Download BACKGROUND PAPER No. 69: The Marketplace Fairness Act

Key Findings

- The Marketplace Fairness Act (MFA) would allow any state to require sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. collection by out-of-state retailers, if the state simplifies its sales taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. system.

- Sales taxes are paid by consumers, but are usually collected and remitted by retailers at significant cost.

- State taxation power is generally limited to individuals and businesses within the state’s borders, to prevent harm to the national economy from tax exporting.

- Some states are nonetheless passing “click through nexus” statutes and demanding out-of-state retailers collect sales tax, leading to extended litigation and uncertainty. Other states are working with the Streamlined Sales Tax Project for greater tax uniformity.

- A federal solution is needed and must allow states to collect sales tax on sales to their residents, eliminate unjustifiable tax distinctions between identical items, define the limits of state tax authority, and simplify the tax system to reduce compliance burdens.

- The MFA bill is in this vein but would benefit from software compatibility requirements, a blended tax rate option, limits to state auditA tax audit is when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) conducts a formal investigation of financial information to verify an individual or corporation has accurately reported and paid their taxes. Selection can be at random, or due to unusual deductions or income reported on a tax return. authority, and federal jurisdiction over disputes.

- “Hybrid Origin-Sourcing” (HOS), while appealing in its simplicity, would require fundamentally restructuring how sales taxes work, confusing consumers and posing immense administrative and legal obstacles.

- Because HOS allows states to tax consumers without minimum contacts with the state, it likely would violate the U.S. Constitution’s Due Process Clause.

Executive Summary

In May 2013, the U.S. Senate voted 69 to 27 to approve the Marketplace Fairness Act (MFA), a bill that would allow a state to require sales and use tax collection by out-of-state retailers if the state adopts specified simplifications for its sales tax system. Currently, retailers are only required to collect sales taxes in states where they have a physical presence of property or employees. This geographic limitation on the scope of state tax power, while not new, has come under pressure due to the growing size of Internet retail and the resultant disparity in tax treatment between goods purchased online and goods purchased at brick-and-mortar stores.

The U.S. House of Representatives has yet to consider the bill, and its Judiciary Committee has recently engaged in a search for alternatives to the MFA approach.[1] One alternative, a “hybrid origin-sourcing” (HOS) approach, would significantly transform the structure of sales taxes. Meanwhile, an increasing number of states are defying constitutional restrictions and ordering retailers to collect sales and use taxes, sparking extensive litigation and economic uncertainty. Another group of states has adopted the Streamlined Sales Tax Agreement, which held promise as a potential solution but has struggled to win over most states.

The HOS approach has appeal due to its simplicity but has a number of insurmountable problems, including the difficulty of defining origin and consequent tax arbitrage opportunities, the economic and structural difficulties of transforming the sales tax into a business tax, the unlikelihood of an interstate compact structure to achieve uniformity, taxation without representation for many consumers, the retention of economically unjustifiable tax distinctions for similar items purchased in the same state, and the lack of needed simplifications to the sales tax system. Most problematically, the HOS proposal likely violates the Due Process Clause of the U.S. Constitution because it imposes state tax authority on taxpayers who lack the minimum contacts required for a state to assert personal jurisdiction. HOS may also exceed Congress’s power under the Interstate Commerce Clause by overly coercing states to alter internal tax policies unrelated to interstate commerce.

Keeping the sales tax up to date with the modern economy is important for the states and brick-and-mortar retailers, just as making multistate sales tax collection as seamless and simple as possible is important for Internet retailers and the national economy as a whole. The MFA approach—giving states limited additional authority to collect existing taxes, so long as the state adopts meaningful simplifications to their sales tax system—strikes the right balance. While key simplifications are needed in the current MFA draft, these can be added more easily than resolving the complications associated with constructing a brand new sales tax system based on hybrid origin-sourcing.

What Are Sales and Use Taxes?

State Sales Taxes

Taxes on specific transactions are as old as antiquity and have always been a common feature of federal, state, and local public finance in the United States. But general state sales taxes did not come about until the collapse in property tax revenues during the Great Depression, with Mississippi being the first to adopt the tax in 1930, at a 2 percent rate. By 1940, 22 states and Hawaii had adopted sales taxes. Today, 45 states and the District of Columbia impose sales taxes; only Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon have no statewide sales tax. In 2013, taxpayers paid $259 billion in state sales taxes, amounting to 30 percent of all taxes collected by state governments.

Local Sales Taxes

Local sales taxes exist in 38 states, with total collections of $70 billion in 2013.[2] Altogether there are a total of 9,998 different sales tax jurisdictions in the United States (see Figure 1 for a map of jurisdictions by state). In most cases, local sales taxes are collected at the same time and on the same base as the state sales tax, though there are exceptions. Many local jurisdictions also have different sales tax rates for certain purchases, such as prepared food or car rentals. The states with the highest combined state and average local sales taxes are Tennessee (9.45 percent), Arkansas (9.19 percent), Louisiana (8.89 percent), Washington (8.88 percent), and Oklahoma (8.72 percent). The five states with the lowest average combined rates are Alaska (1.69 percent—there is no state sales tax, only local sales taxes), Hawaii (4.35 percent), Wisconsin (5.43 percent), Wyoming (5.49 percent), and Maine (5.50 percent). A table of current state and average local sales tax rates is listed in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Sales Tax Jurisdictions by State

Figure 2: State and Average Local Sales Tax Rates by State, as of Jan. 1, 2014

| State | State Tax Rate | Rank | Avg. Local Tax Rate (a) | Combined Tax Rate | Rank | Max Local |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 4.00% | 38 | 4.51% | 8.51% | 6 | 7.00% |

