What You’ll Learn

- Discover why there are better and worse ways for governments to raise a dollar of revenue.

- Compare the economic impact of the three basic tax types—taxes on what you earn, buy, and own—including three specific taxes within each category.

- Learn about the basics of “dynamic scoring,” one tool economists can use to compare the economic and revenue impact of different taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. policies.

Introduction

There are better and worse ways to raise a dollar of revenue. That’s because no two taxes impact the economy the same.

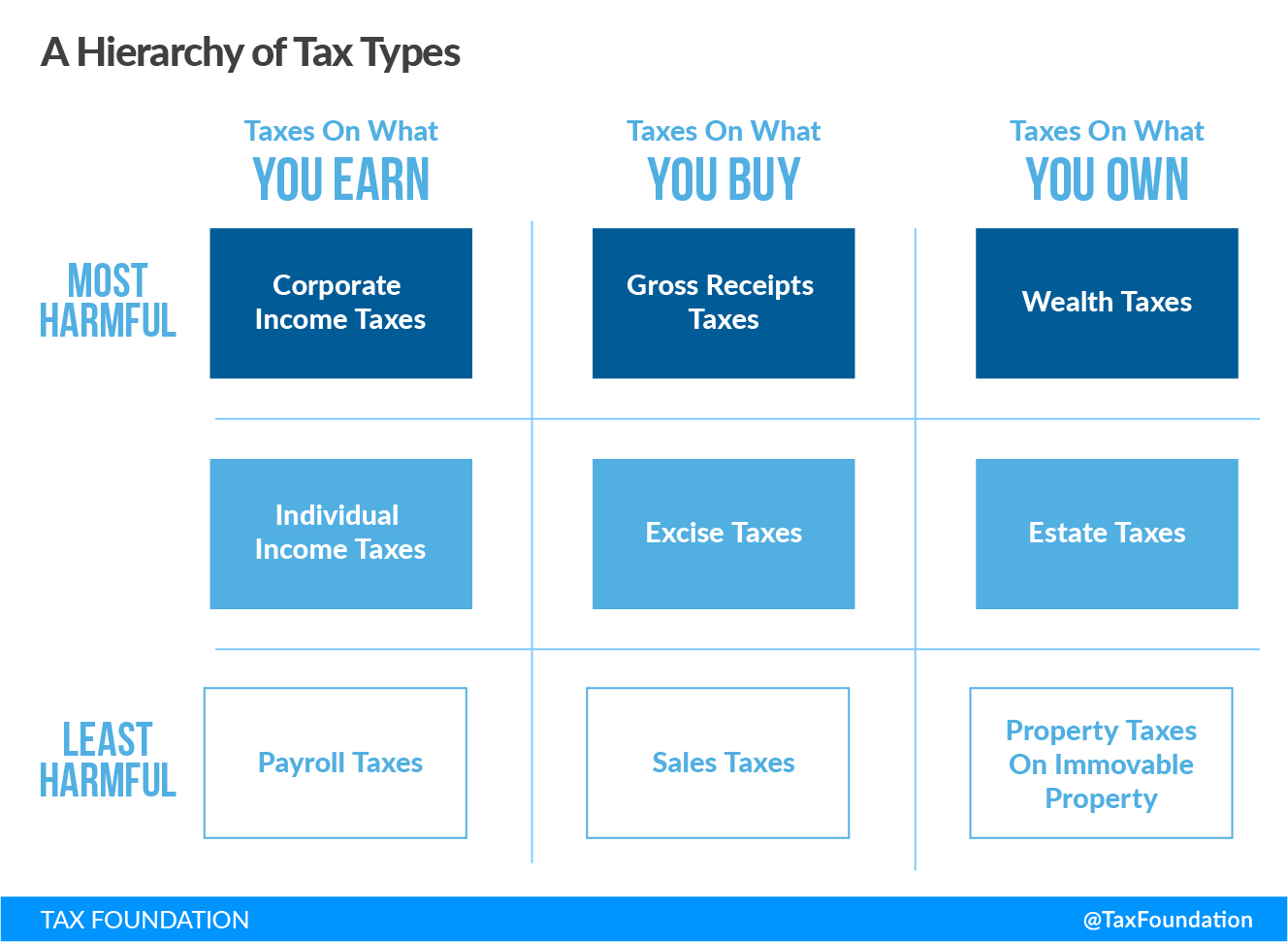

One way to think about this is as a hierarchy: which taxes are most and least harmful for long-term economic growth? This hierarchy is determined by which factors are most mobile, and thus most sensitive to high tax rates—in other words, which economic activities, if taxed, can easily be moved, reduced, or otherwise changed to avoid that tax?

Taxes on the most mobile factors in the economy, such as capital, cause the most distortions and have the most negative impact. Taxes on factors that can’t easily be moved, such as land, are the most stable and least distortive.

It’s relatively easy for someone to invest less to avoid a capital gains tax, for example. It’s much harder for someone to pull up stakes and move their home to avoid a property tax. This difference is why capital gains taxes distort people’s decisions, and thus the economy, more than property taxes.

Taxes on What You Earn

Corporate Income Taxes

Corporate income taxes are taxes on business profits earned by C corporations. The corporate income tax directly increases the cost of making investments in capital, like machinery and equipment, which businesses and workers use to be more productive. When businesses and workers are more productive, the economy grows. So, by increasing the cost of making investments, the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. discourages investment and productivity growth, creating one of the largest negative impacts on economic growth compared to other taxes. This distortion occurs when the base is defined with depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. rather than expensing. In fact, compared to other taxes, the corporate income tax is perhaps the most harmful type of tax for economic growth and worker wages.

