What is likely to get lost in the last-minute horse trading between House and Senate conferees as they feverishly work to reconcile differences between their respective tax plans is the primary objective of taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reform—economic growth. While each provision being discussed may have a strong political constituency behind it, some provisions generate more economic growth than others. As conferees weigh which provisions to include in the final bill and which don’t make the cut, the determining factor should be how much GDP growth each provision generates.

Tax Foundation economists used our Taxes and Growth (TAG) Macroeconomic Tax Model to model both the House and Senate plans as they were introduced. While a few of the provisions in each bill changed during markup or during floor debate, these scores should, nonetheless, give conferees guidance on which provisions are more pro-growth and which do little for growth.[i] Conferees should be careful about trading away the most pro-growth elements for those that are politically popular but do little for growth.

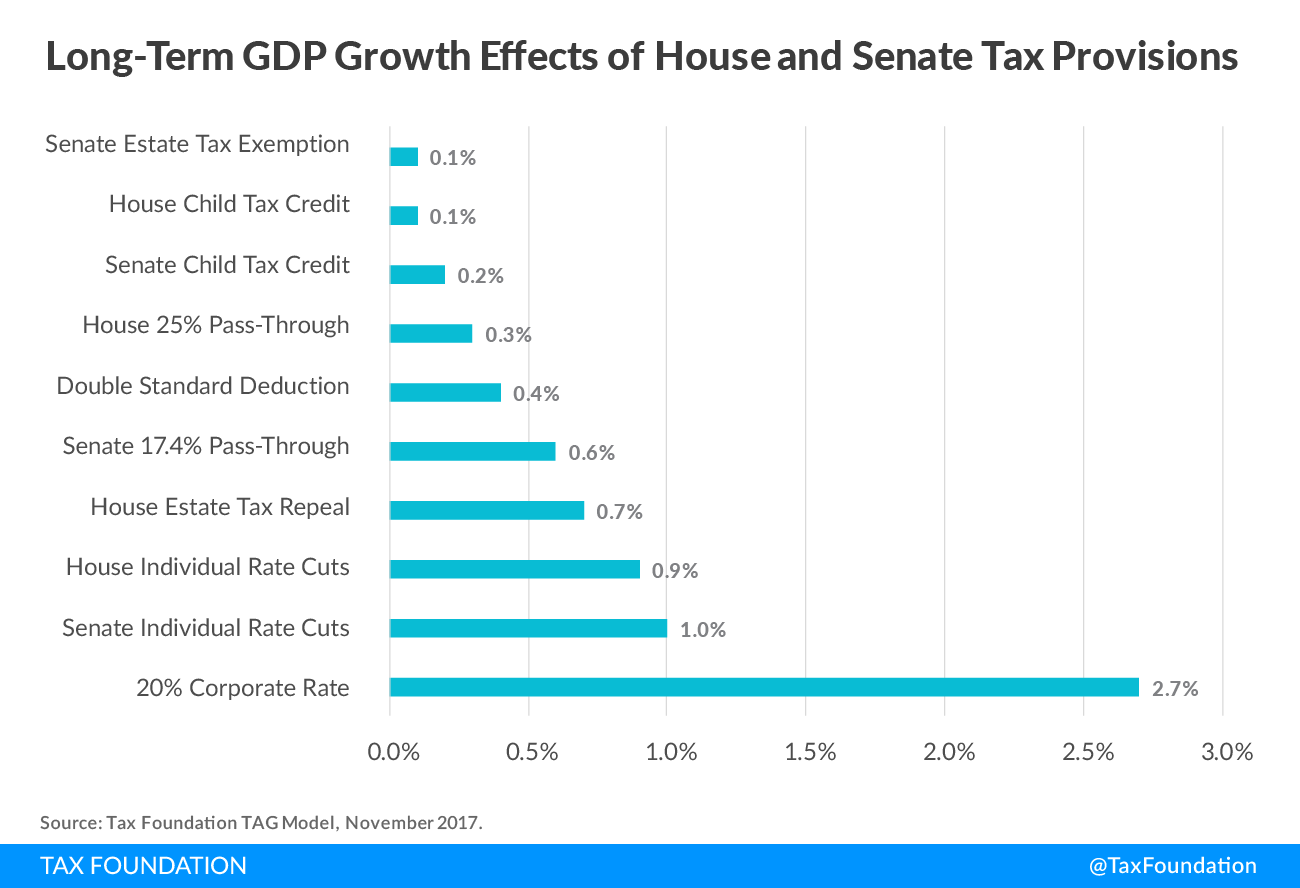

The chart below illustrates the main provisions of each bill that generate at least some economic growth over the ten-year budget window. Missing from the list is the temporary full expensing provision that expires after five years in each of the original bills, although it was phased out in the Senate-passed bill. Were the expensing provision made permanent, it would rank above all those listed below. However, while the temporary nature of the provision does generate short-term economic growth, that dissipates by the end of the budget window after it sunsets.

Here are the ten major pro-growth provisions that conferees must choose from, in order:

#1 Corporate Rate Cut

The most pro-growth element in each of the bills is the reduction in the corporate tax rate to 20 percent. Although the Senate bill delayed implementation of the bill by one year, to 2019, each has the same long-term effect. We estimate that a 20 percent corporate tax rate would boost the size of the economy by 2.7 percent in the long run. While not shown here, the corporate rate cut also creates the most jobs of all the provisions, 530,000, and boosts after-tax incomes by 3.1 percent.

