Testimony before the D.C. Council Committee on Finance and Revenue on B22-460

February 1, 2018

Chairman Evans, Members of the Committee,

My name is Scott Drenkard, and I’m an economist and director of state projects at the TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Foundation. For those unfamiliar with the Tax Foundation, we are a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that has monitored fiscal policy at all levels of government since 1937. We have produced the Facts & Figures handbook since 1941, we calculate the State Business Tax Climate Index each year, and we have a wealth of data, rankings, and other information at our website, www.TaxFoundation.org.

I am also a Ward 6 resident and care deeply about the trajectory of our District. In 2014, my colleagues and I played a citizen education role during the legislative process of D.C.’s beneficial tax reform, which broadened tax bases, lowered tax rates, and improved tax fairness in the District.

I’m pleased to have the opportunity to speak today with regard to B-22-460, a bill to increase the tax on cigarettes by $2.00 per pack, to a total excise tax rate of $4.50 for each pack sold. While the Tax Foundation takes no position on legislation, I’d like to offer some of our findings from research we have published on this issue in the last few years.

Cigarette Taxes Disproportionately Harm Low-Income Individuals

Cigarette taxes occupy a policy space at the intersection of fiscal and public health priorities. Because these targeted tax increases are so multifaceted, they must be examined based not just on their intentions, but on how they impact behavior and how they fit in with the overall tax mix of a state.

In 2014, one of the priorities of the D.C. Council in enacting comprehensive tax reform was to build a system that worked for everybody. That’s why the final package (now law) balanced base broadening, rate lowering, an expansion of the earned income tax credit, and business reforms that helped all D.C. residents—businesses, individuals, families, and those struggling to get by—to make the District a better place to live and work.

Cigarette tax increases, though aimed at improving public health, are very regressive. According to a 2009 Gallup study, 34 percent of the lowest-income individuals (individuals with annual incomes of $12,000 or less) in the U.S. use cigarettes, as opposed to 13 percent of high-income Americans (those with yearly earnings of $90,000 or more). In other words, “more than half of today’s smokers (53%) earn less than $36,000 per year—making cigarette taxes highly regressive.”[1]

