Key Findings

- Personal saving and investment are necessary for long-term economic growth.

- The income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. treats ordinary saving more harshly than income used for consumption.

- The tax code treats a limited amount of personal saving, namely that done through retirement savings vehicles, in a neutral way relative to consumption.

- Retirement plans provide an important source of retirement income for the middle class; more than half of taxable private-sector retirement income flows to households with AGI under $100,000.

- The complex structure of retirement savings plans and the rules and restrictions applied to these savings vehicles limit their effectiveness in reducing the tax bias against saving and create an incentive for immediate consumption.

- Long-term savings are in decline, and half of Americans are at risk for not saving enough to maintain their current standard of living in retirement.

- Changes to tax laws governing long-term savings could remove the excess tax burden on saving and investment, helping individuals to better provide for their financial future.

Introduction

Personal saving, the setting aside of resources today to get benefits in the future, is taxed in a variety of ways in the United States. Ordinary income tax treatment taxes income when first earned, and, if saved, taxes the returns on the saving (the reward one “buys” by saving). By contrast, income used for immediate consumption is taxed only once by the income tax; the income tax does not fall again on what one buys with the after-tax income. This second layer of tax on the rewards for saving favors immediate consumption over delayed consumption.

The tax treatment of retirement accounts, however, removes this bias for a limited amount of personal saving. Neutrality is achieved in one of two ways: defer tax on the saving and tax all returns of principal and earnings, or tax the amount saved up front and exempt all returns from additional tax. Either way, saving in retirement systems and consumption face the same lifetime tax burden, in present value. This neutrality is limited, though, by numerous rules and restrictions that govern retirement accounts, making the tax structure of long-term savings complex and biased.

Congress should consider reforms to the complicated structure of long-term saving vehicles. Discriminatory taxes on capital income discourage saving and slow capital formation, lowering the growth of employment, wages, and GDP. Removing contribution and age limitations and eliminating withdrawal penalties for tax-neutral savings accounts would make the tax code more conducive to personal saving and would improve long-term growth.

The Four Ways the Tax Code Applies to Savings

Personal saving is the purchase of an income-earning asset, setting aside a lump sum of resources today to get a stream of benefits in the future. The way this process interacts with the tax code can often be quite complex, but we can think about it this way: how the principal, or the initial resources one invests, is taxed and how the returns, or the benefits one accrues, are taxed.

| Tax on Principal | No Tax on Principal | |

|---|---|---|

|

Tax on Returns |

|

|

|

No Tax on Returns |

|

|

This table illustrates the four ways that the federal tax code applies to saving and investment. The columns show how the principal is taxed; if one pays tax on the resources invested, such as paying income taxes on the money used to purchase a home, that creates a layer of tax. The rows illustrate how the returns are taxed; if one pay taxes on the returns to investment, such as capital gains taxes, that too creates a layer of tax.

Under a saving/consumption-neutral tax system, each dollar, whether it is consumed immediately or saved for future consumption, is taxed only once, as in the case in the lower-left and upper-right quadrants of Table 1. Neutrality is violated when multiple layers of tax apply to the same dollar, as in the upper-left quadrant. This distorts the choice between immediate consumption and saving, skewing it towards immediate consumption because the multiple layers reduce after-tax return to saving. Some income escapes tax entirely, as in the lower right quadrant.

Multiple layers of taxation lead to bias against saving. In addition to personal income taxes on the principal and the return, corporate income taxes on business profits and estate and gift taxes mean that saving, in some instances, can face up to four layers of taxation.[1] These layers of taxes discourage saving and investment.

