Key Findings

- After the recessions in 2001 and 2007–2009, Minnesota’s job growth has trailed the national average, suggesting Minnesota’s economy may not be as strong as it once was.

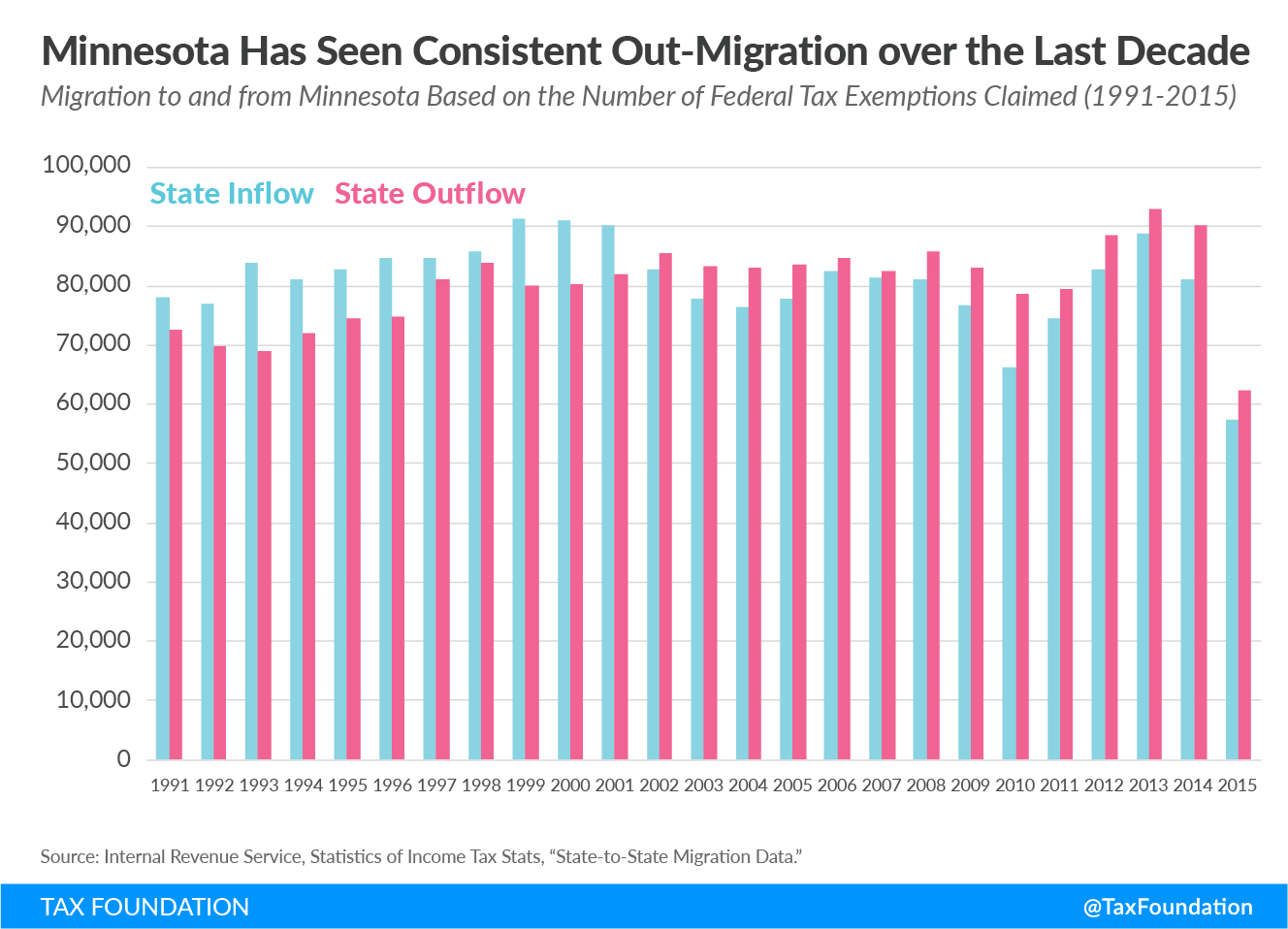

- Since the early 2000s, Minnesota has seen more than 76,000 people leave the state on net, with net out-migration occurring every year since 2002.

