Testimony Before the United States Joint Economic Committee

In December, Congress passed a historic taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reform package, which made the U.S. tax code more competitive. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is not perfect, but as passed, it is expected to grow the U.S. economy, resulting in a higher level of GDP, higher wages for workers, and more full-time equivalent jobs.

However, economic growth, spurred by tax reform, takes years to occur. In this testimony, I discuss the relationship between taxes and economic growth, the pro-growth impacts of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and its distributional impact. Additionally, I investigate the timing of these changes and whether there is economic evidence of changes thus far.

Why Taxes Affect Economic Growth

To understand how tax policy affects economic growth, we should begin with an understanding of what drives economic growth. Under a neoclassical economic view, the main drivers of economic output are the willingness of people both to work and to deploy capital, such as machines, equipment, factories, etc.[1] The supply of labor and capital is determined by their respective prices.

Taxes play a role in decisions to work and to deploy capital, because taxes affect the return to labor and capital. For example, the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate and cost recoveryCost recovery is the ability of businesses to recover (deduct) the costs of their investments. It plays an important role in defining a business’ tax base and can impact investment decisions. When businesses cannot fully deduct capital expenditures, they spend less on capital, which reduces worker’s productivity and wages. provisions are important determinants of the cost of capital, which affects how much people are willing to invest in new capital, and in where they will place that new capital. The individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. likewise affects how much people are willing to work by creating a wedge between what an individual is paid and what they receive after taxes.

If individuals supply more work, or if businesses supply investments in new equipment or factories, this creates more economic output. Neoclassical economics helps explains this process.

Evidence shows that of the different types of taxes, the corporate income tax is the most harmful for economic growth.[2] One key reason that capital is so sensitive to taxation is because capital is highly mobile. For example, it is relatively easy for a company to move its operations or choose to locate its next investment in a lower-tax jurisdiction, but it is more difficult for a worker to move his or her family to get a lower tax bill. Capital is, therefore, more responsive to tax changes; lowering the corporate income tax rate reduces the amount of economic harm it causes.

A common misunderstanding is that corporations bear the cost of the corporate income tax. However, a growing body of economic literature indicates that the true burden of the corporate income is split between workers through lower wages and owners of the corporation.[3] As capital moves away in response to high statutory corporate income tax rates, productivity and wages for the relatively immobile workers fall. Empirical studies show that labor bears about half of the burden of the corporate income tax.[4]

To understand why the lower corporate tax rate drives growth in capital stock, wages, jobs, and the overall size of the economy, it is important to understand how the corporate income tax rate affects economic decisions. When firms think about making an investment in a new capital good, like a piece of equipment, they add up all the costs of doing so, including taxes, and weigh those costs against the expected revenue the capital will generate. Projects where the costs exceed the benefits are not undertaken. All else constant, a higher corporate income tax could prevent a project from being undertaken.

Therefore, the higher the tax, the higher the cost of capital, the less capital that can be created and employed.[5] So, a higher corporate income tax rate reduces the long-run capital stock and reduces the long-run size of the economy.[6] Conversely, lowering the corporate income tax incentivizes new investment as previously unprofitable projects are now worthwhile, leading to an increase of the capital stock.

