Senators Chris Murphy (D-CT) and Bob Corker (R-TN) yesterday called for a twelve-cent increase in the federal gasoline and diesel taxes. The increase would phase in over two years, bringing the taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. on ordinary gasoline up from 18.4 cents to 30.4 cents per gallon. From then on, the tax would be indexed to inflation. (The diesel tax would go from 24 cents a gallon to 36.)

This is a simple, straightforward bid to close the gap in the Federal Highway Trust Fund, which is set to run out of money this summer, and is about $170 billion short over the ten-year budget window.

The Federal Highway Trust Fund is funded through gasoline taxes because of a tax idea called the benefit principle. If the government is providing a service for “free,” that service frequently ends up overused. (There are few things more obviously overused than congested roads.) A way to solve this problem and provide revenue to create the service, simultaneously, is to levy a tax on something related to the service. To maintain highways, the federal government levies taxes on gasoline purchasers. Another solution would be to task the states with raising their own revenue for infrastructure – but that would probably need to be a more gradual process.

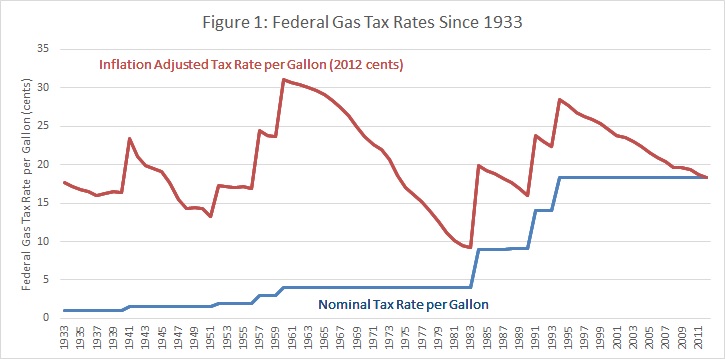

A problem with the gas taxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline. is that it has always been set in nominal terms – not adjusted for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. . The result is that its real value has bounced around quite a bit over the years. Tax Foundation Chief Economist Will McBride recently analyzed the issue:

The gas tax hasn’t risen since 1993, and since then the real value of the tax has eroded substantially. The proposal would raise the real value of the tax to approximately where its peak values have been in the past, and then inflation-index it.

We can also determine pretty well that the tax would raise the necessary revenue to close the shortfall. Gas tax revenue is highly predictable because demand for gas is very inelastic with respect to taxes – in other words, people mostly won’t change their behavior as a result of a 12 cent tax increase on a $3.75 gallon of gas. We can see this empirically from previous rises in the gas tax. The last two gas tax increases happened in the 1990s. The first was a 55% increase in the tax that created a 53% increase in revenue. The second was a 30% increase in the tax that created a 33% increase in revenue.

With this sort of simple revenue math, we can affirm with a reasonable degree of certainty that the tax will create the intended revenue. The Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Committee on Taxation have projected the results of a much larger gas tax increase of 35 cents, with the same inflation indexing. Their results were a $452 billion increase in revenue over the ten-year budget window. This tax increase would be a little over a third of the tax hike from that CBO scenario, and would produce a little bit over a third of the revenue – probably about the right amount to close the $170 billion shortfall.

The Murphy-Corker proposal would not raise taxes overall; they plan to offset the increased revenues with tax cuts elsewhere – possibly by making permanent some of the “tax extenders” – temporary provisions that face expiration from year to year.

All in all, this is the simple, by-the-book proposal for fixing the Highway Trust Fund shortfall. If the federal government wants $170 billion to spend money on highways, this is the way to raise the revenue. The proposal has the additional benefit of indexing the tax to inflation, such that the revenue remains more stable in the future.

Share this article