveness implies a relative reduction in the competitiveness of other nations. For example, a recent report from the International Monetary Fund recommends to Canada: “It is time for a careful rethink of corporate taxation to improve efficiency and preserve Canada’s position in a rapidly changing international tax environment.”[18] The report also notes that the U.S. tax reform increased the urgency of this needed review.

This recommendation has been echoed in other countries. For example, lawmakers in Australia are considering reducing their corporate income tax rate by 5 percentage points to 25 percent, reportedly because “the need to reduce the tax burden on businesses had become more pressing for future Australian jobs and investment since the 2016 election because the United States had reduced its top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent.”[19] The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act improved the global competitiveness of the United States in attracting new investment, and other countries are likely to respond with further improvements in their tax systems.

Raising the Corporate Income Tax Rate Would Damage Economic Output

It is important for lawmakers to recognize and understand the economic benefits of a globally competitive corporate tax rate, and the trade-offs that increasing the rate would entail. A corporate tax rate that is more in line with our competitors reduces the incentives for firms to realize their profits in lower-tax jurisdictions and encourages companies to invest in the United States. Raising the corporate income tax rate would dismantle the most significant pro-growth provision in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and carry significant economic consequences.

The table below considers the economic effects of raising the corporate tax rate to 22 and 25 percent from the current baseline of 21 percent. Raising the corporate income tax rate would reduce economic growth, and lead to a smaller capital stock, lower wage growth, and reduced employment.

| 22% CIT | 25% CIT | |

|---|---|---|

|

Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, June 2018 |

||

| Change in GDP | -0.21% | -0.87% |

| Change in GDP (billions of 2018 $) | -$56.43 | -$228.11 |

| Change in private capital stock | -0.52% | -2.11% |

| Change in wage rate | -0.18% | -0.74% |

| Change in full-time equivalent jobs | -44,500 | -175,700 |

For example, permanently raising the corporate rate by 1 percent to 22 percent would reduce long-run GDP by over $56 billion; the smaller economy would result in a 0.5 percent decrease in capital stock, 0.18 percent decrease in wages, and 44,500 fewer full-time equivalent jobs. Raising the rate to 25 percent would reduce GDP by more than $220 billion and result in 175,700 fewer jobs.

Raising the corporate tax rate increases the cost of making investments in the United States. Under a higher tax rate, some investments wouldn’t be made, which leads to less capital formation, and fewer jobs with lower wages.

Conclusion

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reduced the federal corporate income tax rate from 35 percent, the highest statutory rate in the developed world, to a more globally competitive 21 percent. This significant change is what drives the projected economic effects of the TCJA, which include increased investment, employment, wages, and output.

Given the positive economic effects of a lower corporate tax rate, lawmakers should avoid viewing the corporate income tax as a potential source of raising additional revenue. Raising the corporate tax rate would walk back one of the most significant pro-growth provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and reduce the global competitiveness of the United States. Economic evidence indicates that it is workers who bear the final burden of the corporate income tax, and that corporate income taxes are the most harmful for economic growth—raising this tax rate is not advisable.

The new, permanently lowered corporate tax rate makes the United States a more attractive place for companies to locate investments and will discourage profit shifting to low-tax jurisdictions. The lower rate incentives new investments that will increase productivity, and lead to higher levels of output, employment, and income in the long run. By permanently lowering the corporate tax rate in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, lawmakers succeeded in making the United States a more globally competitive location for new investment, jobs, innovation, and growth.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNotes

[1] Scott A. Hodge, “Dynamic ScoringDynamic scoring estimates the effect of tax changes on key economic factors, such as jobs, wages, investment, federal revenue, and GDP. It is a tool policymakers can use to differentiate between tax changes that look similar using conventional scoring but have vastly different effects on economic growth. Made Simple,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 11, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/dynamic-scoring-made-simple/.

[2] Asa Johansson, Christopher Heady, Jens Arnold, Bert Brys, and Laura Vartia, “Tax and Economic Growth,” OECD, July 11, 2008, https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/41000592.pdf. See also William McBride, “What Is the Evidence on Taxes and Growth,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 18, 2012, https://taxfoundation.org/what-evidence-taxes-and-growth.

[3] Scott A. Hodge, “The Corporate Income Tax is Most Harmful for Growth and Wages,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 15, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/corporate-income-tax-most-harmful-growth-and-wages/.

[4] Stephen Entin, “Labor Bears Much of the Cost of the Corporate Tax,” Tax Foundation, October, 2017, /wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Tax-Foundation-SR2381.pdf.

[5] Huaqun Li and Kyle Pomerleau, “The Distributional Impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act over the Next Decade,” Tax Foundation, June 28, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/the-distributional-impact-of-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-over-the-next-decade/.

[6] Stephen J. Entin, “Disentangling CAP Arguments against Tax Cuts for Capital Formation: Part 2,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 17, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/disentangling-cap-arguments-against-tax-cuts-capital-formation-part-2.

[7] Alan Cole, “Fixing the Corporate Income Tax,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 4, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/fixing-corporate-income-tax.

[8] Stephen J. Entin, “Disentangling CAP Arguments against Tax Cuts for Capital Formation: Part 2.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Scott A. Hodge, “Ranking the Growth-Producing Tax Provisions in the House and Senate Bills,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 11, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/ranking-growth-producing-tax-provisions-house-senate-bills/.

[11] Kari Jahnsen and Kyle Pomerleau, “Corporate Income Tax Rates around the World, 2017,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 7, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/corporate-income-tax-rates-around-the-world-2017/.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Kyle Pomerleau, “The United States’ Corporate Income Tax Rate is Now More in Line with Those Levied by Other Major Nations,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 12, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/us-corporate-income-tax-more-competitive/.

[14] Erik Cederwall, “Making Sense of Profit Shifting: Kimberly Clausing,” Tax Foundation, May 12, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/making-sense-profit-shifting-kimberly-clausing.

[15] Alan Cole, “Fixing the Corporate Income Tax.”

[16] Tax Foundation staff, “Preliminary Details and Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Dec. 18, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/final-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-details-analysis/.

[17] Kari Jahnsen and Kyle Pomerleau, “Corporate Income Tax Rates around the World, 2017.”

[18] International Monetary Fund, “CANADA: Staff Concluding Statement of the 2018 Article IV Mission,” June 4, 2018, http://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2018/06/04/ms060418-canada-staff-concluding-statement-of-the-2018-article-iv-mission.

[19] Rod McGuirk, “Australia Senate to vote in June on corporate tax cuts,” Fox Business, May 28, 2018, https://www.foxbusiness.com/markets/australian-senate-to-vote-in-june-on-corporate-tax-cuts.

Share this article