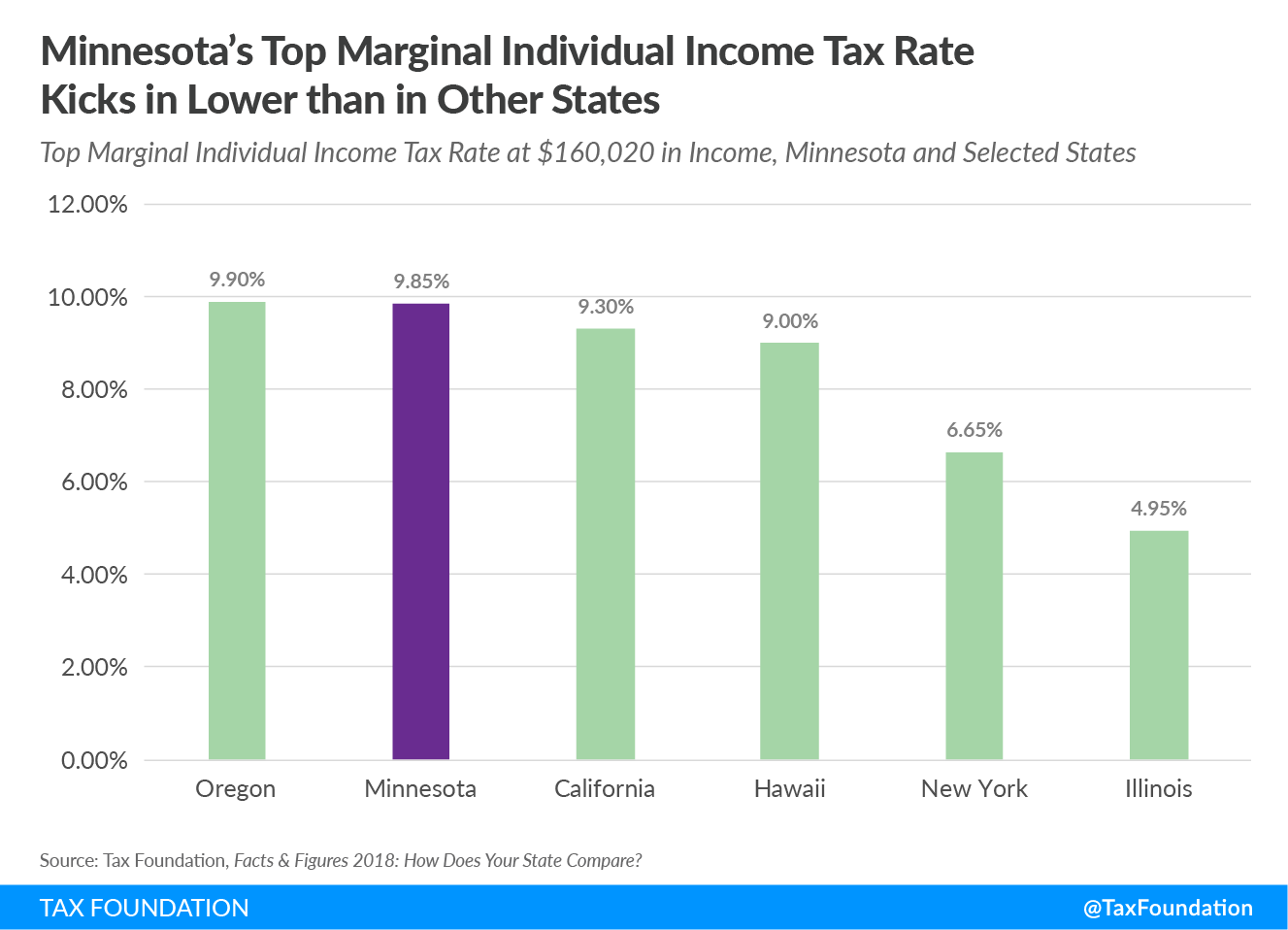

- Minnesota has the fourth highest top marginal individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rate in the country at 9.85 percent.