| Alaska | None | 46 | 1.69% | 1.69% | 46 | 7.50% |

| Arizona | 5.60% | 28 | 2.57% | 8.17% | 9 | 7.125% |

| Arkansas | 6.50% | 9 | 2.69% | 9.19% | 2 | 5.50% |

| California (b) | 7.50% | 1 | 0.91% | 8.41% | 8 | 2.50% |

| Colorado | 2.90% | 45 | 4.49% | 7.39% | 15 | 7.10% |

| Connecticut | 6.35% | 11 | None | 6.35% | 31 | |

| Delaware | None | 46 | None | None | 47 | |

| Florida | 6.00% | 16 | 0.62% | 6.62% | 29 | 1.50% |

| Georgia | 4.00% | 38 | 2.97% | 6.97% | 23 | 4.00% |

| Hawaii (c) | 4.00% | 38 | 0.35% | 4.35% | 45 | 0.50% |

| Idaho | 6.00% | 16 | 0.03% | 6.03% | 36 | 2.50% |

| Illinois | 6.25% | 12 | 1.91% | 8.16% | 10 | 3.75% |

| Indiana | 7.00% | 2 | None | 7.00% | 21 | |

| Iowa | 6.00% | 16 | 0.78% | 6.78% | 27 | 1.00% |

| Kansas | 6.15% | 15 | 2.00% | 8.15% | 12 | 3.50% |

| Kentucky | 6.00% | 16 | None | 6.00% | 37 | |

| Louisiana | 4.00% | 38 | 4.89% | 8.89% | 3 | 7.00% |

| Maine | 5.50% | 29 | None | 5.50% | 42 | |

| Maryland | 6.00% | 16 | None | 6.00% | 37 | |

| Massachusetts | 6.25% | 12 | None | 6.25% | 33 | |

| Michigan | 6.00% | 16 | None | 6.00% | 37 | |

| Minnesota | 6.875% | 7 | 0.31% | 7.19% | 18 | 1.00% |

| Mississippi | 7.00% | 2 | 0.004% | 7.00% | 20 | 0.25% |

| Missouri | 4.225% | 37 | 3.36% | 7.58% | 14 | 5.45% |

| Montana (d) | None | 46 | None | None | 47 | |

| Nebraska | 5.50% | 29 | 1.29% | 6.79% | 26 | 2.00% |

| Nevada | 6.85% | 8 | 1.08% | 7.93% | 13 | 1.25% |

| New Hampshire | None | 46 | None | None | 47 | |

| New Jersey (e) | 7.00% | 2 | -0.03% | 6.97% | 24 | |

| New Mexico (c) | 5.125% | 32 | 2.14% | 7.26% | 16 | 3.5625% |

| New York | 4.00% | 38 | 4.47% | 8.47% | 7 | 4.875% |

| North Carolina | 4.75% | 35 | 2.15% | 6.90% | 25 | 2.75% |

| North Dakota | 5.00% | 33 | 1.55% | 6.55% | 30 | 3.00% |

| Ohio | 5.75% | 27 | 1.36% | 7.11% | 19 | 2.25% |

| Oklahoma | 4.50% | 36 | 4.22% | 8.72% | 5 | 6.50% |

| Oregon | None | 46 | None | None | 47 | |

| Pennsylvania | 6.00% | 16 | 0.34% | 6.34% | 32 | 2.00% |

| Rhode Island | 7.00% | 2 | None | 7.00% | 21 | |

| South Carolina | 6.00% | 16 | 1.19% | 7.19% | 17 | 3.00% |

| South Dakota (c) | 4.00% | 38 | 1.83% | 5.83% | 40 | 2.00% |

| Tennessee | 7.00% | 2 | 2.45% | 9.45% | 1 | 2.75% |

| Texas | 6.25% | 12 | 1.90% | 8.15% | 11 | 2.00% |

| Utah (b) | 5.95% | 26 | 0.73% | 6.68% | 28 | 2.00% |

| Vermont | 6.00% | 16 | 0.14% | 6.14% | 34 | 1.00% |

| Virginia (b) | 5.30% | 31 | 0.33% | 5.63% | 41 | 0.70% |

| Washington | 6.50% | 9 | 2.38% | 8.88% | 4 | 3.10% |

| West Virginia | 6.00% | 16 | 0.07% | 6.07% | 35 | 1.00% |

| Wisconsin | 5.00% | 33 | 0.43% | 5.43% | 44 | 1.50% |

| Wyoming | 4.00% | 38 | 1.49% | 5.49% | 43 | 2.00% |

| D.C. | 5.75% | (27) | None | 5.75% | (41) |

Sales Tax Base

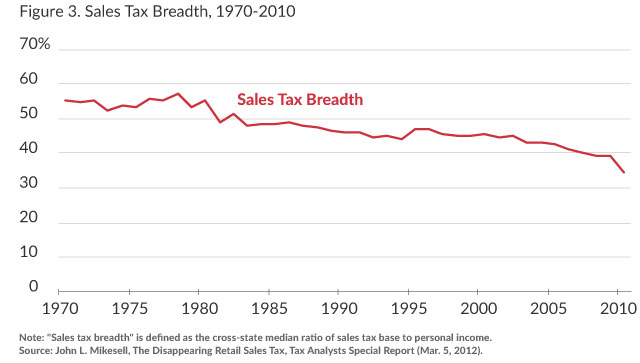

The base of the sales tax still resembles its origins as an emergency Depression measure. In all but three states, the tax is structured as a tax on the consumer’s purchase of tangible personal property not exempted, meaning that it is imposed on most goods and many business-to-business transactions but few services.[3] While this covered most sales occurring in Depression-era Mississippi, today’s services-oriented economy means the sales tax increasingly does not encompass most transactions (see Figure 3). Instead of broadening the base to generate consistent revenues, states have instead generally raised sales tax rates over time. Many states have actually added more exemptions to the tax, for items such as prescription drugs (43 states plus DC), groceries (37 states plus DC), and clothing (6 states).

Use Taxes

Use taxes were enacted as complements to sales taxes not long after their introduction. While the sales tax is owed for purchasing an item, the use tax is owed for using an item where sales tax has not been paid. States introduced use taxes out of concern that taxpayers would avoid sales taxes by purchasing goods in states with lower or no sales tax instead of purchasing them in state and paying tax. The use tax thus creates a tax obligation for consumers who do this, and all states with a sales tax also have a use tax with the same rate as the sales tax.[4] However, because the use tax requires self-reporting and payment by the consumer instead of collection at point of sale by the retailer, use tax compliance is very low except for large purchases or business purchases susceptible to state audit.[5] The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the use tax as a valid exercise of state tax power in 1937.[6]

Vendor Compensation

Even though the tax is legally owed by the consumer, all states require retailers to collect the tax on the consumer’s behalf and remit the money to the government. This significantly reduces governments’ costs of sales tax administration, while increasing the compliance burden for retailers. One leading study found that annual business sales tax compliance costs were not insignificant, amounting to 3.09 percent of sales tax collections and ranging from 2.17 percent for large retailers to 13.47 percent for small retailers.[7] To partly offset these billions of dollars in costs absorbed by sellers, half the states compensate vendors by allowing them to keep a small portion of sales tax collections, totaling some $1 billion per year.

Estimates of Uncollected Revenue

Americans spent about $263 billion in Internet retail purchases in 2013, a growth of 15 percent over the year before and comprising about 6 percent of the $4.5 trillion all retail sales.[8] The growth rate has been fairly steady and it is likely Internet commerce will continue to grow as a share of our retail industry.

States are understandably interested in knowing how much revenue could be collected if they could require sales tax collection on Internet commerce. Three states have passed legislation canceling tax increases or cutting taxes if the federal Marketplace Fairness Act is passed.[9] But revenue estimates are difficult to make with certainty because one must guess both how much Internet commerce could be taxed and how much is currently untaxed. (Some percentage of Internet sales taxes are actually collected because of retailer physical presence, voluntary reporting of business purchases, or voluntary vendor collection by SSTP vendors.) In 2009, Professor William Fox at the University of Tennessee estimated that states would lose $11 billion in 2012 if they could not collect sales tax on Internet purchases, and this became the leading source of revenue estimates by virtue of being the only one.[10]

The Fox study estimates have proven to be overstated by four- or five-fold based on subsequent actual collections experience in states that have been able to tax a large share of Internet purchases (such as those by Amazon.com). California reported $96 million in new online sales collections in the last quarter of 2012, its first year after reaching a deal with Amazon.com that resulted in the online seller collecting tax. However, this was far short of the $457 million each quarter that the Fox study estimated.[11] New York, with its law collecting tax on online sales while being appealed, collected $360 million through February 2012, again short of the $2.5 billion estimated by the Fox study.[12] Economic consultant Jeff Eisenach produced scaled-down estimates of states’ sales tax collection potential in 2013, pegging it at $3.9 billion nationwide.[13]

While it is true that state tax collections will increase if a federal bill is passed, states relying on the Fox study numbers risk writing excessive revenue expectations into their budget plans.[14] States should therefore act cautiously with respect to spending the new revenue when a federal bill is enacted.

