On October 29, 2018, Chancellor Philip Hammond of the United Kingdom presented his budget to Parliament. The budget lays out a view towards a post-Brexit UK and has several tax policies designed with that transition in mind.

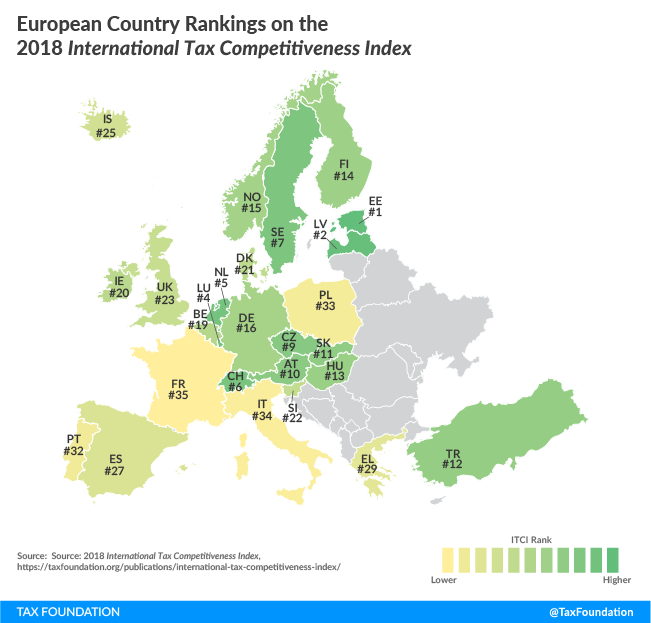

The UK ranks 23rd on our 2018 International Tax Competitiveness Index (ITCI) due to several poorly designed taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. policies. These weaknesses include the current inability for businesses to write off costs related to investments in structures and a poorly designed VAT system that only captures 44 percent of the potential tax base. The UK also has multiple distortionary property taxes with separate levies on real estate, estates, assets, and financial transactions.

[global_newsletter_inline_widget campaign=”//TaxFoundation.us1.list-manage.com/subscribe/post?u=fefb55dc846b4d629857464f8&id=6c6b782bd7&SIGNUP=ITCI”]

The UK tax system does have some strengths, though. The current corporate rate is at 19 percent, below the OECD average of 23.9 percent. The UK also has the broadest tax treaty network in the OECD with 131 tax treaties and a territorial tax system that exempts foreign dividends and capital gains from taxation.

The tax proposals in the recent budget would make several changes that could impact the competitiveness of the tax code.

Two pro-growth reforms

Some of the proposals that would improve the corporate tax system include:

- Lowering the corporate rate to 17 percent in 2020 from the current 19 percent

- Two percent capital allowanceA capital allowance is the amount of capital investment costs, or money directed towards a company’s long-term growth, a business can deduct each year from its revenue via depreciation. These are also sometimes referred to as depreciation allowances. on new nonresidential structures and buildings, allowing businesses to recover 27.9 percent of the costs from those investments

These two proposals would boost the UK’s overall ranking on the ITCI from 23rd to 17th. However, the UK would continue to rank 34th out of 35 (just ahead of Chile) on the ITCI’s measure of cost recovery for business investments.

The provision affecting investments in buildings and structures is a partial reversal of the harmful base broadening that the UK recently went through. Poorly designed write-offs ignore investment costs and inflate the tax bills that businesses face. These provisions continue to damage the long-term growth prospects for the UK.

Business investment is critical to long-term growth, and the UK could choose to attract more investment by expanding business investment provisions even further. The government could even do so in a revenue neutral manner by augmenting asset depreciation schedules in a way that accounts for the time value of money and a required return on investment.