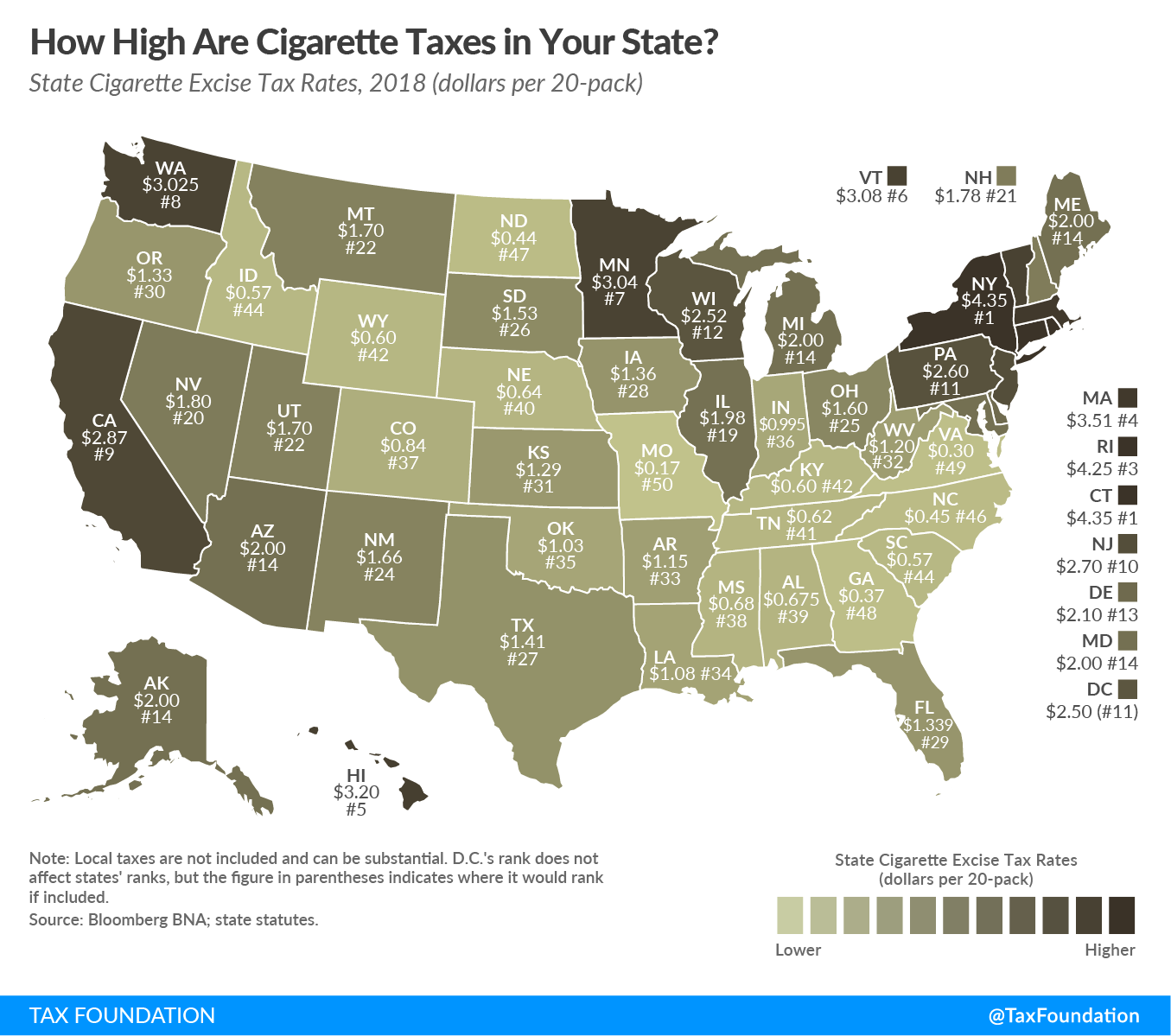

Despite this reality, the District currently levies the 11th highest cigarette tax in the country at $2.50/pack (Figure 1). If this proposal passes, the excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. on cigarettes would be $4.50 per pack, the highest state rate in the country.[2]

Figure 1.

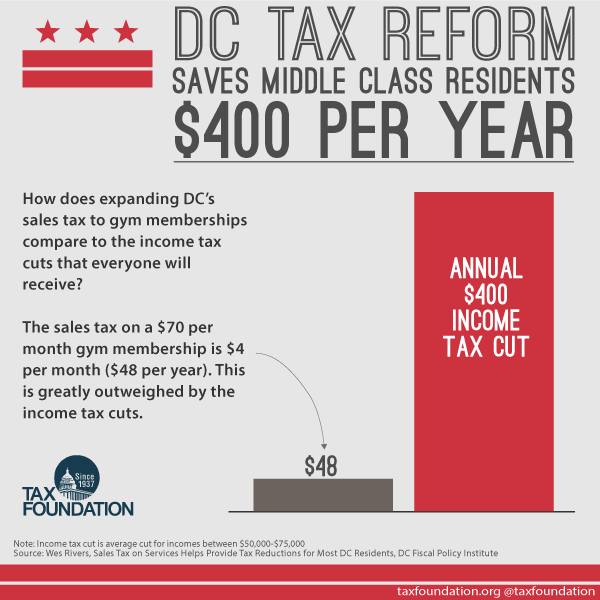

This significantly increased burden would represent a $700+ annual tax increase for a pack-per-day smoker. If this does not seem like a significant sum, recall that one of the major selling points of the District’s 2014 tax reform campaign was that it saved middle-class residents $400 per year in income tax liability. This was a fact my colleagues and I made great effort to communicate to our District friends and neighbors (Figure 2).[3]

A cigarette hike of this magnitude would claw back any benefits conferred to those middle-class residents on their District individual income taxes if they happen to smoke—plus more.