What Is the Quill Physical Presence Nexus Rule?

U.S. states engaged in a trade war with each other after independence in the 1780s. Coastal states imposed hefty taxes on goods going to interior states and vice versa. This rivalry threatened to strangle the economy, so leaders called the Constitutional Convention.[15] The document they produced—the U.S. Constitution we still use today—stopped this trade war and ushered in decades of prosperity. It did so by giving the federal government the power to stop any state government that reaches beyond its borders to harm interstate commerce.[16] For a century and a half, the rule was a simple one: states cannot tax interstate commerce at all.[17]

That complete ban gave way in the 1950s. As interstate commerce grew sharply, states complained that in-state businesses engaged in interstate commerce still used services like schools and police, and the Supreme Court’s holdings became inconsistent with each other.[18] In 1977, the Supreme Court finally swept aside two centuries of increasingly unworkable precedent and formally authorized states to tax businesses engaged in interstate commerce, but only if four conditions were met:

- there is a substantial connection, or nexus, between the state and the taxpayer;

- the tax does not discriminate against interstate commerce;

- the tax only applies to the fairly apportioned share of activity happening within the state; and

- the tax is fairly related to services provided to the taxpayer by the state.[19]

The element of this test, known as the Complete Auto test, most relevant to the Internet sales taxAn internet sales tax is a sales and use tax collected and remitted on remote sales, many done online. In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states could impose such obligations on sellers lacking physical presence in the state, vastly expanding the reach of these collection and remittance requirements. issue is the first one, “substantial nexus.”[20] In the National Bellas Hess case in 1967, the Supreme Court had held that states could not require tax collection from an out-of-state business who communicated with customers solely by common carriers like the U.S. mail or an independent delivery company (in that case, a catalog mailer).[21] The Court expressed strong concerns about the compliance burdens that would be imposed on interstate sellers forced to comply with every sales tax system in the country:

[I[f the power of Illinois to impose use tax burdens upon National were upheld, the resulting impediments upon the free conduct of its interstate business would be neither imaginary nor remote. For if Illinois can impose such burdens, so can every other State, and so, indeed, can every municipality, every school district, and every other political subdivision throughout the Nation with power to impose sales and use taxes. The many variations in rates of tax, in allowable exemptions, and in administrative and recordkeeping requirements could entangle National’s interstate business in a virtual welter of complicated obligations to local jurisdictions with no legitimate claim to impose “a fair share of the cost of the local government.[22]

Additionally, the physical presence rule comports roughly with what economists call the “benefit principle,” the idea that the taxes one pays should be a rough proxy for the government services that one consumes.[23] State spending overwhelmingly, if not completely, is meant to benefit the people who live and work in the jurisdiction. The primary beneficiaries of education, health care, roads, and police protection are state residents. The benefit principle means that residents should be paying taxes where they work and live, and jurisdictions should not tax those who don’t work and live there.

A month after the Complete Auto decision in 1977, the Court clarified that this physical presence standard was still the rule for determining substantial nexus for the collection of sales and use taxes, rejecting a “slightest presence” standard.[24]

While states appreciated the extension of their power to tax in-state businesses engaged in interstate commerce, they chafed at the limitations imposed by the physical presence rule, which restricted them from taxing out-of-state businesses selling into the state. Concluding that the physical presence rule reaffirmed in National Bellas Hess was outdated due to changes in technology, North Dakota in the early 1990s ordered the out-of-state Quill Corp. to collect the state’s sales tax based on an “economic nexus” standard. Quill, a mail order office supply vendor, had no property or employees in North Dakota but did sell $1 million worth of supplies to 3,000 customers in the state, delivered 230,000 catalogs and flyers into the state, and made sales calls and advertised in national publications with North Dakota subscribers.

The Quill case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court and they strongly reaffirmed the physical presence rule for sales and use tax collection.[25] The Court held that the physical presence rule “firmly establishes the boundaries of legitimate state authority to impose a duty to collect sales and use taxes and reduces litigation concerning those taxes.” The Court did clarify that the physical presence rule is based on the Interstate Commerce Clause, one of the few constitutional provisions where Congress may change a Supreme Court interpretation merely by passing a statute.[26] State tax laws must also satisfy the Due Process Clause, which Congress cannot change, but the standard for that can be met by actions other than physical presence. The Quill case remains the Supreme Court’s last word on sales tax nexus to date, which is why physical presence is sometimes termed the Quill rule.

What Problematic Actions Are States Taking in the Meantime?

Thirteen states have adopted statutes to expand sales and use tax collection authority over remote (out-of-state) sellers in recent years.

The New York “Amazon” Tax Law

New York’s statute, adopted in 2008, expands the definition of sales solicitation to include an out-of-state seller who “enters into an agreement with a resident of this state under which the resident, for a commission or other consideration, directly or indirectly refers potential customers . . . to the seller” and such sales exceed $10,000 per year.[27] Because the Internet transcends state borders, New York’s law will apply both to retailers that target sales to New York residents and to retailers who sell generally to everyone on the Internet, and may or may not end up selling to New Yorkers. The New York Court of Appeals, the highest court in the state, has determined that the state need not prove that solicitation happened but can just assume it did and consequently find nexus, unless the retailer proves it didn’t.[28]

If, however, a seller presents “proof that the resident with whom the seller has an agreement did not engage in any solicitation in the state on behalf of the seller” during that year period, the seller will not be considered engaged in solicitation. While this “rebuttable presumption” or “safe harbor” is impossible because it requires somehow proving that someone else didn’t do something on the Internet, the New York Court of Appeals upheld the statute primarily because the rebuttable presumption at least theoretically permits taxpayers to prove solicitation did not occur.[29] The Court of Appeals was also reassured that the Department of Revenue voluntarily chose not to enforce the “other consideration” language in the statute, which would necessarily encompass this passive advertising activity.[30]

Under U.S. Supreme Court precedent, a company can be found to be physically present in a state if it either (1) has in-state employees, even if these employees do not engage in solicitation or (2) uses in-state independent contractor solicitors, if this use is significantly associated with the company’s ability to maintain an in-state market and results in a substantial flow of goods into the state. The New York statute conflates these two standards, permitting a finding a physical presence when the company uses in-state independent contractors, even if they do not engage in solicitation, so long as it results in a relatively modest ($10,000 per year) level of sales, and even if this level of sales is immaterial to the company’s market in the state.[31] In December 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear a case addressing the constitutionality of the New York law.

