Conversations about “loopholes” in the tax code are often unproductive. “Loophole” is a loaded word, one that sneaks in hidden assumptions without justifying them. But loaded words are often effective; especially, apparently, the word “loophole.” As a result, the word has been used far too often and applied in all sorts of inappropriate situations. The end result has been a debate crippled by equivocation. Here’s what I mean by that.

To describe something as a “loophole” has a built-in negative emotional response to it. The word is traditionally used to describe an unintended provision (or lack of a provision) in a law or a contract that allows someone to avoid their obligations. In taxes, for example, that could be a gap in the income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. that allows people to earn untaxed income.

In describing something as a loophole, though, you have already assumed what you wanted to prove. If people are getting out of their income taxes via some unintended technicality in the law, by all means, that should be patched up.

For a real-life example of a loophole, consider “mandatory donations” to popular college sports teams in order to get season tickets. This was a clever way of selling tickets (by all means, a “mandatory donation” in exchange for something is a sale) while giving them the appearance of a deductible charitable donation for the purposes of the IRS. This was clearly not an intended effect of the deduction for charitable contributions; therefore, it meets the true definition of a loophole. This loophole was partially rolled back through further legislation, and the President’s most recent budget would eliminate it entirely.

However, the word “loophole” is clearly misused when applied to deliberate, well-known policy provisions. For example, the mortgage interest deduction is no more a loophole in the tax code than Memorial Day sales are a loophole in mattress pricing. The deduction is sitting right there on Schedule A. It’s not some hidden obscurity. (As a side note, if you can explain the thematic connection between Memorial Day and mattress purchases, you are a much smarter human than I am.)

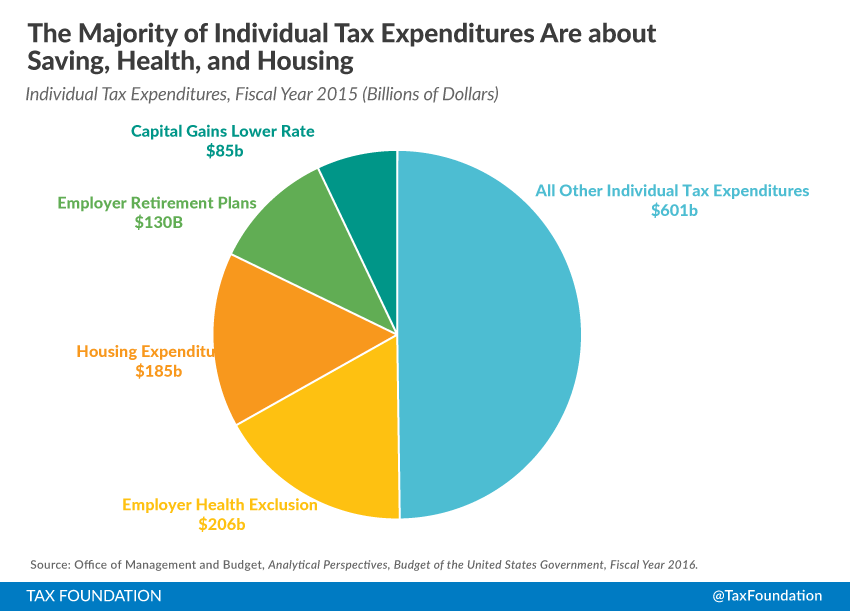

There is a better phrase to describe such deliberate tax provisions, ones designed with the explicit intention of changing the income tax code. We call these “tax expenditures,” and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) frequently tallies these up so that people can see what they are. Earlier this week, I published an overview of the largest corporate and individual tax expenditures in our code, as measured by the JCT. These large expenditures are all well-known to the tax community, and generally very clearly outlined in legislation.

Conversation, then, is most unproductive when it equivocates between loopholes and the large tax expenditures. There are strong rhetorical advantages to talking about closing loopholes. However, many tax expenditures themselves sound pretty compelling if you talk about them specifically. For example, many of them prioritize health, housing, and saving:

The most rhetorically powerful strategy, then, is to promise lots of money for tax reform by “closing loopholes,” using tax expenditures as evidence for this claim. Then, when pressed on specific loopholes, avoid naming any. This strategy, in addition to being rhetorically powerful, is of course entirely devoid of meaning. Closing loopholes and lowering rates sounds like a win-win. It sounds a little bit like one of those typical political promises that are too good to be true. That’s because it is.

What’s needed, with respect to tax expenditures, is a sober look at each one, with consideration for the purposes behind them.

My full report on tax expenditures can be found here.

Share this article