#2 Senate and #3 House Individual Rate Cuts

The individual rate changes are the second-most pro-growth elements in each plan. The Senate plan kept the current seven-bracket format, but reduced each rate and widened some of the brackets. The lower individual tax rates would incentivize people to work more, save more, and draw those out of work into the workforce. We estimate that the Senate individual rate structure would boost the long-run level of GDP by 1.0 percent.

The House’s individual rate changes would generate slightly less growth than the Senate’s. The House plan would consolidate the current seven tax brackets into four, with rates of 12 percent, 25 percent, 35 percent, and 39.6 percent, while widening the distance between the brackets. However, the plan also contained a “bubble” in the top bracket to recapture some of the benefits of the lower rates for wealthy taxpayers. Because of its marginal rate effects, this provision dampened some of the growth potential of the House plan. Thus, we estimate that the House individual rate structure would boost the size of the economy by 0.9 percent in the long run.

#4 House Estate Tax Repeal

The House proposed to first double the basic estate tax exemption from $5 million to $10 million through 2024, then eliminate the estate and generation-skipping tax in 2025 and beyond. Dollar-for-dollar, the estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. is one of the most economically harmful taxes because it levies an exceptionally high 40 percent marginal tax rate on a very narrow base of capital income. Thus, the tax’s damage to the economy exceeds the small amount of revenue—$19 billion annually—that it raises for the federal treasury. We estimate that the House estate tax repeal provision would increase the size of GDP by 0.7 percent in the long run.

#5 Senate Pass-Through Proposal

The original Senate “Chairman’s Mark” proposed a 17.4 percent deduction of qualified business income from certain pass-through businesses. Specific service industries, such as health, law, and professional services, were excluded. Joint filers with income below $150,000 and other filers with income below $75,000 can claim the deduction fully on income from service industries. (The Senate-passed version of the bill increased the deduction to 23 percent. We have not scored that provision.) We estimate that the original Senate pass-through provision would increase the size of GDP by 0.6 percent in the long run.

#6 House and Senate Standard Deduction Proposals

The House and Senate plans were nearly the same when it came to increasing the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. . The House plan would increase the standard deduction from $6,350 to $12,200 for singles, from $12,700 to $24,400 for married couples filing jointly, and from $9,350 to $18,300 for heads of household. The Senate plan was slightly less generous, increasing the deduction to $12,000 for single filers, $18,000 for heads of household, and $24,000 for joint filers. Both plans indexed the standard deduction to chained CPI. We estimate that the House and Senate standard deduction provisions would increase the size of the economy by 0.4 percent in the long run.

#7 House Pass-Through Provisions

In contrast to the Senate’s pass-through proposal, the original House bill proposed a special top rate of 25 percent for pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income, subject to various anti-abuse rules. Like the Senate plan, it excluded various service industries, but unlike the Senate plan it dictated that 30 percent of business income be declared capital income and 70 percent be wage income. We estimate that the House’s pass-through provision would increase the size of the economy by 0.3 percent in the long run.

#8 Senate and #9 House Child Tax Credit Proposals

Both the House and Senate plans proposed a substantial increase in the child tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. , but there were considerable differences between the proposals.

- The Senate plan increased the child tax credit amount to $1,650. Initially, only the first $1,100 of the credit is refundable. It would increase the phaseout threshold of the credit to $500,000 for married filers and $250,000 for other filers. Also, it would allow the credit to be claimed for children under age 18 and would create a $500 nonrefundable credit for non-child dependents. We estimate that the Senate child tax credit provisions would increase the size of GDP by 0.2 percent in the long run.

- The House plan increased the child tax credit to $1,600, with $1,000 of the tax credit initially refundable. The refundable portion is indexed to inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. until the full $1,600 is refundable. The phaseout threshold for the child tax credit is also increased: for married households, it rises from $110,000 to $230,000. We estimate that the House child tax credit provisions would increase the size of GDP by 0.1 percent in the long run.

#10 Senate Doubling of the Estate Tax ExemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax.

In contrast to the House’s proposal to eventually repeal the estate and gift tax, the Senate chose to double the estate and gift taxA gift tax is a tax on the transfer of property by a living individual, without payment or a valuable exchange in return. The donor, not the recipient of the gift, is typically liable for the tax. exemption amount from $5 million to $10 million. (This provision was amended on the floor to sunset at the end of 2015.) We estimate that the Senate’s original estate tax proposal would increase the size of GDP by 0.1 percent in the long run.

Conclusion

Conferees face the challenge merging two pro-growth tax plans into a single plan that can pass both chambers. They also must make numerous trade-offs to keep the net revenue loss of the plan below $1.5 trillion, as is required by the joint budget resolution. Thus, they will have to prioritize provisions according to some standard. That standard should be economic growth.

As these examples have shown, there is a wide gulf between the major provisions in the House and Senate plans in terms of their growth potential. Thus, every compromise must avoid trading the most growth-producing provisions for those that may be politically popular but which do little or nothing to improve the economy. Ultimately, all Americans will be worse off as a result.

[i] These scores were derived within the context of the complete House and Senate bills and should be considered as guidance since the scores could change depending upon the other items in the final conference bill.

Share this article