Other States

Following New York’s 2008 enactment of this “click-through nexus” or “Amazon affiliate nexus” statute, other states have followed with similar enactments:

- North Carolina in 2009 adopted an identical statute with the rebuttable presumption language and the $10,000 threshold.[32]

- Rhode Island in 2009 adopted a statute with the rebuttable presumption language and a lower $5,000 threshold.[33]

- Arkansas in 2011 adopted a statute with the rebuttable presumption and a $10,000 threshold.[34]

- Vermont in 2011 adopted a statute with the rebuttable presumption, a $10,000 threshold, and a further requirement that it not take effect until similar legislation passes fifteen other states.[35]

- California in 2012 adopted a statute with the rebuttable presumption, a $10,000 threshold, and a further requirement that the out-of-state seller have national sales of at least $1 million.[36]

- Georgia in 2012 adopted a statute with the rebuttable presumption and a higher $50,000 threshold.[37]

- Maine in 2013 adopted a statute with the rebuttable presumption and a $10,000 threshold.[38]

- Minnesota in 2013 adopted a statute with the rebuttable presumption and a $10,000 threshold.[39]

While these nine states[40] have statutes that at least theoretically allow taxpayers to rebut the presumption that they are physically present in the state due to compensated referral agreements with in-state affiliates, three states have enacted statutes that make the presumption that in-state solicitation occurred to be irrefutable:

- Connecticut in 2011 adopted a statute with a $2,000 threshold and no rebuttability.[41]

- Illinois in 2011 adopted a statute with a $10,000 threshold and no rebuttability.[42] This statute is currently under review by the Illinois Supreme Court after being struck down by a lower court.[43]

- Texas in 2011 adopted a statute expanding the definition of “retailer” to include any out-of-state seller who “derives receipts” from sales in the state and any out-of-state seller who delivers items to customers in the state.[44] The statute has no minimum threshold and no rebuttability. The Texas Comptroller’s office has advised that it will not apply the statute to out-of-state sellers using common carriers to deliver products into the state, although the statute does encompass such activity.[45]

The New York courts upheld their version of the statute only because taxpayers may rebut the presumption of attributional nexus. The Connecticut, Illinois, and Texas statutes would not be valid under that rationale.

Colorado Warning Law

Additionally, Colorado in 2010 enacted a “warning law” requiring Internet retailers to notify customers that they owe use tax on their purchase and, more problematically, to report details of customers’ purchases to state authorities.[46] This statute faced a First Amendment challenge due to that latter requirement.[47] In July 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear an appeal in the case, on the question of whether the federal Tax Injunction Act bars federal jurisdiction over the case.

A similar scheme in North Carolina was ruled unconstitutional after a challenge by the ACLU.[48]

What Is the Streamlined Sales Tax Project and Why Has It Not Succeeded?

Established in 2000, the Streamlined Sales Tax Project (SSTP) is a joint effort by states and the business community to reduce sales tax compliance and administrative burdens. Its mission was to get states to adopt changes to their sales taxes to make them simple and uniform and then convince Congress or the courts to overrule Quill and allow use tax collection obligations on out-of-state companies. Twenty-four states representing 33 percent of the U.S. population have ratified the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement (SSUTA).[49]

However, this effort to balance state sovereignty with the need for simpler rules and remittance procedures has been severely hamstrung by the refusal of many large states to participate, including California, Illinois, New York, and Texas. While no state should be compelled to participate in SSTP, SSTP suffers because many states believe they assert expanded tax authority without the hard work required by SSTP, such as centralizing tax collection and auditing, reducing local sales tax complexity, adopting uniform definitions of items, and compensating vendors for administrative costs.

In an attempt to attract more member states, the SST Governing Board has focused increasingly on uniformity and not simplification. In many cases, the Project has enabled state sales tax complexity by permitting separate tax rates for certain goods, not addressing growing local tax jurisdiction complexity, and enabling states to retain parochial sales tax rules.[50]

What Is Included in and Missing from the MFA Bill?

Congress over time has passed a number of statutes limiting the scope of state tax authority on interstate activities, carefully balancing (1) the ability of states to set tax policies in line with their interests that allow interstate competition for citizens over baskets of taxes and services and (2) limiting state tax power to export tax burdens to non-residents or out-of-state companies, or policies that would excessively harm the free-flow of commerce in the national economy.[51]

The MFA would be in this vein. The goals behind the legislation are to (1) provide a mechanism for states to collect their sales tax on sales to their residents and (2) eliminate unjustifiable tax distinctions between similar items sold in the same state. The MFA bill draft partly addresses these goals but can be strengthened to achieve two more important goals: (3) define the limits of state tax authority so as to prevent uncertainty and harm to interstate commerce, and (4) simplify the tax system to such a degree that online sellers do not face excessive and inequitable compliance burdens.

The proposed Act consists of six sections, the first of which is the title:[52]

- Section 2 authorizes each state belonging to the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement to require sellers to collect and remit sales tax on remote sales beginning 180 days after enactment. Non-SSUTA members may also require sellers to collect and remit sales tax on remote sales if they enact legislation including each of the following:

- Specify the tax and products and services subject to it.

- Provide a single entity in the state responsible for all sales tax administration, return processing, and audits; a single audit of a remote seller for all sales tax jurisdictions in the state; and a single sales and use tax return to be filed with the state’s single entity. Local jurisdictions may not require remote sellers to submit returns or collect tax beyond that required by the single state entity.

- Provide a uniform sales and use tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. among the state and local taxing jurisdictions.

- Source remote sales according to the method provided (delivery location, then billing address, then seller address).

- Provide a database indicating taxability of products and services, including exemptions, rates, and boundaries. Free of charge software to calculate tax on each transaction shall be made available, along with certification procedures for software providers.

- Waive liability (including penalties and interest) for remote sellers and software providers who incorrectly collect, remit, or non-collect sales and use tax if they rely on information or software provided by the state.

- Provide 90 days’ notice of any sales tax rate changes and waive collection liability for 90 days if notice is not provided.

- Section 3 notes that the Act should not be construed to expand state authority over any tax except sales and use taxes, does not alter the nexus determination standard, does not limit seller’s authority to choose tax software, does not alter state powers to regulate or license businesses, and does not encourage states to impose new taxes. Additionally, the Act does not preempt states’ choice for intrastate sourcing rules nor alter the Mobile Telecommunications Sourcing Act.

- Section 4 defines the various terms, including the sourcing rule.

- Section 5 allows the Act to be severed if parts are held unconstitutional.

- Section 6 indicates that the Act does not preempt or limit state powers except as provided.

Section 2 also includes a “small seller” (or de minimis) exception, exempting sellers from the Act’s obligations if the seller has total remote sales in the United States of less than $1 million. This provision will likely be removed in future drafts of the legislation because, in Chairman Goodlatte’s words, “laws should be so simple and compliance so inexpensive and reliable as to render a small business exemption unnecessary.”[53]

The focus going forward will therefore likely be on solidifying the law’s simplification requirements rather than carving out certain small businesses. Areas of potential improvement include:

- Require 90 days’ notice of sales tax base changes, in addition to rate changes.[54]

- Ensure that states’ software and data are compatible with each other, with the goal of each vendor being able to use just one software program for all tax jurisdictions.

- Provide the option for states and sellers to use a blended tax rate for a state, rather than determining the combined state and local tax rates for each jurisdiction in a state.

- Limit state audit authority in states where a business does not have physical presence.

- Clarify that states cannot pursue remote seller sales tax collection except through the mechanisms provided.

- Give federal courts jurisdiction over MFA cases, to ensure sellers have a meaningful remedy if states fail to comply with the required simplifications.

What Is Destination-Sourcing, Origin-Sourcing, and Hybrid Origin-Sourcing?