Figure 2. 2014 Tax Foundation D.C. Tax Reform Educational Materials

Increasing Cigarette Taxes Will Exacerbate Black Markets

Another unintended consequence of high taxes on cigarettes is that large disparities in taxes among states encourage illicit movement of cigarettes across state lines to evade taxes.

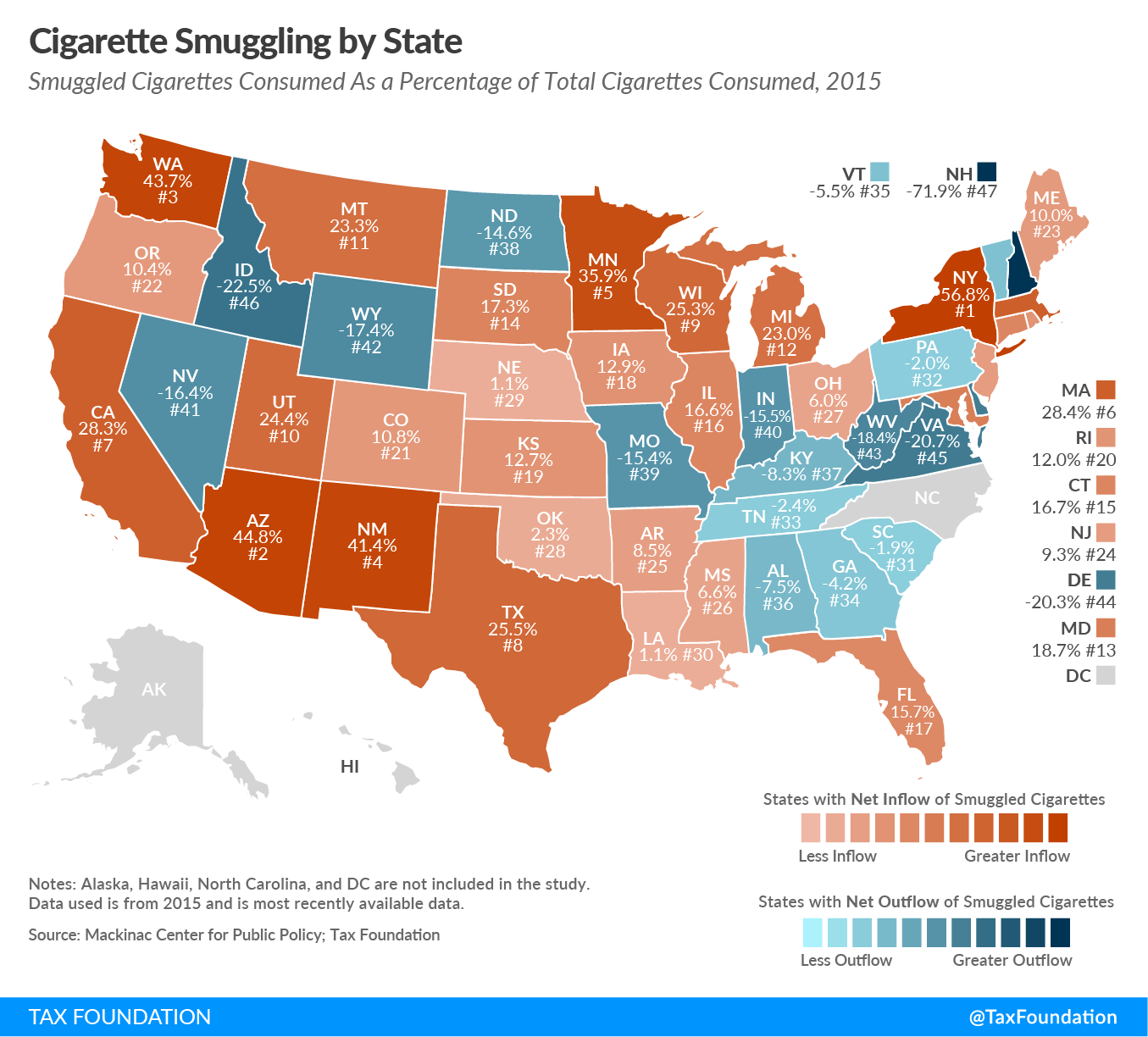

Figure 3.

