Chairmen Fonfara and Rojas and Members of the Committee:

I’m here before you today to testify on H.B. 7410, and to speak more broadly—but briefly, I promise—on the need for tax reform in Connecticut. There’s no question, I think, that Connecticut faces serious challenges. But if an outsider just took a glance at the statistics, that might come as a surprise.

This is an affluent state by any measure, but let’s just pick one: at $74,561, Connecticut has the highest per capita income of any state in the country. And at $7,220 per person, the state has the second-highest state and local taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. collections per capita in the country, behind only New York, and about 50 percent higher than the national average. Now, being an affluent state does mean less federal aid, but even then, Connecticut ranks 9th on revenue per capita—and doesn’t have many of the expenses that are associated with higher reliance on federal grants, like large Medicaid populations. The short version here is that Connecticut has an affluent population, high tax collections, high total revenue, and a highly progressive tax code—I’ll get to that in a minute—but it isn’t working.

Connecticut is feeling the pressure of sustained outmigration of individual and businesses alike. To those outside the state, it’s often perplexing, which is perhaps why The Atlantic asked “What on Earth is Wrong with Connecticut?” in 2017, while Slate, somewhat less inquiringly, declared “Something Has Gone Wrong with Connecticut.” Businesses are relocating. Individuals are uprooting themselves, particularly high net worth individuals whose absence on the tax rolls is felt intensely.

Too often, the response to this exodus has been to raise taxes on those remaining, which only hastens future departures. Instead, this body should look at ways to restructure the tax code to reduce impediments to growth and business retention. The tax code is by no means the only reason for departures from the state, but it is an important contributing factor, and vitally, it is one within the power of this body. Improvements to the economic efficiency of the tax code are sorely needed, and I’d like to take just a couple of minutes to walk through a few of the reforms reflected in H.B. 7410.

Connecticut’s corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. , as you know, has two components, a traditional tax on net income and an alternative minimum tax on net assets, with businesses paying the greater of 7.5 percent of net income or 3.1 mills on the value of their capital stock up to a cap of $1 million in liability. A surtax on the net income calculation, set at 10 percent last year, has sunset, but is up for reauthorization under the governor’s budget proposal, and would set a corporate income tax rate of 8.25 percent.