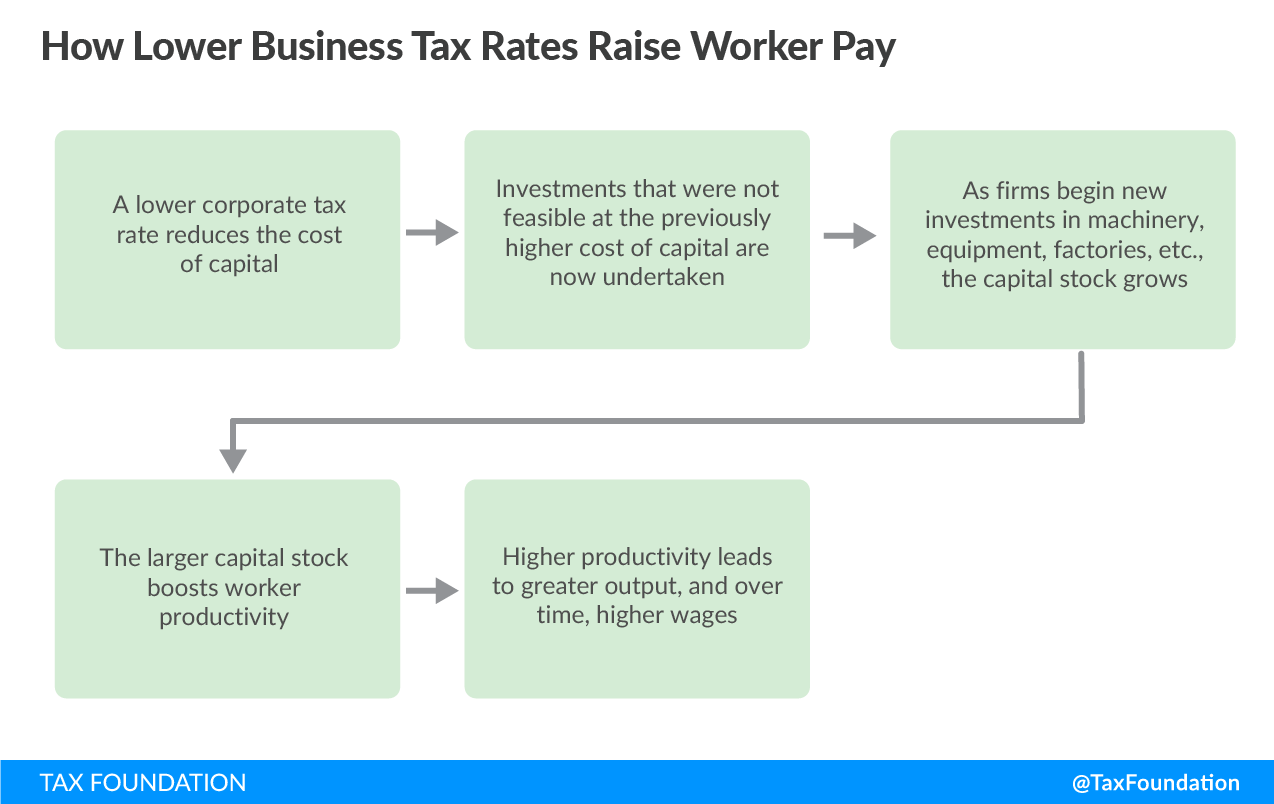

This long-run increase in the capital stock is not just beneficial for businesses. Workers benefit from this effect as well. Capital formation, which results from investment, is the major force for raising incomes across the board.[7] More capital for workers boosts productivity, and productivity is a large determinant of wages and other forms of compensation. This happens because, as businesses invest in additional capital, the demand for labor to work with the capital rises, and wages rise too.[8] Figure 1 below describes this process.

Figure 1.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeEconomic Impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act represents a dramatic overhaul of the U.S. tax code, and the results of our Taxes and Growth (TAG) Macroeconomic Tax Model indicate that the new law is pro-growth.

Just nine short months ago, the major provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act took effect. The law reduced tax rates for both businesses and individuals, limited major deductions, and created a new set of rules for companies that earn income overseas.

In the short run, the tax changes will result in a small, demand-side response as individuals’ after-tax incomeAfter-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. increases. Individuals will have lower tax burdens, which results in an increase in spending power, but these results are not the real drivers of long-run economic growth.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was designed to do more; to improve incentives in the economy, encouraging taxpayers to work more, save more, and invest more over the long term. Lowering taxes on capital and labor is expected to boost productivity, wages, and the size of the economy.

It is unrealistic to expect fiscal policy changes, like the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, to produce immediate results. Politics demand results now and spectators are eager to pass an early judgment of the new law, but unfortunately, tax reform and economic growth do not do their work within a news cycle. In fact, the current debate resembles a long car ride with your kids. An hour into the ride they kick the back of your seat and demand to know, “Are we there yet?” But these things take time and patience.

Since the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, economists across the spectrum have looked through the data and anecdotes to identify whether the anticipated economic gains are coming to fruition and how the benefits could flow through to workers and shareholders. But looking at snapshots of data is not a useful exercise; there are many conflating factors to contend with, and nine months is simply not enough time to detect long-run economic changes.

Permanent Provisions

Using a neoclassical framework, as described above, the Tax Foundation has developed a General Equilibrium Model, called the Taxes and Growth model, to simulate the effects of tax policies on the economy and on government revenues and budgets.[9] The model can produce both conventional and dynamic revenue estimates of tax policy. The model can also produce estimates of how policies impact measures of economic performance such as GDP, wages, and employment. The Taxes and Growth model can also produce estimates of how different tax policies impact the distribution of the federal tax burden on both a conventional and dynamic basis.

The Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth model estimates that the total effect of the new tax law will be a 1.7 percent larger economy, leading to 1.5 percent higher wages, a 4.8 percent larger capital stock, and 339,000 additional full-time equivalent jobs in the long run.[10] We anticipate these benefits will occur because the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act improved major incentives in the economy, but it will take time for taxpayers to respond to those improved incentives, and for those responses to boost wages and economic growth.