To avoid double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. , sales tax requires a consistent, uniform rule about where sales occur, known as a sourcing rule. Unless states adhere to such a rule, a transaction involving a consumer in California, a warehouse in Texas, a website server in Nebraska, an incorporation in New Jersey, a corporate headquarters in New York, and trucks crossing many states could conceivably be taxed multiple times as each state jockeys for its asserted share. Every state with a sales tax uses destination-sourcing (the location of the sale is considered the location where the customer receives it) for interstate sales and all but two states also use destination-sourcing for intrastate sales. Only two states (Texas and Virginia) use origin-sourcing (the location of the sale is considered the seller’s place of business) for intrastate sales, and the trend has been to move from origin-sourcing to destination-sourcing.[55]

The Marketplace Fairness Act proposal codifies a default sourcing rule for Internet-based transactions based on destination:

- Delivery Location: “[T]he location to which a remote sale is sourced refers to the location where the item sold is received by the purchaser, based on the location indicated by instructions for delivery that the purchaser furnishes to the seller.”

- If Delivery Location Not Known, then Customer’s Address or Billing Address: “When no delivery location is specified, the remote sale is sourced to the customer’s address that is either known to the seller, or if not known, obtained by the seller during the consummation of the transaction, including the address of the customer’s payment instrument if no other address is available.”

- If Customer’s Address Not Known, Seller’s Address: “If an address is unknown and a billing address cannot be obtained, the remote sale is sourced to the address of the seller from which the remote sale was made.”

These sourcing rules conform to the notion that the sales tax is paid, legally and economically, by the consumer purchasing the item and the tax should therefore be based on where the consumer receives the item and lives. Only if this information is not known does the default switch to the seller’s location.

Hybrid origin-sourcing (HOS) has been raised as an alternative to current sales tax destination-sourcing rules in general and the MFA in particular. Under this approach, the sale would always be sourced as the taxing jurisdiction of the seller. Some mechanism would be established send the revenue to the taxing jurisdiction of the buyer. The tax would thus be collected and then redistributed.

For example, assume a Rhode Island (7 percent state sales tax) consumer purchases an item on the Internet from a seller located in Washington State (6.5 percent state sales tax plus local sales taxes averaging 2.38 percent). Under the current destination-sourcing rule, the sale is sourced to Rhode Island, and a 7 percent tax is due. Under an origin-sourcing system, the sale is sourced to Washington State and a tax of 6.5 percent plus the local sales tax is due. Under the HOS system, the sale is sourced to Washington State and a tax of 6.5 percent plus the local sales tax is due, but the money is remitted to Rhode Island.

The inspiration for the HOS approach is the International Fuel Tax Agreement (IFTA), where commercial motor vehicles buy fuel and pay fuel taxes as they go, but each quarter, the paid tax revenue is divided among the states on the basis of mileage traveled. Prior to IFTA, truckers had an incentive to purchase fuel in states with low fuel taxes even if most of their driving was in states with high fuel taxes. In many ways, IFTA switched commercial fuel taxes from origin-sourcing to destination-sourcing after the origin-sourcing system proved to encourage tax avoidance to the detriment of state infrastructure needs.

Why Is Hybrid Origin-Sourcing (HOS) Not a Viable Solution?

Any solution to the problem of uncollected sales and use taxes on remote sales must provide some mechanism for states to collect their sales tax on sales to their residents, eliminate unjustifiable tax distinctions between similar items sold in the same state, define the limits of state tax authority so as to prevent uncertainty and harm to interstate commerce, and simplify the tax system to such a degree that online sellers do not face excessive and inequitable compliance burdens.

Origin-sourcing would seek to address the problem by requiring sellers to know the tax laws and rates only in the places that they sell. While this is the HOS proposal’s primary advantage, there are many significant disadvantages.

HOS Origin Is Not Easily Defined and Enforced, Resulting in Likely Tax Arbitrage

Origin is not an easy-to-define location for Internet sales. It can potentially be the place where the company has most of its employees, its state of incorporation, its headquarters location, the place where the order was accepted, the place where the order was processed, the place from where the goods were shipped, or the location of a web server.

A uniform federal standard defining and enforcing origin would be essential to prevent states from subjecting companies to multiple taxation, such as from one state taxing based on where the sale was processed and another taxing based on where most employees work. Former Rep. Christopher Cox, advocating the HOS proposal to the House Judiciary Committee, embraced a “number of employees” standard but ambiguously added that additional language would be needed to “describe instances where the number of employees would not be an appropriate measure, and prescribe methods to use, as alternative means of designating Home Jurisdiction, either the state where most physical assets are located or the state designated as the principal place of business for federal income tax purposes.”[56]

With so much tax liability resting on where a business chooses to have its “origin,” Internet businesses would have enormous incentive to arbitrage their location decisions based on tax planning rather than good business practices. Creating a separate sales entity in a no-tax state, for instance, would easily manipulate the HOS origin definition. Highly mobile Internet businesses are more able to take advantage of zero or low-sales tax states more than traditional businesses, gaming the system and potentially causing a race to the bottom on Internet taxation.

HOS Problematically Transforms the Sales Tax into a Business Tax

The sales tax is presently a consumption tax legally and economically borne by consumers, and the HOS proposal would effectively transform it into a business tax, legally and economically borne by sellers. This structural remaking of the sales tax is an excessive solution merely to address the problem of Internet sales. Further, economists generally agree that consumption taxes are less harmful to economic growth and job creation and that business taxes are more harmful, with the U.S. relying less on consumption taxes and more on business taxes than our international competitors. Shifting even more of the tax burden from consumption to business, while also exempting imports and taxing exports as the HOS proposal does, would exacerbate that trend and be poor tax policy. HOS would tax based on production but then distribute based on consumption, a hybrid approach with no precedent that is likely to result in distortions in economic activity.

HOS’s Compact Structure Would Fail to Achieve Uniformity and Certainty

Uniformity and certainty on this issue can only be achieved by a federal structure of some kind.

While the HOS proposal would require federal legislation, it relies on states complying voluntarily through a compact structure. With some states adhering and others not adhering, it would undermine uniformity and taxpayer certainty. Prior attempts at voluntary interstate tax compacts (the Multistate Tax Compact and the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement) have failed to gain even a majority of states as members due to states resisting changes to their tax systems, and this proposed compact would face similar challenges.

HOS Leads to Taxation without Representation

Instead of consumers paying taxes to their state of residence where they live and vote, under HOS, purchases would be taxed by other states where the consumer may have little or no connection. For example, a California resident purchasing an item from a Pennsylvania seller would owe Pennsylvania sales tax based on Pennsylvania taxability rules. (The rules are not intuitive: Pennsylvania taxes soft drinks and exempts clothing; California does the reverse.) Pennsylvania would therefore expand the scope of its tax system to consumers all over the country, as would each state. A system where states are able to tax the residents of other states sets up worrisome taxation without representation problems. The California consumer has little power to choose representatives or influence Pennsylvania’s tax policy, but his or her purchases are subject to it. HOS perhaps ignores this problem by claiming that the businesses are the actual taxpayers, but the HOS proposal also has businesses collecting taxes for states where they have no physical presence.

HOS Retains Unjustifiable Tax Distinctions for Similar Items in the Same State

The HOS proposal does not eliminate unjustifiable tax distinctions between similar items sold in the same state. For example, residents in states without a sales tax (Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon) would pay sales tax on Internet purchases but not on brick-and-mortar purchases. A Rhode Island resident would pay a 7 percent tax on brick-and-mortar purchases, but higher or lower tax rates from other states for Internet purchases (with the revenue returned to Rhode Island). This not only preserves tax rate distinctions that have no economic rationale, but would likely also confuse consumers.

