Key Findings

- Although there is no empirical standard for what constitutes a “fair share” of the taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. burden, tax fairness is often used by leading international organizations, such as the European Commission, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as the Tax Justice Network, to justify higher taxes on businesses and corporations.

- Recent studies show that businesses and corporations contribute significantly to government coffers through the taxes they are legally liable to pay and the taxes they are required to collect and remit on behalf of others.

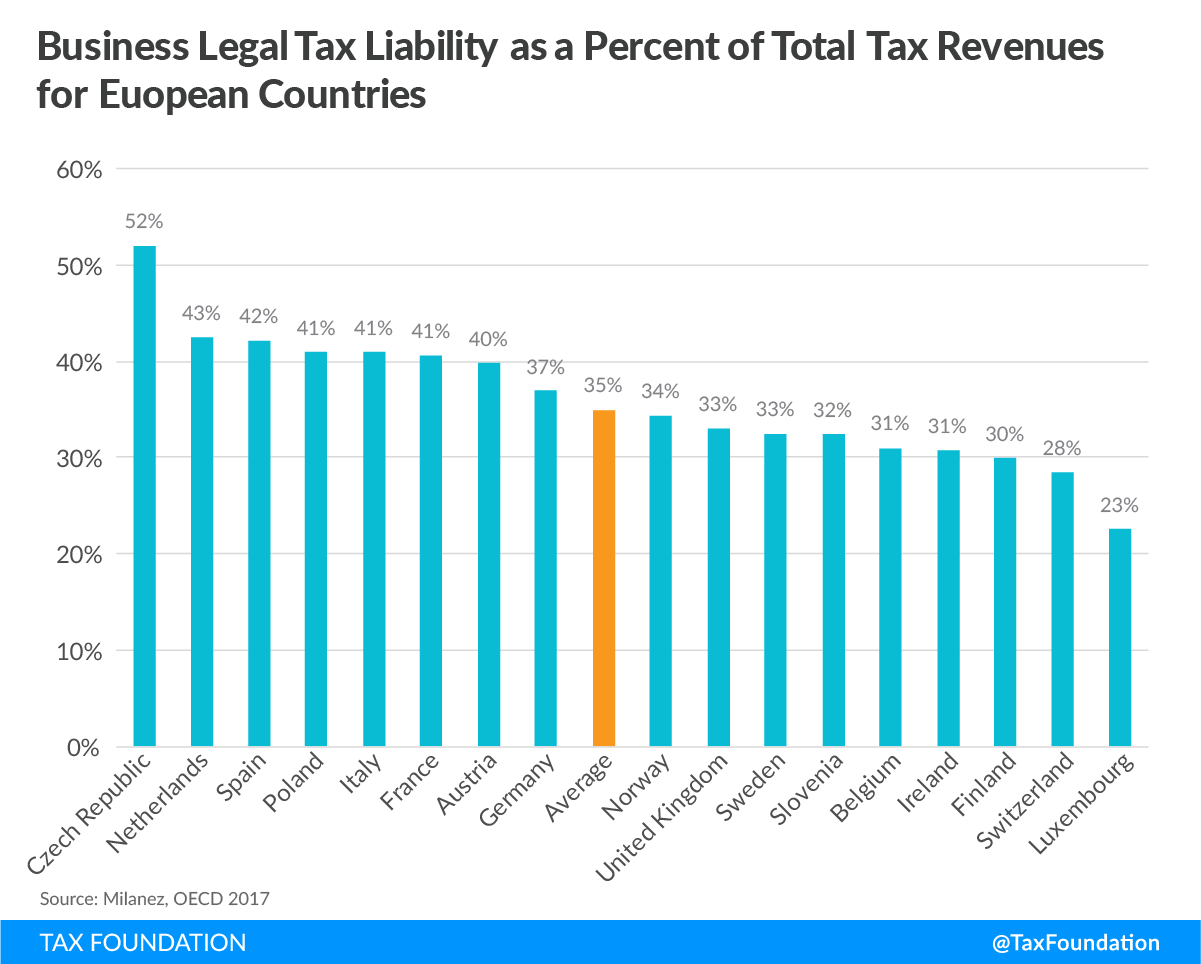

- A recent study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that corporations and businesses pay an average of 33.5 percent of the total taxes collected by 24 leading OECD countries.