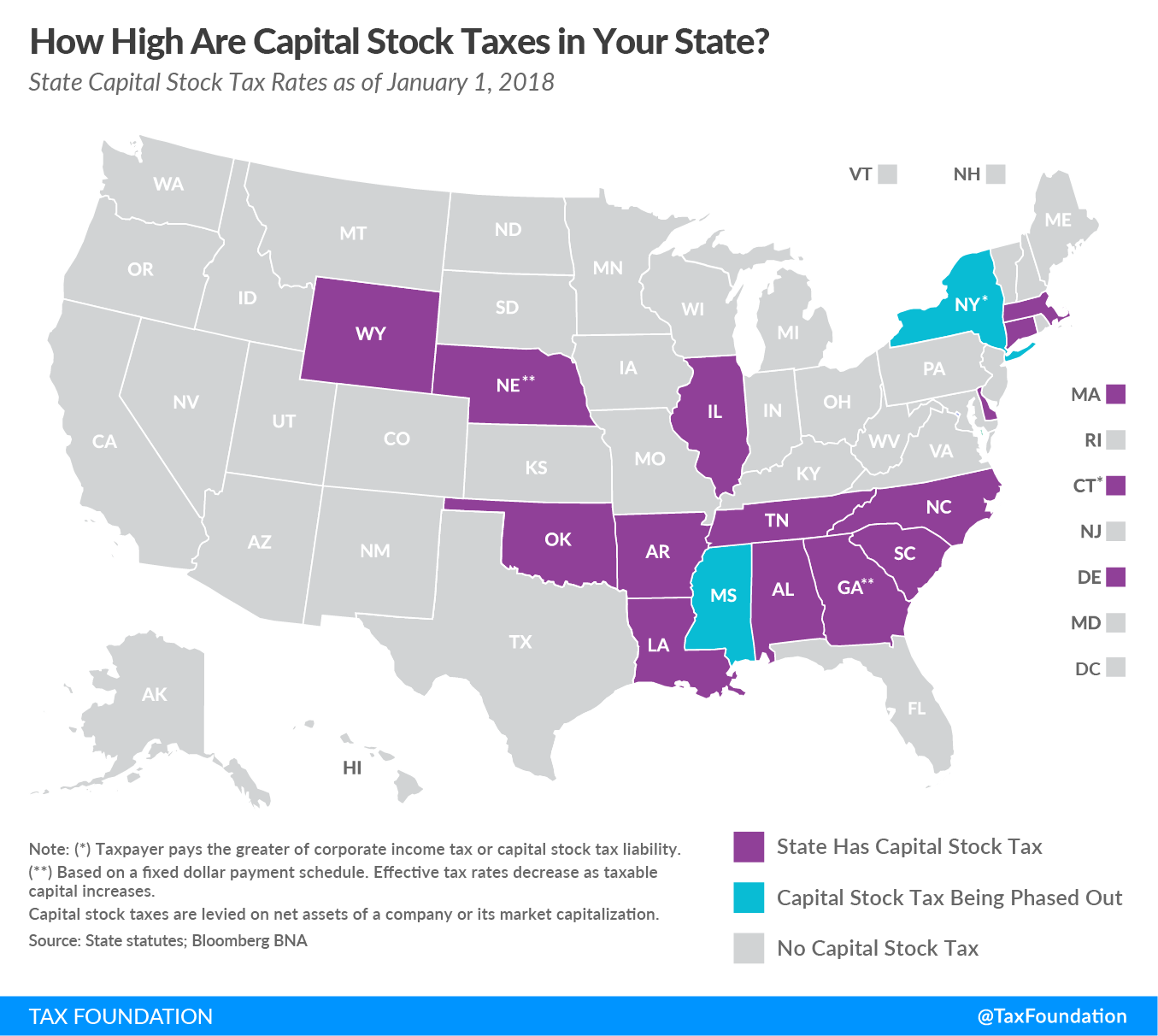

This is a capital stock tax designed as an alternative minimum tax, and its impact is heaviest on low-margin, capital intensive businesses. That can describe some businesses for long stretches, but it also describes many businesses that are just starting up or which are going through a slump—times when they can least afford an extra layer of taxation not tied to ability to pay. It’s a tax on capital accumulation, paid when the company isn’t earning returns to capital. Sixteen states still have capital stock taxes, though four are capped at $20,000 or less, and two states—New York and Mississippi—are currently phasing them out.

Even net income taxes can diverge from ability to pay, however, in part due to their one-year snapshot approach: a company which has $10 million in profit in year one and $5 million in losses in year two cannot really be said to have $10 million in overall profits, yet the corporate income tax would have been imposed on that entire amount. Net operating losses exist to help limit and smooth liability for companies over the business cycle. Connecticut, however, limits the carryforward of the net operating loss deduction to 50 percent of tax liability in any given year, keeping companies with cyclical income at a competitive disadvantage. This bill would allow these companies to come closer to paying a tax on average profitability by adopting the federal government’s new 80 percent cap in lieu of the state’s current 50 percent cap, along with an unlimited carryforward period.

The bill also creates an exemption for $25,000 in tangible personal property (TPP). The state has reduced its reliance on TPP taxes over the years, including exempting most machinery and equipment, but some tax remains. Far more than the tax, for many payers, is the compliance cost, since the levy is taxpayer active, meaning that businesses must fill out forms identifying all of their personal property subject to taxation and detailing relevant attributes including, but not limited to, a physical description, the year of purchase, the purchase price, and any identifying information, like serial numbers. The tax is to be remitted upon the depreciated value of each article of personal property. It can be a lot of work for a very small amount of liability.

An observation here: as I read the language of the introduced bill, it appears to provide an exemption for all items of tangible personal property with a value of $25,000 or less, whereas I believe the intention—certainly the intention of the Commission when it recommended a threshold—was to create an aggregate threshold of $25,000 in tangible personal property. I don’t have a Connecticut-specific estimate for the cost of exempting $25,000, but we do know that simply exempting taxpayers with $10,000 or less in taxable personal property would eliminate liability for 46 percent of current taxpayers at a cost of one-seventieth of one percent of property tax revenue. A reasonable threshold can have a significant impact on small businesses, which no longer have to deal with significant compliance burdens, and a negligible impact on any locality’s revenue collections.