HOS Does Not Include Needed Tax Simplifications

Both MFA and the HOS proposal authorize state taxation of remote sellers, but the HOS proposal eliminates the requirement that states simplify their sales tax systems to make such compliance feasible for sellers. This would be an enormous missed opportunity to achieve significant improvements for all retailers (brick-and-mortar and Internet) who deal with our complex, burdensome state sales tax systems. Pure origin-sourcing sidesteps simplification by limiting seller liability to one jurisdiction (where the seller has physical location), but under the HOS proposal sellers must still comply with multiple jurisdictions because it requires taxes to be remitted to the customer’s taxing jurisdiction. The HOS proposal speaks of a quasi-governmental entity to facilitate the redistribution of revenues, but practical experience with sales tax collection strongly suggests that sellers will still bear a large part of the compliance burden. Sellers under HOS may thus face the same compliance obligations as they do under MFA, but with the simplification and uniformity improvements included in the MFA bill.

HOS Likely Violates the Due Process Clause of the U.S. Constitution

Laws involving state taxation must comply with both the Commerce Clause and the Due Process Clause of the U.S. Constitution. The Due Process Clause restricts state jurisdiction to tax a person if that person has no “minimum contacts” with a state. Past court cases have found “minimum contacts” where sellers have been physically present in the state, had a contract with an in-state resident, directed products to the state, sought to serve residents in the state, or even had a “non-passive” website accessible from the state.[57]

Generally, any tax law that satisfies the Commerce Clause will also satisfy the Due Process Clause because “substantial nexus” is a higher standard than “minimum contacts.” However, the HOS proposal would create tax liability for consumers and sellers in many states where they lack minimum contacts. A Rhode Island consumer would pay Washington State’s sales tax rate even if he has zero connection to Washington; in turn, Washington would exercise tax power over non-residents all over the country. This is problematic because states are constitutionally barred from asserting jurisdiction over persons if those persons lack the requisite minimum contacts with the state. The HOS proposal can only address this Due Process concern by recasting the business as the taxpayer rather than the consumer, but this would merely change the form of the relationship and not the economic reality. While Congress can modify threshold requirements for the Commerce Clause, they constitutionally cannot alter the threshold requirements for the Due Process Clause.

HOS May Exceed Congress’s Commerce Clause Power

Congress’s power over interstate commerce is extensive, but the courts have been skeptical of federal laws that coerce states into actions that are generally left to the states in our federalist system.[58] The HOS proposal potentially requires states to transform intrastate taxation of their own residents, by modifying sourcing rules, changing the liability of who owes sales tax, and forbidding the collection of use tax from in-state consumers. Also, the HOS scheme may only be viable if every state adopts the origin-based sourcing rule for all sales. Such federal direction of internal state tax policy would exceed the powers of the federal government as determined in recent Supreme Court rulings.

Conclusion

Our economy has changed and technological progress is amazing. But the best computer can’t make up for archaic state tax systems, just as computers haven’t reduced to zero the cost of complying with the federal income tax. No matter how much technology advances, the principle that states should have limited powers should remain timeless. The physical presence rule is a sensible rule: state services are based on physical presence and geographic lines, so state taxes ought to be as well. Consumers who live and work in a state should pay sales tax there when they buy things.

At the same time, the steadily increasing growth of Internet-based commerce has led to frustration with the physical presence standard as applied to Internet sellers, primarily due to disparate sales tax treatment of similar goods within states. This can be addressed while also ensuring that some standard exists to restrain states from engaging in destructive behaviors like tax exporting to non-voters or imposing heavy compliance costs on interstate businesses. Further, because economic integration is greater now than it has ever been before, the economic costs of nexus uncertainty are also greater today and can ripple through the economy much more quickly.

The approach taken by the MFA is the only one that can (1) provide some mechanism for states to collect their sales tax on sales to their residents, (2) eliminate unjustifiable tax distinctions between similar items sold in the same state, (3) define the limits of state tax authority so as to prevent uncertainty and harm to interstate commerce, and (4) simplify the tax system to such a degree that online sellers do not face excessive and inequitable compliance burdens. Missing key simplifications can be added more easily to the MFA bill than undertaking the arduous and problem-laden task of completely remaking the sales tax system based on hybrid origin-sourcing.

[1] See Joseph Henchman, Congress to Hear Testimony on Internet Sales Taxes, Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Mar. 11, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/house-chairman-goodlatte-releases-principles-taxing-internet-sales.

[2] Joseph Henchman & Richard Borean, State Sales Tax Jurisdictions Approach 10,000, Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Mar. 24 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/article/state-and-local-sales-tax-rates-2014.

[3] The three states with broad sales taxes that encompass most services are Hawaii, New Mexico, and South Dakota. In Hawaii and New Mexico, the tax is legally the obligation of the seller, not the consumer. Officials in those states are adamant that these features are so distinct from other sales taxes that they refer to them by unique names: the General Excise TaxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. in Hawaii and the Gross Receipts Tax in New Mexico.

[4] Not all local sales tax jurisdictions have a corresponding use tax. Professor John Mikesell, the nation’s leading sales tax expert, counted in 1992 that use tax would be owed in 4,452 of the then-6,000 local sales tax jurisdictions.

[5] About half the states also include a use tax payment line on their income tax form, but the collections from this method are minimal. Features of this sometimes include an exemption for purchases under a certain threshold and a lookup table where taxpayers can pay a certain amount based on their income rather than tracking all purchases throughout the year. See, e.g., Nina Manzi, Use Tax Collection on Income Tax Returns in Other States, Minnesota House of Representatives Research Department Policy Brief (Apr. 2012), http://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/hrd/pubs/usetax.pdf.

[6] See Henneford v. Silas Mason Co. Inc., 300 U.S. 577 (1937).

[7] See PricewaterhouseCoopers, Retail Sales Tax Compliance Costs: A National Estimate (Apr. 2006), http://netchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/cost-of-collection-study-sstp.pdf.

[8] U.S. Census Bureau, Quarterly Retail E-Commerce Sales 1st Quarter 2014 (May 15, 2014), http://www.census.gov/retail/mrts/www/data/pdf/ec_current.pdf.

[9] See H.B. 1515, 2013 Leg. (Md. 2013) (applying the sales tax to gasoline unless the state can require the collection of sales tax on sales by out-of-state sellers by December 1, 2015); Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 5741.03 (directing that revenue from remote seller tax collection be used to lower income tax rates); Va. Code Ann. § 58.1-2217 (reducing the wholesale gasoline tax from 6 percent to 5.1 percent if the federal government enacts legislation to compel remote sellers to collect state and local sales and use tax by 2015). See also Scott Walker, Letter of May 15, 2013, http://www.standwithmainstreet.com/getobject.aspx?file=Letter%20from_Governor_Scott_Walker (pledging to use any remote seller tax collection revenue to reduce income tax rates).

[10] See Donald Bruce, William F. Fox, & LeAnn Luna, State and Local Government Sales Tax Revenue Losses from Electronic Commerce (Apr. 13, 2009), http://cber.utk.edu/ecomm/ecom0409.pdf.

