In The Triumph of Injustice, a new book released by economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, the authors argue for an overhaul of the American taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code that would make it more progressive, making the case for higher tax rates on high-earning taxpayers and a wealth taxA wealth tax is imposed on an individual’s net wealth, or the market value of their total owned assets minus liabilities. A wealth tax can be narrowly or widely defined, and depending on the definition of wealth, the base for a wealth tax can vary. on taxpayers with wealth above $50 million.

While Saez and Zucman’s data and methods are novel contributions, the authors fail to show why economists should reject the widely-accepted methods for determining tax burdens across the income distribution and do not present compelling evidence that high effective tax rates would minimally affect saving and investment decisions.

A Novel Approach to Measuring Tax Rates Across the Income Distribution

In their book and previous work, Saez and Zucman measure effective tax rates for taxpayers across the income distribution, taking into account taxes paid at the federal, state, and local levels as a share of national income. This builds on work done by Thomas Piketty, Saez and Zucman on distributional national accounts, which enables scholars to also examine growth rates across the income distribution by examining taxes paid as a proportion of national income.

The authors in this new book use survey data and tax records to compute effective tax rates for every income group in America by dividing all taxes paid by the sum of taxpayers’ adjusted gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total of all income received from any source before taxes or deductions. It includes wages, salaries, tips, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental income, alimony, pensions, and other forms of income. For businesses, gross income (or gross profit) is the sum of total receipts or sales minus the cost of goods sold (COGS)—the direct costs of producing goods, including inventory and certain labor costs. (AGI) reported on tax returns.

The authors also impute items that are not available on tax returns or surveys. For example, tax returns show if taxpayers received dividends but not if they own shares in corporations that have retained earnings. To factor retained earnings into taxpayer incomes, the authors must impute the value of those earnings for each taxpayer by using existing data, such as dividends they received.