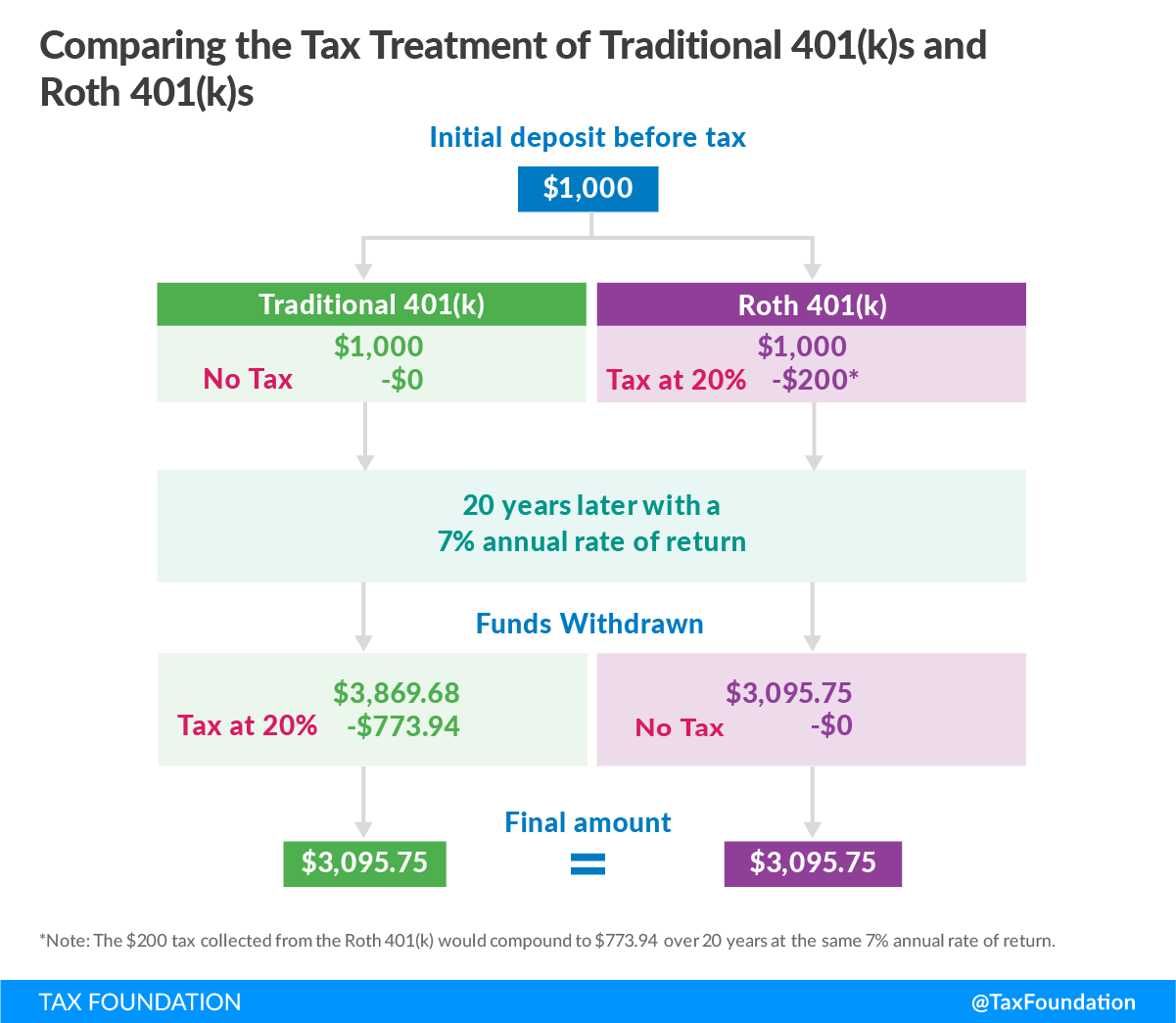

In traditional-style, or tax-deferred, accounts, the initial savings are not subject to income tax and the returns are subject to tax when they are withdrawn and consumed. In Roth-style accounts, the initial savings are subject to income tax and the account grows tax-free.

If retirement savers were subject to a constant tax rate over time, these two tax treatments would be identical.[2] For example, assuming a 20 percent tax rate, an initial $1,000 of pretax income could become $1,000 of principal saved in a traditional 401(k), or, after paying tax, a deposit of $800 in a Roth 401(k). After allowing the investments to mature over 20 years at a bit over 7 percent annual rate of return,[3] the traditional 401(k) would grow to $4,000 while the Roth 401(k) would grow to $3,200. However, upon withdrawal, the traditional 401(k) would be taxed 20 percent, or $800, and drop in value to the same $3,200 as the Roth 401(k).