[11] See Korey Clark, Online Sales Tax Push Continues Despite Disappointing Returns, State Net, Mar. 8, 2013, http://www.lexisnexis.com/legalnewsroom/corporate/b/business/archive/2013/03/08/online-sales-tax-push-continues-despite-disappointing-returns.aspx.

[12] See id.

[13] Empiris LLC, Jeffrey A. Eisenach & Robert E. Litan, Uncollected Sales Taxes on Electronic Commerce: A Reality Check (2013), http://netchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/eisenach-litan-state-estimates.pdf.

[14] See Joseph Henchman, Internet Sales Tax Collections Falling Far Short of Experts’ Estimates, Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Mar. 18, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/internet-sales-tax-collections-falling-far-short-experts-estimates.

[15] See, e.g., The Federalist No. 42 (James Madison, 1787) (“To those who do not view the question through the medium of passion or of interest, the desire of the commercial States to collect, in any form, an indirect revenue from their uncommercial neighbors, must appear not less impolitic than it is unfair; since it would stimulate the injured party, by resentment as well as interest, to resort to less convenient channels for their foreign trade. But the mild voice of reason, pleading the cause of an enlarged and permanent interest, is but too often drowned, before public bodies as well as individuals, by the clamors of an impatient avidity for immediate and immoderate gain.”); Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1, 224 (1824) (Johnson, J., concurring) (“[G]uided by inexperience and jealousy, began to show itself in iniquitous laws and impolitic measures, from which grew up a conflict of commercial regulations, destructive to the harmony of the States, and fatal to their commercial interests abroad. This was the immediate cause that led to the forming of a convention.”); 1 Story Const. § 497 (“If there is wisdom and sound policy in restraining the United States from exercising the power of taxation unequally in the states, there is, at least, equal wisdom and policy in restraining the states themselves from the exercise of the same power injuriously to the interests of each other. A petty warfare of regulation is thus prevented, which would rouse resentments, and create dissensions, to the ruin of the harmony and amity of the states.”).

[16] See U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 3 (Interstate Commerce Clause); U.S. Const. art. I, § 10, cl. 2 (Import-Export Clause); U.S. Const. art. I, § 10, cl. 3 (Tonnage Clause); U.S. Const. art. IV, § 2, cl. 1 (Privileges and Immunities Clause); U.S. Const. amend. XIV, § 1 (Privileges or Immunities Clause).

[17] See, e.g., Freeman v. Hewit, 329 U.S. 249, 252-53 (1946) (“A State is . . . precluded from taking any action which may fairly be deemed to have the effect of impeding the free flow of trade between States”); Leloup v. Port of Mobile, 127 U.S. 640, 648 (1888) (“No State has the right to lay a tax on interstate commerce in any form.”).

[18] See, e.g., Western Live Stock v. New Mexico, 303 U.S. 250, 254 (1938) (holding that states can impose a “just share of the state tax burden” on those in the state engaged in interstate commerce); Spector Motor Service v. O’Connor, 340 U.S. 602 (1951) (invalidating state taxes on those exclusively engaged in interstate commerce); Railway Express Agency v. Virginia (I), 347 U.S. 359 (1954) (invalidating an annual license tax imposed on the in-state gross receipts of an out-of-state company); Railway Express Agency v. Virginia (II), 358 U.S. 434 (1959) (upholding an identical tax structured as a franchise tax on in-state going concern value, measured by in-state gross receipts).

[19] See Complete Auto Transit, Inc. v. Brady, 430 U.S. 274, 285 (1977).

[20] For a discussion of the case history of the other elements of the Complete Auto test, see Joseph Henchman, State Taxation of Interstate Commerce: A Primer, Tax Foundation Background Paper (forthcoming 2014).

[21] See National Bellas Hess v. Dep’t of Revenue of State of Ill., 386 U.S. 753 (1967).

[22] Id. at 759-60.

[23] See, e.g., Harvey S. Rosen, Public Finance 467 (7th ed. 2005).

[24] See National Geographic v. California Board of Equalization, 430 U.S. 551, 559 (1977).

[25] See Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298 (1992).

[26] The Interstate Commerce Clause, by its own terms, is a grant of power to Congress to make laws to regulate commerce among the several states. The power of federal courts to act when Congress is silent was inferred as an implication of the commerce clause (the dormant, or negative, commerce clause). See, e.g., Willson v. The Black Bird Creek Marsh Co., 27 U.S. 245 (1829).

[27] N.Y. Tax Law § 1101(b)(8)(vi)

[28] See Overstock.com, Inc. v. New York State Dep’t of Taxation and Finance, 987 N.E.2d 621, 627 (N.Y. 2013) (“[I]t is not unreasonable to presume that affiliated website owners residing in New York State will reach out to their New York friends, relatives, and other local individuals in order to accomplish this purpose.”)

[29] See id. at 626-27 (“[N]o one disputes that a substantial nexus would be lacking if New York residents were merely engaged to post passive advertisements on their websites.”).

[30] See id. (“[T]he agency charged with enforcing the statute has expressly acknowledged that mere advertising is beyond the scope of the provision.”); id. at 629 (Smith, J., dissenting) (“Read literally, the statute would reach essentially all Internet advertising that links to a seller’s website: it includes any agreement for referral of customers, by a link or otherwise, ‘for a commission or other consideration.’ Since this literal reading would unquestionably render the statute unconstitutional, the Department of Taxation and Finance has adopted a narrowing construction, largely ignoring the words “or other consideration,” and applying the presumption only where the website receives a commission or similar compensation . . . .”).

[31] See, id. at 626 (“Active in-state solicitation that produces a significant amount of revenue qualifies as more than a ‘slightest presence’ . . . .”). The New York courts stated that the state need not prove that solicitation happened, but can just assume it did and consequently find nexus, unless the retailer proves it didn’t. See id. at 627 (“[I]t is not unreasonable to presume that affiliated website owners residing in New York State will reach out to their New York friends, relatives, and other local individuals in order to accomplish this purpose.”).

[32] See N.C. Gen. Stat. § 105.164.8(b)(3).

[33] See R.I. Gen. Laws § 44-18-15(a)(2).

[34] See Ark. Code Ann. § 26-52-117(d)-(e).

[35] See Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 32, § 9783(b)-(c).

[36] See Cal. Rev. & Tax Code § 6203(b)(5).

[37] See Ga. Code Ann. § 48-8-2(8)(M).

[38] See Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 36, § 1754-B(1-A)(C).

[39] See Minn. Stat. § 297A.66(4a).

[40] Missouri erroneously appears on some recent lists due to legislation passed but subsequently vetoed by their governor. See 2013 Mo. H.B. 253. Utah and West Virginia also erroneously appear on some lists due to statutes entitled “affiliate nexus” but that are unrelated to the one discussed here.

[41] See Conn. Gen. Stat. § 12-407(a)(12)(L).

[42] See 35 Ill. Comp. Stat. 105/2 & 110/2.

[43] See Performance Marketing Ass’n, Inc. v. Homan, 2012 WL 1986181 (Ill. Cir. Ct. May 11, 2012).

[44] See Tex. Tax Code Ann. § 151.107(a)(3) & Tex. Tax Code Ann. § 151.107(a)(8).

