Key Findings

- State and local governments have used car rental excise taxes to raise revenue, including for projects like stadium construction and amateur sports funding. Forty-four states levy rental car excise taxes. Most states also permit county and municipal governments to add a rental car taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. , which may range from a flat-dollar surcharge to an ad valorem percentage of the value of the car rental.

- Car rental excise taxes are levied in concert with state and local sales taxes, airport concession fees, and vehicle license and registration recovery fees. This has created a byzantine structure of taxes and fees, with effective tax rates on consumers often exceeding 30 percent.

- Excise taxes on car rentals are unsound tax policy, as they narrowly target one industry in the hope of exporting the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. onto nonresidents. This has negative effects for residents when they pay higher prices for rental car services. States also experience lower economic growth when travelers adjust their behavior to avoid the tax. Evidence shows that travelers reduce their demand for car rentals when taxes rise and travel across state lines in search of a better deal.

- The sharing economy has given people the opportunity to rent out their own cars through peer-to-peer car-sharing arrangements. Peer-to-peer car sharing is projected to grow from $5 billion in 2016 to $11 billion in 2024—20 percent growth per year. This has led to discussions about whether to levy car rental excise taxes on car sharing. Instead of extending poor tax policy onto new business models, policymakers should reevaluate the tax regime imposed on car rental services. States that have not incorporated car rental services into their sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. bases should do so, and states with rental car excise taxes should repeal them.

Introduction

Travel and tourism are an important source of economic growth and tax revenue for state and local governments. Representing 2.7 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, the travel and tourism industry employed 5.4 million people in 2016.[1] Individuals travel for both work and leisure. Approximately 70 percent of travel expenditures are for leisure purposes, with the remaining 30 percent representing business travel.[2] Most travel and tourism comes from domestic trips: there were 2.2 billion domestic U.S. visits in 2017, compared to 76 million visits from people abroad.[3]

The economic importance of travel and tourism to the American economy has led state and local governments to consider how the tax code should treat nonresidents. Renting a car is an important aspect of American travel, giving visitors the flexibility they need to get to their destinations. State and local governments have used this as a revenue opportunity, creating a byzantine tax regime that targets rental car users and, by proxy, travelers from outside the taxing jurisdiction.

The rise of the sharing economy has impacted car rentals as it did other industries, including those driving taxicabs and providing short-term accommodations. Peer-to-peer car-sharing firms allow people who otherwise would not have the opportunity to rent their cars to participate in the car rental market. Like the case of ridesharing, incumbents argue that new economy firms are not on a level playing field and that the existing tax regime should equally apply to car-sharing businesses.

This paper provides an overview and assessment of rental car excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. es, their negative economic effects, and how policymakers should reform how car rental taxes work. It will also explore how policymakers should treat new economy firms providing a platform for car sharing, as many states are beginning to explore ways to incorporate car sharing into their tax codes. This paper will argue that excise taxes on car rentals should be repealed and the broader tax regime reformed to conform to the principles of sound tax policy.

