New Jersey residents are generally aware that they live in a high-taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. state. The state ranks 50th in our State Business Tax Climate Index, has one of the highest individual income taxes in the country, and property taxes are so hefty that a Jersey journalist once told me that “complaining about property taxes is the unofficial state pastime.”

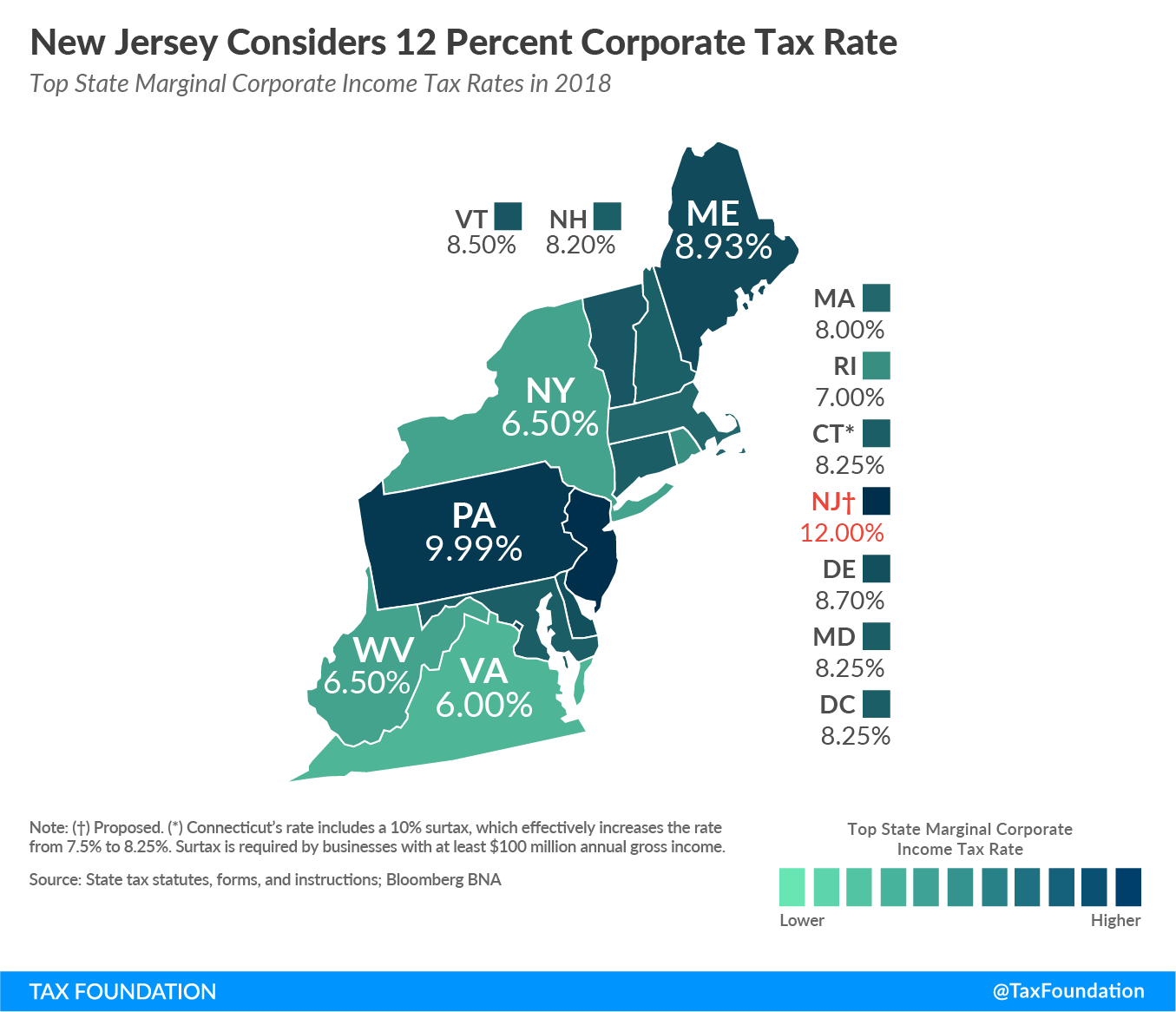

So it may come as a surprise to state residents that legislative leadership in the state is considering a sizable increase in the state’s corporate tax rate this year, from its current 9 percent to 12 percent. If enacted, New Jersey would tie Iowa for the highest rate in the country. Perhaps more importantly, though, Jersey’s corporate rate would be higher than neighbor Pennsylvania (9.99 percent) and almost double that of New York (6.5 percent).

The espoused reasoning of the tax increase is designed to appeal to emotion: corporations are getting a tax cut at the federal level, so the state of New Jersey is going to reclaim for itself some of what that tax cut would have been.

However, this reasoning is misguided. Choosing this moment to raise corporate taxes ignores the landscape created by the newly-enacted 21 percent federal corporate rate. While corporations are indeed getting a tax cut relative to last year, New Jersey’s state tax policies are still evaluated by prospective businesses relative to 49 other states. A few states (e.g., Iowa, Idaho, Georgia, and Maine) are already using state revenue windfalls created by federal tax reform as an opportunity to lower corporate and individual income tax rates.

If the federal corporate tax reform works as intended, it will induce additional capital investment into the United States. If we know the growth is coming, the question is where. It is less likely to come in New Jersey if similar investments face half the corporate tax in New York.

This new landscape is not going away in a few years either. In fact, one of the notable state tax trends in the last decade has been consistent reductions in state corporate taxes. Why? There appears to be a general consensus in state policy circles that corporate capital is highly mobile; that is, if you tax it too much, it tends to move (and then you can’t get any revenue out of it).

At the state level, the corporate tax has been tailored in from all sides, as states continue to trim away at collections by moving toward single sales factor apportionment, enacting sizable credits for certain economic activity, and of course by cutting top-line rates.

What’s more, corporate taxes make up such a small portion of total state and local tax collections (just 3.7 percent in FY 2014) that cutting state corporate rates can be an attractive economic tool to boost growth without sacrificing lots of revenue that legislators use to pay for government services.

So while there might be emotional appeal to this proposal, the economic justification isn’t there. New Jersey legislative leadership is decidedly moving in a misguided direction with this tax idea.

Share this article