- The Czech Republic has the most “business dependent” tax system, with businesses contributing 52 percent of all collections. Six countries receive more than 40 percent of their total revenues from business—Austria, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain.

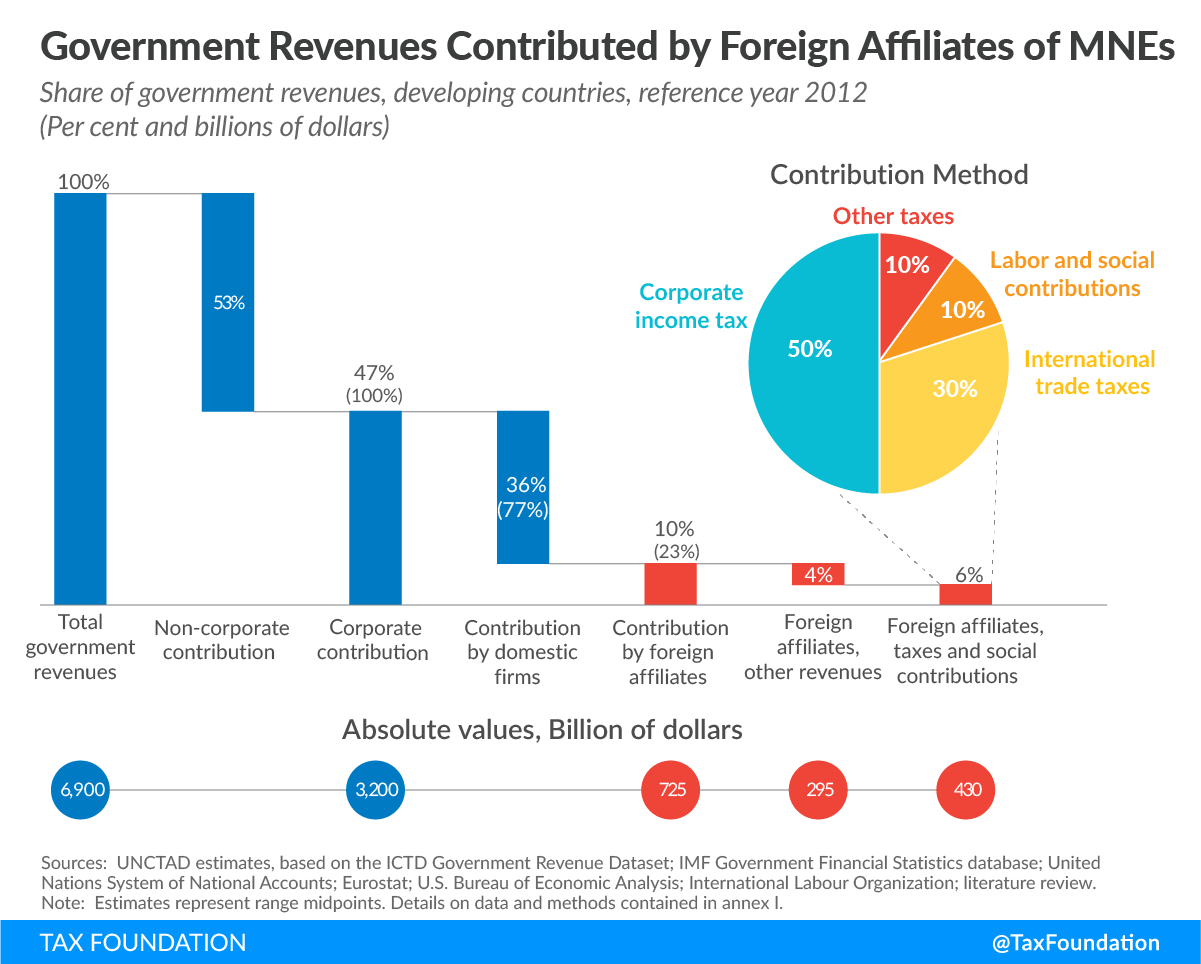

- Another study by international economists found that corporations and multinational enterprises paid a total of $3.2 trillion in taxes to developing nations, nearly half of their total tax collections.