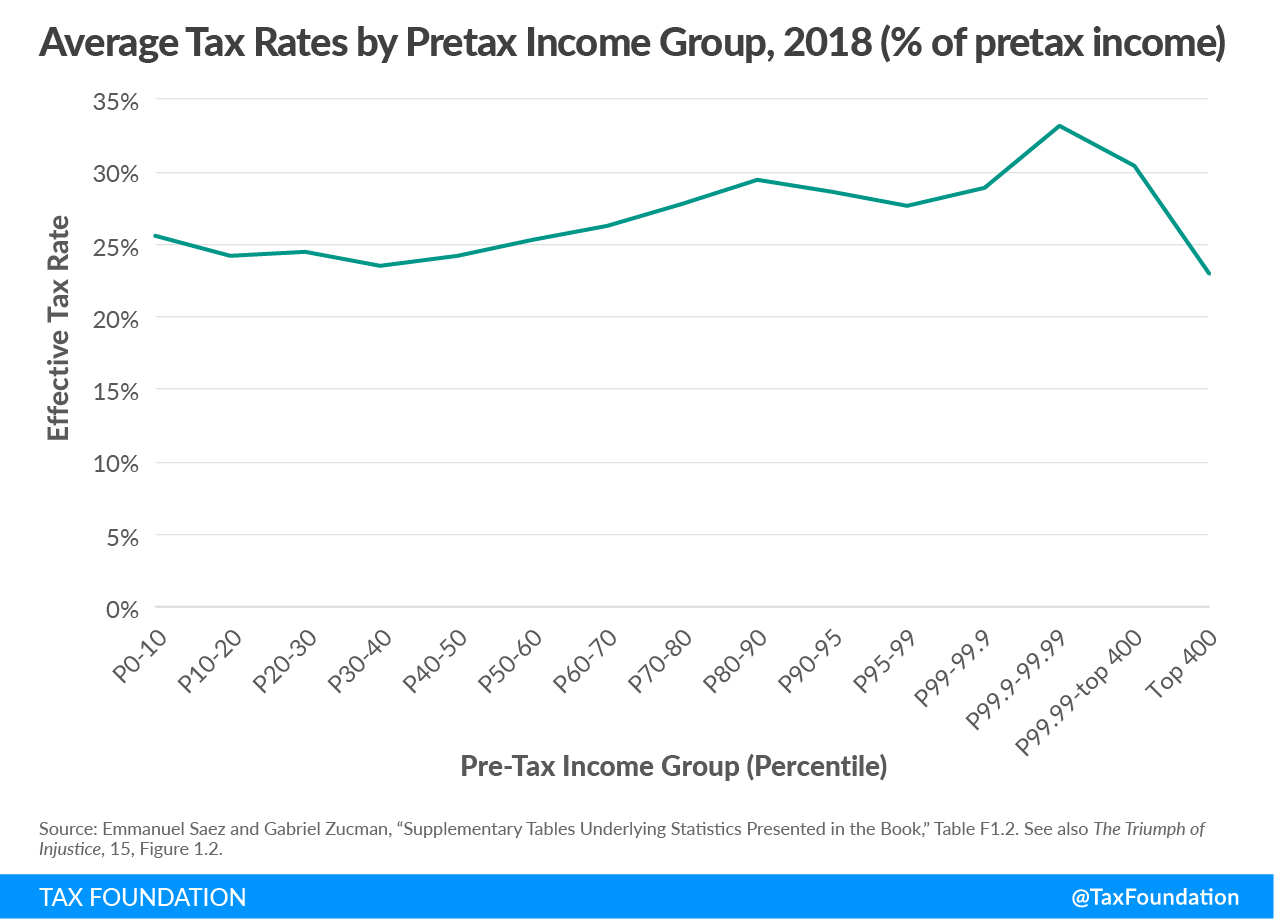

Saez and Zucman find that when accounting for federal, state, and local taxes, the U.S. tax system is a flat taxAn income tax is referred to as a “flat tax” when all taxable income is subject to the same tax rate, regardless of income level or assets. —most income groups pay a similar amount of tax as a percentage of pretax income—with the exception of the very top of the income distribution, which has a lower effective tax rate.

The authors argue that taxpayers at the top of the income distribution pay less in tax as a percentage of their income due to a low corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate, preferential tax rates for long-term capital gains, and tax avoidance.

Other taxes, such as state-level sales taxes and the federal payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. , make up a higher proportion of low-earner incomes when compared to high earners and contribute to Saez and Zucman’s finding that the U.S. tax system is regressive.

Relying on Questionable Methodological Decisions

While Saez and Zucman’s method provides a measure of effective tax rates on national income, their measure fails to account for the refundable portion of tax credits. They exclude the refundable portion of credits because they consider them to be a transfer to low-income taxpayers and including them would exceed 100 percent of national income. However, this method overstates the tax burden for taxpayers at the bottom of the income distribution, as the tax credits reduce tax owed and result in a refund when their tax returns are filled.

For example, in 2017, effective federal income tax rates were negative for taxpayers making less than $20,000 and about 3 percent in 2017 for taxpayers making between $20,000 and $50,000. While more regressive state and local taxes raise this effective tax rate, the American tax system is still progressive when accounting for refundable tax credits and other quasi-cash transfers.

In the new book, Saez and Zucman challenge how economists should assess the economic incidence of taxation, arguing that “it is crucial to distinguish current distributional analysis from tax reform distributional analysis.” Economic incidence is important to consider when evaluating effective tax rates, as who bears the economic burden of a tax may be different from who is statutorily required to remit the tax.

To consider economic incidence, economists may allocate taxes to taxpayers other than the ones who must statutorily remit it. For example, while employers must remit half of the payroll tax, the economic incidence is fully borne on employees and may be allocated to them when examining effective tax rates. This makes a difference in the distribution of the tax burden, as taxes paid by employers may fall on taxpayers who are higher earning than taxes paid by employees.

The authors allocate labor taxes (e.g., payroll taxes, income taxes) on labor and capital taxes (e.g., corporate income tax, capital gains taxes) on capital, differing from the standard treatment of incidence. This makes the tax distribution relatively more progressive when taxes on capital are higher and increases the level of regressivity they measure in the federal tax code when effective taxes on capital are reduced.

