Key Findings

- Policymakers are currently focused on revenue neutral corporate taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reform to bring down the high U.S. statutory corporate tax rate.

- Corporate-only tax reform leaves out nearly 95 percent of all businesses from tax reform.

- Revenue neutral corporate tax reform that eliminates business tax expenditures in exchange for a 25 percent corporate tax rate could increase taxes on pass-through businesses.

- Using the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth economic model, we estimate that revenue neutral corporate tax reform that increases taxes on pass-through businesses would reduce the size of the economy by 0.2 percent or $36 billion in the long run due to the increased cost of capital in the pass-through sector.

- In isolation, the impact of the elimination of business tax expenditures for pass-through businesses has a significant negative impact on the economy, reducing GDP by 0.5 percent or $84 billion in the long run.

Introduction

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have recognized that the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate should be lowered. The United States has an uncompetitive corporate tax code. It levies a high marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. of 39.1 percent (combined federal and state) on corporate income, which is now the highest corporate income tax rate in the industrialized world. Meanwhile, countries throughout the world have been lowering their corporate income tax rate to an average around 25 percent. This has made it more difficult for U.S. businesses to compete both internationally and domestically.[1]

Many policymakers, however, want to accompany lower corporate tax rates with other changes that would increase business taxes in order to maintain revenue neutrality.[2] This type of tax reform gets around difficult issues surrounding how to reform the individual tax code. However, corporate-only tax reform comes with other challenges.

One issue is that corporate-only tax reform leaves a significant amount of businesses out of tax reform. Currently in the United States, 95 percent of all businesses are what are called pass-through businesses.[3] These businesses do not pay taxes through the corporate income tax code, instead, they pay through the individual income tax code. As a result, they would not see any benefit from a corporate rate reduction.

In addition, revenue neutral corporate tax reform could actually increase taxes on pass-through businesses. In order to pay for a lower corporate tax rate, corporate reform may eliminate business tax expenditures widely used by all businesses, while maintaining current tax rates on pass-through businesses.

In this paper, we model the impact of a revenue neutral corporate rate reduction that increases taxes on pass-through businesses. We measure the effect of the trade-off on GDP, wages, employment, and the cost of capital for both pass-through businesses and corporations. We also isolate the economic impact of the elimination of specific tax expenditures for pass-through businesses.

Nearly 95 Percent of All Businesses Would Not Benefit from Corporate-Only Tax Reform

One of the main issues surrounding corporate-only tax reform is that it does not attempt to reform the tax code for the majority of businesses in the United States.