- Policymakers must be careful about trying to raise the tax burden on businesses because the ultimate economic burden of these tax hikes will ultimately fall on workers through lower wages, shareholders through lower returns, or consumers through higher prices or fewer goods.

Introduction

“Tax fairness” has been a frequent theme in the international debate over corporate and business taxation in recent years. Officials at the European Commission justified[1] their recent call for a new 5 percent tax on the profits of a select group of digital companies based on the claim that they were not paying their fair share of taxes. Officials at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) often cite tax fairness as the motivation for their project to stop base erosion and profit-shifting (the so-called BEPS project). And, various non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as Tax Justice Network, make the claim that the inability of developing countries to provide basic services is due to corporations not paying their fair share of taxes.

The problem with such claims is that there is no empirical standard for what constitutes a “fair share” of the tax burden. How much is a “fair share” is ultimately subjective and may differ based on the values in each country. However, recent studies show that businesses and corporations contribute significantly more tax revenues to government coffers than the popular rhetoric would suggest.

For example, a recent study by an economist at the OECD found that businesses – including corporations and so-called pass-through firms – pay an average of 33 percent of all taxes collected by the leading industrialized nations. The Czech Republic has the most “business dependent” tax system, with businesses contributing 52 percent of all collections. Six countries receive more than 40 percent of their total revenues from business—Austria, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain.

Another study by economists at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) found that domestic and foreign corporations paid $3.2 trillion in total taxes to developing nations, nearly 50 percent of their total collections. Of this amount, the affiliates of foreign multinationals contributed $725 billion in taxes to developing countries, 11 percent of their total collections.

In addition to these sizable direct payments, businesses also collect and remit a variety of taxes on behalf of others, such as sales and value-added taxes and withheld income taxes, streamlining tax collections for governments. The OECD study determined that business remittances contribute an additional 45 percent of tax revenues for the average developed country.

These studies suggest that if it were not for the taxes that businesses either pay directly or are legally liable to collect and remit, most governments would be unable to pay for even the most basic public services. And because businesses are so directly accountable in the process of paying taxes and collecting taxes, it can actually reduce the amount of tax avoidance that might otherwise occur if government tax collectors were to assume those duties. As a consequence, businesses bear a large share of the compliance cost of the tax system.

While businesses may be the primary tax collector for government, lawmakers should not lose sight of who actually bears the economic burden of taxes and the impact of taxes on economic growth. Ultimately, the economic burden of taxes falls either on workers, consumers, or the business owners, so the notion that “businesses” must shoulder a greater share of the tax burden means that one or more of those stakeholders will bear those costs with a lower standard of living.

Categories of Business Tax Payments in OECD Countries

When most people think of business taxes, they tend to think of the corporate income tax (CIT) or the income taxes paid by non-incorporated businesses, such as sole proprietorships or LLCs. But businesses have numerous other taxes that they are legally liable to pay and a host of taxes that they are legally liable to remit on behalf of others.

In a recent OECD study, “Legal tax liability, legal remittance responsibility, and tax incidenceTax incidence is a measure of who bears the legal or economic burden of a tax. Legal incidence identifies who is responsible for paying a tax while economic incidence identifies who bears the cost of tax—in the form of higher prices for consumers, lower wages for workers, or lower returns for shareholders. ,” [2] economist Anna Milanez uses tax collection data to calculate the relative amount of taxes that businesses either pay directly or remit to governments in 24 OECD countries. Because of the different ways in which businesses are organized in each country, Milanez aggregated the data for both corporations and so-called pass-through businesses to get a comparable picture of business involvement across tax systems.

Milanez first sets out to categorize the different revenue streams that governments rely on. As Table 1 below illustrates, she separates revenues into three categories: legal tax liability of business; legal remittance responsibility of business; and, non-business remittance.

