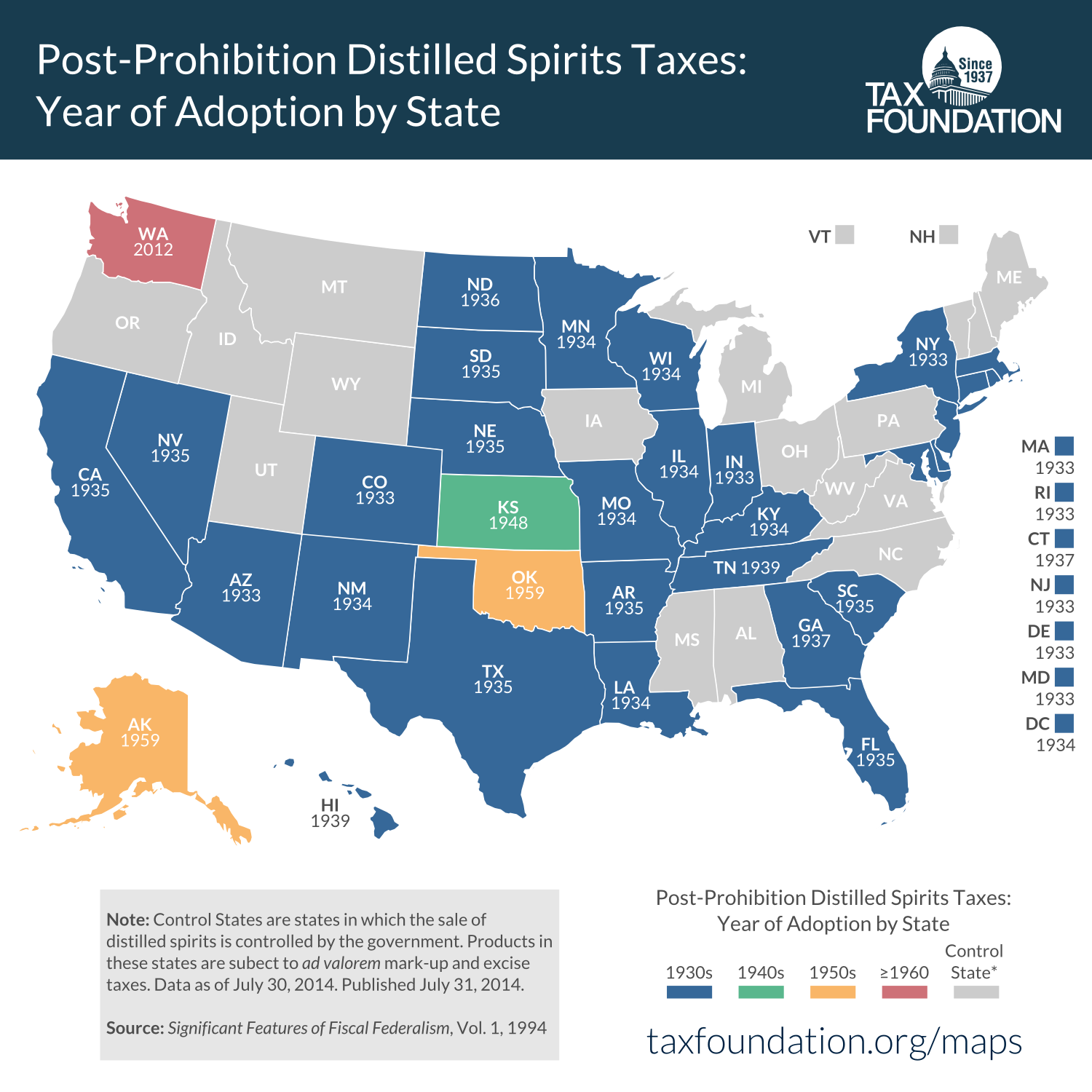

This week’s taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. map takes a look at when each state first adopted its distilled spirits excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. , if it has one. Federal taxation of alcohol dates back to the earliest years of the republic but state excise taxes all followed swiftly on the heels of the Twenty-first Amendment. With the end of federal alcohol prohibition in 1933, states retained the authority to permit or prohibit alcohol sales. Most states quickly legalized, either as “liquor control states” shown in gray, or with private liquor sales, like the color-coded states. No state legalized prohibition without swiftly applying high taxes to liquor, though states varied in when they ended prohibition, with Oklahoma remaining a constitutionally “dry” state until 1959. Among states that adopted government liquor sales monopolies after ending prohibition, only Washington State has since privatized liquor sales.