Figure 1.

If savers anticipate being in the same tax bracket before and after retirement, they should be indifferent between the two types of accounts because both result in the same after-tax incomeAfter-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. . From the government finance perspective, though, the structure of traditional retirement accounts is preferable. The government has a lower discount rate than private investors, so by allowing the assets in retirement accounts to mature in the private market before taxing them, the government earns more revenue than it would under Roth-style tax treatment.[4] This is especially true if savers are lucky enough to invest in an asset that yields unusually high returns (called “supernormal” returns). Having the government share in these gains in a saving-deferred account does not discourage initial saving.

Retirement Accounts are Significant Source of Capital Income for the Middle Class

Retirement saving plans constitute a large portion of the saving for the middle class, and provide a large share of the capital income earned by the middle class. It is generally difficult to track the level of capital income in retirement accounts, especially because it does not show up on Internal Revenue Service (IRS) forms until it is distributed.[5] The information gleaned from IRS forms, though, reveals that retirement distributions are a significant source of income for the middle class.

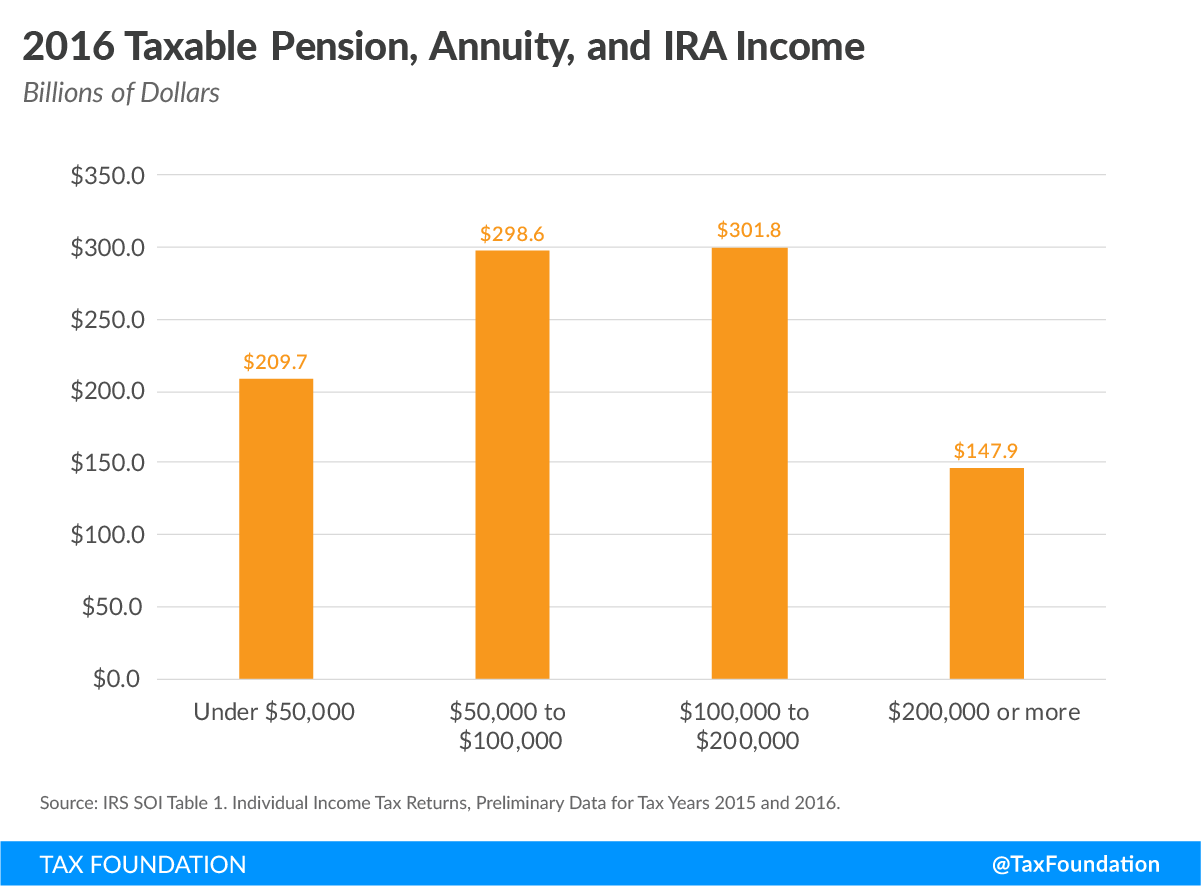

Figure 2.

