The UK government has made “leveling up”—a push to boost economic performance in less thriving regions of the UK—one of its top policy priorities. The recent introduction of a UK super-deduction for capital investments in plant and equipment will likely contribute to this goal. Higher capital allowances for plant and equipment disproportionally help capital-intensive industries such as manufacturing, which tend to be located in the UK’s less prosperous regions. However, this comes after years of limiting capital allowances—a policy choice that potentially played a factor in widening the regional divide in the first place.

As part of the 2021 Budget, the UK introduced a 130 percent super-deduction for plant and equipment for the next two years, meaning that businesses can take a deduction amounting to 130 percent of the costs in the year the investment is made. For example, if a business buys a $10,000 machine in 2021, it gets to deduct $13,000 from its revenues in 2021. Prior to this change, investments in machinery had to be written off over several years at a rate of 18 percent of the remaining value. Once the UK super-deductionA super-deduction is a tax deduction that permits businesses to deduct more than 100 percent of their eligible expenses from their taxable income. As such, the super-deduction is effectively a subsidy for certain costs. This policy sometimes applies to capital costs or research and development (R&D) spending. expires in 2023, it will reverse to the old system.

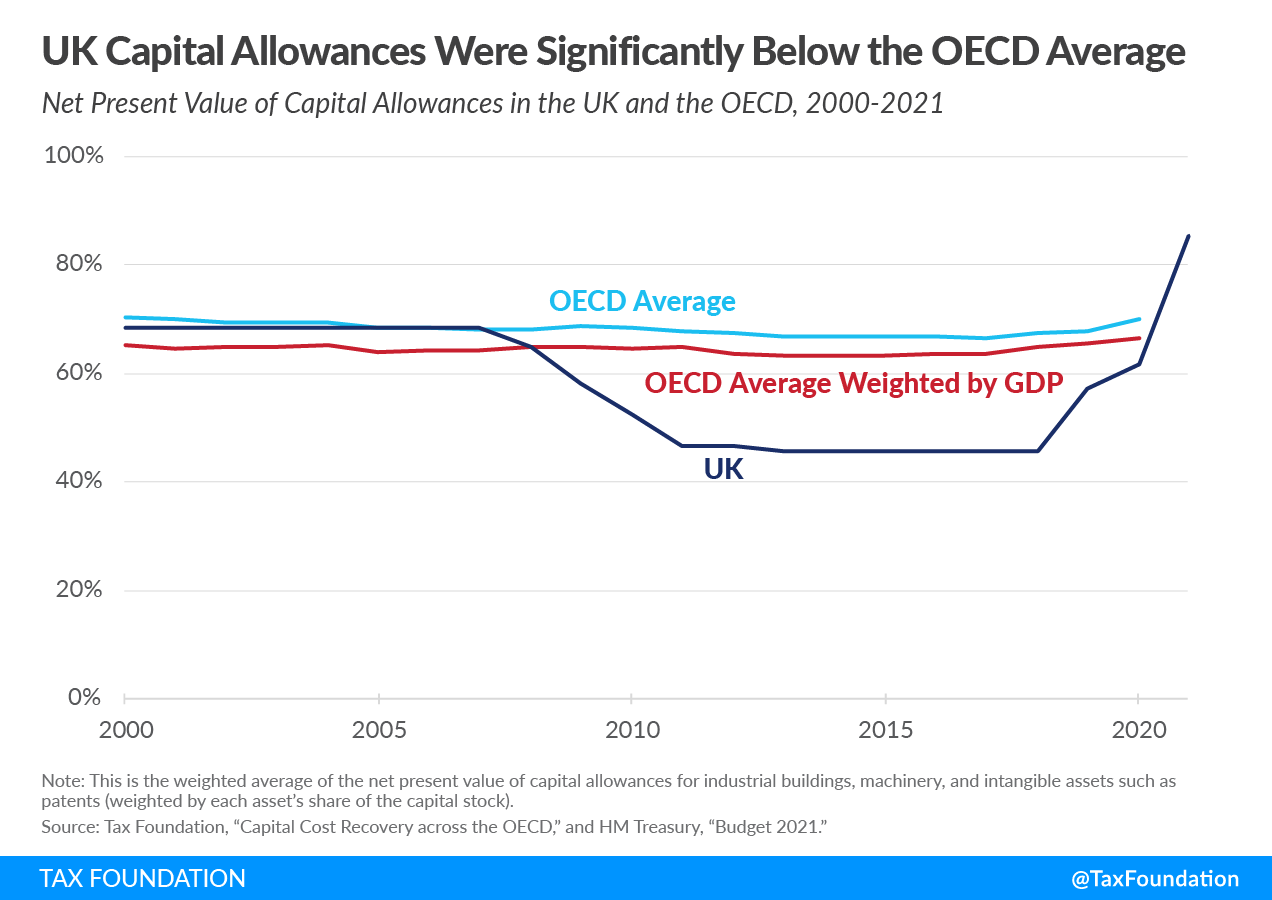

The corporate changes made in the 2021 Budget further reverse a policy choice made over a decade ago. In the late 2000s, the UK began to limit its capital allowances for equipment and completely phased out capital allowances for industrial buildings. Investing in these assets became increasingly costly because businesses could not—or only partially—deduct the investment costs. Measured in real terms, the UK’s capital allowances fell well below the OECD average, making capital investments in the UK not only more expensive for domestic firms but also relatively unattractive for foreign investors.

Roughly at the same time, however, the UK considerably lowered its corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate—from 30 percent in 2000 to the current level of 19 percent (an increase to 25 percent is scheduled for 2023). Limiting capital allowances was intended to offset some of the taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. revenue losses resulting from the cut in the corporate tax rate. A similar trend could be observed in the UK in the 1980s and 1990s: In the early 1980s, machinery could be fully written off in the first year and buildings had a similarly generous treatment, while the corporate tax rate was above 50 percent.