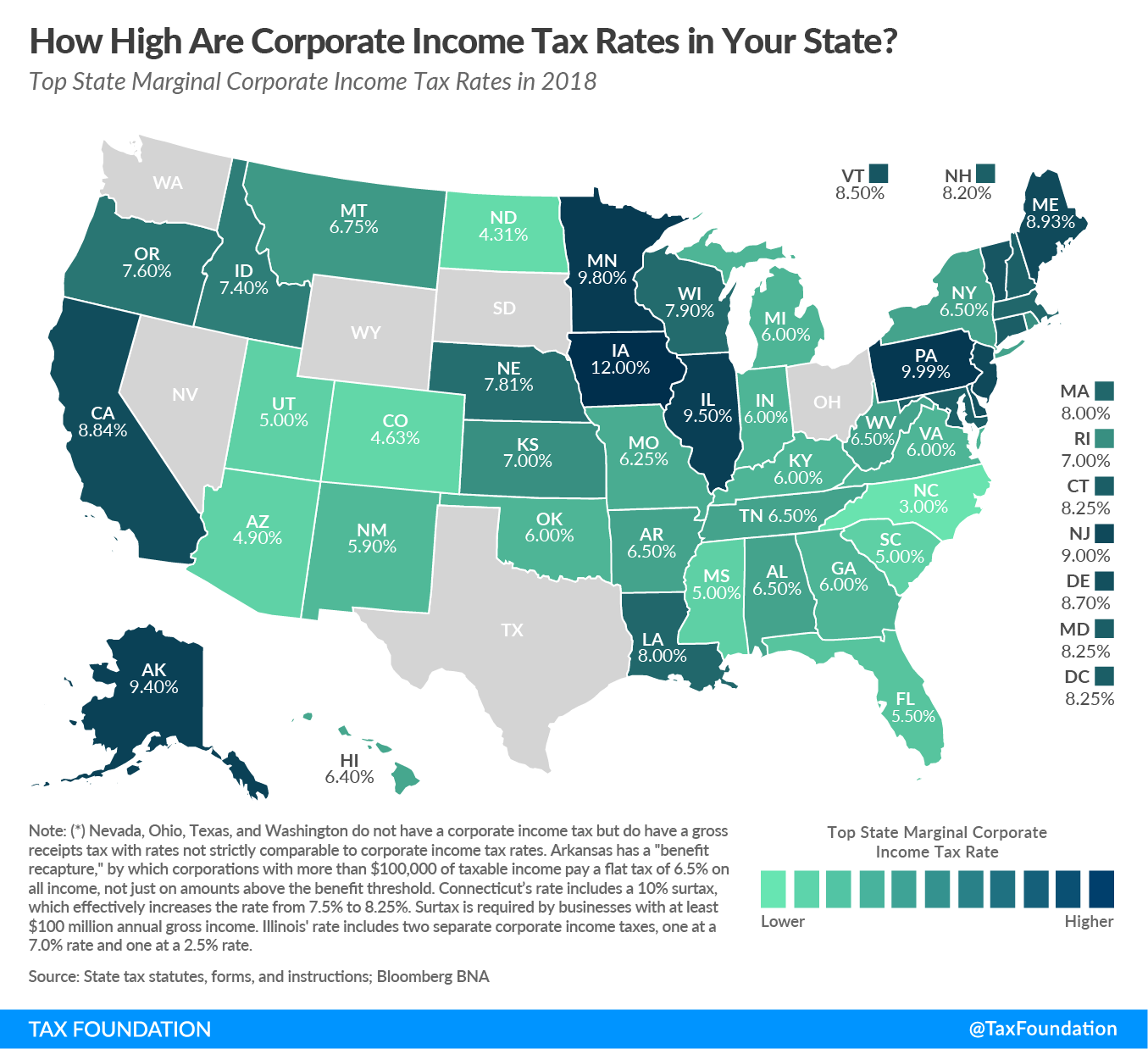

- Minnesota imposes the third highest corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate in the country at 9.8 percent, behind only Iowa and Pennsylvania’s (12 and 9.99 percent rates, respectively).

- Minnesota’s corporate income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. revenue has varied by as much as 42 percent year-over-year, making it difficult to properly budget when revenues are unpredictable.