Two steps in the other direction

Other proposals in the budget would introduce new layers of complexity and distortions. These include:

- New digital services tax (DST) on revenues of large social media platforms, online marketplaces, and search engines

- New tax on income from intangible property (IP) held offshore by foreign multinationals with sales in the UK

The DST is like one proposed in March 2018 by the European Commission which has been widely criticized. The UK would apply a 2 percent tax on revenues of search engines, social media platforms, and online marketplaces with more than £500 million (US $638 million) revenues from digital services. The first £25 million (US $32 million) in revenues would be exempt from tax. Additionally, companies with net operating losses would not be required to pay the tax and companies with low profit margins would face a reduced rate.

Chancellor Hammond says that this tax would be temporary and would be removed if an appropriate international solution is reached on digital taxation.

Unfortunately, this tax would be discriminatory, distortionary, and difficult to administer. It discriminates against firms that operate in the sectors it applies to relative to other industries. It distorts choices businesses face as they approach the £500 million (US $638 million) threshold at which the tax would apply, and it would punish loss-making businesses when they are finally able to turn a profit.

The government estimates that just £440 million (US $574 million) would be raised from this tax in the 2024 fiscal year. The potential expiration of the tax makes the administration of implementing and complying with the DST seem as if it might not be worth the revenues the tax could raise.

The new tax on income from IP is yet another wrinkle that many international tech firms that operate in the UK would have to navigate. The tax would effectively reach into the jurisdictions where some intellectual property is held and directly tax offshore entities. Some income would be exempt from this policy if there were sufficient business substance in the offshore location where the IP is held or if the UK had a double tax treaty with the jurisdiction that includes a nondiscrimination provision.

This tax would likely result in many companies choosing to shift some IP from certain jurisdictions to others to minimize their tax burden. In fact, the revenue estimate for this proposal takes into account the likelihood that the behavior of multinational companies would change so that this new tax would collect less revenue each year it is in place than the prior year. Ultimately, for the 2024 fiscal year, the UK government expects to collect just £165 million (US $215 million) from this tax.

Three targeted tax cuts

A third category of proposals include a set of tax cuts:

- Increasing personal allowances from £11,850 (US $15,458) to £12,500 (US $16,306)

- Increasing threshold at which the 40 percent personal income tax rate applies from £34,500 (US $45,005) to £37,500 (US $48,919 million)

- Reducing property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. rates faced by 90 percent of retailers (business rates reduction)

Targeted tax cuts can help to alleviate the tax burden that certain groups face and can be steps toward a more neutral and competitive tax policy. By increasing personal allowances and the threshold at which the 40 percent income tax rate applies, the UK is lowering the tax burden that some workers will face.

The tax cut for retailers will provide businesses with certain levels of market rent direct tax relief. However, the policy creates a serious tax cliff with businesses that have rent just below and above £50,000 (US $62,225) with business rates tax liability difference of an estimated £9,010 (US $11754). Cliffs like these can create serious economic distortions, with some businesses likely forgoing certain property improvements to avoid a higher tax bill should they cross the threshold.

Property tax regimes that apply tax to improvements on land like buildings and real property as well as the land itself are economically inefficient. A better policy would be to apply tax to the value of the land instead of buildings or other improvements to the land.

[global_newsletter_inline_widget campaign=”//TaxFoundation.us1.list-manage.com/subscribe/post?u=fefb55dc846b4d629857464f8&id=6c6b782bd7&SIGNUP=ITCI”]

A budget for growth?

If the UK is seeking to become more competitive post-Brexit and adopt tax policies that help businesses grow and hire, then the government should avoid taxes that punish investment and instead work to attract businesses that will invest for the long term. The challenges of Brexit will require the UK to have a competitive tax policy to secure opportunities for growth.

Complex regimes targeted at multinationals and tech companies will likely have a chilling effect on investment. Capital investments by tech firms is already low in Europe, and the UK should avoid policies that would worsen that reality.

A strong move towards allowing businesses to recover their investment costs could truly set the UK apart as a destination for businesses that are looking to grow and hire. Targeted tax relief may be part of a solution as well, but the UK should be thinking much bigger than a few tax cuts. Fundamental tax reform with a focus on business investment could change the landscape for the UK’s growth prospects, but such policy proposals are not to be found in this current budget.

Share this article