President Biden expanded and fundamentally changed the Child Tax Credit (CTC) for one year in the American Rescue Plan (ARP) passed in March 2021. Policymakers are now deciding the future of the expansion as part of the proposed reconciliation package, but a wide range of estimates for the effects of a permanent expansion is confusing the debate.

The ARP made the maximum CTC more generous, increased the maximum age of qualifying children, and provided the credit in monthly payments occurring in the second half of 2021. It also made the full amount of the credit fully available to lower-income households, removing the incentive to work—or the participation bonus—that was built into the prior structure of the credit.

The expansion of the credit will significantly reduce the number of children living in poverty, which may have positive long-run effects, but the expansion will have unintended consequences too. In particular, removing the participation bonus and increasing marginal tax rates on earned income reduces incentives to work, which may partially counteract the reduction in poverty.

Substitution effects and income effects: What’s the difference?

The ways in which changing the CTC could impact decisions about work are often conflated. Clearing up the differences between income effects and substitution effects can help shed light on why analyses indicate a loss of jobs among recipients if the expanded CTC continues.

One way a policy change can affect labor supply decisions is through an income effect. The idea is that if people have more money overall, they might choose to work less and enjoy more leisure time. The literature, however, indicates that income effects are usually pretty small and might even be zero.

The other way a policy change can affect labor supply decisions is through a substitution effect. The idea is that if people see decreased compensation for an additional hour of work, for instance, through higher marginal taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rates, work becomes less valuable than leisure and they might choose to work less. Substitution effects hold up in the literature, and the research indicates they are greater than income effects.

For example, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), in estimating the responsiveness (or “elasticity”) of labor supply to a change in after-tax incomeAfter-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. , uses a central estimate of -0.05 for income effects and a range of 0.15 to 0.35 for substitution effects (for primary earners and varies with income level). Under a 2 percentage point increase in tax rates on all income, the substitution effect would reduce the labor supply by 0.70 percent and the income effect would increase the labor supply by 0.13 percent, for a net decrease of 0.57 percent.

What’s that have to do with the Child Tax Credit?

It’s important to clarify which effect is at play when discussing how the CTC expansion might affect decisions about work.