Legal Tax Liability of Business. The taxes for which businesses are legally liable include the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. , the income taxes owed by unincorporated businesses, employer-paid social security taxes, taxes on payroll, excise taxes, and property taxes. As Milanez notes, while social security contributions are applied to both an employer’s payroll and an employee’s wages, the reason they are included in this category is that only the employer-side is the legal responsibility of the business. And, here we are focused only on the legal incidence of the tax because economists generally agree that workers bear the full economic incidence of both sides of the social security tax.

Legal Remittance Responsibility of Business. These direct liabilities are different from the taxes that businesses are legally required to collect and remit on behalf of others. As we can see on Table 1, these remittances include value-added taxes paid to retailers by customers, withholding taxes on the income earned by employees or the capital income earned by shareholders, and the employee’s share of social security taxes. As Milanez notes, “The design of withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount the employee requests. taxes is aimed at ensuring that taxes are paid in a timely manner for government funding obligations.”

Further, Milanez emphasizes, “While businesses are not legally liable for withholding taxes, they do hold the legal remittance responsibility in many OECD countries.” Indeed, this makes the collection of income taxes from millions of taxpayers easier for government agencies and ensures that the amount withheld is accurate with a minimal amount of avoidance.

Non-Business Remittances. The remainder of revenues collected by governments, “non-business remittances,” are largely comprised of personal income taxes paid directly by taxpayers, the withholding taxes governments pay on behalf of civil servants, property taxes paid by households, and estate and gift taxes. As we will see below, in some countries these taxes comprise a very small percentage of overall tax collections.

| Sources: OECD Revenue Statistics; classification by businesses’ role in the tax system by author | |||

| Revenue Statistics Tax Category | Legal Tax Liability of Business | Legal Remittance Responsibility of Business | Non-business Remittance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxes on income, profits and capital gains | Non-corporate business income subject to personal income tax; corporate income tax | Withholding taxes on labour and capital income | PIT paid directly by individuals; public-sector withholding taxes on labour income |

| Social security contributions | Employer SSCs; self-employed or non-employed SSCs | Employee SSCs | Public-sector SSCs |

| Taxes on payroll and workforce | Taxes on payroll and workforce | ||

| Taxes on property | Recurrent taxes on immovable property; paid by other | Recurrent taxes on immovable property; paid by households; estate, inheritance and gift taxes | |

| Taxes on goods and services | Excise taxes; profits of fiscal monopolies; recurrent taxes on motor vehicles; paid by others | Value-added taxes; sales taxes; insurance taxes | Recurrent taxes on motor vehicles; paid by households |

| Other taxes | Other taxes paid solely by business | “Other” other taxes | |

| Unallocated | Unallocable amounts in each Revenue Statistics category (e.g. RS 1300); recurrent taxes on net wealth; taxes on financial and capital transactions; non-recurrent taxes on property; customs and import duties; taxes on exports; taxes on investment goods; taxes on specific services; recurrent taxes on use of goods and performance of activities other than motor vehicles. | ||

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeMeasuring the Amount of Taxes Paid by Business in OECD Countries

Using OECD tax revenue data supplemented by survey information from countries, Milanez compiled the different revenue streams into the three main categories shown in Table 2: non-business tax collections, business legal tax liability, and taxes remitted by business. Here we will focus on the legal tax liability of business because that is the issue that tends to be most in dispute.

Countries are quite different in how much they rely on business tax payments, but the typical OECD country receives 33.5 percent of its tax revenues from businesses. The Czech Republic is the most “business-reliant” country with businesses paying 52 percent of its total tax collections. Portugal could be considered the least business-reliant, with 19.4 percent of its total collections paid by businesses. Five countries—Austria, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain—each receive more than 40 percent of their total tax collections from direct payments by business.[3]

| Country | Non-Business Tax Collections | Business Legal Tax Liability | Taxes Remitted by Business |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Milanez, OECD 2017 | |||