This trade—limited capital allowances for a lower statutory corporate tax rate—may have reduced overall tax revenue losses. However, as limited capital allowances disproportionally harm capital-intensive industries such as manufacturing that tend to be located in the northern part of the country, it potentially played a factor in widening the geographical divide in economic performance—the very issue the government now wants to address with its leveling up agenda and its super-deduction. Since capital investments play a less significant role for the disproportionally south-based service sector, limiting capital allowances proved to be less of an issue for that sector, while lower corporate tax rates boosted its after-tax profits.

The super-deduction is a temporary policy and is set to expire in 2023. Particularly larger investments require a considerable amount of lead time, which potentially limits the number of new (currently unplanned) investment projects businesses will be able to make before 2023. Some businesses may shorten the timeline for investments that are already under consideration. For example, an investment project that was scheduled for 2024 may be done in 2023 to take advantage of the super-deduction. However, this would merely change the timing—not the total amount—of capital investment.

Making the super-deduction—or a more moderate and neutral 100 percent deduction—permanent would likely boost long-term investment more than the current temporary policy does. In 2019, the UK had the second lowest level of investment as a percent of GDP among OECD countries: 17.3 percent compared to an OECD average of 21.7 percent, and only ahead of Greece. A permanent super- or full-deduction would likely not only help narrow the regional divide but also raise the national investment level.

In addition to the broad-based 130 percent super-deduction, the 2021 Budget calls for the establishment of eight so-called Freeports—designated areas where businesses will benefit from more generous tax reliefs, simplified customs procedures, and wider government support. Businesses within these Freeports will be able to claim a 10 percent capital allowanceA capital allowance is the amount of capital investment costs, or money directed towards a company’s long-term growth, a business can deduct each year from its revenue via depreciation. These are also sometimes referred to as depreciation allowances. for structures and buildings (instead of the nationwide rate of 3 percent) and a 100 percent capital allowance for plant and equipment. Both measures are temporary, expiring in 2026.

Corporate tax policy should generally be permanent and neutral—not favoring one business over another based on size or location. A nationwide full deduction after the super-deduction expires would thus be preferable, as it considerably reduces taxes on investment in every part of the UK and gives the capital-intensive industries in the northern part of the country a chance to catch up after decades of rising taxes on capital investment.