Over the past decade, the state taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. landscape has grown increasingly competitive as policymakers have sought to attract investment and promote economic opportunity and growth in their states. The past two years in particular have seen an extraordinary increase in tax reform efforts, given states’ strong revenue growth despite the pandemic and policymakers’ desire to make their states more attractive to an increasingly mobile workforce.

Most of the focus of these reform efforts has been on reducing state income tax rates, as corporate and individual income taxes are widely regarded by economists as more economically harmful than taxes on consumption and real property. Furthermore, states with low or no income taxes have seen significantly stronger gross state product growth and net inbound migration over the past decade than their higher income tax peers, and high-tax states are increasingly taking notice.

That’s why, in Wisconsin, comprehensive tax reform that prioritizes gross state product growth and personal income growth ought to be a top priority for policymakers, especially given the recent reforms made by many of Wisconsin’s regional and national peers.

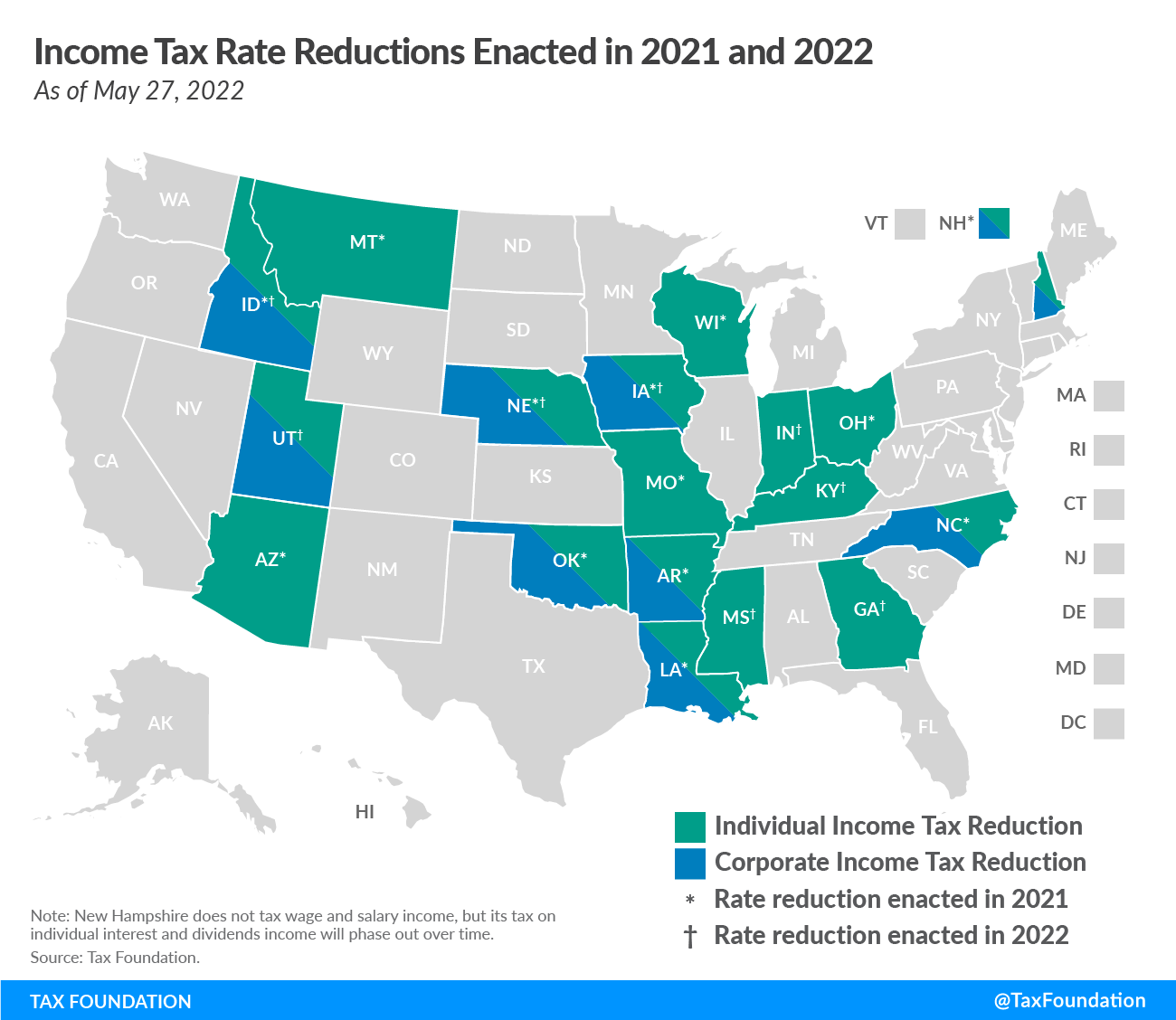

In 2021, Wisconsin was one of 13 states to enact laws permanently reducing individual and/or corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rates (several additional states implemented previously enacted cuts in 2021 as well). Thus far in 2022, eight states have newly enacted laws reducing income tax rates, and others may yet follow.

Many states are not only lowering their top marginal individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rates but are also consolidating brackets to create a more neutral, pro-growth environment that avoids penalizing additional labor and investment on the margin. In the first 109 years of state income taxation, only four states converted their graduated-rate individual income taxes into single-rate structures, but in the past year alone, four additional states—Arizona, Iowa, Mississippi, and Georgia—have enacted laws to move to a single-rate structure.

