On October 10, the OECD Secretariat released a proposal on Pillar 1 of the project to address taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. challenges from the digitalization of the economy. The Secretariat’s proposal is designed to adopt elements from three prior competing proposals and facilitate further discussion and potential compromise among the more than 130 countries engaged in the project.

The proposal is open for public consultation with a deadline for written comments on November 12 and a public consultation in Paris on November 21 and 22.

Currently, businesses pay taxes in countries where they have permanent establishments according to both domestic laws and international rules. For firms that rely heavily on highly valued intangible assets, physical presence is not necessary to be able to reach many markets. As more and more businesses become able to sell into various markets around the world without owing corporate income tax in those jurisdictions, countries have been pushing for a different way to tax those businesses.

The Secretariat’s proposal outlines new methods for allocating taxing rights among countries, provides some thresholds and definitions for which companies might be impacted by the proposal, and has three separate categories of taxable profits that could be used to provide new taxing authority or create a baseline for taxing certain activities.

Those categories are as follows:

- Amount A: the deemed residual (non-routine) profit allocated to market jurisdictions

- Amount B: a fixed return for marketing and distribution activities in market jurisdictions

- Amount C: (i) additional amount beyond Amount B that should be taxed in a market jurisdiction, and (ii) binding and effective dispute prevention and resolution to minimize double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. occurring under any of the elements.

Taken together, these amounts would reallocate taxing rights in various circumstances and change where many multinational businesses pay taxes. The overall amount many businesses would pay could also change if there is a difference in tax rates across the countries in which the business operates.

The complexity behind the proposal and the thresholds and definitions will create a host of new incentives that will impact the way businesses choose to structure themselves in the global economy. It is important to examine both how the proposal could interact with decisions by businesses and tax authorities and the economics of those changes.

Thresholds and Scope

The document lays out several concepts that will impact which companies are affected and how much they will need to pay. First, the proposal states that “consumer-facing” businesses are the focus. Businesses in extractive industries are assumed to be not within this scope, and digital businesses that have a consumer-facing platform are expected to be in scope even if their sales are business-to-business. The financial industry and businesses dealing in commodities could potentially be excluded from the scope.

Second, the proposal suggests that only large businesses over a certain global revenue threshold (potentially €750 million, US $834 million) would be impacted. That same threshold currently applies in country-by-country reporting requirements.

Amount A

The first category of the three in the proposal is Amount A. To determine Amount A, the proposal describes several sub-amounts that need to be calculated or defined. The Secretariat’s proposal identifies these as described in Table 1.