For example, the authors also allocate none of the corporate income tax onto labor, diverging from the allocation (25 percent onto labor) used by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Tax Policy Center (25 percent onto labor), and other economists. This has a similar effect on the distribution of the tax burden over time, as it raises effective tax rates on taxpayers with high incomes and shows an increased level of regressivity when taxes on capital are reduced and high-income taxpayers disproportionately benefit.

The authors were required to impute and allocate income to taxpayers that does not show up on individual tax returns, which makes effective tax rates sensitive to imputation assumptions. For example, Saez and Zucman change the method used in distributional national accounts data published by the authors and Piketty in the Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Now, instead of allocating corporate income taxes to all owners of capital, Saez and Zucman allocate the taxes only to owners of shares (and not other forms of capital like bonds), leading to more regressivity at the very top of the income distribution when capital tax rates are reduced. This choice diverges from standard practice, as it is expected that a corporate income tax will lead to taxpayers shifting into noncorporate capital assets.

In addition to these questionable methodological decisions, the authors make nonstandard assumptions about the distribution of the sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. and how to allocate unreported income. Saez and Zucman allocated unreported income as a proportion of reported income, which heavily skews toward the top of the income distribution, despite Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audits finding that unreported income exists disproportionately at the lower levels of the distribution.

Economic Effects Must be Considered When Considering Higher Tax Rates

When considering the behavioral effects of higher tax rates on the wealthy, the authors argue that economic decision-making (e.g., the decision to invest) is minimally affected. This runs counter to how they see a wealth tax impacting the American capital stock. Saez and Zucman argue that a wealth tax would not reduce the capital stock in the United States, because any reduction would be offset by increased investment by foreigners. This assumes that foreigners are changing their economic behavior in response to the tax, not merely changing their avoidance tactics, suggesting that tax policy can induce shifts in economic behavior.