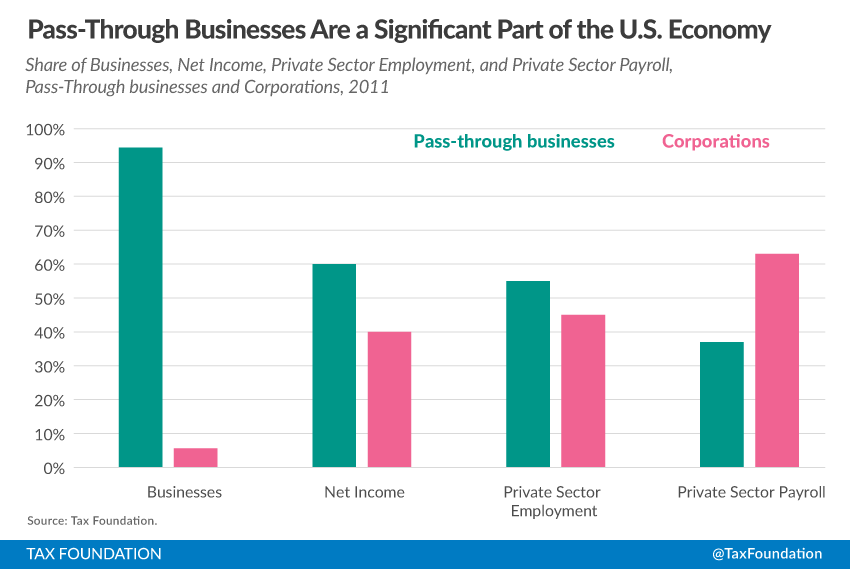

The United States currently has a large number of pass-through businesses, which pay their taxes through the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. code. These sole proprietorships, S-corporations, and partnerships make up about 93.4 percent of all businesses (Chart 1).[4] Sole proprietorships comprise the majority. According to Census data, 73.1 percent of all businesses were sole proprietorships (20.3 million firms), 13.1 percent of all businesses were S corporations (3.65 million firms), and about 8 percent were partnerships (2.2 million firms) in 2011. C-corporations only made up 5.6 percent of all businesses in the United States (1.5 million firms).

Chart 1.

Not only are pass-through businesses the vast majority of all businesses, they account for a significant amount of economic activity in the United States. In 2011, pass-through businesses earned about 60 percent of net business income in the United States. In addition, they account for 55 percent of all private sector employment, or 65.7 million workers, in the United States and nearly 40 percent, or $1.65 trillion, of all private sector payroll.[5]

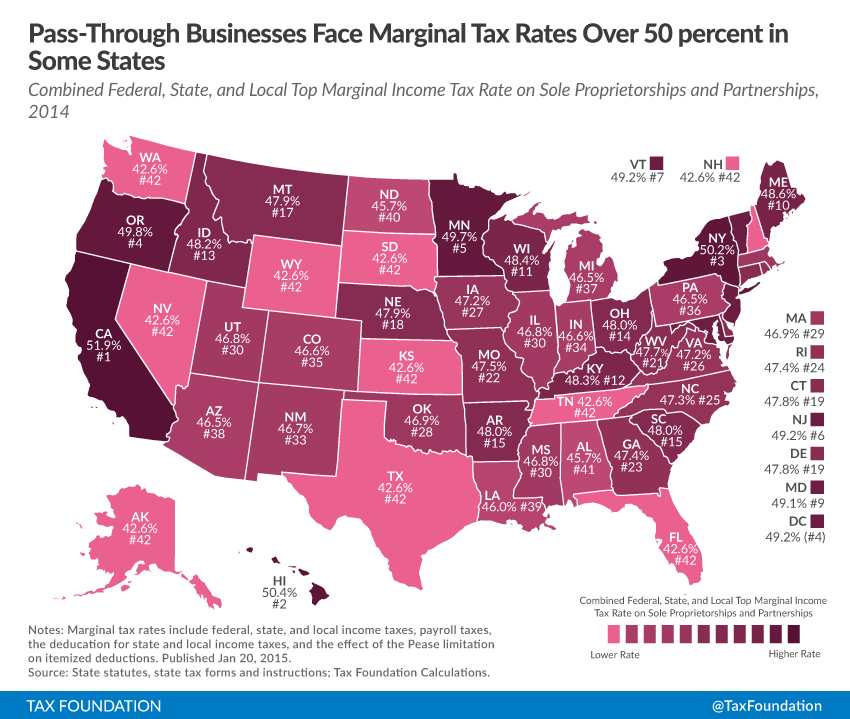

Currently, pass-through businesses can face high marginal tax rates on their income. Since these businesses pass their income and losses directly to their owners, these businesses face the same marginal tax rates as individuals. The individual income tax, payroll or self-employment taxes, the Affordable Care Act Net Investment Income Tax, and in many cases the Alternative Minimum Tax, can combine to impose high effective tax rates on pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income. If you combine federal tax rates with often high state and local taxes, pass-through business income can face top marginal tax rates over 50 percent in many states (Chart 2).

Chart 2.

