Today’s taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. map examines the extent to which states adopt a harmful set of tax policies known as throwback and throwout rules. Although these rules may be unfamiliar and seem arcane, they can substantially increase corporations’ tax liability and influence business decision-making. Throwback rules have multiple negative effects on state business activity, including reduced new corporate investment and lower rates of economic efficiency. Throwback rules and throwout rules erode the competitiveness of states that impose them by incentivizing firms to relocate to non-throwback and throwout states to avoid higher corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. burdens.

Throwback rules were originally designed to capture foregone corporate income tax revenue generated as a result of the Interstate Income Act of 1959. More commonly known as Public Law 86-272, the statute establishes limits on states’ ability to assert nexus over certain business activity. To make sense of this, it is necessary to discuss how corporate income is apportioned to states for tax purposes.

The standard apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’s profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income tax or other business tax. US states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders. method began by requiring corporations to apportion their profits by three unique factors relevant to nearly all business models: payroll, property, and sales. Thirty-four states utilize single sales factor apportionment, which requires companies to only take sales into consideration when apportioning their profits to each state in which they have an established economic nexus. The remaining states either use a traditional, evenly weighted three-factor apportionment method or use all three factors but with additional weight on sales. In all cases, a state can only apportion income if it has economic nexus, which is defined as an adequate connection that corporations must meet for states to impose a corporate income tax collection obligation.

P.L. 86-272 prohibits states from taxing income that arises from the sale of tangible property into the state by a company that has no other activity in that state other than soliciting sales. When companies sell into a state where they do not have nexus, that destination state lacks jurisdiction to tax the company’s income. This results in what is known as “nowhere income”—income that cannot legally be taxed by the state where the income-producing sale occurs.

Under throwback rules, sales of tangible property that are not taxable in the destination state are “thrown back” into the state where the sale originated, even though that is not where the income was earned. This means that if a company located in State A sells into State B, where the company lacks economic nexus, State A can require the company to “throw back” this income into its sales factor.

The single sales factor mentioned above is a part of the numerator of the fraction used when firms calculate their apportionment for each state in which they meet economic nexus requirements. Throwback rules increase corporations’ tax liability by increasing the numerator of this fraction, thus causing a firm to be on the hook for more sales than if the nowhere income were not thrown back into the numerator of the apportionment formula.

Even if it might be fairer for a company to pay taxes on this nowhere income (although it is also unfair that they face double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. on other income), throwback rules are a case of the wrong tax, at the wrong rate, in the wrong state. They cause businesses to be taxed at potentially many multiples of the income they have in the state imposing the throwback rule, motivating these businesses—or at least certain aspects of their business—to locate elsewhere. This effect is so robust that studies find throwback rules actually decrease tax revenue over time, since they do more to drive out business activity than they do to tax the nowhere income from remaining businesses with exposure to the provision.