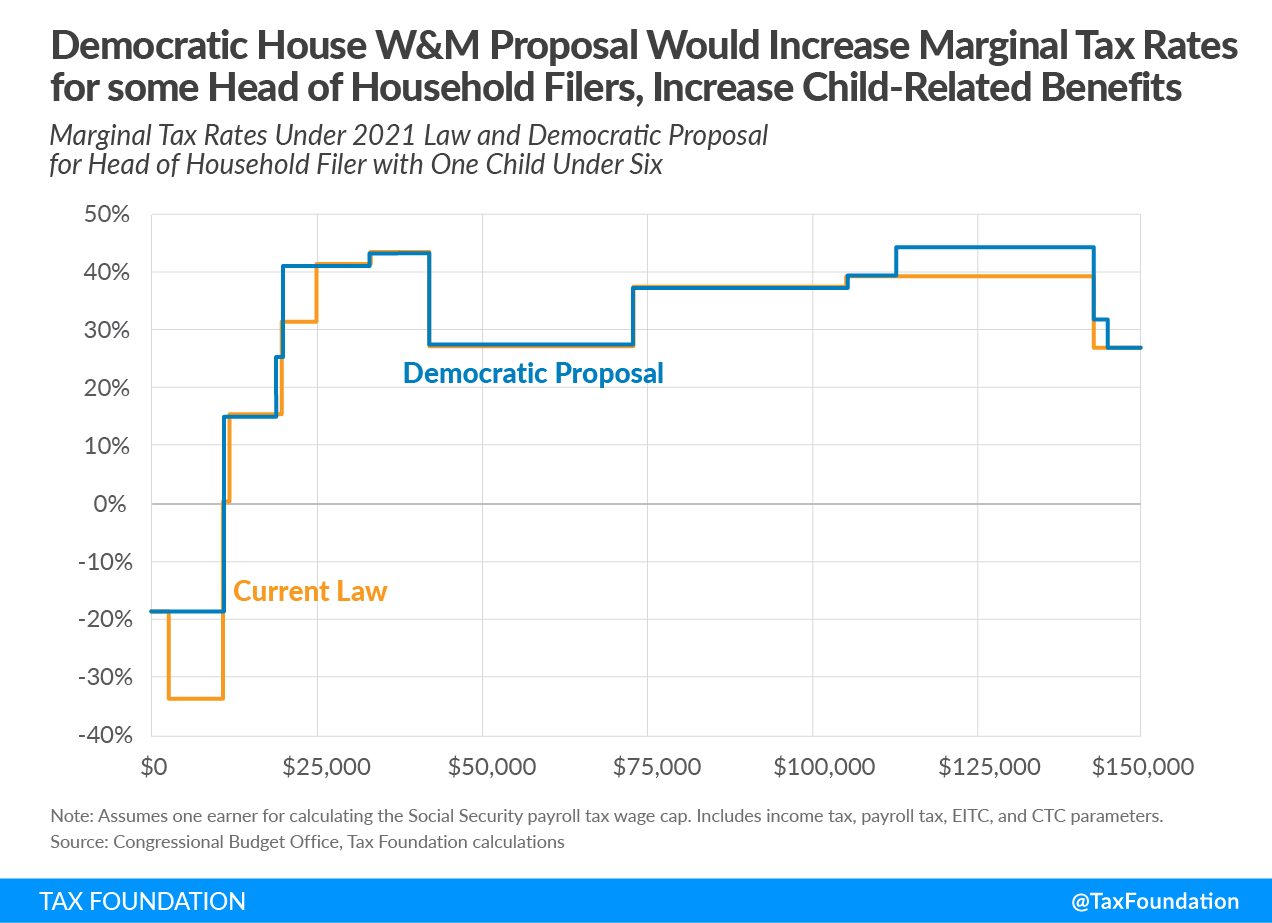

Until the changes made in 2021, the CTC included a “participation bonus” for working, as eligibility depended on having earned income, and the credit phased in with earned income, reducing marginal tax rates for people along the phase-in range. But the new structure eliminates the participation bonus and increases marginal tax rates on low-income households along the phase-in range (see the blue line compared to the gold line in the accompanying chart). Therefore, we should expect to see a substitution effect in response to the higher marginal tax rates and elimination of the participation bonus.

Relatedly, in a review of the literature, the CBO finds “evidence that low-income workers have higher elasticities of labor supply than other workers, especially in the component of their labor response that reflects movement in and out of the workforce.”

A new paper from University of Chicago economists estimated that relative to current policy, the proposed extension of the ARP CTC would reduce the returns to work by at least $2,000 per child for families with children by removing the participation bonus. When accounting for the labor supply response to the reduced returns to work, the authors estimate that 1.5 million workers would exit the labor force. Altogether, they estimate poverty would fall less than other estimates have suggested due to the labor supply response, and deep poverty in particular would not fall at all.

While the estimates may seem implausibly large, when the National Academy of Sciences modeled a proposal to expand the Earned Income Tax CreditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. (EITC), it used a similar estimate of labor supply response. As both the EITC and CTC generally target the same populations, it is consistent to assume that these populations will respond similarly to both policies. And the preponderance of evidence suggests the EITC boosts labor supply for many workers by increasing the returns to work.

What is the time frame for labor to respond to changes in marginal tax rates?

According to the CBO, it depends on such factors as how quickly workers learn about changes in after-tax marginal wages and whether policy changes are subtle or salient. The literature tends to use a period of three years to estimate permanent labor supply responses to policy changes.

A forthcoming paper titled “Labor Supply Responses to Learning the Tax and Benefit Schedule” explains that while a three-year period is typically used to account for “sluggishness in behavioral adjustments to tax changes,” significant responses continue to occur as much as eight years after the policy change. In other words, it can take time, but as people learn, people respond.

As such, we generally should not expect to see a significant labor supply response right now to this year’s expanded CTC, since the policy is new, complicated, and temporary. Consider a June 2021 survey finding 29 percent of low- to moderate-income households had heard little to nothing about the credit.

If the expanded CTC policy is extended or made permanent, we would expect people to learn more about how the changes affect their situation and respond accordingly in the medium term. For example, if the estimate of 1.5 million workers exiting the labor force took eight years, that would mean an average of 187,500 jobs lost per year.

But don’t other countries have policies like this?

Proponents often cite studies of policy changes in other countries in an attempt to inform the policy conversation in the U.S. But it’s important to determine which evidence is relevant—and which isn’t.

For instance, many point to Canada’s 2015 expansion of its universal childcare credit and a new benefit introduced in 2016 to argue that the CTC expansion in the U.S. would only have limited effects on labor supply of single mothers. The Canadian proposals are not a useful comparison to the changes being considered in the U.S. because none of the Canadian policies was conditioned on work.

In other words, unlike the reforms being considered in the United States, the reforms in Canada did not remove a participation bonus and so would not lead to a substitution effect. Instead, the Canadian child benefit could only produce an income effect, which research indicates is small. Similarly, the University of Chicago paper discussed above also estimates a small income effect for the proposed CTC expansion in the U.S.

What about other effects from the expanded Child Tax Credit?

Many proponents of the CTC expansion will point to studies showing that spending on children can have positive outcomes on their well-being much later in life, and that any evaluation of the policy should capture this spectrum of benefits.

The Center on Poverty & Social Policy at Columbia University estimated, for example, that an increase of $1,000 in household income could boost children’s future earnings by $1,129 per year, based on estimates ranging between $651 and $2,320 per year. Those estimates, however, rely primarily on studies of food stamps in the 1960s and 1970s and WWI military pensions for mothers in the 1920s and 1930s. As the welfare state was much smaller during past periods, it is not clear how much we can extrapolate to conclude that a CTC expansion would have similar effects in the future. Another estimate cited in the Center’s study looks at the EITC, a program similar to the CTC, and finds the benefit is considerably smaller, at $660 per year for a $1,000 transfer.

Another drawback is that such studies don’t always provide a complete accounting for the costs and benefits of the expanded CTC in that they often exclude the substitution effects discussed above and the taxes that would be required to finance the expanded CTC in the long run.

As lawmakers weigh whether to reintroduce a participation bonus to the expanded child tax credit, or make other changes to its structure in reconciliation, they should keep in mind how the CTC can affect labor supply decisions and the implications for the credit’s impact on poverty reduction.

Share this article