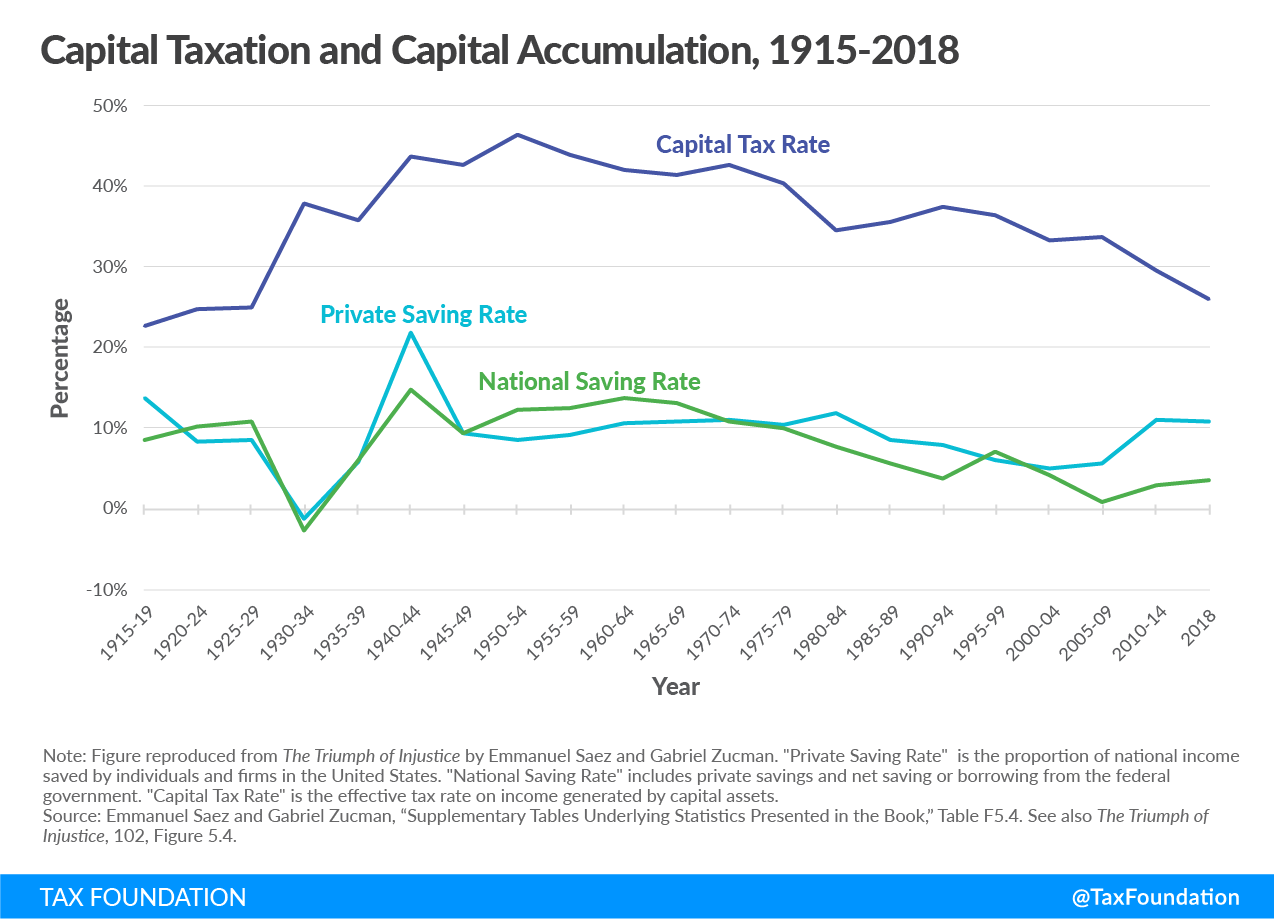

To provide evidence for their claim about economic behavioral effects, Saez and Zucman examine private and national savings rates in the 20th century when compared to the average effective tax rate on capital income (Figure 2) and argue that a decline in the effective tax rate on capital is not associated with an increase in savings rates. This may imply that lower effective tax rates do not spur greater capital investment.

A simple comparison of savings rates with effective capital tax rates does not reveal the relationship between the two due to confounding variables and the lack of a counter-factual point of comparison. The economic literature is ambiguous on whether average effective tax rates on capital alter savings rates.

Additionally, Saez and Zucman fail to engage with voluminous literature on the economic impact of tax policy, which attempts to quantify how tax burdens shift economic decision-making. The authors correctly point out that many other factors drive investment and saving decisions other than effective tax rates but fail to extend this point to their own analysis when comparing savings rates and taxes on capital.

When evaluating the impact of taxes on investment and saving decisions, it is important to consider the marginal effective tax rate on capital in addition to the average effective tax rate. The marginal effective tax rate shows the tax wedgeBroadly speaking, a tax wedge is the difference between the pre-tax price or return and after-tax price or return. For labor income, it is the difference between the total labor costs to the employer and the corresponding net take-home pay of the employee. on investment, or the portion of a break-even investment (one that makes no profit) that must cover the tax burden. It is an indicator of how tax rates impact investment decisions.

Focusing solely on average tax rates obscures the incentive to invest on the margin. For example, marginal effective tax rates on capital in the mid-1980s were effectively negative despite higher average tax rates, according to some studies.

In addition to the authors’ proposals to raise taxes on top income earners and the wealthy, The Triumph of Injustice proposes reasonable reforms such as integration of the individual income and corporate income taxes, which would reduce economic distortions by making decisions such as business form and sources of funding (debt or equity) neutral in the tax code. Likewise, the authors are correct that there needs to be a renewed effort to streamline anti-avoidance efforts internationally, though one of their preferred solutions—international cooperation and sanctions on tax havens—would be difficult to enforce.

Saez and Zucman have provided a valuable contribution to the tax policy debate over how to tax the wealthy and improve capital taxation in the U.S. However, the debate over how the wealthy and upper-income earners should be taxed must directly grapple with tried-and-tested methods of evaluating the tax burden on taxpayers and consider the economic impacts of their proposed reforms.

Share this article