Revenue Neutral Corporate Tax Reform Almost Has to Raise Taxes on Pass-Through Businesses

In addition to the fact that a corporate tax rate reduction does not benefit pass-through businesses, it is possible that revenue neutral corporate tax reform could actually increase taxes on pass-through businesses. This is because many of the provisions that lawmakers are looking to eliminate in order to reduce the corporate tax rate may impact pass-through businesses in some way.

As a practical matter, most corporate tax expenditures have individual-side counterparts that pass-through businesses also use. Thus, eliminating them in order to raise revenue will also raise taxes on pass-through businesses. For example, moving from the current Modified Accelerated Cost RecoveryCost recovery is the ability of businesses to recover (deduct) the costs of their investments. It plays an important role in defining a business’ tax base and can impact investment decisions. When businesses cannot fully deduct capital expenditures, they spend less on capital, which reduces worker’s productivity and wages. System (MACRS) to the Alternative Depreciation System (ADS) for machinery would raise a total of $306 billion over the next decade according to the FY 2016 budget. A majority (63 percent) of that revenue would come from corporations, but 37 percent of that revenue would come from pass-through businesses (Chart 3).

Chart 3.

Lawmakers could attempt to mitigate the potential impact on pass-through businesses by keeping some business tax provisions on the individual side that would be limited on the corporate side. However, this would create further tax disparity between business forms and create unneeded complication. For example, it would create two different depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. regimes for two different forms of business.

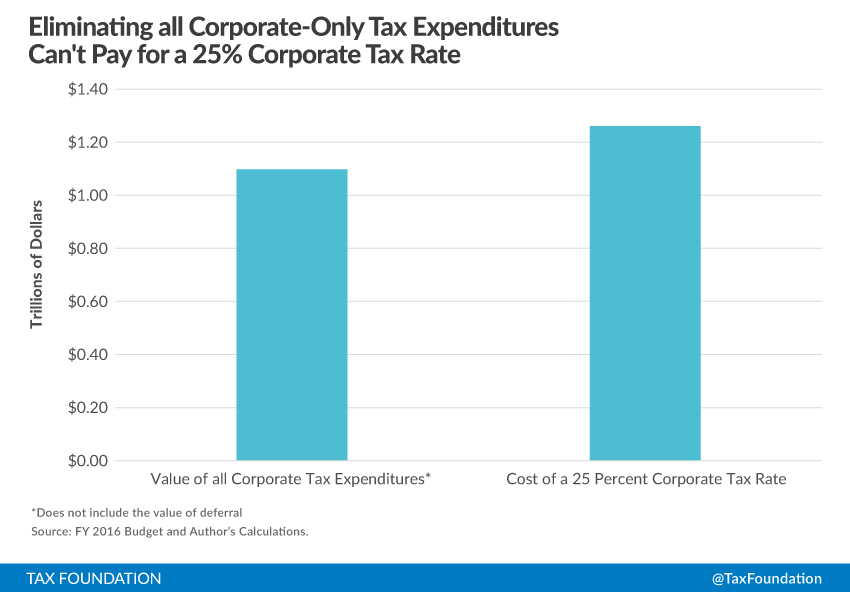

On top of the practical limitations of eliminating business provisions for only corporations, there is simply not enough revenue from the elimination of just corporate-side tax expenditures to reduce the corporate income tax rate to 25 percent (Chart 4). The cost of reducing the corporate income tax to 25 percent on a static basis (assuming the corporate tax cut does not alter GDP) would be about $1.26 trillion or an average or $126 billion per year.[6] Leaving aside the deferral of taxes on U.S. multinational foreign income, which should be reserved for international reform, the total value of all corporate-only tax expenditures is approximately $1.09 trillion over ten years according to the FY 2016 budget.

Chart 4.

The Elimination of Certain Tax Expenditures for Pass-Through Businesses Would Impact Their Incentive to Invest

There are a number of ways that lawmakers could make up the needed revenue for revenue neutral corporate tax reform. Some of the methods could have smaller impacts on pass-through businesses and the economy than others.