(Click on the map to enlarge it. Reposting policy)

In 1791, almost immediately after the Constitution was ratified, Alexander Hamilton pushed for a national excise tax on liquor as a means of raising revenue to pay down the national debt. Hamilton believed a tax on distilled spirits would be useful both because they were widely consumed, and thus represented a fairly large tax base, but also because he perceived distilled spirits to be a luxury good, and thus a tax might be fairly progressive. Many social reformers also believed distilled spirits were damaging to society, and so looked favorably on higher taxes. These arguments for excise taxes, that they tax socially damaging goods, or luxury goods, or serve as advantageous and politically popular revenue sources, continue today in various forms.

In reality, the tax turned out to be disproportionately burdensome on poor- and middle-income farmers living in the territories and new states beyond the Appalachian mountains. The traditional distilled drinks of “Western states” (such as Bourbon from my home state of Kentucky, or Tennessee Whiskey) arose as ways of turning grain into a product that could be easily and profitably sold in the urban centers of the east. The new tax, then, injured these grain farmers and western pioneers. This led to the so-called Whiskey Rebellion, wherein disgruntled westerners rose up against the government, only to be swiftly crushed by George Washington and almost 13,000 militia. Throughout the 19th century, federal excise taxes on distilled spirits remained a major revenue item, so large that prohibition of alcohol, while politically popular, was considered impossible until after the Sixteenth Amendment permitted an income tax in 1913.

States also taxed alcohol, and especially distilled spirits. However, prior to prohibition, state alcohol taxation tended to be occupationally-focused, requiring licensing by producers and sellers of alcohol at an approximately fixed rate, rather than a strict excise tax. Even so, these taxes were a large component of many states’ tax collections.

There were also some states that, far from taxing alcohol, enacted state-level prohibition far earlier than the nation on the whole. The first state to enact prohibition lasting until national prohibition began was Kansas, in 1880, and the state did not repeal until 1948, giving it the longest time under prohibition of any state in the union. Other states with early prohibition regimes include Maine, Vermont, Iowa, North Dakota, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Oklahoma, North Carolina, Tennessee, Oregon, West Virginia, Washington, Montana, and others. Many of these early-prohibition states became liquor control states after the end of national prohibition. Liquor control states also tend to have higher effective taxes on distilled spirits.

Oklahoma’s last-in-the-nation end of prohibition came after decades of referendums as urban voters in favor of legalization repeatedly failed to defeat rural voters opposed to it. Finally, however, legalization won out as Oklahoma’s revenue needs increased, and legalization was seen as an alternative to other taxes. Perhaps more interestingly, the pro-legalization Governor Howard Edmondson (D) launched an aggressive enforcement campaign, raiding establishments illicitly serving alcohol and enforcing Oklahoma’s laws with unprecedented consistency. Even advocates of prohibition were taken aback by the drastic consequences of full enforcement of the laws they claimed to support, and so the “dry” coalition collapsed.

Since the end of prohibition, state liquor policies have been remarkably stable. While rates and markups in privatized and control states have varied, only Washington State has made the switch from liquor control to privatization. As part of that change, the state levied new taxes and fees on distilled spirits, leading to even higher liquor prices. Indeed, throughout the history of liquor taxation in the United States, decreasing control or regulation has in almost all cases been paired with (and often motivated by) increased excise taxes.

Read more on alcohol excise taxes here.

Follow Lyman and Richard on Twitter.

Share this article