History and Overview of Car Rental Excise Taxes

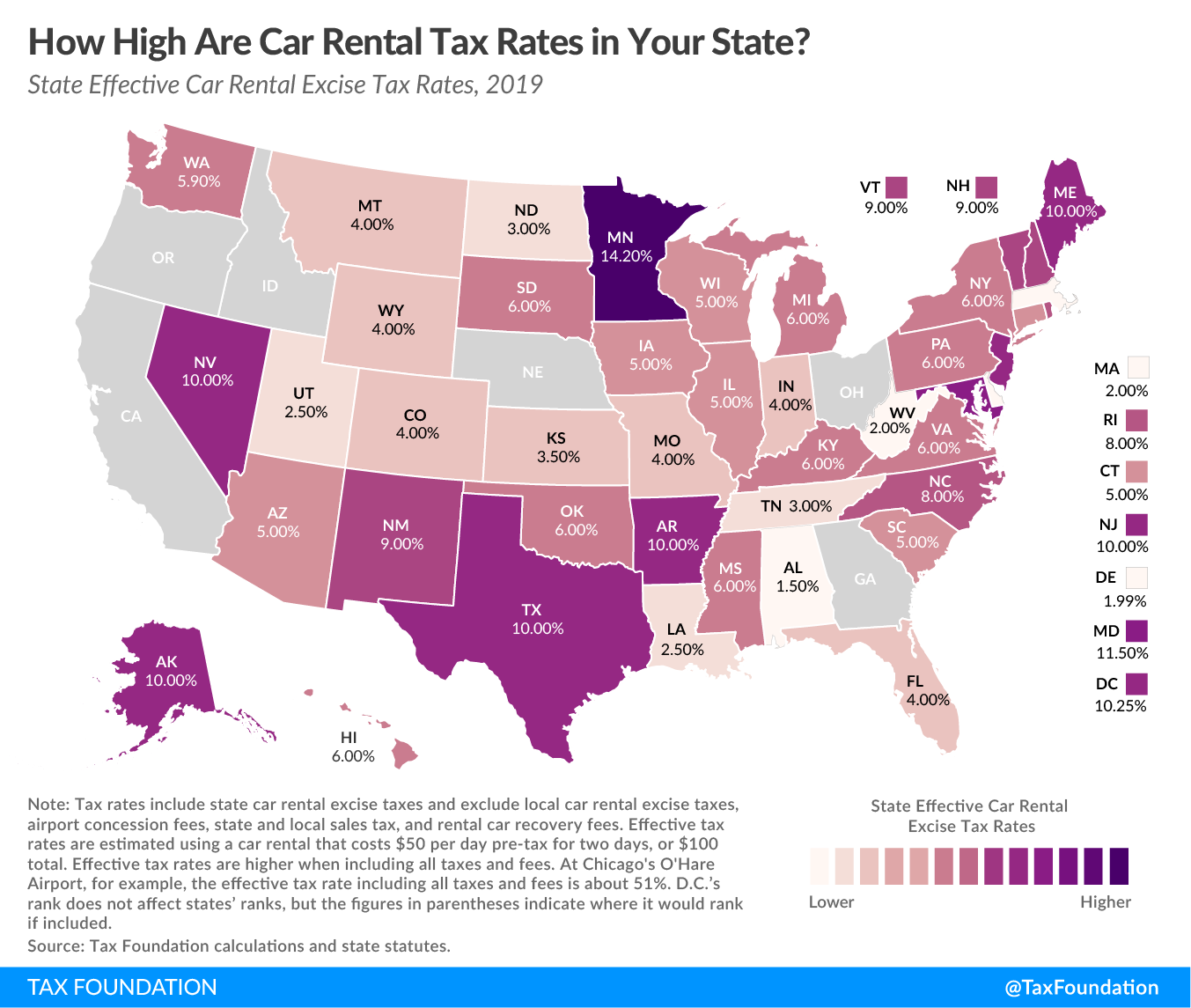

Over the past three decades, excise taxes on car rentals have expanded across the United States. They are levied at the state-level in 44 states, in addition to rental car excise taxes levied by county and municipal governments (see Figure 1 and Appendix Table 1).

A competitive industry with $42 billion in revenue in 2018, car rental companies have thin profit margins and high expenditures to build and maintain a rental vehicle fleet.[4][5] Despite this feature of the industry, car rentals are frequent sources of state and local government revenue.

Figure 1.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeThe Structure of Rental Car Taxes and Fees

As one can see in any rental car contract, car rentals are subject to layers of different taxes and fees that make up a portion of the total bill. Many of these fees are imposed on rental car firms directly, then passed along to the consumer.

One of the most common places where people may need car rentals is at an airport. Local airports may be miles from a traveler’s destination, and in the absence of quality public transit, car rentals are one of the only options available to travelers looking for reliable transportation. Car rentals also afford travelers flexibility that public transit or taxicabs may not provide. As a result, airports across the country have built infrastructure for car rental firms, including dedicated facilities, airport transit, and parking areas. In return, airports often levy several fees on car rental companies wishing to do business at airports. The revenue from these fees may also be shared by municipal and county governments, though this varies by jurisdiction.

The most common types of fees are customer facility charges and airport concession fees, which help fund the direct expenses associated with rental car infrastructure at airports and indirect funding needs for the airport. Rental car companies will pass these fees along to the consumer, calling them “recovery fees.” Rental car companies are regulated by state governments, which often charge these firms higher fees to register and title their vehicles as a method of funding motor vehicle departments. The companies will in turn also pass along these costs to the consumer in the form of license and registration recovery fees.

Separate from airport-related charges and recovery fees, state and local governments levy excise taxes on car rentals. Often, there are multiple excise taxes on car rentals by state, county, and city governments (see Table 1). In Chicago, for example, car rental customers pay a 5 percent Illinois state car rental tax, a 6 percent excise tax levied by the city’s Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority (MPEA), and another 9 percent personal property lease transaction tax levied by the city of Chicago.[6]

State car rental excise taxes are applied on an ad valorem basis, where the tax applies to a percentage of the sale price, or as a flat dollar amount. Thirty-five states and the District of Columbia use ad valorem taxes only, six states assess a flat surcharge, and three states levy both an ad valorem tax and a flat-dollar surcharge. States using a flat-dollar surcharge may levy a one-time tax, as Massachusetts does, or may charge a flat amount per-day, as Hawaii, New Jersey, and West Virginia do. Flat-dollar rates yield higher effective tax rates on less expensive rentals and lower tax rates on more expensive rentals, which can be regressive if a consumer’s income and car rental tastes are related.[7]

States typically distinguish in their statutes whether a car rental excise tax applies to short-term car rentals or to longer-term leases. States may specify that long-term lease arrangements are exempt from car rental excise taxes or they may levy a different rate. For example, Alaska’s 10 percent vehicle rental tax applies to passenger vehicle rentals of 90 consecutive days or less in duration. Leases lasting longer than 90 days are exempt from the tax.[8]