For the purposes of this analysis, we will focus on a group of business-only tax expenditures that could be targeted for revenue neutral corporate tax reform. It is important to evaluate these tax expenditures based on how their complete elimination would raise additional revenue necessary to reduce the corporate income tax rate, how they could impact pass-through businesses but not individuals’ nonbusiness income, and how they could impact the economy as a whole (Appendix Table 1).

In total, there are 18 business-only tax expenditures that revenue neutral reform may attempt to eliminate on both the corporate and individual side of the tax code. The largest of these tax expenditures for pass-through businesses is accelerated depreciation for machinery, with a ten-year value of $111 billion for pass-through businesses. The second largest business-only tax expenditureTax expenditures are a departure from the “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses, through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. Expenditures can result in significant revenue losses to the government and include provisions such as the earned income tax credit (EITC), child tax credit (CTC), deduction for employer health-care contributions, and tax-advantaged savings plans. on the individual side is the deduction for U.S. production activities, or Section 199. This provision has a $38 billion value for pass-through businesses over the next decade. The remaining 16 provisions that affect decisions on the margin have a value of $51 billion.

In total, if lawmakers were to eliminate these business tax provisions and a number of smaller provision across the board (for both corporations and pass-through businesses), they would be able to raise an additional $200 billion that they would need to lower the corporate income tax rate to 25 percent (Chart 5).

Chart 5.

It is also important to analyze these 18 business-only provisions, specifically, because their elimination for pass-through businesses would have the largest impact on the incentive to invest. These tax expenditures are those that either correct for double-taxation in the tax code, move the tax code toward a neutral tax base, or are equivalent to a tax rate cut for some businesses. Eliminating these tax expenditures affect a business’s incentive to invest on the margin. For example, the elimination of MACRS lengthens assets lives for capital investments. This increases the marginal tax rate on an investment’s return, reducing a business’s incentive to invest.

Tax expenditures that do not fall into this category are either subsidies for specific activities or social policies and generally do not impact the incentive to invest. While their elimination for pass-through businesses would raise revenue, their absence would have little to no impact on the economy as a whole. Policies like these include the New Markets tax credit, exemption of credit union income, and Recovery Zone Bonds. Eliminating these provisions may be politically difficult due to either bipartisan support or the fact that they are used by more than just businesses, meaning that their elimination would increase taxes on individuals. However, if tax provisions with limited economic value were eliminated, instead of business tax expenditures that move the tax code toward a cash-flow tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , it would reduce the negative impact of a revenue neutral corporate tax reform on the economy.

Modeling the Elimination of Business Tax Expenditures for Corporations and Pass-Through Businesses

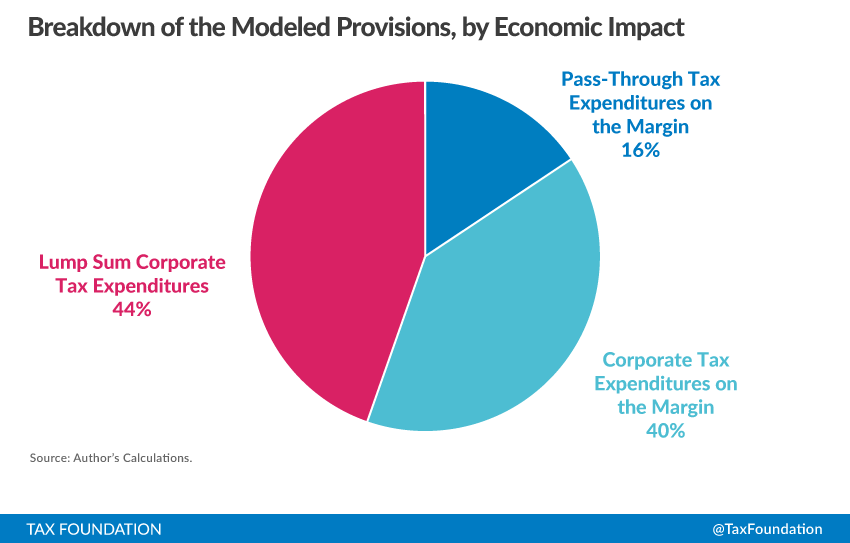

In order to model the impact of the elimination $1.3 trillion in business tax expenditures (about $1.1 trillion for corporations and $200 billion for pass-through businesses), business tax expenditures need to be broken into three groups.