Figure 1 shows income derived from taxable pensions and personal retirement saving vehicles, but not Social Security, by income bracket. More than half of this retirement income ($508 billion out of $958 billion) goes to retirees making less than $100,000 a year. Nearly 85 percent of this retirement income ($810 billion of the $958 billion) goes to households that make under $200,000. The middle class largely invests through retirement saving vehicles, earning capital income where it will receive favorable tax treatment.

Measuring capital income only when it is distributed does not tell the entire story. First, counting distributions when made includes earnings from earlier years that were not reported as accrued. Second, mandated withdrawals from previously-deferred accounts tells us nothing about what those accounts are currently earning. An IRA might lose money in a stock market dip, but that year’s withdrawal would be recorded as income in the income distribution and tax distribution tables. These shortcomings in measuring capital income in retirement accounts create an inaccurate picture of who has capital income.[6]

Counting capital income as it accrues, rather than waiting until it is distributed, more accurately shows who has this type of income. Between 1989 and 2007, asset holdings in both taxable and nontaxable accounts increased at a faster pace for lower-income individuals than it did for higher-income individuals, with the increase occurring disproportionally in tax-neutral accounts.[7] Measuring yearly accrued capital gains confirms that retirement accounts are how the middle class earns capital income. Remember, though, that looking at these accruing gains to learn who is receiving the benefits of saving and investment does not mean that it is right to tax the gains as they accrue. Doing that would create a tax bias against the saving.

Proper Treatment of Retirement Accounts is Limited

While retirement savings vehicles are not subject to the undue burden of double taxation, they face myriad restrictions. These complexities limit the availability of neutral treatment to a certain amount of dollars saved, and create a confusing multiplicity of separate types of accounts eligible for proper tax treatment.

The IRS website lists 15 general types of retirement plans.[8] Many of these categories also have subcategories, and each has its own sets of rules, including contribution limits, tax deduction limits, and guidelines for when savers can or must withdraw their money.

Some of the most common restrictions are limits on contributions and benefits, which differ depending on the type of the plan. For tax year 2018, for example, total contributions to all traditional and Roth IRAs cannot be more than $5,500. This leaves no marginal incentive to save beyond the contribution limits.

|

Source: Internal Revenue Service, “Site Index – Information for Retirement Plans” |

|||

| Roth IRA | Traditional IRA | 401(k) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contribution Limits | Total contributions to all your traditional and Roth IRAs cannot be more than $5,500 (or $6,500 if you are age 50 or older) | Total contributions to all your traditional and Roth IRAs cannot be more than $5,500 (or $6,500 if you are age 50 or older) | $18,500 for employee-elected deferrals Total annual contributions cannot exceed the lesser of 100% of the participant’s compensation or $55,000 |

| Income Limit | For married couples filing jointly, the income phaseout range is $189,000 to $199,000 | For married couples filing jointly, where the spouse making the IRA contributions is covered by a retirement plan at work, the income phaseout range is $101,000 to $121,000 | No more than $275,000 of an employee’s compensation can be taken into account when figuring contributions |

| Required Minimum Distribution Age | Roth IRAs do not require withdrawals until after the death of the owner | April 1 of the year following the calendar year in which you reach age 70½ | April 1 of the year following the calendar year in which you reach age 70½ or retire |

| Age Limit for Contributing | Can contribute to Roth IRAs regardless of age | Cannot make regular contributions to a traditional IRA in the year you reach 70½ and older | No upper age limitations |

Congress has imposed rules concerning the age at which retirement savers can or must make withdrawals. Distributions taken before normal retirement age, which can differ by plan, can result in an additional income tax of 10 percent on the amount withdrawn.[9] On the other hand, if savers wait too long to take distributions, generally past age 70½, they may have to pay a 50 percent excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. on the amount not distributed as required.[10] Though “early” distributions made for certain purposes from certain accounts may not be subject to extra taxes, the exceptions are narrow. Under these restrictions, savers often cannot use their savings as they see fit without incurring tax penalties. These threatened fines make it risky for lower-income people, who may not be able to save for emergencies and retirement in separate baskets, to use these accounts.