Most states also incorporate car rental transactions into their sales tax base. This is a positive trend, as states have struggled to incorporate services into their sales tax bases, lowering revenue collection and raising sales tax rates on items included in the tax base.[9] Seven states exclude car rentals from state sales tax—Illinois, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Texas, Vermont, and Virginia. Other states offer a state sales tax rate below the general rate. For example, in Mississippi, car rental transactions face a 5 percent state sales tax, not the 7 percent general state sales tax rate.

| State | Locality | Car Rental Excise Tax Levy | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Source: State departments of revenue, state budget offices, county tax departments. Note: (a) Chicago’s Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority (MPEA) levies a 6 percent rental car tax and the city of Chicago levies a 9 percent personal property lease transaction tax. |

|||

| Alaska | Anchorage | 8% | City general fund |

| Arizona | Maricopa County (Phoenix) | 3.5% | Glendale Stadium; youth & amateur sports |

| Arizona | Pima County (Tucson) | $3.50 | Kino Sports Complex |

| Georgia | Atlanta | 10% | State Farm Arena |

| Illinois | Chicago | 6% and 9% transaction tax (a) | City general fund |

| Indiana | Marion County (Indianapolis) | 6% | County general fund |

| Massachusetts | Boston | $10 fee | Convention centers |

| Michigan | Detroit | 2% | Comerica Park |

| Missouri | Kansas City | $4 per day | Sprint Center |

| New York | New York City | 5% | City general fund |

| North Dakota | Grand Forks, Bismarck, Minot | 1% at airports | City general fund |

| Pennsylvania | Philadelphia | 2% | Transportation funding |

| Tennessee | Shelby County (Memphis) | 2% | County general fund |

| Texas | Amarillo, Austin, Euless, El Paso, and Harris County (South Houston) | 5% | Sun Bowl game (El Paso); venues (stadiums, arenas, convention centers); tourist development |

| Utah | Salt Lake County | 7% tourism tax | Tourism, recreation; cultural & convention fund |

| Washington | Pierce (Tacoma), King (Seattle), and Spokane Counties | 1% plus 0.8% transit authority tax | Regional transit (0.8%); sports stadiums or amateur sports activities (1%) |

The number of taxes and fees involved can make it difficult for consumers to determine how their tax dollars are being used. For example, consider a traveler who flies into Honolulu International Airport in Hawaii. The traveler books an economy rental car, paying $57.04 before taxes and fees. After taxes and fees, the traveler pays a total of $75.09, an effective tax rate of 31.06 percent (see Table 2).

|

Source: Tax Foundation calculations and two online rental car company sample bookings. Note: Hawaii’s statutory state excise tax is 4 percent. Hawaii requires firms to collect and remit excise tax on all revenue collected from customers, including on the excise tax collections. This yields an additional 0.166 percent. For more, see Lowell L. Kalapa, “Tax at 4% or 4.166%?” Tax Foundation of Hawaii, Aug. 10, 2003, https://www.tfhawaii.org/wordpress/blog/2003/08/tax-at-4-or-4-166/. |

|

| Rental, Taxes, and Fees | Amount |

|---|---|

| Economy Rental Car (1 Day) | $57.04 |

| Concession Recovery Fee (11.11%) | $6.45 |

| Customer Facility Charge ($4.50/day) | $4.50 |

| Rent Tax Surcharge ($5.00/day) | $5.00 |

| General Excise Tax (4.17%) | $2.69 |

| Honolulu County Tax (0.55%) | $0.35 |

| Total | $75.09 |

Some states are aware of the high effective tax rates they are imposing on car rental consumers and aim to limit how much localities can levy. For example, Washington state permits localities to levy a 0.8 percent motor vehicle excise tax but allows no more than 13.64 percent on sales tax paid on the car rental.[10]

How Rental Car Excise Tax Revenue is Used

Rental car excise tax revenue is used differently in each state. Some states, like North Carolina and Montana, contribute the revenue into a general fund. Others, like New York and Washington, use the revenue to fund transportation projects.[11] Montana raised its rental car tax in 2017 to offset a structural budget deficit.[12] Some state and most local excise taxes on car rentals are used to finance local projects, including stadiums and sports arenas. Over 35 sports stadiums have been funded in part from car rental excise tax revenue.[13]

In addition to stadiums, states and municipalities use the revenue to support tourism-related events. For example, Atlanta, Georgia appropriated $350,000 from its 10 percent car rental tax to support the 2019 Atlanta Jazz Festival.[14] Texas has developed a framework determining how localities can use their rental car excise tax revenue, allocating it to building civic venues, including arenas, stadiums, convention centers, and watershed protection.[15] They are permitted to levy a rental car tax on top of Texas’ 10 percent state car rental tax.

Economic and Tax Policy Consequences of Rental Car Excise Taxes

As car rental taxes and fees have become commonplace, there has been little attention paid to the economic and tax policy rationale. Unlike other excise taxes, policymakers do not aim to reduce the use of rental cars or eliminate a negative externalityAn externality, in economics terms, is a side effect or consequence of an activity that is not reflected in the cost of that activity, and not primarily borne by those directly involved in said activity. Externalities can be caused by either production or consumption of a good or service and can be positive or negative. . While passenger vehicles may create a negative externality in the form of carbon emissions, this is not a special feature of car rentals and is not the justification for their use. Instead, rental car excise taxes are used to export a portion of the tax base onto nonresidents, who bear a disproportionate burden of the tax.