This problem is larger than many Americans are aware of. Each year, Professor Todd Nesbit of Ball State University, Michael LaFaive of the Mackinac Center, and myself release updated estimates of how prevalent cross-border sales of cigarettes are. Our most recent estimates show that in New York, which has the highest state excise tax on cigarettes in the nation at $4.35, 56.8 percent of the cigarette market is smuggled in from other locales (Figure 3).[4]

This cigarette smuggling takes a variety of forms. Sometimes it is the result of sophisticated crime rings that move large quantities of tobacco from low-tax to high-tax states, while other times it is more casual, with smokers themselves just stocking up on cigarettes when they happen to be in a low cigarette-tax state and bringing those cigarettes home for personal consumption.

In D.C., we have a big problem to worry about in that Virginia is just a short Metro ride away and only taxes cigarettes at $0.30, meaning each Virginia pack would offer a $4.20 tax advantage if purchased across the river, and each carton would offer a $42 tax advantage.

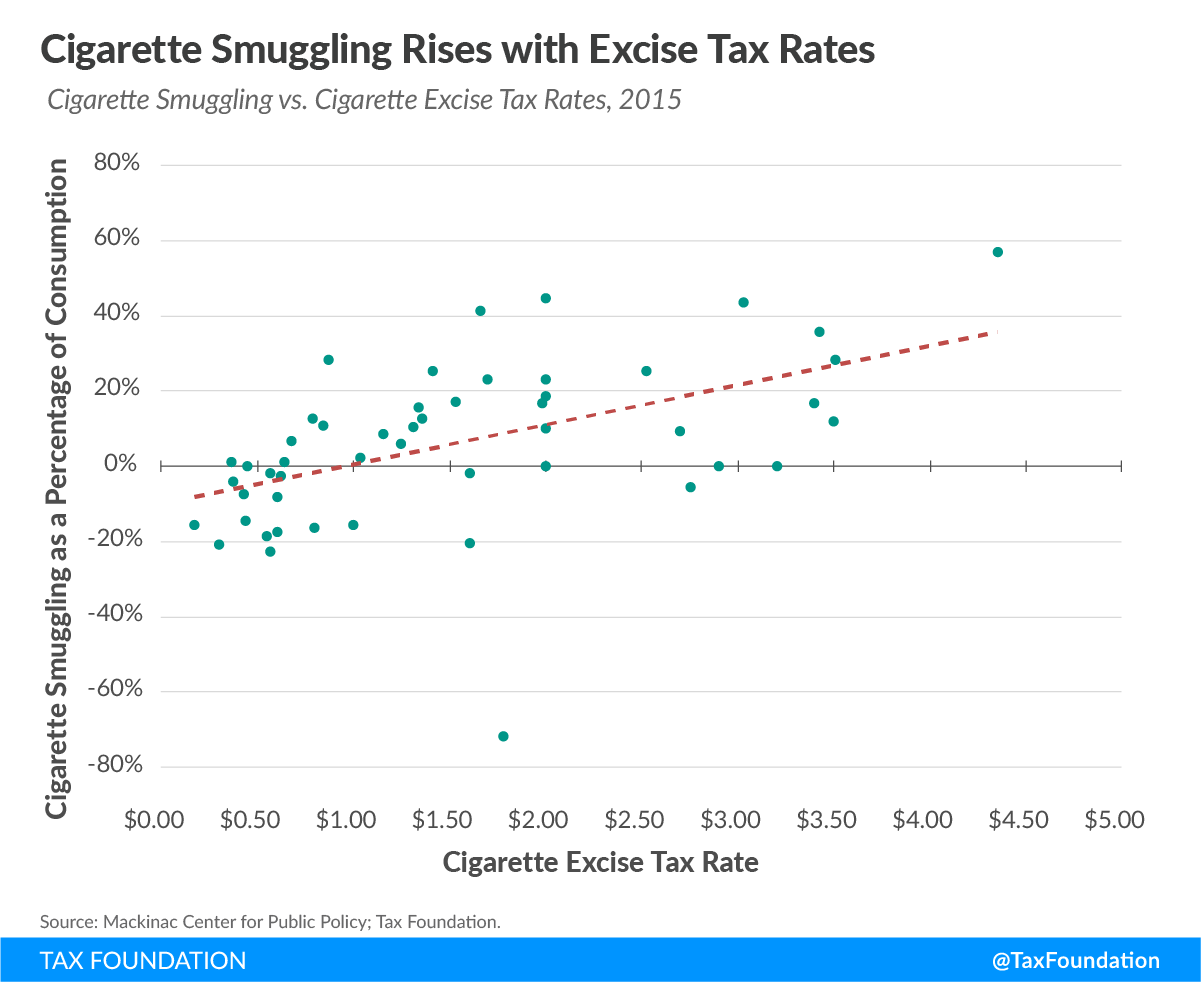

Figure 4.

One experience I had really made the magnitude of this issue sink in for me. A few years ago, I was asked to testify before the U.S. Senate Finance committee on this cross-border issue, and I wanted to see how easy it was to procure an improperly stamped pack of cigarettes. Even I was surprised that at the very first D.C. bodega I visited, the pack of cigarettes I bought had a Virginia tax stamp on it. This is illegal—but the practice will likely grow in prevalence if District cigarette tax rates increase.

As demonstrated in Figure 4, cigarette smuggling is higher in jurisdictions with higher cigarette excise taxes, and it would not be unanticipated to see smuggling rates of 40 percent—or above, given our proximity to Virginia—should a rate of $4.50 per pack be adopted here.[5]

Cigarettes coming from improper sources has troubling implications for tobacco control. One of the first glaring impacts is that as more and more cigarettes are sold outside of legal means, standard controls like age restrictions are less stringent.

Cigarette Taxes Introduce Budget Instability

One other item for this committee to be particularly aware of is the long-term budgeting impacts of leaning on cigarette taxes for revenue for general government services.

As smokers are likely to procure more cigarettes from across state lines, revenue numbers will take a hit. Additionally, since 1965, when the Surgeon General released its first report, per capita consumption of cigarettes has decreased steadily each year as more Americans make a better choice to quit for their health. This is a positive public health outcome, but it also means that cigarette tax revenues are a declining revenue stream, and are never a way to fund important recurring government programs.[6]

I’ve always found this last observation interesting, because tax hike proposals like this are counting on consumers to continue smoking, so the state can continue to fund public education, transportation, and public services on top of their behavior.