| Australia | 19% | 31.9% | 48.8% |

| Austria | 8% | 40.6% | 51.6% |

| Belgium | 19% | 32.4% | 48.3% |

| Canada | 28% | 28.5% | 44.0% |

| Chile | 13% | 31.0% | 56.2% |

| Czech Republic | 15% | 52.0% | 32.7% |

| Finland | 26% | 30.7% | 42.9% |

| France | 35% | 40.9% | 24.5% |

| Germany | 9% | 36.9% | 54.6% |

| Ireland | 15% | 31.0% | 54.5% |

| Italy | 21% | 39.8% | 39.6% |

| Luxembourg | 40% | 22.5% | 37.6% |

| Mexico | 28% | 28.1% | 43.7% |

| Netherlands | 5% | 42.2% | 52.6% |

| New Zealand | 12% | 25.0% | 63.0% |

| Norway | 37% | 34.4% | 28.9% |

| Poland | 19% | 40.9% | 40.3% |

| Portugal | 40% | 19.4% | 40.4% |

| Slovenia | 24% | 32.5% | 43.8% |

| Spain | 14% | 42.5% | 43.3% |

| Sweden | 14% | 33.0% | 53.4% |

| Switzerland | 47% | 28.4% | 24.6% |

| United Kingdom | 17% | 29.9% | 53.5% |

| United States | 7% | 28.9% | 64.2% |

| Average | 21.2% | 33.5% | 45.3% |

Income taxes from corporations and pass-through businesses comprise an average of 11.5 percent of all tax collections for OECD countries. Slovenia collects the least amount at 4.5 percent of total collections, while Chile collects the most at 21.3 percent of total revenues.

Excise taxes are typically considered a tax on individual consumers, but OECD countries collect an average of 7.4 percent of their total tax revenues from excise taxes paid by businesses on input purchases. The United States collects the least amount of excises on business inputs at 3.7 percent of revenues, while Poland and Slovenia collect the most in excise taxes at 12.5 percent and 12.0 percent of total revenues respectively.

In addition to the corporate income tax, excises, and a small amount of property taxes, businesses are being asked to shoulder a growing share of the burden for social security contributions in many countries. Milanez reports that while these contributions are generally split between the employee and the employer, “On average across OECD countries, employer social security contributions made up 53% of all social security contributions and 9.5% of the total tax mix in 2014.”[4] For the 24 countries surveyed for Milanez’s report, social security payments by businesses averaged 11.9 percent of total revenues, slightly more than business income tax collections.[5]

Moreover, Milanez found that in 2014, social security contributions were the largest source of tax revenue in nine OECD countries—Austria, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, and Spain. Not surprisingly, a number of these countries lead the list of those most dependent upon business tax payments.

Figure 1.

U.S. is Most Reliant on Tax Remittances from Business

As Table 2 shows, businesses collect and remit an average of 45 percent of the total tax revenues in OECD countries. Interestingly, the country that relies most on tax remittances by business is the United States at 64.2 percent of all tax collections. In large measure, this is due to the important role that U.S. businesses play in collecting withholding taxes from employees for their income and Social Security taxes. New Zealand is another country in which businesses remit more than 60 percent of total tax collections, in this case 63 percent of all collections.

In seven countries, businesses remit more than 50 percent of all tax collections—Austria, Chile, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Meanwhile, France and Switzerland could be considered the least reliant on business remittances, each collecting roughly 25 percent of all tax revenues from this source.

While each country may have a different mix of business tax payments and tax remittances, it is clear from this data that OECD public finance systems are heavily reliant on businesses as the primary taxpayer and tax collector.

Business Tax Payments in Developing Countries

In 2015, economists at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) conducted an in-depth analysis of corporate tax contributions to developing nations and published the findings in the “World Investment Report 2015.”[6] Unlike the OECD study, which measured the total tax contributions of all businesses, UNCTAD economists set out to estimate the fiscal contribution of corporations and multinational enterprises (MNEs) to 120 developing countries to better understand to what extent tax avoidance is impacting the revenues of those nations. UNCTAD’s methodology differs slightly from the OECD study – for example, they didn’t consider the amount of legal remittances of things like employee withholding taxes – but the general findings are similar to OECD’s.