Rather than having a straightforward way to save for retirement, individuals must navigate this complex swath of disorganized restrictions and limitations. And, if individuals want to save more than the IRS allows, or save for other purposes, they generally must use tax-disadvantaged options to do so.

Restrictions, Rules, and Multiple Layers of Taxes Discourage Savings

Subjecting savings above certain limits or outside of favored accounts to double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. makes immediate consumption more attractive than saving for future consumption. This biased tax treatment, which reduces the after-tax return to savings, is one of the contributing factors to the broad decline in savings in the United States.[11] Undersaving has consequences for both personal financial security as well as the health of the national economy.

The National Retirement Risk Index evaluates how many households will be able to maintain their standard of living during retirement based on their level of savings. The most recent data, for calendar year 2016, show that 50 percent of American households are at risk of not having enough retirement income to maintain their preretirement standard of living.[12] The analysis concludes by saying that many of today’s workers will need to save more or work longer if they are to achieve a secure retirement.

Savings help provide a secure retirement because of the return on investment generated. Through the investment process, the benefits of individual savings are shared more broadly, as new investment leads to higher productivity, increased wages, and more goods produced for consumers to buy. People benefit when young from the higher wages, and benefit in retirement from the wealth that enables future consumption. If saving is reduced, by biased tax treatment, for example, it is likely to reduce the U.S. capital stock and reduce long-run levels of output and wages.[13]

Expanding No Tax on Principal, Tax on Return Treatment

Saving is beneficial for individuals and for the rest of the economy, and the tax code should not stand in the way of how much, or for what purposes, people save. Ideally, the double taxation of all saving and investment should be eliminated. Short of that, the structure of the long-term saving arrangements in the tax system should be reformed. Unfortunately, much of the recent congressional discourse on retirement saving has been in the direction of increasing the tax code’s burden on these accounts.

At least once, Congress has considered “Rothification,” or compulsory conversion, of retirement accounts.[14] This policy would convert some or all traditional defined-contribution plans to Roth-like plans, for future contributions, and has been primarily considered for its short-term revenue-generating potential. However, the ability of Rothification to raise long-term streams of revenue is highly suspect.[15] The money that is stored in tax-deferred accounts is not money that will go untaxed forever, so Rothification primarily changes the timing of tax revenue rather than the amount. It also is likely to lead to less revenue than traditional, tax-deferred treatment by not allowing retirement accounts to grow in the private market before facing tax, and depriving the government from participating in unusually high returns.

In considering policy actions like Rothification, Congress ignores the need to remove the tax burden on long-term saving, primarily viewing retirement saving as a source of potential short-term revenue. Compulsory conversion of retirement accounts does not diminish tax bias against saving.

A good example of how to move toward neutral taxation of saving can be found in Canada. In 2009, Canada implemented Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSA). These accounts are available to any residents 18 and older, may be used for any purpose, and can be easily opened at banks or online with investment choices determined by the account holder.[16] TFSAs receive Roth-style tax treatment; the contributions are not tax-deductible, but the earnings are tax-free. Additionally, withdrawals can be made at any time for any purpose without penalty. Contributions are limited, however, to CAD $5,500 a year (indexed to inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. ), but portions of the limit not used can be carried forward.[17]

Canada’s TFSAs would be a good model for America to build on. In tax year 2015, more than half of TFSAs were held by individuals making less than CAD $50,000 (approximately $38,000), showing that lower- to middle-income earners are willing and eager to utilize accounts that offer simplified, neutral treatment of saving, and that many of the benefits flow to people in those income categories.[18]

The United States could similarly move in this direction, though traditional, tax-deferred treatment would be ideal. Consolidating the myriad accounts currently available into a universal savings account would significantly simplify the structure of long-term saving arrangements and improve ease of access, especially for those who do not have retirement account options through their employer. Eliminating contribution limits would restore the marginal incentive to save that is currently lacking for individuals already making maximum contributions, while eliminating withdrawal penalties would let individuals save for whatever purpose they wish without fear of penalties if withdrawals must be made in emergencies.