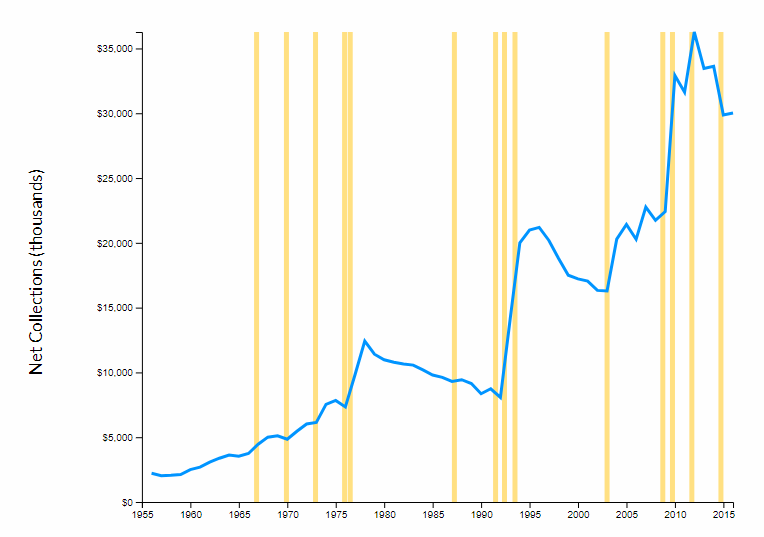

As Figure 5 demonstrates, the District’s cigarette tax revenues enjoy momentary bumps in revenue after rate hikes (shown in the figure with vertical yellow bars), but then fall off as consumers quit or procure cigarettes in other states with lower taxes.

These continual and frequent rate hikes are unsustainable, and if our tax were $4.50 per pack, we would likely collect less still in revenue than we do today.

Figure 5. Cigarette Taxes Do Not Provide Stable Revenue

D.C. Cigarette Tax Collections and Rate Increases, 1955-2015

Taxing Electronic Cigarettes Harms Public Health

Finally, the proposed bill would institute higher taxes on electronic cigarettes at a rate equivalent to traditional incinerated cigarettes. The public health literature, however, does not support this approach, as electronic cigarettes are categorically less risky than traditional cigarettes.

For example, a recent study in the Journal of Public Health Policy finds that traditional cigarettes contain as much as 5,300 chemicals, while e-cigarettes contain primarily three: nicotine, glycerin, and propylene glycol. That study concluded, “Other than TSNAs and DEG, few, if any, chemicals at levels detected in electronic cigarettes raise serious health concerns.”[7]

Public Health England, the health research arm of the UK government, finds that vapor products carry 90 to 95 percent less risk than traditional cigarettes.[8] Another recent study in Tobacco Control finds that e-cigarettes have potential as a tobacco-cessation method, because they curb nicotine cravings.[9] My brother used electronic cigarettes to help quit cigarettes, and I’m glad the option was available to him.

In my view, these products should not face the same tax rates as combustible tobacco, and so a renewed look D.C.’s practice of tying the tax rate on electronic cigarettes to the tax rate on traditional cigarettes is likely warranted.

Conclusion

While a cigarette tax increase can seem like a productive step for public health, the decision carries with it some undesirable obstacles. I hope these suggestions are useful, and I look forward to your questions. Thank you.

[1] Lydia Saad, “Cigarette Tax Will Affect Low-Income Americans Most,” Gallup News, April 1, 2009, http://news.gallup.com/poll/117214/cigarette-tax-affect-low-income-americans.aspx.

[2] Colin Cook, “How High Are Cigarette Taxes in Your State?” Tax Foundation, Jan. 25, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-cigarette-tax-rates-2018/.

[3] Tax Foundation, “Here’s What the Experts are Saying about D.C.’s Tax Reform Proposal,” June 19, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/here-s-what-experts-are-saying-about-dc-s-tax-reform-proposal/.

[4] Scott Drenkard, “Cigarette Taxes and Cigarette Smuggling by State, 2015,” Tax Foundation, November 6, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/cigarette-tax-cigarette-smuggling-2015/.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Scott Drenkard and Tom VanAntwerp, “How Stable is Cigarette Tax Revenue?” Tax Foundation, May 10, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/cigarette-tax-revenue-tool/.

[7] Zachary Cahn and Michael Siegel. “Electronic cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy for tobacco control: A step forward or a repeat of past mistakes?” Journal of Public Health Policy 32 (February 2011), http://www.palgrave-journals.com/jphp/journal/v32/n1/full/jphp201041a.html.

[8] A. McNeill et al., “E-Cigarettes: An Evidence Update.” Public Health England, August 19, 2015, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/457102/Ecigarettes_an_evidence_update_A_report_commissioned_by_Public_Health_England_FINAL.pdf.

[9] Christopher Bullen, et. al., “Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e Cigarette) on desire to smoke and withdrawal, user preferences and nicotine delivery: randomized cross-over trial,” Tobacco Control 19, no. 2 (2010), 98-103.