| Profit Margin | Z |

| Deemed Routine Profit Margin | X |

| Deemed Non-Routine Profits | Y=Z-X and Y=W+V |

| Deemed Non-Routine Profits Attributable to Markets | W |

| Deemed Non-Routine Profits Attributable to Other Factors | V |

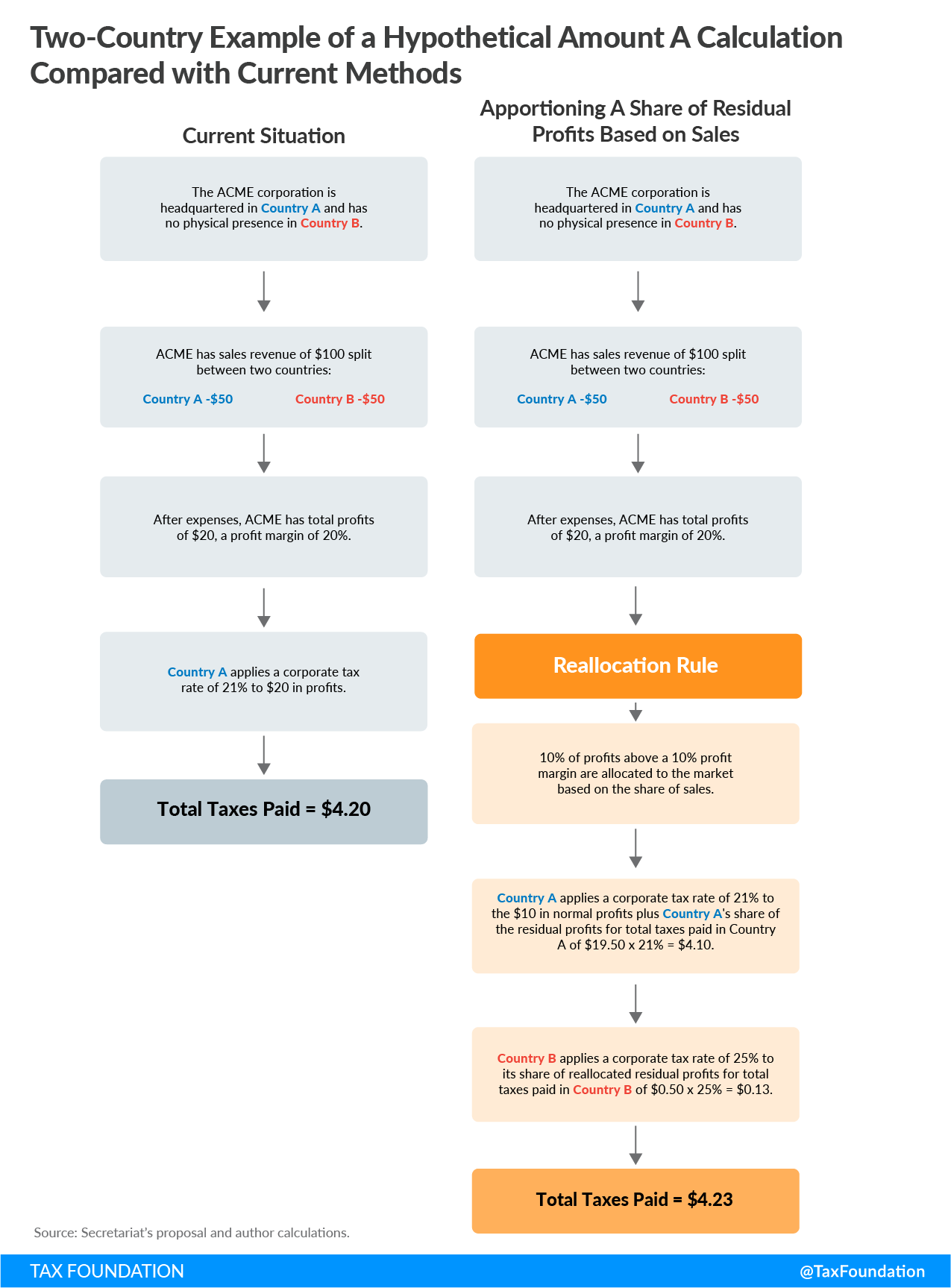

If, for example, the deemed routine profit margin (x) is 10 percent, and the share of deemed non-routine profits attributable to markets (w) is also 10 percent, then a company with a 20 percent profit margin (z) could expect that 10 percent of the 10 percent in deemed non-routine profits could be taxed in market jurisdictions. A similar example is laid out in Figure 1.

The country where ACME business has physical presence (Country A) would still be entitled to tax most of ACME’s profits, but a small share of its profits would be allocated to Country B.

The two-country example is instructive, but it is not as complex as things will get. As taxing rights are reallocated to markets, there will be circumstances where businesses will need to file for foreign tax credits to avoid double taxation. The proposal brings up such a scenario in an illustration for Amount A. A mechanism to ensure that double taxation does not occur would need to be agreed to, but the coordination of new taxing rights vs. old taxing rights will be complicated.

Another piece to this puzzle is the proposal’s recommendation that only markets where a business has a “sustained and significant involvement in the economy” would gain the new right to tax. Defining that term could help businesses to know when they will face taxes in jurisdictions, but it could also create incentives for some businesses to avoid entering new markets because of the risk of higher tax compliance costs.

Amount B

The second category in the Secretariat’s proposal on Pillar 1 is Amount B. This would give countries a fixed taxable return when it comes to marketing or distribution activities. Many companies sell into markets via subsidiaries that simply market or distribute the products that were designed and made elsewhere. In some circumstances, countries have argued that more taxable profits should be attributed to marketing and distribution activities. This can be especially true for developing countries that may not have the tax administration capacity to challenge the reported taxable profits that companies report in their jurisdictions.

The goal of Amount B is to simplify things so that countries will know what profit margin they should attribute to marketing and distribution functions. If the OECD says that a distributor’s taxable profit margin should be a certain amount, then the tax authority in that jurisdiction would simply be able to tax that amount (although Amount C could change that, see below).

The challenge with defining a fixed return under Amount B is that different industries in different countries are in different economic situations and a one-size-fits-all approach would not reflect those differences. The OECD admits there are a variety of approaches that could be used to reflect local or industrial differences. The proposal suggests that while there could be one fixed percentage worldwide, that percentage could also vary by industry or region, or there could be another method that countries agree to.

Regardless, the document makes clear that Amount B would be a “baseline” approach for simplifying the taxation of marketing and distribution activities.

Amount C

The goal of Amount C is two-fold:

- Provide countries with flexibility to argue for a higher taxable profit than would be set under Amount B.

- Minimize the risk of one country claiming more than its share of taxable profits, which would result in double taxation.

The first piece would let countries that are unsatisfied with Amount B analyze the business activities in their jurisdiction (not strictly limited to marketing and distribution) and make the case that more of a company’s profits should be taxed in that jurisdiction. This could be done using current transfer pricing methods.

The second piece would ensure that disputes around Amount C could be resolved quickly and avoid any overlap between Amount A and Amount C.

If there is a country that taxes a company based on Amount A and that company also has marketing and distribution functions in that country, then the country could be entitled to tax both Amount A and Amount B. However, if the tax authority in that country decides that Amount B is not justified and argues that an additional Amount C should be taxed, there is potential that the combination of Amounts B and C would overlap with the share of non-routine profits under Amount A. In that case, the country would not only be claiming a larger share of the tax profits of the company, but the company would face double taxation.

There will need to be a complex coordination effort to prevent multiple instances of overlap between the combination of Amounts B and C with Amount A, otherwise double taxation would occur.

Conclusion

The simple math of coordinating Amounts A, B, and C could become an international tax nightmare for businesses if they face one or multiple jurisdictions that are unwilling to stick within the bounds of the formulas.

Businesses facing new tax payments in jurisdictions may choose to change their strategy to avoid having to file taxes in too many jurisdictions. Behavioral changes can impact investment decisions, which would then impact economic growth. The OECD’s impact assessment will be a necessary element to answering these questions.

In the big picture, the proposal means that there will be countries that lose tax revenues and others that gain. The politics are complicated because many countries seem to have already chosen their preferred method of claiming taxing rights over digital firms in the form of digital services taxes (DSTs). If there is double taxation due to DSTs or because a country is unwilling to conform to the structure of the Secretariat’s proposal, the impact would be a net negative for many businesses.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe