As increased political attention focuses on the state of the American worker, expect to see a resurgence of the argument that the labor share of income is in decline. The problem with the argument is that it ignores that some categories counted as income in national accounting statistics don’t actually end up in the pockets of workers or capital owners. Removing the categories of income that are not actually income reveals that labor and capital shares are well within their historical range.

If the goal of measuring income shares is to reach conclusions about people’s welfare, then the appropriate measure is one that captures the amount of output available for current consumption or to invest in expanding future production. Though a statistic called “gross domestic income” or GDI is often cited for this purpose, it is unfortunately not a good fit. That is because some of what is counted in GDI does not actually end up in people’s pocketbooks.

For instance, depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. is income set aside to replace worn down assets. Replacing worn down assets simply returns the economy back to its previous level of production, but GDI counts it as a type of capital income. Instead, it should be netted out if we are trying to measure the income people can actually consume. Likewise, though smaller in scale, some types of taxes are incurred during the production process, but it is not clear whether labor or capital pays for them. Rather than counting them as capital income, they should be netted out, too.

Excluding both categories lets us look specifically at the capital and labor income earned on net by people in the United States.

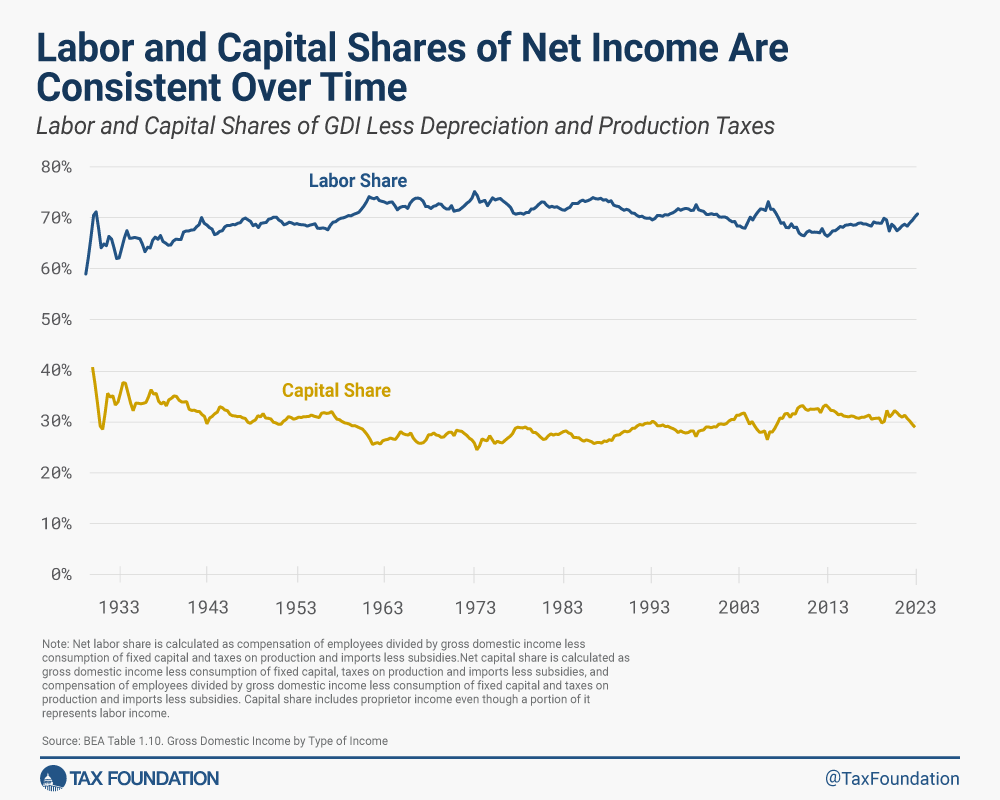

The chart below shows labor and capital shares of net income from 1929 through Q2 2023, indicating that labor and capital shares are now remarkably close to their long-run averages. The average labor share from 1929 through Q2 2023 was 69.9 percent and the average capital share was 30.1 percent. In 2022, the most recent complete year of data, the labor share was 69.0 percent and the capital share was 31.0 percent—well within historical range and far from a supposed decades long decline in labor share.

Net labor share includes wages and salaries as well as supplements to wages and salaries like health insurance and contributions for government social insurance. Together, they comprise labor income. Supplements to wages and salaries, or non-wage benefits, comprise a growing share of labor compensation, largely due to policy choices such as exempting employer-provided health insurance from income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. and contributions to entitlement programs.

Net capital share includes proprietor’s income (the income of noncorporate businesses such as sole proprietorships and partnerships); corporate profits (including S corporations); interest income and miscellaneous business payments; and housing income—together they comprise capital income. (It also includes a very small amount for government enterprises.) Proprietor’s income represents both capital and labor income as owners are compensated both for work and investment in their businesses. Because the split is hard to determine, it is all counted as capital income.

It does not include depreciation or taxes on production less subsidies. The issue of counting the two categories as income when trying to study welfare or inequality was explained by BEA economist Benjamin Bridgman in a 2017 paper (updated from 2014). He finds that while the U.S. labor share of gross income has been dropping since the 1970s, using “the correct measure” of net income that nets out what doesn’t add to capital (production taxes and depreciation) indicates “the overall picture is no longer one of unprecedented, globally declining labor share.”

In other words, the historic low labor share often cited is largely attributable to increasing depreciation as well as production taxes.

Similarly, in a 2015 paper, economist Matthew Rognlie argues that looking at the net measure is more applicable when discussing distribution and inequality “because it reflects the resources that individuals are ultimately able to consume.”

Rognlie also takes a closer look at changes within the capital share of income. He finds “the net capital share generally fell from the beginning of the sample through the mid-1970s, at which point the trends reversed. In the long run, there is a moderate increase in the aggregate net capital share, but this owes entirely to the housing sector.”

While the net capital share in the housing sector has moderately increased since the 1970s, the long-term movement of the net capital share overall has generally remained steady, including in the corporate sector of the economy. Housing includes all homes, whether rented or owned, and includes the surplus value housing provides to homeowners even after accounting for money lost to upkeep and interest. The rise in housing share means that the capital share is not being supported by increased employer bargaining. Instead, it is by holders of urban land and housing permits—mostly individual homeowners, with landlords as a substantial minority.

In conclusion, multiple studies find the shares of net income going to labor and capital have not changed substantially over more than 90 years. Both shares are well within their historical range, and recent changes are primarily driven by factors like exclusions for employer-provided health insurance and the returns to owner-occupied housing.

Policymakers should remember that capital and labor are the main inputs to production, and they are complementary—more capital increases labor productivity, and more labor increases the return to capital. Ultimately, concerns over inequality should focus on differences within labor compensation rather than the split between labor and capital.

Share this article