The first group of tax expenditures represent corporate tax expenditures that impact investment on the margin. These tax expenditures are those included in Appendix Table 1. These provisions (with the exception of the accelerated depreciation provisions which are modeled more precisely in the model), are modeled as corporate income tax rate equivalents. These account for 40 percent of the provisions modeled.

Chart 6.

The second group of provisions are those that impact pass-through businesses on the margin. As with the corporate proposals (again, excluding accelerated depreciation), they are modeled as marginal tax rate increases. These provisions are also highlighted in Appendix Table 1. In total, these provisions account for 16 percent of the provisions modeled.

The final group are considered lump-sum corporate tax expenditures. These tax expenditures either do not impact the incentive to invest on the margin, or are subsidies to specific industries that simply shift around economic activity. The elimination of these provisions have little to no impact on the economy (Appendix Table 2).[7]

Revenue Neutral Corporate Tax Reform That Increases Taxes on Pass-Through Businesses Could Shrink the Economy

Using the Taxes and Growth economic model, we estimate the impact of a corporate tax rate reduction to 25 percent while eliminating all corporate-side tax expenditures. In addition, we assume that lawmakers eliminate the 18 business tax expenditures across the board for both corporations and pass-through businesses.

Even with a 25 percent corporate income tax rate, a trade-off like this would end up reducing the size of GDP by 0.2 percent, or $36 billion in the long run. As a result of the smaller economy, wages would be 0.2 percent lower with 32,000 fewer jobs at the end of the adjustment period.

|

Table 1. Potential Economic Impact of Revenue Neutral Corporate Tax Reform |

|

|

GDP |

-0.20% |

|

GDP $ |

-$36 |

|

Wage Rate |

-0.20% |

|

Employment |

-32,000 |

|

Change in cost of Capital |

|

|

Corporate |

-0.70% |

|

Non-corporate |

3.00% |

|

All Business |

0.40% |

|

Source: Tax Foundation. |

The impact of this trade-off on total investment and economic growth can be seen in how it affects the cost of capital for each business form. This trade-off would decrease the corporate tax rate enough to just about offset the increased cost of capital from lost tax expenditures. Thus, the cost of capital for corporations would decline slightly (a reduction of 0.7 percent). However, since pass-through businesses do not see an offsetting rate cut to their broader tax base, their cost of capital increases by 3.0 percent. In total, the increased cost of capital for pass-through businesses more than offsets the decrease for corporations, resulting in an increase in the cost of capital across all business investment (corporate and pass-through) by 0.4 percent.

Chart 7.

Isolating the Impact of Revenue Neutral Corporate Tax Reform on Pass-Through Businesses

As the above analysis indicates, revenue neutral corporate tax reform increases the cost of capital for pass-through businesses by 3 percent. If we look at this increase in the cost of capital on the economy by itself, we can isolate the economic impact that the elimination of these tax expenditures for pass-through businesses has on the economy as a whole.

