Lawmakers have recently announced plans that would increase the taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. burden on wealthy Americans, ranging from higher marginal income tax rates to wealth taxes. These proposals are flawed in several ways, including in their lack of understanding of tax history.

While marginal income tax rates have come down from their highs of 91 and 92 percent in the 1950s, changes in the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. —how much and what types of income are subject to the tax—mean the effective rates on the wealthy haven’t changed nearly as much.

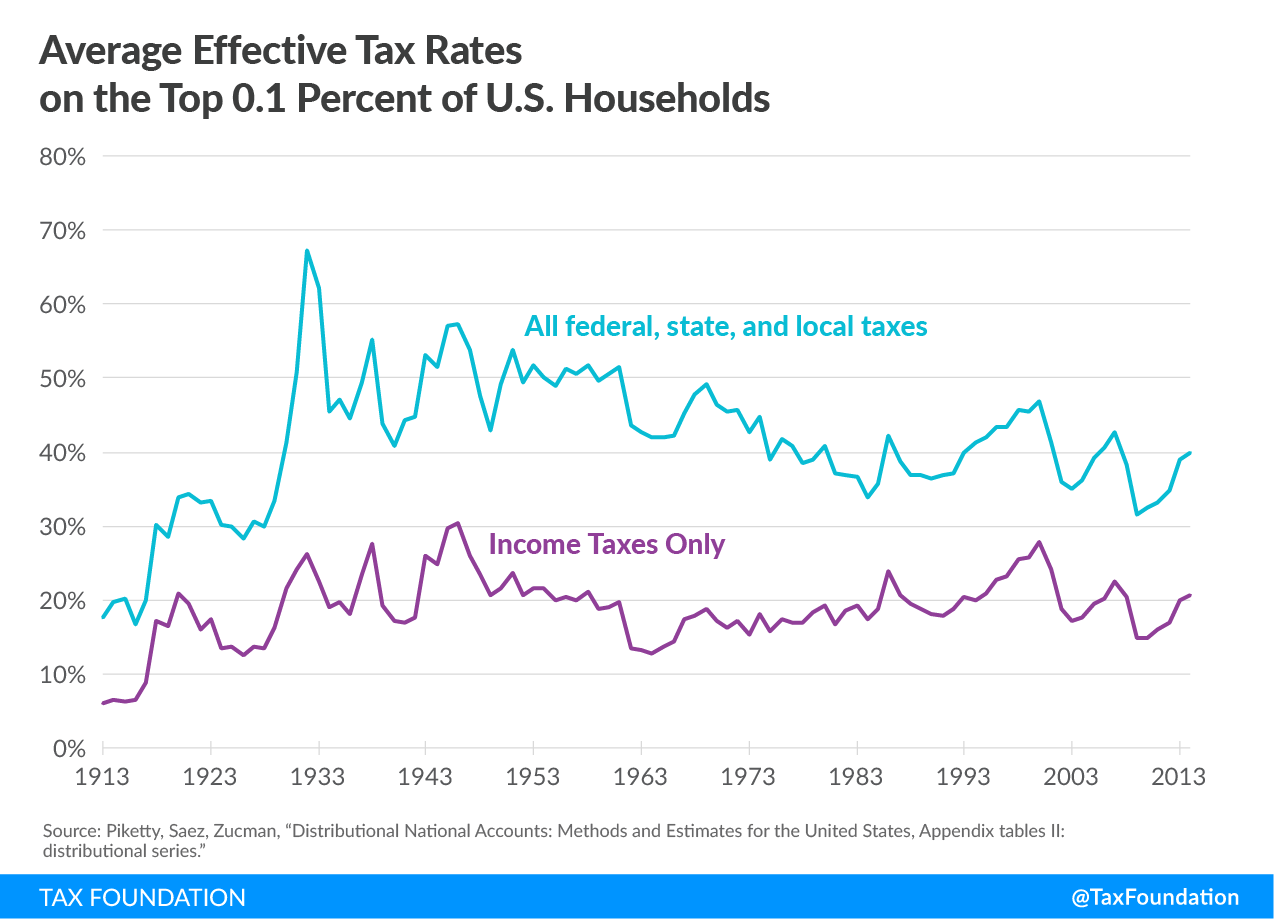

The graph below illustrates the average tax rates that the top 0.1 percent of Americans faced over the last century, based on research from Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman.[1] The blue line includes the impact of all federal, state, and local taxes on individual income, payroll taxes, estates, corporate profits, properties, and sales. The purple line shows income taxes only, including federal, state, and local.

While the average rates for total taxes on the top 0.1 percent have fallen 10.8 percentage points from the 1950s, average income tax rates have remained relatively stable. In the 1950s, the top 0.1 percent of households faced average effective income tax rates of 21.0 percent, versus 20.7 percent as of 2014.

How could it be that a top marginal income tax rate of 91 percent resulted in an average income tax rate (including state and local income taxes!) of only 21.0 percent for the top 0.1 percent during the 1950s? A previous Tax Foundation analysis explains:

- The 91 percent bracket of 1950 only applied to households with income over $200,000 (or about $2 million in today’s dollars). Only a small number of taxpayers would have had enough income to fall into the top bracket—fewer than 10,000 households, according to an article in The Wall Street Journal.

- Even among households that did fall into the 91 percent bracket, the majority of their income was not necessarily subject to that top bracket. After all, the 91 percent bracket only applied to income above $200,000, not to every single dollar earned by households.

- Finally, it is very likely that the existence of a 91 percent bracket led to significant tax avoidance and lower reported income. Many studies show that, as marginal tax rates rise, income reported by taxpayers goes down. As a result, the existence of the 91 percent bracket did not necessarily lead to significantly higher revenue collections from the wealthy.

Another factor to consider is that the wealthy aren’t a monolithic group of taxpayers. In fact, IRS data shows that there is typically a lot of churn within the group of top earners. For example, the number of taxpayers who report incomes of $1 million or more is highly variable, and fluctuates with the business cycle.

Ultimately, tax rates, while important, are only one part of the story. The top 0.1 percent of taxpayers pay nearly the same average tax rates today as they did in the 1950s because of other changes made to the tax system. And even with these changes, the American tax system is already highly progressive: according to the most recent IRS data, the top 0.1 percent of taxpayers paid more than six times the share of federal income taxes than the bottom 50 percent of taxpayers combined.

Context like this is crucial for discussions of how much the wealthy pay in taxes today, and how much they’ve paid over time. By historical standards, the very top income earners do not face an unusually low income tax burden.

Note: This is part of our “Putting a Face on America’s Tax Returns” blog series

- America Already Has a Progressive Tax System

- The Composition of Federal Revenue Has Changed Over Time

- The Top 1 Percent’s Tax Rates Over Time

- Who Benefits from Itemized Deductions?

- How Do Transfers and Progressive Taxes Affect the Distribution of Income?

- A Growing Percentage of Americans Have Zero Income Tax Liability

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe[1] Some of the distributional assumptions in the Piketty, Saez, and Zucman paper are questionable. In particular, the authors assume that the full burden of the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. falls on owners of capital, which may not be correct. It is likely that the corporate income tax burden falls on shareholders, workers, and consumers. See Stephen J. Entin, “Labor Bears Much of the Cost of the Corporate Tax,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 24, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/labor-bears-corporate-tax/.

Share this article