[45] See GrantThornton LLP, Texas Enacts Major Legislation that Includes Sales Tax Affiliate Nexus Provisions at 2 (Aug. 9, 2011), http://goo.gl/nIuIuF.

[46] See Colo. Rev. Stat. § 39-21-112(3.5). Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Vermont have also enacted “warning law” statutes but only with the requirement that taxpayers be notified at the time of purchase that they may owe use tax. See Okla. Stat. § 710:65-21-8; S.D. Codified Laws § 10-63-2; Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 32, § 9783(b)-(c). North Carolina adopted a regulatory ruling imposing requirements similar to the Colorado law; the ruling was subsequently invalidated by a federal judge and abandoned by the department. See Tiffany Kaiser, Amazon Privacy Lawsuit Settled Between NC Department of Revenue, ACLU, Daily Tech, Feb. 9, 2011, http://goo.gl/vIUXNe.

[47] See Direct Mktg. Ass’n v. Huber, No. 10-CV-01546-REB-CBS, 2012 WL 1079175, at *6 (D. Colo. Mar. 30, 2012) (enjoining the statute on First Amendment grounds), rev’d sub nom. Direct Mktg. Ass’n v. Brohl, 735 F.3d 904, 2013 WL 4419324, at *14-15 (10th Cir. Aug. 20, 2013), cert. granted (U.S. Jul. 1, 2014) (No. 13-1032) (finding the Tax Injunction Act denies federal court jurisdiction over the notice statute). See also Joseph Henchman, Colorado’s Amazon Tax: It’s an Amazon Tax, Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Mar. 10, 2010, http://goo.gl/jsVsGV (“The compliance burden has been contrived to be so burdensome that it’s not much different from a sales tax compliance obligation.”).

[48] See Amazon.com LLC v. Lay, 758 F.Supp.2d 1154 (W.D. Wash. 2010). See also Arushi Sharma, ACLU Joins Fight against the North Carolina “Amazon Tax” Disclosure Demands, Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Jun. 24, 2010, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/aclu-joins-fight-against-north-carolina-amazon-tax-disclosure-demands.

[49] Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

[50] See generally George Isaacson, A Promise Unfulfilled: How the Streamlined Sales Tax Project Failed to Meet Its Own Goals for Simplification of State Sales and Use Taxes, 30 State Tax Notes 339 (Oct. 27, 2003); Joseph Henchman, Nearly 8,000 Sales Taxes and 2 Fur Taxes: Reasons Why the Streamlined Sales Tax Project Shouldn’t Be Quick to Declare Victory, Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Jul. 28, 2008, https://taxfoundation.org/article/testimony-maryland-legislature-streamlined-sales-tax-project. See also Billy Hamilton, Happy Birthday, SSUTA!, 66 State Tax Notes 513 (Nov. 12, 2012); John Buhl, Governing Board Gives Initial Approval to Clothing Threshold, 50 State Tax Notes 687 (Dec. 15, 2008); Eric Parker, New Jersey Fur Tax Sparks Streamlined Governing Board Meeting Dispute, 42 State Tax Notes 853 (Dec. 25, 2006).

[51] See, e.g., 4 U.S.C. § 111 (preempting discriminatory state taxation of federal employees); 4 U.S.C. § 113 (preempting state taxation of nonresident members of Congress); 4 U.S.C. § 114 (preempting discriminatory state taxation of nonresident pensions); 7 U.S.C. § 2013 (preempting state taxation of food stamps); 12 U.S.C. § 531 (preempting state taxation of Federal Reserve banks, other than real estate taxes); 15 U.S.C. § 381 et seq. (preempting state and local income taxes on a business if the business’s in-state activity is limited to soliciting sales of tangible personal property, with orders accepted outside the state and goods shipped into the state (often referred to as Public L. 86-272)); 15 U.S.C. § 391 (preempting discriminatory state taxes on electricity generation or transmission); 31 U.S.C. § 3124 (preempting state taxation of federal debt obligations); 43 U.S.C. § 1333 (2)(A) (preempting state taxation of the outer continental shelf); 45 U.S.C. § 101 (preempting state income taxation of nonresident water carrier employees); 45 U.S.C. § 501 (preempting state income taxation of nonresident employees of interstate railroads and motor carriers, and Amtrak ticket sales); 45 U.S.C. § 801 et seq. (preempting discriminatory state taxation of interstate railroads); 47 U.S.C. § 151 (preempting state taxation of Internet access, aside from grandfathered taxes); 47 U.S.C. § 152 (preempting local but not state taxation of satellite telecommunications services); 49 U.S.C. § 101 (preempting state taxation of interstate bus and motor carrier transportation tickets); 49 U.S.C. § 1513 et seq. (preempting state taxation of interstate air carriers and air transportation tickets); 49 U.S.C. § 40101 (preempting state income taxation of nonresident airline employees); 49 U.S.C. § 40116(b) (preempting state taxation of air passengers); 49 U.S.C. § 40116(c) (preempting state taxation of flights unless they take off or land in the state); 50 U.S.C. § 574 (preempting state taxation of nonresident members of the military stationed temporarily in the state).

[52] S. 336 / S. 743 / H.R. 684, 113th Cong. (2013-2014).

[53] See Joseph Henchman, House Chairman Goodlatte Releases Principles for Taxing Internet Sales, Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Sep. 20, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/house-chairman-goodlatte-releases-principles-taxing-internet-sales.

[54] A prior version of this list of suggestions included giving remote sellers notice for sales tax holidays (which exist in 17 states) and waiving liability if notice was not provided. It is no longer included because the 90-day notice requirement and liability waiver for base changes, if included, would encompass sales tax holidays.

[55] States that have transitioned from origin-sourcing at some level to full destination-sourcing in the last decade include Kansas, Ohio, Tennessee, and Utah.

[56] Exploring Alternative Solutions on the Internet Sales Tax Issue: Hearing on H.R. 684 before the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 113th Cong. 22 (Mar. 12, 2014) (statement of Christopher Cox), http://judiciary.house.gov/_cache/files/a034c54e-46a6-4570-9e86-f41160dee495/cox-testimony.pdf.

[57] For a detailed discussion of personal jurisdiction standards in the context of interstate taxation, see Joseph Henchman, Why the Quill Physical Presence Rule Shouldn’t Go the Way of Personal Jurisdiction, 46 State Tax Notes 387 (Nov. 5, 2007), https://taxfoundation.org/article/why-quill-physical-presence-rule-shouldnt-go-way-personal-jurisdiction.

[58] See, e.g., Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Management District, 568 U.S. ____ (2013), 133 S. Ct. 2586 (Jun. 25, 2013) (holding that Congress may not condition benefits on the relinquishment of constitutional protections); Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898, 935 (1997) (“The Federal Government may neither issue directives requiring the States to address particular problems, nor command the States’ officers, or those of their political subdivisions, to administer or enforce a federal regulatory program. It matters not whether policymaking is involved, and no case by case weighing of the burdens or benefits is necessary; such commands are fundamentally incompatible with our constitutional system of dual sovereignty.”); New York v. United States, 505 U.S. 144, 188 (1992) (“The Constitution enables the Federal Government to pre-empt state regulation contrary to federal interests, and it permits the Federal Government to hold out incentives to the States as a means of encouraging them to adopt suggested regulatory schemes. It does not, however, authorize Congress simply to direct the States . . . .”).