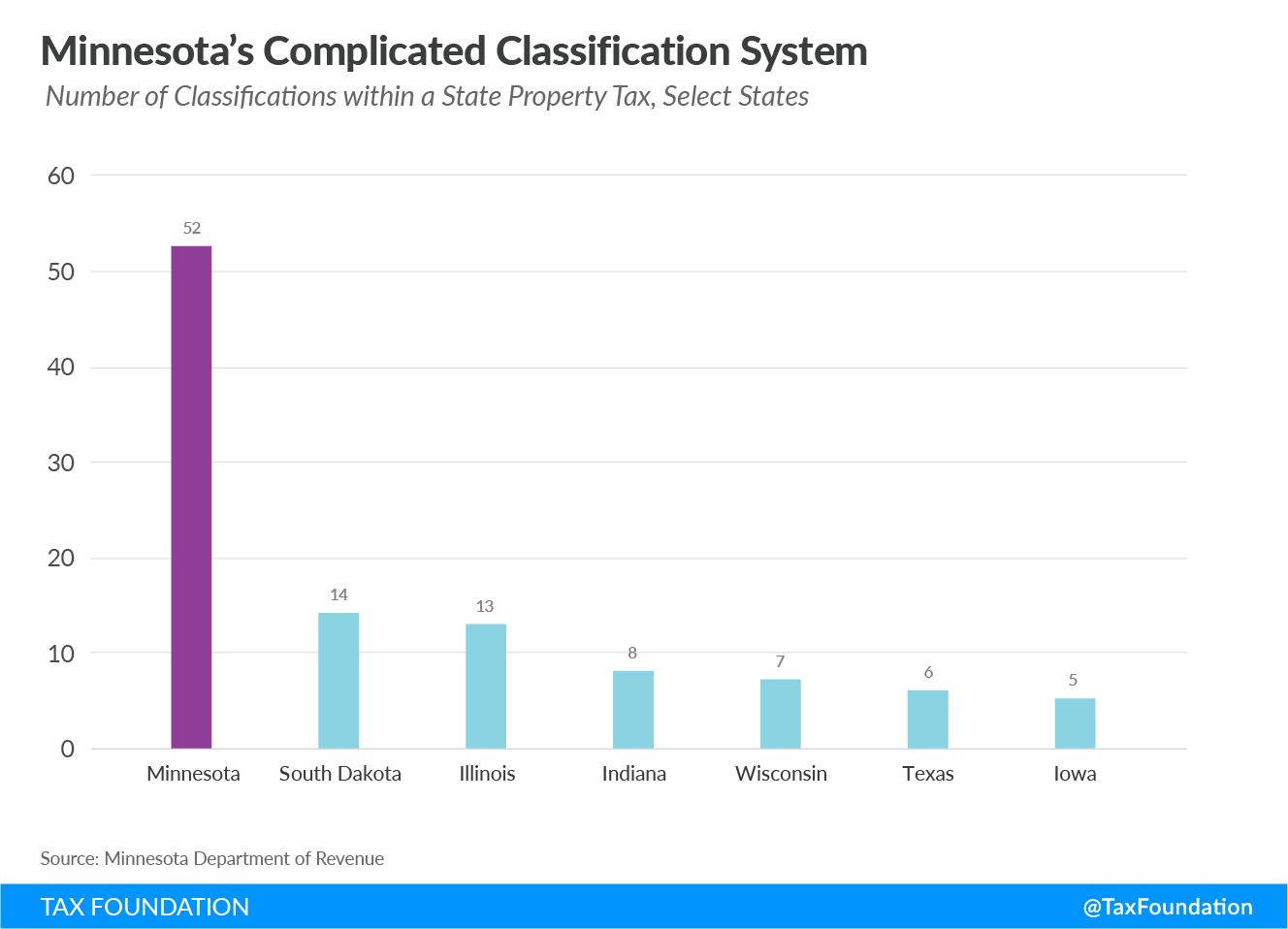

- On average, states have six classifications for their property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. structure. Minnesota is an extreme outlier with 52 property tax classifications, resulting in immense complexity. South Dakota has the second most nationally with 14.

- Minnesota legislators have yet to act to bring Minnesota up to date with new federal tax law provisions, which will create headaches if put off much longer. Without a conformity bill, Minnesota taxpayers can’t rely on consistent definitions between their state and federal income tax returns, and businesses will essentially be forced to keep two sets of books.

Introduction

Historically, Minnesota has boasted a strong economy and stacked up well against its neighboring states in many growth measures. However, some of those have recently begun to shift, signaling that the state’s economy may not be recovering or growing as quickly as previously.

In recent years, per capita income in Minnesota has risen above the U.S. average, as well as that of similar states.[1] Unemployment in the state has also been lower than the U.S. average.[2] Minnesota has historically created jobs faster than the national average during economic booms, and didn’t lose them as quickly during downturns.

However, since 2000, that trend has begun to reverse. After the recessions in 2001 and 2007–2009, Minnesota’s job growth has trailed the national average, suggesting Minnesota’s economy may not be as strong as it once was.[3] New trends in migration cut against the state as well. To stay competitive on both a regional and national scale, Minnesota needs to consider whether its tax code is working for or against it when it comes to attracting and retaining business.

Minnesota’s New Out-Migration Problem

Throughout the 1990s, Minnesota consistently saw an inflow of people moving to the state. Since the early 2000s, however, Minnesota has seen more than 76,000 people leave the state on net, with net out-migration occurring every year since 2002.[4] The state’s high taxes are likely a factor in this trend, and consistent out-migration is likely to harm the state’s economy. With fewer taxpayers in the state, the state’s tax base shrinks, meaning that eventually the state will need to increase its tax rates to generate the same amount of revenue.

The State’s Tax Code is Impeding Growth

Minnesota ranks 43th in the Tax Foundation’s State Business Tax Climate Index, largely due to the state’s high marginal tax rates and burdensome tax structure. The state levies the third highest corporate income tax and the fourth highest top individual income tax rate in the country. The top individual income tax rate is the highest in the region, and the corporate income tax rate is higher than nearly every other neighboring state, with Iowa the only exception. Iowa, however, has adopted legislation that will ultimately reduce the state’s corporate income tax rate and also currently offers a large deduction for federal taxes paid.

Minnesota also has a needlessly burdensome property tax system, with a dizzying latticework of classes of property and a uniquely harmful statewide business property tax. These problems discourage investment and inhibit economic growth in the state.

Tax rates contribute to a state’s competitiveness, but other factors matter as well. Tax bases and tax structures play an essential role in determining the strength of a state’s tax climate. For instance, Minnesota’s property and individual income taxes are not competitive with those of Minnesota’s peer states. All of Minnesota’s peer states have better structured tax codes, hurting Minnesota’s ability to compete with them for investment, jobs, and residents.

For example, Indiana ranks in the top 10 states in the Index, and still uses all major tax instruments, demonstrating that states can levy every major tax type and still have a well-structured tax code. As Minnesota faces new challenges, it needs tax reform in the key areas of individual income taxes, corporate income taxes, and property taxes.

Individual Income Tax

Forty-one states tax wage income, with the majority using graduated-rate structures. Minnesota is one of those states but stands out for two reasons: its high top marginal rate and its low rate threshold. Among the states that levy income taxes on wages and salaries, Minnesota has the fourth highest top marginal individual income tax rate in the country at 9.85 percent. In comparison with other states, the top rate kicks in at the relatively low income level of $160,020 for single filers, and the second highest rate of 7.85 percent kicks in at $85,060. For contrast, states typically thought of as “high-tax states” like New York and California don’t apply their top rate until above $1 million in income.[5]

Income tax collections per capita in Minnesota have also exceeded the national average since 1977. In 2016, Minnesota collected $1,943 per capita in income taxes, the fifth highest in the country. The state also relies more heavily on individual income taxes than the U.S. average (23.5 percent), and therefore, less heavily on sales and property taxes—23.5 and 31.1 percent, respectively. Minnesota obtained the largest share of state and local combined collections in 2015 from individual income taxes (31.8 percent of total), followed by property taxes (25.8 percent) and sales taxes (17.4 percent).[6]

This is problematic for Minnesota residents and businesses, as income is quickly subject to very high tax rates, disincentivizing work and investment in the state. Income taxes tend to be more harmful to economic growth than consumption taxes and property taxes, affecting labor participation, saving, and investment.[7]

Corporate Income Tax

Minnesota’s flawed corporate income tax code is holding the state back as well. The state imposes the third highest corporate income tax rate in the country at 9.8 percent, behind only Iowa and Pennsylvania (12 and 9.99 percent rates, respectively). Minnesota also levies an Alternative Minimum Tax.[8]

Lowering the corporate income tax rate would be a step in the right direction for the state to enhance its competitiveness. Corporate income taxes act as a penalty on profits and a double-tax on investment, but are also known to especially limit entrepreneurship by hurting start-up businesses.[9] One recent study found that for every percentage point increase in the corporate tax rate, start-up employment declines by 3.7 percent.

As it stands, Minnesota’s corporate income tax rate is not regionally competitive with states like North Dakota, South Dakota, or Wisconsin. Iowa is the only surrounding state with a higher rate, but Iowa offers a deduction for federal taxes paid and is currently in the process of lowering its corporate income tax rate.[10]

Corporate income taxes are largely passed forward to consumers, workers, and shareholders, meaning that everyday Minnesotans–not corporations–pay a large portion the tax. Taxes paid by businesses are ultimately borne by individuals, whether in the form of higher prices, lower wages, or smaller returns on investment.

Additionally, corporate income taxes are unstable revenue sources for states, and being heavily reliant on them can make budgeting more difficult. Minnesota’s corporate income tax revenue has varied by as much as 42 percent year-over-year, making it difficult to properly budget when revenues are unpredictable.[11]

Property Tax

Minnesota also imposes a needlessly burdensome and complex property tax system, with many rate classes and a unique statewide business property tax.

Rates in the state vary widely by county. Between 2010 and 2014, the average residential effective property tax rate in Minnesota was 1.14 percent, though county-specific values vary. The highest effective property tax rate occurred in Ramsey County at 1.32 percent, followed closely by 1.29 percent in Hennepin County. The lowest was in Cook County at 0.5 percent.[12]

States generally vary their property tax rates by the type of property, such as residential, industrial, or agricultural. On average, states have six classifications for their property tax structure. Minnesota is an extreme outlier with 52 property tax classifications, resulting in immense complexity. South Dakota has the second most nationally with 14.[13]

The state’s businesses are also burdened with a special state property tax levied on commercial, industrial, and recreational property. Commercial and industrial properties pay 95 percent of the tax, while cabins pay the remaining 5 percent. The tax mandates an annual increase in the amount of taxes collected and has grown from $592 million in 2002 to $863 million in 2016, a 46 percent increase in 14 years. [14]

Complexity Looming if Minnesota Doesn’t Act

One major conversation being had around the country this year is how best to conform to the new changes installed in federal law by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Conforming to the federal tax code is important for a number of reasons, including reducing compliance costs for taxpayers. States rely on the federal tax code to varying degrees to provide definitions, income starting points, exclusions, and deductions. Minnesota’s tax code relies on the federal code more heavily than other states because the starting point for the state’s tax return is federal taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , meaning taxable income in the state includes federal exemptions and deductions.[15]

Minnesota legislators have yet to act to bring Minnesota up to date with these new provisions, which will create headaches if put off much longer. Without a conformity bill, Minnesota taxpayers can’t rely on consistent definitions between their state and federal income tax returns, and businesses will essentially be forced to keep two sets of books. Complying with the tax code is already complicated—Minnesota shouldn’t make it more difficult for taxpayers in the state by refusing to conform to even the most basic changes to the federal tax code.[16]

Conclusion

Minnesota should consider whether businesses have located in the state because of its tax code or in spite of it. Its high marginal rates and complexity do not incentivize investment or business in the state. Fortunately, the conversation around conformity provides an opportunity for Minnesota to tackle some of these issues. Good tax policy includes broad bases and low rates, and Minnesota now has the chance to tackle both areas. The federal government broadened the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. for states, and Minnesota has an opportunity to use the revenue from base broadening to lower its rates to be more competitive regionally and nationally.

Notes

[1] Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Data, “Annual State Personal Income and Employment.”

[2] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Local Area Unemployment Statistics.”

[3] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics.

[4] Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Tax Stats, “State-to-State Migration Data.”

[5] Morgan Scarboro, “State Individual Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2018,” Tax Foundation, March 5, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-individual-income-tax-rates-brackets-2018/.

[6] U.S. Census Bureau; Tax Foundation calculations.

[7] William McBride, “What Is the Evidence on Taxes and Growth?” Tax Foundation, Dec. 18, 2012, https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/sr207.pdf.

[8] Morgan Scarboro, “State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2018,” Tax Foundation, February 2018, /wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Tax-Foundation-FF5711.pdf.

[9] Scott Drenkard, “New Federal Reserve Paper: State Corporate Taxes Hurt Entrepreneurship,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 16, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/new-federal-reserve-paper-state-corporate-taxes-hurt-entrepreneurship/.

[10] Jared Walczak, “What’s in the Iowa Tax Reform Package,” Tax Foundation. May 9, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/whats-iowa-tax-reform-package/.

[11] U.S. Census Bureau, “State & Local Government Finance.”

[12] U.S. Census Bureau, “American Community Survey (ACS).”

[13] Minnesota Department of Revenue.

[14] Minnesota Department of Revenue, “Property Tax Statistics;” The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence, “50-State Property Tax Comparison Study.”

[15] Jared Walczak, “Tax Reform Moves to the States: State Revenue Implications and Reform Opportunities Following Federal Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 31, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-conformity-federal-tax-reform/.

[16] Morgan Scarboro, “Governor Dayton Vetoes Minnesota’s Conformity Bill,” Tax Foundation, May 17, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/governor-dayton-vetoes-minnesotas-conformity-bill/.

Share this article