The higher cost of capital for pass-through businesses without an offsetting reduction from corporate-side reforms would mean a higher cost of capital of 0.9 percent across the economy. The increase in the cost of capital would lead to lower investment in the future and result in a 0.5 percent, or $84 billion, smaller economy in the future. In addition, wages would be 0.5 percent lower and employment would be decreased by 82,000 jobs.

|

Table 2. The Impact of a Broader Tax Base for Pass-Through Businesses on the Economy |

|

|

GDP |

-0.50% |

|

GDP$ |

-$84 |

|

Wages |

-0.40% |

|

Employment |

-82,000 |

|

Change in the Cost of Capital |

|

|

Corporate |

0% |

|

Non-corporate |

3.00% |

|

All Business |

0.90% |

|

Source: Tax Foundation. |

Conclusion

It is certainly a worthwhile goal to reduce the corporate income tax rate from its current 35 percent to 25 percent. However, there are several issues with a revenue neutral package to lower the corporate income tax rate. One of the major issues is that a corporate-only reform leaves out a majority of businesses that pay their taxes through the individual code. In addition, revenue neutral corporate reform will likely increase taxes on these pass-through businesses.

Using the Taxes and Growth economic model, we show that revenue neutral corporate tax reform that eliminates tax expenditures for both corporations and pass-through businesses results in a 0.2 percent smaller economy even through the corporate income tax rate was reduced to 25 percent. We also show that the impact of the elimination of business tax expenditures for pass-through businesses with no rate offset could reduce the size of the economy by 0.5 percent.

Appendix

|

Appendix Table 1. Business Tax Expenditures with Net Economic Impact, Corporate and Individual Ten-Year Value (Millions of Dollars) |

|||

|

Business Tax Expenditures that Impact Decisions at the Margin |

Total |

Corporate |

Individual |

|

Accelerated depreciation of machinery and equipment |

$306,810 |

$194,820 |

$111,990 |

|

Deduction for US production activities (Section 199) |

$178,740 |

$140,090 |

$38,650 |

|

Expensing of research and experimentation expenditures |

$75,550 |

$70,250 |

$5,300 |

|

Inventory property sales source rules exception |

$58,480 |

$58,480 |

$0 |

|

Accelerated depreciation on rental housing |

$32,350 |

$5,690 |

$26,660 |

|

Last-in, First-out (LIFO) Accounting |

$19,000 |

$16,000 |

$3,000 |

|

Excess of percentage over cost depletion, fuels |

$13,630 |

$10,900 |

$2,730 |

|

Expensing of certain small investments |

$7,280 |

$640 |

$6,640 |

|

Excess of percentage over cost depletion, nonfuel minerals |

$6,620 |

$6,170 |

$450 |

|

Expensing of exploration and development costs, fuels |

$6,220 |

$4,990 |

$1,230 |

|

Expensing of certain multiperiod production costs |

$4,570 |

$330 |

$4,240 |

|

Expensing of multiperiod timber growing costs |

$4,090 |

$2,590 |

$1,500 |

|

Expensing of certain capital outlays |

$2,630 |

$190 |

$2,440 |

|

Amortize all geological and geophysical expenditures over 2 years |

$1,130 |

$930 |

$200 |

|

Expensing of reforestation expenditures |

$1,040 |

$320 |

$720 |

|

Natural gas distribution pipelines treated as 15-year property |

$980 |

$980 |

$0 |

|

Tonnage tax |

$880 |

$880 |

$0 |

|

Expensing of exploration and development costs, nonfuel minerals |

$830 |

$100 |

$730 |

|

Total, Expenditures that Impact Cost of Capital |

$720,830 |

$517,050 |

$203,780 |

|

Note: The 2016 budget does not indicate that LIFO is a tax expenditure, but JCT does. It is included because it has been targeted several times as a possible revenue source for a corporate rate reduction. Source: FY 2016 Budget. |

|

Appendix Table 2. Corporate-only Tax Expenditures with Little to No Net Economic Impact (Millions of Dollars) |

|

|

Tax Expenditure |

Ten-Year Cost |

|

Exclusion of interest on public purpose State and local bonds |

$139,170 |

|

Credit for low-income housing investments |

$83,610 |

|

Exclusion of interest on life insurance savings |

$81,370 |

|

Tax credit for orphan drug research |

$38,870 |

|

Graduated corporation income tax rate (normal tax method) |

$38,300 |

|

Exemption of credit union income |

$25,390 |

|

Special ESOP rules |

$21,520 |

|

Deductibility of charitable contributions, other than education and health |

$21,170 |

|

Credit for increasing research activities |

$18,300 |

|

Exclusion of interest on hospital construction bonds |

$16,730 |

|

Energy production credit |

$12,100 |

|

Exclusion of interest on bonds for private nonprofit educational facilities |

$10,980 |

|

Deductibility of charitable contributions (education) |

$10,100 |

|

Tax exemption of certain insurance companies owned by tax-exempt organizations |

$8,460 |

|

Exclusion of interest on owner-occupied mortgage subsidy bonds |

$6,030 |

|

Tax incentives for preservation of historic structures |

$5,590 |

|

Advanced nuclear power production credit |

$5,210 |

|

Exclusion of interest on rental housing bonds |

$4,910 |

|

New markets tax credit |

$4,630 |

|

Exclusion of interest for airport, dock, and similar bonds |

$3,630 |

|

Special Blue Cross/Blue Shield deduction |

$3,550 |

|

Deductibility of charitable contributions (health) |

$2,850 |

|

Exclusion of interest on student-loan bonds |

$2,450 |

|

Exclusion of interest on bonds for water, sewage, and hazardous waste facilities |

$2,200 |

|

Qualified school construction bonds |

$1,440 |

|

Exemption of certain mutuals’ and cooperatives’ income |

$1,340 |

|

Credit to holders of Gulf Tax Credit Bonds |

$1,100 |

|

Energy investment credit |

$1,080 |

|

Credit for holders of zone academy bonds |

$1,060 |

|

Work opportunity tax credit |

$960 |

|

Exclusion of utility conservation subsidies |

$880 |

|

Exclusion of interest on small issue bonds |

$810 |

|

Credit for investment in clean coal facilities |

$760 |

|

Recovery Zone Bonds |

$590 |

|

Deductibility of medical expenses |

$460 |

|

Small life insurance company deduction |

$430 |

|

Deferral of gain on sale of farm refiners |

$420 |

|

Exclusion of interest on bonds for water, sewage, and hazardous waste facilities |

$320 |

|

Social Security benefits for retired workers |

$270 |

|

Exclusion of interest on bonds for Highway Projects and rail-truck transfer facilities |

$250 |

|

Tribal Economic Development Bonds |

$200 |

|

Tax credits for clean-fuel burning vehicles and refueling property |

$190 |

|

Credit for disabled access expenditures |

$190 |

|

Deduction for endangered species recovery expenditures |

$180 |

|

Special alternative tax on small property and casualty insurance companies |

$170 |

|

Premiums on group term life insurance |

$160 |

|

Credit for holding clean renewable energy bonds |

$150 |

|

Exclusion of interest on energy facility bonds |

$100 |

|

Qualified energy conservation bonds |

$100 |

|

Investment credit for rehabilitation of structures (other than historic) |

$100 |

|

Exclusion of interest on veterans housing bonds |

$100 |

|

Deductibility of student-loan interest |

$70 |

|

Employer-provided child care credit |

$40 |

|

Self-employed plans |

$30 |

|

Education Individual Retirement Accounts |

$30 |

|

Capital gains exclusion on home sales |

$20 |

|

Note: Expenditures with zero or negative value dropped. Source: FY2016 Budget Data. |

[1] OECD Tax Database, Table II.1 Corporate Income Tax Rates: Basic/Non-Targeted, http://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/tax-database.htm#C_CorporateCaptial.

[2] Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2016 Budget of the U.S. Government, Feb. 2, 2015, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2016/assets/budget.pdf.

[3] Kyle Pomerleau, An Overview of Pass-through Businesses in the United States, Tax Foundation Special Report No. 227. Jan. 21, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/article/overview-pass-through-businesses-united-states.

[4] Pomerleau, supra note 3.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model.

[7] Tax expenditures with zero or negative value dropped.