Overall, they found that “developing countries rely more on corporates for government revenue collection than do developed countries.” This is especially true “in developing countries with large informal economies” and those that tend to have less sophisticated tax collection systems. In such countries, “Corporate contributions to overall revenues and to income taxes are more important due to the low levels of collection of other revenue and tax categories.”[7]

UNCTAD estimated that in 2012, developing countries had total tax collections of $6.9 trillion. As is illustrated in the report’s Figure V.6., below, corporate contributions comprised 47 percent of that total. These contributions included corporate income taxes, property taxes, the employer share of “social contributions” taxes, severance taxes, and taxes on international trade.

In absolute value, the fiscal contribution of corporations to developing countries totaled $3.2 trillion in 2012, the majority of which was generated by domestic firms. The affiliates of foreign multinationals paid an estimated $725 billion in taxes to developing countries, an amount equal to 11 percent of total revenues. The majority of these collections ($430 billion) were generated by taxes on corporate income, labor, and international trade. The remainder ($295 billion) came from other sources, such as severance taxes.

UNCTAD found that the fiscal contributions of the foreign affiliates of MNEs varied by region. While these firms contributed roughly 11 percent overall to the treasuries of developing nations, they contributed 14 percent to African countries, 11 percent to Asian countries, and 9 percent to Latin American and Caribbean countries.

While these contributions may seem small relative to the overall revenues of these countries, they are considerable relative to the profits of MNE affiliates. For example, when UNCTAD compared the total tax contributions of MNE affiliates to their commercial profits, the “effective fiscal burden” totaled 50 percent of affiliate profits for developing nations overall. In Africa, the fiscal burden was 54 percent of affiliate profits; in Asia it was 49 percent; and in Latin America and the Caribbean the fiscal burden was 53 percent (p.187 of the report).

Figure 2.

The Economic Incidence of Taxes on Business

It has long been recognized by economists that while businesses bear a legal responsibility to pay taxes directly and remit other taxes on behalf of others, the economic burden of those taxes tends to fall on workers through lower wages, shareholders and owners through lower returns on capital investments, or consumers through higher prices. Thus, the notion that businesses or corporations should pay their “fair share” of taxes is a rhetorical device, not an actual one. Any attempt to increase the tax burden on corporations will inevitably harm workers, shareholders, or customers. The amount of the harm will simply depend upon the type of tax and the economic circumstances in which the tax is levied.

Milanez’s OECD study contains a third chapter summarizing the economic literature on the incidence of various taxes, not just the corporate income tax, which has typically received the most attention from economists, but also taxes on labor income and value-added taxes.

Economists have studied the economic incidence of the corporate income tax since the 1960s. While many of the earliest studies tended to conclude that owners of capital bore the lion’s share of the cost of the corporate income tax, more recent studies are finding that more of the burden is falling on labor, although the share will depend on various factors and methods of measurement.

For example, studies comparing the cross-country differences in corporate tax rates on the wages of workers have typically found a negative relationship between higher corporate tax rates and lower worker wages. These studies estimate that between 45 percent and 400 percent of the burden of the corporate income tax will fall on workers.[8]

How could a tax fall 400 percent on workers? First, the impact of the corporate income tax on the economy is much larger than the actual dollar amount of taxes collected. Second, the overall size of the wage base is many times the amount of the corporate taxes collected, so a small dollar increase in the corporate tax can have a relatively outsized effect on wages. For example, the Congressional Budget Office reports that corporate income taxes totaled $297 billion in 2017. By contrast, wages and salaries in the U.S. totaled $8.3 trillion—27 times larger than corporate tax collections. So it is easy to see why the study found that for every $1 of corporate income taxes collected by a high tax rate, the overall amount of aggregate worker wages fell by $4, or 400 percent of the tax increase.[9]

Studies that compared the differences in corporate income tax rates among U.S. states found a similar range of effects. One study determined that 30 percent of the corporate tax fell on workers, while another found that the burden was more like 360 percent, due to the overall reduction in aggregate worker wages.