Economic Incidence of Car Rental Excise Taxes

Those offering cars for rent are legally required to collect and remit car rental excise taxes as part of their business obligations. As the example of the visitor at Honolulu International shows, however, the economic incidence of the tax is realized by consumers in the form of higher prices.

Economic theory suggests that the burden of a tax is borne on those who make few adjustments to their behavior in response to the new levy. The demand for car rentals is perceived to be relatively inelastic. This means that consumers will be less sensitive to the change in price introduced by the tax, as they may have few options other than renting a car to get to their destination. The availability of substitutes is one factor that determines a good or service’s elasticity, and with car rentals, they are often one of the only options for transport in rural or suburban areas in the United States.

Though consumers of car rentals may be less sensitive to car rental taxes than those choosing between transit options in their hometowns, this does not mean that car rental taxes have no economic impact. On the contrary, these taxes distort the decision-making of consumers and the economies of the taxing jurisdictions. For example, tax scholars William Gale and Kim Rueben found that a $4 per day rental car levy in Kansas City, Missouri—an effective tax rate of about 13 percent on an economy vehicle—reduced the number of customers at affected branches by 9 percent relative to branches that were unaffected.[16] While consumers had less than a proportionate response to the tax, they altered their behavior by using other transportation options.[17]

Tax Exporting

Car rental excise taxes are a prime example of tax exporting. Tax exporting occurs when state and local governments create tax burdens for nonresidents. Excise taxes on car rentals can be grouped with hotel occupancy taxes, meal taxes, commuter taxes, and tourism taxes as examples of states and localities exporting their tax burden to nonresidents.[18] Tourists paying gas taxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline. , out-of-state corporations paying corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. es, and visitors paying state sales taxes are other examples of tax exporting. Policymakers have an incentive to export tax burdens, as it avoids the political pressure involved when levying new taxes on constituents.

Nonresident travelers and tourists make up a large segment of those using car rental services, though residents also rent cars for their own travel needs. Travelers and tourists bear most of the tax burden, as car rental firms pass on most of the tax burden to consumers. This form of tax exporting is indirect, as it would be a violation of the U.S. Constitution’s Commerce Clause to directly impose a tax burden on nonresidents that is not imposed on residents.[19] Some jurisdictions have tried to go further by enacting car rental taxes that only affect nonresidents, though this tactic was struck down in 2017 when Chicago tried to do so.[20] Hawaii is one of the more creative states, assessing a $3 per day fee for those with a Hawaii driver’s license, but a $5 per day fee for those without one. This effectively charges a higher tax for nonresidents of Hawaii renting cars.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeWhile tax exporting may succeed in disproportionately burdening nonresidents with a rental car tax, the taxes have negative economic effects for the taxing jurisdiction. In addition to lowering the quantity of car rental services demanded, there is evidence that consumers will travel to lower tax jurisdictions nearby, as was the case when Kansas City, Missouri levied a $4 per day rental car tax. Residents and nonresidents alike traveled across the state line to nearby Kansas, which offered a lower effective tax rate on an ad valorem basis, to avoid the tax in Missouri.[21][22] This harmed Kansas City, Missouri’s economy, resulting in missed tax revenue, lower output, and potentially lost jobs in the rental car industry.

Rental car excise taxes, while having a disproportionate effect on nonresidents, also affect residents directly. Residents may rent cars to avoid adding mileage to their own vehicles during long-haul travel, or may rent a vehicle in lieu of owning one for occasional travel needs. In this case, the tax burden is directly felt by residents, who may adjust their behavior and use second-best travel options. This may increase their commuting time, lowering economic growth.

Car Rental Excise Taxes and Tax Policy

In addition to being economically damaging, car rental excise taxes fail the test of sound tax policy for multiple reasons: they violate the tax principle of neutrality, are not connected to taxpayer use of government services, and pose high administrative costs.

Ideally, car rental services would be subject to the same sales and use tax that other goods and services are subject to in a state or locality. Most states have done so, avoiding the broad exemptions that typically apply to other services. By levying additional excise taxes, however, policymakers are narrowly targeting one industry, distorting consumer decision-making and affecting one mode of transportation more heavily than others, such as rail, buses, or trains.

Car rental excise taxes are also disconnected from the benefits the taxpayers receive. As Table 1 illustrates, counties and cities allocate revenue from rental car taxes to unrelated projects, including sports stadiums, amateur sports initiatives, and cultural events. While some of these projects may benefit nonresidents, residents receive most of the benefits given their long-term proximity to the taxing jurisdiction. Contrast this with airport concession fees, which are directly tied to a visitor’s use of the airport facilities. Car rental tax revenue that is used for transportation projects has a closer connection with the benefits visitors receive, but using revenue in this way is not predominate. Visitors also pay gas taxes and tolls, which also fund infrastructure they use while traveling, just like residents. There is no tax policy rationale for why nonresidents should bear a greater cost of infrastructure than residents.