Saving/consumption-neutral tax treatment should be available to everyone, regardless of income level, and usable for any purpose.

Conclusion

Personal saving serves a crucial economic function: it helps fund productive investments that drive economic growth, and it generates returns on those investments that allow individuals to build wealth and finance future consumption. The tax code treats a limited amount of personal saving, that which is done through retirement accounts, in a neutral way. But, if individuals want to save more than the limits or for other purposes, they face penalties that discriminate against saving in favor of consumption.

Instead of penalizing saving done outside of retirement accounts, neutral tax treatment should be expanded to all types of saving in any amount that individuals choose. Expanded neutrality would remove the disincentives to save that double taxation and complex rules create and help lift long-term economic growth.

Due in part to the disincentives created by biased tax treatment, long-term saving has long been in decline. Rather than considering changes to retirement saving for their revenue potential, Congress should seriously consider ways to remove the tax penalties on long-term saving by lifting or eliminating restrictions and reforming the structure of the various types of savings vehicles in the tax code.

[1] Andrew Lundeen, “Let’s Eliminate the Tax Code’s Bias Against Saving with Universal Savings Accounts,” Tax Foundation, May 11, 2015. https://taxfoundation.org/let-s-eliminate-tax-codes-bias-against-saving-universal-savings-accounts/

[2] Amir El-Sibaie, “What Rothification Means for Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, September 12, 2017. https://taxfoundation.org/what-rothification-means-for-tax-reform/

[3] 7.178 percent, to be exact, just to keep the example in round numbers!

[4] El-Sibaie, “What Rothification Means for Tax Reform.”

[5] Alan Cole, “Sources of Personal Income 2013 Update,” Tax Foundation, December 3, 2015. https://taxfoundation.org/sources-personal-income-2013-update

[6] Alan Cole, “Income Data is a Poor Measure of Inequality,” Tax Foundation, August 13, 2014. https://taxfoundation.org/income-data-poor-measure-inequality/#_ftnref18

[7] Philip Armour, Richard V. Burkhauser, and Jeff Larimore, “Deconstructing Income and Income Inequality Measures: A Crosswalk from Market Income to Comprehensive Income,” The American Economic Review 103(3), May 2013, 16-17.

[8] Internal Revenue Service, “Types of Retirement Plans.” https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-sponsor/types-of-retirement-plans. This list does not include other tax-qualified savings accounts that are used for nonretirement purposes such as 529 plans or Coverdell education savings accounts.

[9] IRS, “Hardships, Early Withdrawals and Loans.” https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/hardships-early-withdrawals-and-loans

[10] IRS, “Retirement Topics – Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs).” https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-required-minimum-distributions-rmds

[11] Alan Cole, “Losing the Future: The Decline of U.S. Saving and Investment,” Tax Foundation, October 1, 2014. https://taxfoundation.org/losing-future-decline-us-saving-and-investment

[12] Alicia H. Munnell, Wenliang Hou, and Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher, “National Retirement Risk Index Shows Modest Improvement in 2016,” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, January 2018. http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/IB_18-1.pdf

[13] Alan D. Viard, “ Capital Income Taxation: Reframing the Debate,” American Enterprise Institute, July 2013, 2. http://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/-capital-income-taxation-reframing-the-debate_172019152543.pdf

[14] H.R.1 Tax Reform Act of 2014, 113th Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/1/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22camp+discussion+draft%22%5D%7D#toc-H8A01B10FAA694FE3B6F586C20CFE5A07

[15] El-Sibaie, “What Rothification Means for Tax Reform.”

[16] Government of Canada, “The Tax-Free Savings Account.” https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/individuals/topics/tax-free-savings-account.html

[17] Government of Canada, “Contributions.” https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/individuals/topics/tax-free-savings-account/contributions.html#tfscntbtnrm

[18] Government of Canada, “Table 1C: TFSA holders by total income class,” https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/cra-arc/migration/cra-arc/gncy/stts/tfsa-celi/2015/tbl01c-eng.pdf.

Share this article