While tax rates matter to businesses, so too does the measure of income to which those taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rates apply. The corporate income tax is a tax on profits, normally defined as revenue minus costs. However, under the current tax code, businesses are unable to deduct the full cost of certain expenses—their capital investments—meaning the tax code is not neutral and actually increases the cost of investment.

Under the U.S. tax code, businesses can generally deduct their ordinary business costs when figuring their income for tax purposes. However, this is not always the case for the costs of capital investments, such as when businesses purchase equipment, machinery, and buildings.

Typically, when businesses incur capital investment costs, they must deduct them over several years according to preset depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. schedules, instead of deducting them immediately in the year the investment occurs. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 alleviated the tax code’s bias against short-lived capital investments. However, the full expensing provision is temporary and doesn’t apply to capital investments with longer lives.

For investments ineligible for full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. , the delay in taking deductions means the present value of the write-offs (adjusted for inflation and the time value of money) is smaller than the original cost. How much less valuable depends on the rate of inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. and the discount rate. The delay effectively shifts the tax burden forward in time as businesses face a higher tax burden today because they cannot fully deduct their costs, and it decreases the after-tax return on the investment.

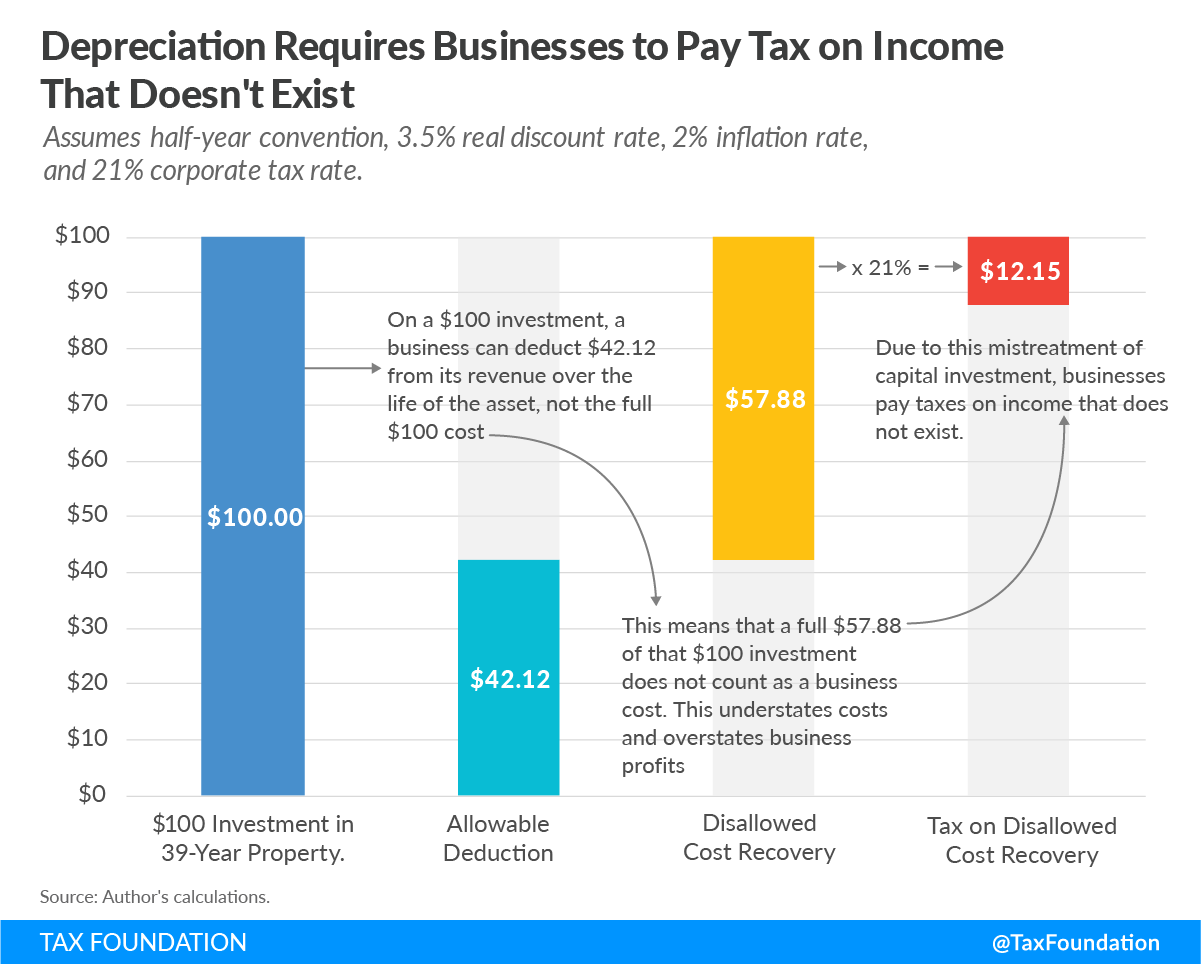

As illustrated below, this treatment understates costs and overstates profits, which in turn leads to a greater tax burden that increases the cost of the investments.

Currently, capital investments in nonresidential buildings—a type of investment that does not qualify for full expensing—must be depreciated over a 39-year period. Under current law, in present value terms, businesses would only be able to deduct $42.12 of their initial $100 investment over the 39-year recovery period, while the remaining $57.88 of costs would never be subtracted from revenue. The business would owe income tax on the overstated profit, resulting in a present value tax burden of $12.15, on income that doesn’t exist, which reduces the rate of return on the $100 investment.

When a business decides whether to make an investment, it adds up the cost of doing so, including taxes, and weighs that cost against the revenue expected over the life of the asset. Cost recovery systems that fall short of full, immediate expensing deny the investor a tax claim for part of the cost of production and increase the cost of making the investment.

Ultimately, this means that the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. is biased against investment in capital assets to the extent that it makes the investor wait years or decades to claim the cost of machines, equipment, or factories on their tax returns. Full expensing for all types of assets would bring neutrality to the corporate income tax by allowing businesses to deduct the full cost of capital investment.

Note: This is part of our “Business in America” blog series

- The Lowered Corporate Income Tax Rate Makes the U.S. More Competitive Abroad

- Corporate and Pass-through Business Income and Returns Since 1980

- Firm Variation by Employment and Taxes

- 2017 GDP and Employment by Industry

- Pass-Through Businesses Q&A

- State Corporate Income Taxes Increase Tax Burden on Corporate Profits

- Marginal Tax Rates for Pass-through Businesses Vary by State

- Taxes on Capital Income Are More Than Just the Corporate Income Tax

- Not All Tax Expenditures Are Equal