Car rental excise taxes and related fees also pose high administrative costs for localities, firms, and consumers. For example, airport concession fees are used to support airport operations, but occasionally customers are charged these fees even when they book a rental car in a non-airport location.[23] Determining one’s potential tax liability before a trip and weighing different options presents a challenge for consumers, as is the administrative complexity introduced to rental car firms which operate in overlapping tax jurisdictions.

It is appropriate for policymakers to ensure that non-visitors are supporting the government services they benefit from while visiting their city or state. Tourists and travelers provide economic benefits in the form of new jobs, businesses, economic development, and revenue from sales and use taxes. The tax code should provide equal tax treatment for this cohort. Policymakers can get closer to this goal by repealing car rental excise taxes and using alternative revenue sources for government-subsidized projects like sports stadiums.

The Car Rental Tax Regime and the New Economy

The sharing economy has introduced new business models for providing rental car services, which has led to questions surrounding whether and how to incorporate sharing economy firms into the tax and regulatory regime governing car rental companies.

Some car-sharing firms own their own vehicles but provide consumers with flexible rental arrangements, whereby they book a car parked in a nearby neighborhood electronically without having to visit a central car rental facility. Peer-to-peer car-sharing firms, by contrast, do not own their own rental car fleets. Instead, peer-to-peer car-sharing firms provide a platform to facilitate private rental car arrangements. Private individuals may offer their car for rent on the platform, with the platform serving a coordination function in a digital marketplace. This can be compared to ridesharing and short-term rental platforms, which also connect users together. The car-sharing platform charges a fee to users for using it, but otherwise remits income earned to individuals sharing their vehicles with others.

Peer-to-peer car sharing is projected to grow rapidly, from $5 billion in 2016 to $11 billion in 2024—20 percent growth per year.[24] No wonder there is urgency for states to determine how the tax code should treat these new firms.

State Incorporation of Peer-to-Peer Car Sharing into the Tax Code

States are beginning to debate how peer-to-peer car sharing should be incorporated into the state tax code. They are taking different approaches in doing so: interpreting existing statutes to include peer-to-peer car-sharing arrangements or revising rental car tax statutes to include those arrangements.

Some states, such as Alaska, are attempting to use existing car rental tax statutes, arguing that they already apply to peer-to-peer car-sharing firms. While the merits of the legal arguments related to this approach are being tested in the courts, policymakers in these states should reconsider the statutes governing car rentals. Most of these statutes were enacted prior to the emergence of peer-to-peer car sharing. While a reform of the tax code governing car rentals may not be necessary, it could be an opportunity to reevaluate the need for rental car excise taxes in their jurisdiction.

Other states, like Arizona, are considering a revision of their rental car tax statutes to either define peer-to-peer car sharing firms as rental car companies or include peer-to-peer car sharing as a distinct category but subject them to the same tax and regulatory framework that applies to rental car companies.

| State | Proposal | Status |

|---|---|---|

|

Note: *Hawaii charges $0.25 in rental car excise tax per half hour for use up to six hours up to $3/day (for those with a valid Hawaii driver’s license) under their car-sharing tax provision. |

||

| Alaska | N/A | Enforcing existing statute |

| Arizona | SB 1305 applies 5% rental car tax to car-sharing firms HB 2559 creates a separate regulatory and tax structure for peer-to-peer car-sharing firms | Bill pending (SB 1305) Bill pending (HB 2559) |

| California | N/A | Separate provisions for P2P firms |

| Colorado | Extends airport concession fees to car-sharing firms | Bill pending (SB 19-090) |

| Florida | Defines peer-to-peer car sharing as a car rental | Bill pending (SB 1148) |

| Hawaii | N/A | Treats car sharing and car rentals the same for tax purposes* |

| Maryland | N/A | Existing statute regulates peer-to-peer car sharing as a separate market. |

| Minnesota | Exempts car-sharing firms from rental car tax | Bill pending (HF 1357) |

| New Mexico | Repeals the 5% leased vehicle surcharge, requires concession fee agreements with airports

|

Bill pending (SB 556) |

| Ohio | Assesses sales tax and relevant airport concession fees (negotiated by airports) on peer-to-peer car-sharing firms

|

Bill pending (HB 62) |

| Texas | Requires peer-to-peer car-sharing firms to pay rental car excise taxes | Bill pending (HB 2872) |

| Utah | Requires peer-to-peer car-sharing firms to pay rental car excise taxes | SB 190 failed in the Senate |

| West Virginia | Requests a study on the feasibility of peer-to-peer car-sharing regulations (no mention of tax) | HCR 108 was enacted in March 2019 |

While this approach would be straightforward for policymakers, it omits the differences between rental car firms and peer-to-peer car-sharing arrangements. Peer-to-peer car-sharing firms do not rent vehicles to consumers, but instead provide a platform for consumers to connect with one another over vehicle rentals. Individual users are responsible for the maintenance, upkeep, and expenses associated with their vehicles, including the legal responsibility to withhold and file income taxes. Merely redefining peer-to-peer ridesharing firms as rental car companies for tax purposes misses key differences between the two.