Individual Income Taxes

Individual income taxes are applied to wages and salaries, business income from pass-through businesses like sole proprietorships and LLCs, and investment income. High marginal tax rates, the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income, reduce individual incentives to work and business incentives to invest. That means individual income taxes also have a negative effect on the economy.

Payroll Taxes

Payroll taxes are paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes apply only to labor income, not savings, and not to business income like the previous two forms of tax. For this reason, payroll taxes are one of the least harmful ways to raise revenue, as the supply of labor is less responsive to taxation than the supply of capital. That said, it’s important to note that employees bear the burden of payroll taxes, resulting in lower wages.

Taxes on What You Buy

Gross Receipts Taxes

Gross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales without allowing any deductions for costs. Unlike sales taxes or value-added taxes, gross receipts taxes are applied to business-to-business transactions and final consumer purchases. Since the tax is applied at each transaction in a production chain, without allowing for any deductions, it leads to tax pyramiding, where the many layers of tax are built into the final price of the good. By providing an advantage to businesses with short production chains, while harming those with long production chains, gross receipts taxes distort business decisions and the economy.

Excise Taxes

Excise taxes are imposed on a specific good or activity, such as cigarettes, alcohol, and fuel. Because of their narrow base (applying a tax to a small selection of goods or services) excise taxes distort production and consumption choices. Sometimes this distortion is intentional: to minimize externalities caused by the usage of the product or to reduce the consumption of the product overall, like a tax on cigarettes. However, this distortion makes excise taxes an inefficient source of revenue. Excise taxes with broader bases, or those levied in direct connection with the consumption of public goods, like gas taxes paying for road usage, better resemble pure consumption taxes and have less distortive effects.

Sales Taxes

Sales taxes are imposed on retail sales of goods and services. Ideally, sales taxes are imposed on all final retail sales of goods and services, but not on intermediate business-to-business transactions in the production chain, as in the case of gross receipts taxes. By applying to consumption, sales taxes don’t affect investment or saving, but can still reduce returns to work, discouraging labor supply. Sales taxes are less distortive than capital and income taxes and, when appropriately structured, do not lead to tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action. or changes in consumption.

Taxes on What You Own

Wealth Taxes

Wealth taxes are imposed annually on an individual’s net wealth. Net wealth is calculated by taking the market value of their total owned assets—the price those assets would get if sold—and subtracting their liabilities—everything that person owes, including loans, mortgages, and other debts. Wealth taxes place a high tax burden on the normal return to capital (the amount required for an investor to break even on an investment) and a lighter burden on the supernormal returns to capital (amounts above and beyond the normal return); this is the opposite of ideal tax policy. By placing a higher burden on the normal return to capital, wealth taxes distort investment decisions and can alter entrepreneurship, venture capital funding, and even where talent is located (in Silicon Valley vs. Hong Kong, for example).

Estate Taxes

Estate taxes are levied on the value of property that is transferred to heirs upon the death of the original owner and can be thought of as a one-time wealth tax. These taxes lead to unproductive tax planning, increase the tax burden on saving by encouraging people to consume their income rather than save it, and may have negative effects on entrepreneurship.

Property Taxes

Property taxes can be levied on immovable or “real” property (i.e., land and buildings) and personal property (i.e., cars, machinery, office equipment, etc.). When properly structured, property taxes can be relatively economically efficient and transparent, such as when they apply to immovable property, like annual taxes on land and buildings. Taxes on immovable property have a relatively small effect on decisions to work and invest, though they can impact where a person or business chooses to locate. Because personal property is much more mobile, and thus more sensitive to taxation, personal property taxes distort investment decisions, complicate business tax compliance, and reduce economic growth.

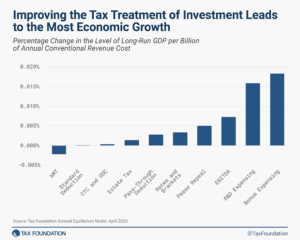

Bang for Your Buck: Ranking 10 Hypothetical Tax Changes

Instead of focusing on the relative harm of different tax types, think about it in the reverse: which taxes can be reduced to improve the economy? One way to answer this question is to use dynamic scoringDynamic scoring estimates the effect of tax changes on key economic factors, such as jobs, wages, investment, federal revenue, and GDP. It is a tool policymakers can use to differentiate between tax changes that look similar using conventional scoring but have vastly different effects on economic growth. to produce what we refer to as a “bang for your buck” analysis—a ranking of how much economic growth is produced per dollar of revenue forgone by different tax reductions.

The chart below considers 10 tax cuts related to key provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and the resulting effect on the size of long-run economic growth.

These include:

- Improving the tax treatment of investments through a continuation of bonus expensing

- Changes to research and development (R&D) expensing

- Changes to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA)

- Repeal of the Pease limitation on itemized deductions

- Adjustments to tax rates and brackets

- Changes to the pass-through deduction

- Adjustments to the estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs.

- An increase in the child tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. (CTC) and credit for other dependents (ODC)

- A larger standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot also itemize their deductions; it serves as an alternative.

- Changes to the alternative minimum tax (AMT)

As you can see below, AMT changes are the least efficient option to produce economic growth. Dollar for dollar, bonus expensing—which allows companies to fully and immediately deduct the cost of all new investments—is by far the most efficient way for policymakers to generate economic growth through changes to the tax code. This is followed closely by R&D expensing, which encourages business investment and boosts productivity.

The relative increase in economic output that tax reductions generate per dollar of lost revenue clearly illustrates that not all taxes (and not all tax cuts) are equal.