Increasingly, when it comes to income tax competitiveness, states that stand still risk falling behind and losing residents and business investment to their more tax-friendly peers.

Over the past decade, Wisconsin policymakers have enacted multiple iterations of tax relief, including income and property tax relief under Gov. Scott Walker (R), as well as a series of reductions to the three lowest marginal individual income tax rates that were passed by the Republican-controlled legislature and agreed to by Gov. Tony Evers (D). While the rate reductions in 2019, 2020, and 2021 are providing meaningful relief to those at the lower end of the income spectrum, recent tax changes have mostly danced around the edges of the tax code and have stopped short of comprehensive tax modernization that will truly promote long-term economic growth.

The only marginal individual income tax rate Wisconsin has left unchanged since 2019 is the one that has the most detrimental impact on labor and investment in the state: the top marginal rate. At 7.65 percent, Wisconsin’s rate is the 10th highest in the nation, lower than that of only eight states and the District of Columbia. While Wisconsin is among the 25 states that have lower top individual income tax rates now than in 2012, its competitive standing on income tax rates has fallen nonetheless, from 11th highest in the nation at 7.75 percent in 2012 to 10th highest in the nation in 2022 at 7.65 percent.

Reductions to the top marginal rate are more likely to promote economic growth than reductions to lower rates because personal and business decisions regarding additional labor and investment, as well as relocation, are made at the margin—that is, based on how tax rates will affect the next dollar of income, not income already earned. High marginal rates reduce the payoff to additional work and business investment on the margin, resulting in fewer hours worked, lower workforce participation, and fewer capital investments made by businesses.

Like the individual income tax rate, Wisconsin’s corporate income tax rate has also lost competitive standing over the last decade. At 7.9 percent, Wisconsin’s corporate rate was closer to the middle of the pack a decade ago (the 19th highest in the nation) but is now the 14th highest.

Consider neighboring Iowa, which has taken significant strides to improve its tax competitiveness over the past five years. Once the comprehensive reforms enacted in 2018 and 2022 are fully phased in, Iowa will have a more neutral tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. with a flat individual income tax rate of 3.9 percent (down from 8.98 percent) and a flat corporate income tax rate of 5.5 percent (down from 12 percent), along with the repeal of its inheritance taxAn inheritance tax is levied upon the value of inherited assets received by a beneficiary after a decedent’s death. Not to be confused with estate taxes, which are paid by the decedent’s estate based on the size of the total estate before assets are distributed, inheritance taxes are paid by the recipient or heir based on the value of the bequest received. , some sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. modernization, and other improvements to the tax code. These reforms have put Iowa on track to go from having the fifth-worst-structured tax code before 2018 to the 15th-best-structured tax code once these reforms are fully phased in.

Nearby Indiana, for 10 years in a row, diligently reduced its corporate income tax rate, lowering it from 8.5 percent in 2012 to 4.9 percent today. The Hoosier State already boasts a flat individual income tax rate of 3.23 percent, third lowest in the nation, but a 2022 law will drop the rate to 3.15 percent in 2023 and use future revenue growth to phase down the rate to 2.9 percent over time.

Even Illinois, a notoriously high-tax, high-spending state, has a flat individual income tax rate much lower than Wisconsin’s top rate. In 2020, Illinois voters soundly rejected a proposed constitutional amendment that would have allowed the legislature to implement a graduated-rate income tax structure with rates similar to Wisconsin’s.

Finally, this year in neighboring Michigan, legislators have passed tax relief legislation that includes reducing the flat individual income tax rate from 4.25 to 4 percent. It remains to be seen, however, whether any tax relief will be agreed upon between the Republican-controlled legislature and Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D).

While high income tax rates are Wisconsin’s most glaring tax policy problem, they are not the only issue holding Wisconsin back from a competitive tax code. The state also has a marriage penalty in its brackets that is imperfectly addressed with a married couple credit, a 3 percent “economic development surcharge” some businesses pay in addition to the 7.9 percent corporate income tax rate, and a nonneutral corporate income tax throwback rule that discourages certain multistate firms from originating sales out of Wisconsin. Wisconsin also continues to levy antiquated, nonneutral, and administratively burdensome taxes on certain forms of business personal property. These and other issues could all be addressed through comprehensive tax reform.

Given the strong surpluses Wisconsin has generated in recent years and the continued revenue growth the state is expecting in the future, the Badger State is in a good position to begin tackling comprehensive reform. In fact, state forecasters are projecting Wisconsin will end the current budget cycle with more than $3.8 billion in surplus revenue above and beyond what the state plans to spend.

Next year, policymakers should consider using part of this sizable revenue cushion to provide tax relief in a structurally sound way while dedicating a portion of future revenue growth to flattening, consolidating, and reducing income tax rates and adopting other pro-growth reforms that will make the state more attractive to individuals and businesses alike. Many of the states that have recently enacted reforms have used tax triggers to ensure any future rate reductions are implemented only when the state is in strong fiscal standing and has more than enough revenue to do so. Wisconsin should consider a similar approach.

While Wisconsin has long been one of the highest-tax states in the nation, that distinction is increasingly detrimental as businesses and individuals enjoy increased economic and geographic mobility. Wisconsin policymakers should therefore consider dedicating a portion of the existing budget surplus, plus a portion of future revenue growth, toward improving the structure of the tax code in a manner that will generate stronger economic growth in the future while improving Wisconsin’s competitive standing compared to regional and national peers.

Share this article