There are examples of states taking the right approach. California was a pioneer, as the state has a separate statute governing car sharing, given the differences between those firms and rental car companies.[25] Oregon and Washington also have similar statutes. Both states have taken a sensible approach to clarifying the rules of the game for car-sharing firms, balancing the need for a framework in place without conflating car rental firms and peer-to-peer car-sharing companies. California and Oregon lack state car rental excise taxes, which may have helped defuse some of the tension surrounding related legislation.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeA related policy challenge surrounds the sales tax treatment of rental cars themselves. Rental car companies are usually exempt from paying sales tax when they purchase new rental vehicles. This is the proper tax treatment, as rental vehicles are business inputs. If rental car companies paid sales tax on rental cars, the tax may be passed forward to consumers and generate many of the problems associated with tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action. .[26]

However, individuals who rent their cars on peer-to-peer car-sharing apps may not receive the same exemption, despite using their vehicle for business purposes. The problem is that sales tax provisions are not designed to apply to assets with a mix of business and personal use: either one is an exempt business or a consumer who pays the sales tax.[27]

This issue could be remedied if sales tax could be pro-rated and refunded based on how the asset is used, potentially through existing provisions to apportion vehicle expenses based on business use for income tax purposes. Until a solution is found, peer-to-peer car-sharing companies remain at a relative disadvantage as their users are paying sales tax on assets used for business use.

Peer-to-peer car-sharing firms are also grappling with jurisdictions that would add airport fees to transactions that take place at airports. Users may park their cars in airport garages for pickup or meet at an airport curbside for a vehicle. There is a stronger argument that users of peer-to-peer car arrangements should pay airport fees, as they are using airport facilities. However, it’s unclear if those using peer-to-peer car sharing benefit to the extent car rental companies do, given the latter’s use of dedicated facilities and parking. In some cases, such as in San Francisco, airports do not allow peer-to-peer car-sharing users to use direct drop-off curbside, as it would disadvantage car rental companies.[28] Policymakers and airport authorities could use the example set by working with ridesharing firms at airports to determine a fee structure that makes sense for this type of arrangement.[29]

Creating a Level Tax Code for Car Rental Services

The debate over whether rental car excise taxes should apply to peer-to-peer car-sharing firms and users is a symptom of a broader problem with car rental excise taxes. Discriminatory taxes that target specific firms and industries are bound to be challenged by specific constituencies who have a vested interest in the policy process. States with broad, equitable tax bases that apply to all actors are less likely to be affected by industry lobbying, have fewer economic distortions in their tax codes, and have lower administrative costs.

The successful incorporation of ridesharing firms into the state regulatory, tax, and insurance frameworks over the past six years suggests that there can be a level playing field for peer-to-peer car sharing and rental car firms. That level playing field will not be found by extending a discriminatory and inefficient tax onto more firms, and by extension, customers.

Conclusion

While some policymakers may view car rental excise taxes as a viable revenue source by shifting the tax burden onto nonresidents, these taxes harm residents by driving up the price of local rental cars and curtailing economic growth. Economic evidence shows that travelers and tourists are sensitive to price changes for rental cars and adjust their behavior to avoid the tax.

The growing number of options that travelers have for rental cars, including peer-to-peer car-sharing arrangements, is an opportunity for policymakers to revisit the policy rationale for these discriminatory taxes. Instead of focusing on how excise taxes can be extended onto new business arrangements, states and localities should incorporate rental car transactions into the sales tax base if they have not done so and repeal targeted excise taxes.

Appendix

| State | State Car Rental Excise Tax Rate | Within State Sales Tax Base? | State Sales Tax Rate | State Statute |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Note: Excludes local rental car excise taxes and local sales taxes.Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon do not levy state sales tax.Connecticut’s 9.35 percent sales tax levy is greater than the general state sales tax rate (6.35 percent).Hawaii’s statutory excise tax rate is 4.0 percent, but firms regularly charge 4.16 percent on consumers to recoup excise tax applied to excise tax.Mississippi’s 5.0 percent sales tax levy is lower than the general state sales tax rate (7.0 percent). Source: State statutes and state departments of revenue. |

||||

| Alabama | 1.50% | Yes | 4.0% | Ala. Code § 40-12-222 |

| Alaska | 10% | N/A | N/A (a) | Alaska Stat § 43.52.010. |

| Arizona | 5% | Yes | 5.6% | Ariz. Rev. Stat § 28–5810 |

| Arkansas | 10% | Yes | 6.5% | Ark. Code § 26-63-302 |

| California | None | Yes | 7.25% | N/A |

| Colorado | $2 fee/day | Yes | 2.9% | Colo. Rev. Stat. § 43-4-804(1)(b)(I)(A) |

| Connecticut | 3% plus $1 tourism surcharge/day | Yes | 9.35% (b) | Conn. Gen. Stat. §12-692 |