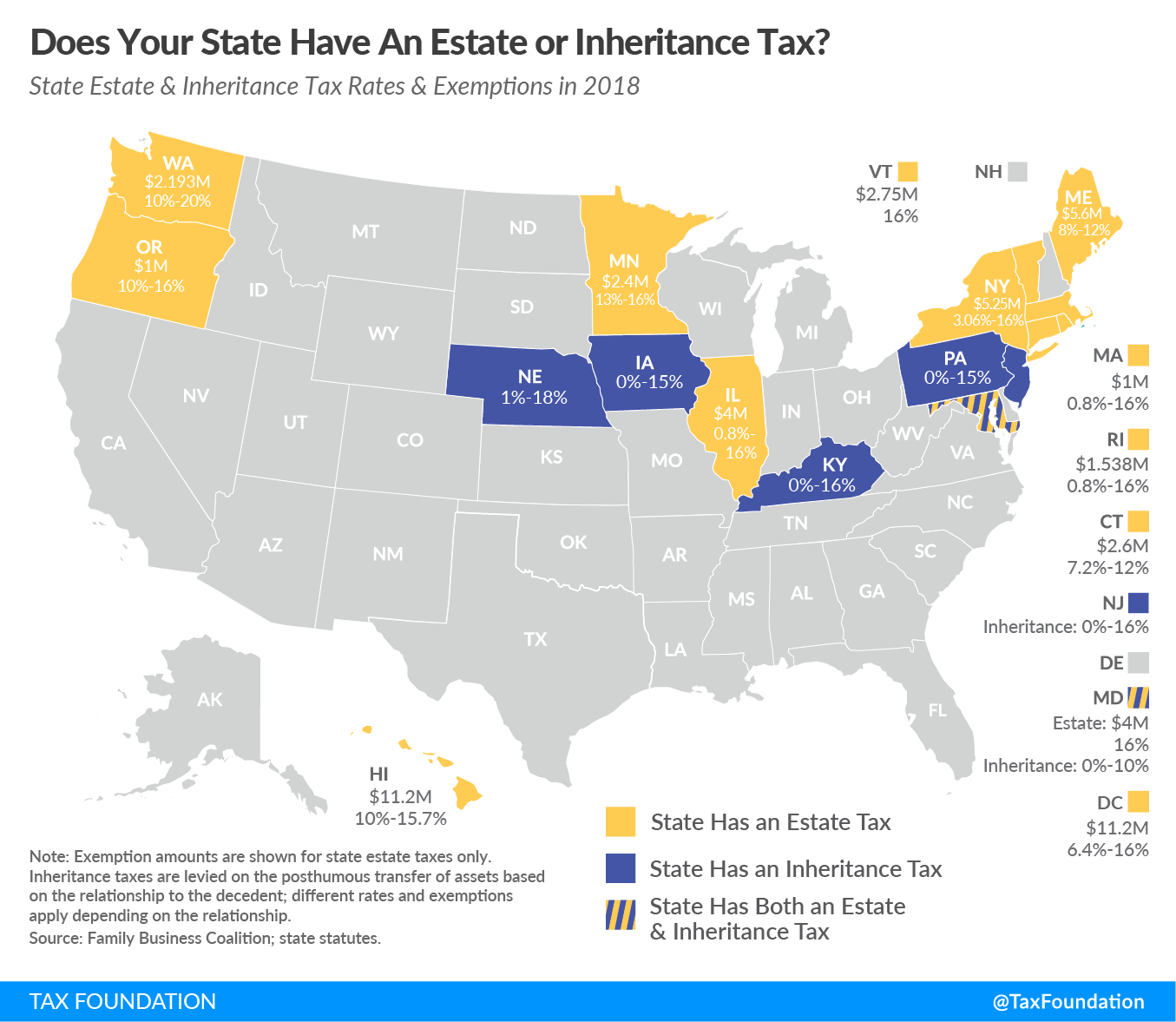

The bill also repeals the estate and gift taxA gift tax is a tax on the transfer of property by a living individual, without payment or a valuable exchange in return. The donor, not the recipient of the gift, is typically liable for the tax. , a significant step, but one that would put Connecticut in line with most other states: only 17 states still have an estate or inheritance taxAn inheritance tax is levied upon the value of inherited assets received by a beneficiary after a decedent’s death. Not to be confused with estate taxes, which are paid by the decedent’s estate based on the size of the total estate before assets are distributed, inheritance taxes are paid by the recipient or heir based on the value of the bequest received. , following repeal of Delaware’s estate tax last year. Studies show that those potentially affected by estate taxes undertake substantial economically inefficient tax avoidance activities that reduce gross state product and reduce collections from other taxes—and of course, the problem is particularly acute if the tax drives the wealthiest residents out of state several years prior to their death, depriving Connecticut of potentially years of income and other tax revenue. And we know that migration happens: a one percentage point increase in the estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. rate in a state, for instance, is associated with a nearly 4 percent decline in the number of estates worth $5 million or more.

And last but certainly not least, H.B. 7410 broadens the sales tax base, as does the governor’s budget—a modernization that is long overdue. Base erosion as the economy has become more service-oriented, and as select goods have been exempted from the base, has reduced the stability of the sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. , and the transition to a more service-oriented economy has made the sales tax more regressive, as it is least imposed on the sort of transactions that are most associated with high earners. A well-designed sales tax would fall on all final consumption—goods and services—but not on intermediate transactions, to avoid tax pyramiding. Connecticut’s system is far from this ideal, but H.B. 7410’s changes would be a significant step in the right direction.

These reforms are among those discussed in the Commission’s report, and in a separate paper produced by the Tax Foundation. We also noted the recapture provisions in the individual income tax, and the inefficiency of some corporate tax credits, as other possible avenues for reform. There are now competing proposals before this body with a different balance of tax changes and differing revenue goals. Some of that is above my pay grade. But what I do want to leave you with is this: Connecticut’s tax code is outdated and unnecessarily skewed against economic growth. Past efforts at patching up revenue deficiencies without implementing structural reform have proven just that—patches, and often not even very good ones. Going down the same path as before will yield the exact same results. Only with structural reforms is there an opportunity to reverse the state’s troubling trendlines.