A third group of studies looked at the impact of the corporate income tax on wages in circumstances where workers and employers negotiate frequently about wages. A study of corporate tax changes on worker wages in Germany found that when corporate tax rates were reduced, workers enjoyed 40 percent of the benefits through higher wages. A similar study in the U.S. found that workers captured 54 percent of the benefits when corporate tax rates were lowered.[10]

Economists have generally found that taxes on labor income, such as social security and payroll taxes, tend to be borne by workers through lower wages. However, some studies have found that not all of such taxes are borne by workers; some of the burden can be shifted to employers and consumers, although the extent of this shifting is unclear.

Similarly, value-added taxes and retail taxes are generally thought to be entirely borne by consumers, although how much of the tax is passed on to consumers may depend upon the market power of the seller. Some studies have found that more than 100 percent of the tax can be passed on to consumers. One study of cigarette tax increases found that a $1 increase in the tax resulted in price increases of as much as $1.13.[11]

While the economic burden of these taxes may fall on workers or consumers, businesses do typically bear the compliance costs of collecting and remitting these taxes themselves. These costs are not insignificant and are not included in the overall economic impact of business taxes.

Conclusion

Credible studies by leading international institutions show that any claims that corporations are not paying their “fair share” of taxes are unfounded and unsupported by the facts. Indeed, in developed countries in the OECD, businesses pay an average of one-third of all taxes collected. In developing nations, corporations contribute nearly half of all taxes collected, with a sizable portion of that contributed by the affiliates of foreign multinationals.

It is fair to say, that without the taxes that businesses pay directly or remit on behalf of others, countries would not have the resources to pay for essential government services. Moreover, without businesses acting as tax collectors and bearing those compliance costs, government tax collection agencies would have to incur substantial costs and hire armies of official tax collectors to raise the same amount of revenues.

UNCTAD researchers issued a warning to global leaders who may want to raise taxes on multinational companies: “[A]ny policy action aimed at increasing fiscal contribution and reducing tax avoidance, including the policy actions resulting from the BEPS project, will also have to bear in mind the first and most important link: that of tax as a determinant of investment.”

In other words, taxes matter a lot to investment decisions. Therefore, global tax collectors must weigh the marginal benefit of extracting additional revenues from companies against the economic harm caused by the loss of investment, jobs, and economic growth that corporations make possible.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe[1] European Commission, “Fair Taxation of the Digital Economy,” March 21, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/business/company-tax/fair-taxation-digital-economy_en.

[2] Anna Milanez, “Legal tax liability, legal remittance responsibility and tax incidence: Three dimensions of business taxation” (OECD Taxation Working Papers No. 32), OECD Publishing, Paris, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/e7ced3ea-en

[3] Ibid., p. 32.

[4] Ibid., p. 22.

[5] Ibid., p. 32.

[6] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), “World Investment Report 2015: Reforming International Investment Governance,” Chapter V, “International Tax and Investment Policy Coherence,” http://unctad.org/en/PublicationChapters/wir2015ch5_en.pdf. See also UNCTAD, “Annex I, Establishing the baseline: estimating the fiscal contribution of multinational enterprises,” a technical background paper accompanying the “World Investment Report 2015,” Chapter V, “International Tax and Investment Policy Coherence,” http://unctad.org/en/PublicationChapters/wir2015ch5_Annex_I_en.pdf.

[7] Ibid., p. 183.

[8] Stephen J. Entin, “Labor Bears Much of the Cost of the Corporate Tax,” Tax Foundation Special Report No. 238, October 24, 2017, p. 9, https://taxfoundation.org/labor-bears-corporate-tax/.

[9] Cited in Entin: R. Alison Felix, “Passing the Burden: Corporate Tax Incidence in Open Economies” (Regional Research Working Paper RRWP 07-01, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City), October 2007, 21,

https://www.kansascityfed.org/QeLUe/Publicat/RegionalRWP/RRWP07-01.pdf

[10] Both studies are cited in Entin, p. 10.

[11] Milanez, p. 40.

Share this article