| Delaware | 1.99% | N/A | N/A (a) | Del. Code Ann. tit. 30, §4302 |

| District of Columbia | 10.25% | Yes | 6.0% | D.C. Code § 47:20-22 |

| Florida | $2/day | Yes | 6.0% | Fla. Stat. §212.0606 |

| Georgia | None | Yes | 4.0% | N/A |

| Hawaii | $3/day for those with a HI driver’s license; $5/day for those without | Yes | 4.0% (c) | Hawaii Rev. Stat. §18-251-2 |

| Idaho | None | Yes | 6.0% | N/A |

| Illinois | 5% | No |

6.25% |

35 ILCS 155 |

| Indiana | 4% | Yes | 7.0% | I.C. § 6-6-9 |

| Iowa | 5% | Yes | 6.0% | Iowa Code § 423.2 |

| Kansas | 3.50% | Yes | 6.5% | Kan. Stat. Ann. § 79-51-17 |

| Kentucky | 6% | No | 6.0% | Ky. Rev. Stat Section 138.460 |

| Louisiana | 2.50% | Yes | 4.45% | LSA-RS 47:551 |

| Maine | 10% | No | 5.50% | 36 M.R.S. §§ 1481-1491 |

| Maryland | 11.50% | No | 6.0% | Md. Code, Tax Law § 03.06.01 |

| Massachusetts | $2 surcharge | Yes | 6.25% | Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 10 §35 EEE |

| Michigan | 6% | Yes | 6.0% | MCL 205.94 |

| Minnesota | 9.2% + 5% fee | Yes | 6.88% | Minnesota Stat § 297A-64 |

| Mississippi | 6% | Yes | 5.0% (d) | Miss. Code Ann. §27-65-231 |

| Missouri | 4% | Yes | 4.23% | Mo. Rev. Stat. §144.020.1 |

| Montana | 4% | N/A |

N/A (a) |

Mont. Code Ann. §15-68-102 |

| Nebraska | None | Yes | 5.5% | N/A |

| Nevada | 10% | Yes |

6.85% |

NRS 482.313 |

| New Hampshire | 9% | N/A | N/A (a) | RSA 78-A |

| New Jersey | $5 fee/day | Yes |

6.63% |

N.J.S.A 18:40-1.1 e |

| New Mexico | 5% (“Leased”) + $2/day | Yes |

5.13% |

N.M. Stat. Ann. §7-14A-3 |

| New York | 6% | Yes |

4.0% |

N.Y. U.C.C. Law § 28-A |

| North Carolina | 8% | Yes | N.C. Gen. Stat § 105-187 | |

| North Dakota | 3% | Yes | 4.75% | N.D. Cent. Code § 57-39.2-03.7. |

| Ohio | None | Yes | 5.75% | N/A |

| Oklahoma | 6% | Yes |

4.5% |

Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 68, § 2110(A) |

| Oregon | None | N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Pennsylvania | 2% + $2 fee/day | Yes |

6.0% |

61 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 47.20 |

| Rhode Island | 8% | Yes |

7.0% |

R.I. Gen. Laws § 31-34.1-2(a) |

| South Carolina | 5% surcharge | Yes | 6.0% | S.C. Code § 56-31-50 |

| South Dakota | 4.5% and a 1.5% tourism tax | Yes |

4.5% |

S.D. Codified Laws §32-5B-20. |

| Tennessee | 3% | Yes |

7.0% |

Tenn. Code Ann. § 67-6-102, 67-6- 202 |

| Texas | 10% | No |

6.25% |

Tex. Admin. Code § 34 1-3.78 |

| Utah | 2.50% | Yes |

6.2% |

Utah Code §59-12-1201 |

| Vermont | 9% | No | 6.0% | 32 V.S.A. § 8903 |

| Virginia | 10% (4% rental tax, 4% local tax, 2% rental fee) | No |

5.3% |

V.A. Code Ann. § 58.1-1736 |

| Washington | 5.90% | Yes |

6.5% |

RCW 82 14-049 |

| West Virginia | $1-$1.50/day | Yes | 6.0%

|

W. Va. Code §17A-3-4 |

| Wisconsin | 5% | Yes | 5.0% | Wis. Stat. § 77.995 |

| Wyoming | 4% | Yes | 6.0% | Wyo. Stat. § 31-19-105(a) |

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNotes

[1] “Travel & Tourism: Economic Impact 2017, United States,” World Travel Tourism Council, March 2017, https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/countries-2017/unitedstates2017.pdf.

[2] Ibid, 6.

[3] “U.S. Travel and Tourism Overview (2017),” U.S. Travel Association, 3, https://www.ustravel.org/system/files/media_root/document/Research_Fact-Sheet_US-Travel-and-Tourism-Overview.pdf.

[4] William G. Gale and Kim Rueben, “Taken for a Ride: Economic Effects of Car Rental Excise Taxes,” Heartland Institute, July 17, 2006, https://www.heartland.org/publications-resources/publications/taken-for-a-ride-economic-effects-of-car-rental-taxes.

[5] “Car Rental Industry in the US,” IBISWorld, November 2018, https://www.ibisworld.com/industry-trends/market-research-reports/real-estate-rental-leasing/car-rental.html.