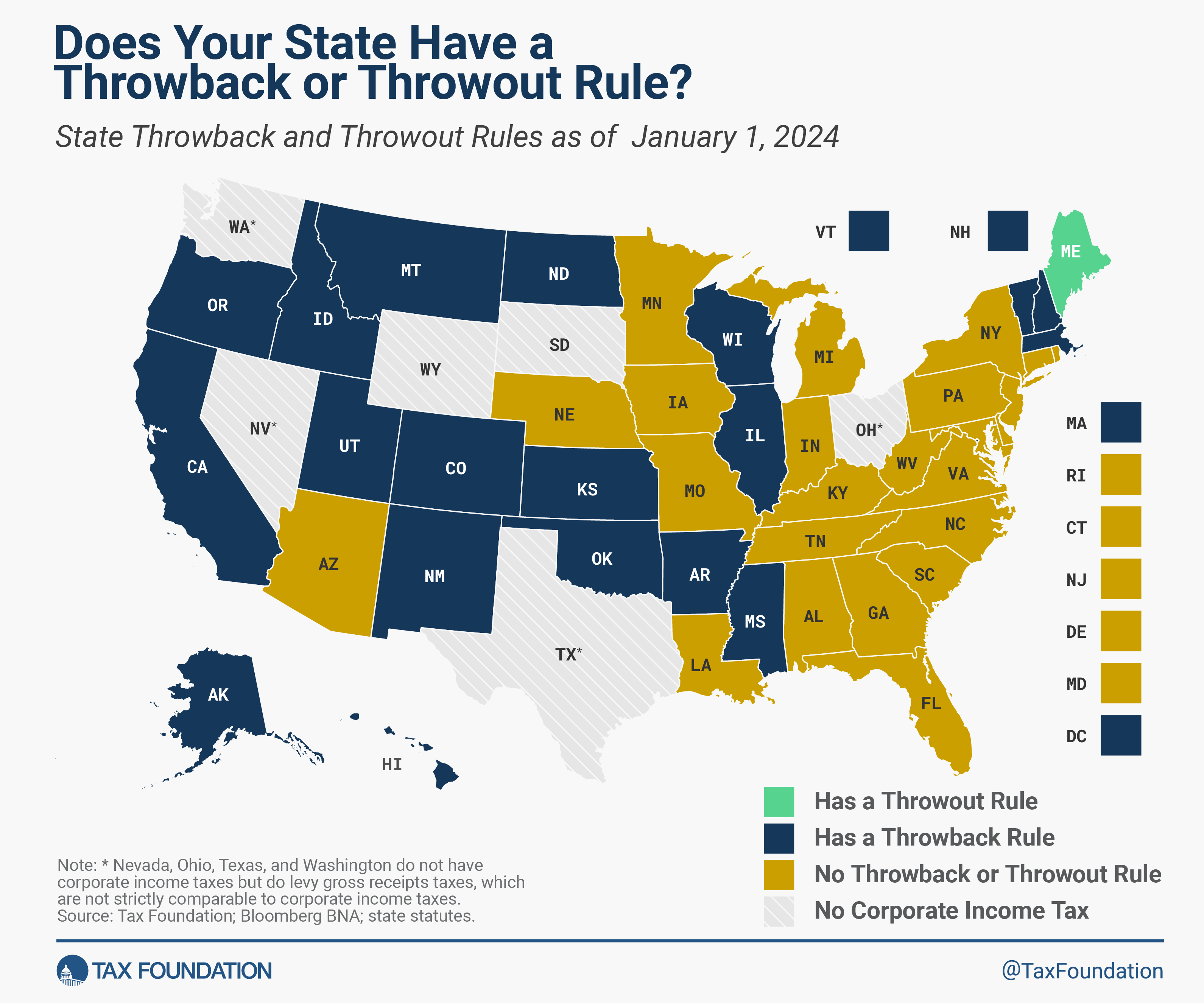

Throwback rules include out-of-state sales of tangible personal property in the numerator of the apportionment fraction. This increases the share of sales included in the numerator of the apportionment formula. As a result, states with throwback rules increase firms’ corporate income tax liability. Meanwhile, Maine has what is known as a throwout rule for sales of tangible personal property, where it requires corporations to exclude, or throw out, these nowhere income-creating out-of-state sales of tangible personal property from the denominator of the apportionment fraction. This has a similar effect of increasing the corporate tax liability of a particular firm located there. Finally, 27 states and the District of Columbia require firms to throw out sales of intangible personal property from the denominator of total executed sales in their apportionment formula.

State throwback and throwout rules increase businesses’ tax liability in states that impose them, often dramatically. They are also structurally unsound as they distort firms’ economic decision-making and investment decisions. Eliminating these provisions creates headway for sound tax policy, eliminating a significant disincentive for in-state investment. States have generally tried to encourage capital investment. Throwback and throwout rules are an unfortunate example of penalizing it.

Does Your State Have a Throwback or Throwout Rule?

State Throwback and Throwout Rules as of January 1, 2024

| States | Throwback or Throwout Rules |

|---|---|

| Alabama | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Alaska | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Arizona | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Arkansas | Has a Throwback Rule |

| California | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Colorado | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Connecticut | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Delaware | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| District of Columbia | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Florida | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Georgia | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Hawaii | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Idaho | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Illinois | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Indiana | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Iowa | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Kansas | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Kentucky | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Louisiana | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Maine | Has a Throwout Rule |

| Maryland | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Massachusetts | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Michigan | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Minnesota | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Mississippi | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Missouri | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Montana | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Nebraska | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Nevada | No Corporate Income Tax* |

| New Hampshire | Has a Throwback Rule |

| New Jersey | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| New Mexico | Has a Throwback Rule |

| New York | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| North Carolina | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| North Dakota | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Ohio | No Corporate Income Tax* |

| Oklahoma | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Oregon | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Pennsylvania | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Rhode Island | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| South Carolina | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| South Dakota | No Corporate Income Tax |

| Tennessee | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Texas | No Corporate Income Tax* |

| Utah | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Vermont | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Virginia | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Washington | No Corporate Income Tax* |

| West Virginia | No Throwback or Throwout Rule |

| Wisconsin | Has a Throwback Rule |

| Wyoming | No Corporate Income Tax |

Source: Tax Foundation; Bloomberg BNA; state statutes. Share this article