[6] Brendan Bakala, “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles: Chicago’s High Travel Taxes,” Illinois Policy Institute, December 20, 2017, https://www.illinoispolicy.org/planes-trains-and-automobiles-chicagos-high-travel-taxes/.

[7] William G. Gale and Kim Rueben, “Taken for a Ride: Economic Effects of Car Rental Excise Taxes,” 11.

[8] “Vehicle Rental Tax Historical Overview,” Alaska Department of Revenue – Tax Division, http://www.tax.alaska.gov/programs/programs/reports/Historical.aspx?60255.

[9] Nicole Kaeding, “Sales Tax Base BroadeningBase broadening is the expansion of the amount of economic activity subject to tax, usually by eliminating exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and other preferences. Narrow tax bases are non-neutral, favoring one product or industry over another, and can undermine revenue stability. : Right Sizing a State Sales Tax,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 24, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/sales-tax-base-broadening/.

[10] “Local Taxes,” Washington State Legislature, 123, http://leg.wa.gov/JTC/trm/Documents/TRM_2015%20Update/8%20-%20Local%20Taxes.pdf.

[11] Allison Hiltz and Luke Martel, “Rental Car Taxes,” National Conference of State Legislators, April 2015, http://www.ncsl.org/research/fiscal-policy/rental-car-taxes-lb.aspx.

[12] “The Latest: Businesses Oppose Hotel, Rental Car Tax Increase,” The Seattle Times, Nov. 13, 2017, https://www.seattletimes.com/nation-world/the-latest-committee-hears-little-opposition-to-budget-cuts/.

[13] William G. Gale and Kim Rueben, “Taken for a Ride: Economic Effects of Car Rental Excise Taxes,” 4.

[14] David Pendered, “Atlanta Jazz Festival Funded, Again, with Proceeds of Car Rental Tax at Airport,” Saporta Report, Feb. 5, 2019, https://saportareport.com/atlanta-jazz-festival-funded-again-with-proceeds-of-car-rental-tax-at-airport/.

[15] “Legal Framework for Funding Venues Under the Texas Local Government Code Chapter 334,” City of Austin, http://www.austintexas.gov/edims/document.cfm?id=271689.

[16] Ibid, 5.

[17] If car rental services were elastic, a 13 percent increase in the effective tax rate of the rental car service would yield at least a 13 percent decrease in consumer demand.

[18] Katherine Loughead, “How High Are State and Local Tax Collections in Your State?,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 19, 2018, https://www.taxfoundation.org/state-local-tax-collections-per-capita-2018/.

[19] William G. Gale and Kim Rueben, “Taken for a Ride: Economic Effects of Car Rental Excise Taxes,” 12.

[20] Jared Walczak, “Illinois Supreme Court Strikes Down Chicago Tax on Car Rentals Outside Chicago,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 23, 2017, https://www.taxfoundation.org/illinois-supreme-court-strikes-down-chicago-tax-car-rentals-outside-chicago/.

[21] William G. Gale and Kim Rueben, “Taken for a Ride: Economic Effects of Car Rental Excise Taxes,” 19.

[22] Prospective rental car customers may choose to pay the car rental excise tax if the time or monetary cost associated with traveling to a lower-tax jurisdiction is greater than the benefit of avoiding the higher tax.

[23] Christopher Elliott, “Bizarre New Car Rental Trick: An Airport Fee for a Non-Airport Rental,” Elliott Advocacy, June 30, 2009, https://www.elliott.org/blog/bizarre-new-car-rental-trick-an-airport-fee-for-an-non-airport-rental/.

[24] Alison Griswold, “Startups like Uber Decimated Taxi Companies. Rental Companies are Next,” Quartz, May 10, 2018, https://www.qz.com/1253717/turo-is-doing-to-rental-car-companies-what-uber-did-to-taxis-and-theyre-scared/.

[25] Neal Gorenflo, “California’s P2P Car-Sharing Bill Signed Into Law,” Shareable, Sept. 29, 2010, https://www.shareable.net/blog/californias-p2p-car-sharing-bill-signed-into-law.

[26] Garrett Watson, “Resisting the Allure of Gross Receipts Taxes: An Assessment of Their Costs and Consequences,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 6, 2019, https://www.taxfoundation.org/gross-receipts-tax/.

[27] For an overview of similar challenges in the tax code, see Shu-Yi Oei and Diane M. Ring, “Can Sharing Be Taxed?” Washington University Law Review 93, no. 4 (2016), http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol93/iss4/7.

[28] Eric Boehm, “America’s Biggest Rental Car Company Is Lobbying to Drive Away Competitors,” Reason, August/September 2018, https://reason.com/archives/2018/07/12/americas-biggest-rental-car-co.

[29] For an example, see Kelly Yamanouchi, “Uber X, Lyft Set for Legal Pickups at Atlanta Airport,” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Dec. 29, 2016, https://www.ajc.com/business/uber-lyft-set-for-legal-pickups-atlanta-airport/XRVgS1swlof0a1FVQ0bPOO/.

Share