|

Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, November 2017. |

|

| Change in long-run GDP | 1.7% |

| Change in long-run capital stock | 4.8% |

| Change in long-run wage rate | 1.5% |

| Change in long-run full-time equivalent jobs | 339,000 |

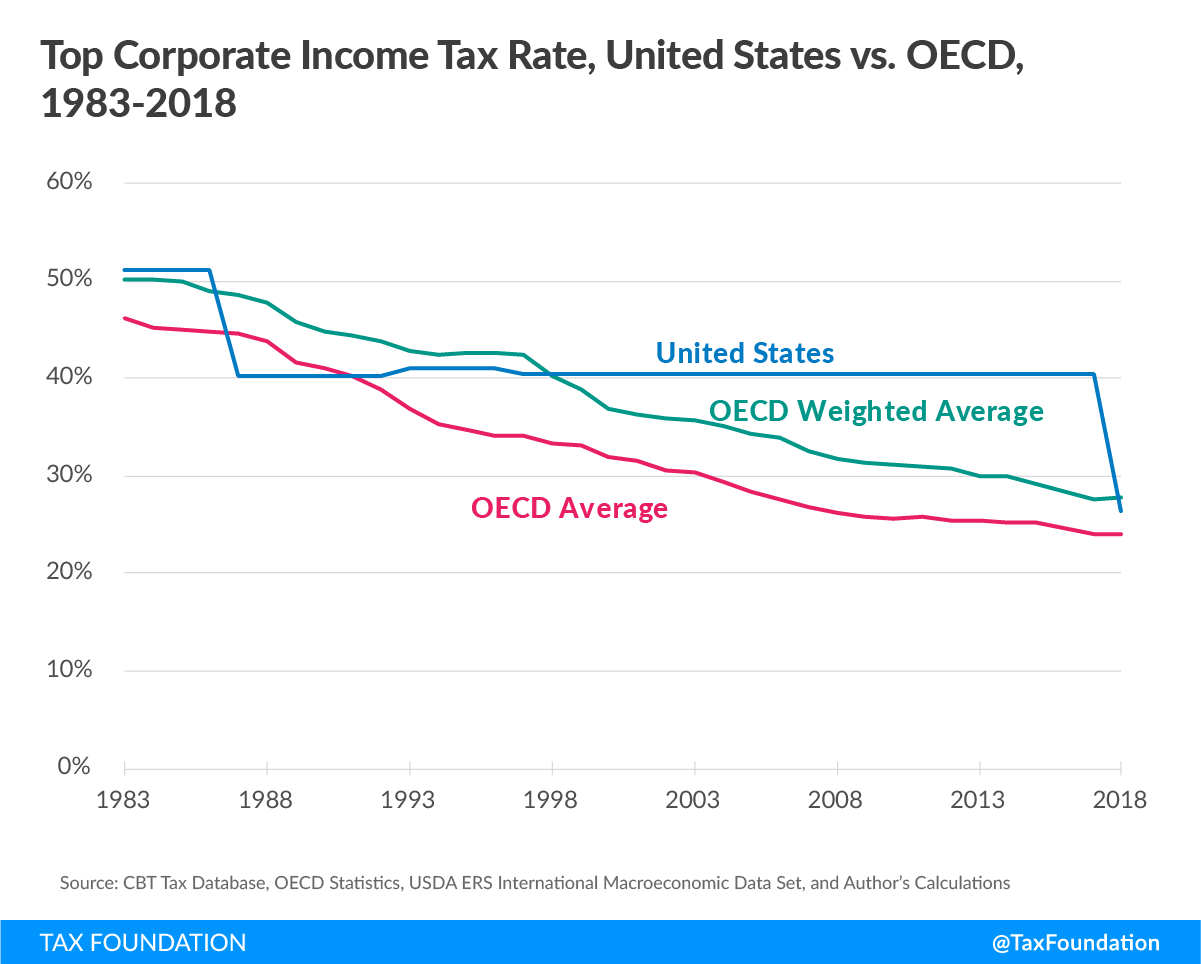

This increase in long-run economic growth is driven by the now lower corporate income tax rate, which decreased from 35 percent to 21 percent.[11] Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the United States’ high statutory corporate tax rate stood out among rates worldwide. Among countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the U.S. combined corporate income tax rate was the highest.[12] Now, post-tax reform, the rate is close to average.

Figure 2.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeAs discussed previously, the lower corporate income tax rate lowers the cost of capital, which encourages new investments in the United States. As additional investment grows the capital stock, the demand for more workers to work with the new capital will increase, leading to higher productivity, output, employment, and wages over time. This is not a process that happens overnight; companies will need to plan and then build new investments, workers will then use those new investments and become more productive, and over time this will bid up wages and increase output. Realistically, it will take years to fully assess the economic impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. And the changes won’t be as obvious as bonus checks or new projects with “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” on the memo line. It is likely that workers will see slightly higher pay increases than they otherwise would have as productivity and the economy grow faster.

Temporary Provisions

However, the long-run impacts of the law are muted. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act used a Senate budget process known as reconciliation, which required that the law may not impact the deficit after the first ten years. As such, major portions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act are set to phase out or expire. These temporary provisions frontload some of the anticipated economic growth, but because they expire, they do not contribute to the long-run impact of the new tax law. Ideally, Congress would work to make several of these provisions permanent to maximize economic growth.

100 Percent Bonus DepreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act made significant progress in improving the cost recovery treatment of business investment by enacting 100 percent bonus depreciationBonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. . Under the U.S. tax code, businesses can generally deduct their ordinary business costs when figuring their income for tax purposes. However, this is not always the case for the costs of capital investments, such as when businesses purchase equipment, machinery, and buildings. Typically, when businesses incur these sorts of costs, they must deduct them over several years according to preset depreciation schedules instead of deducting them immediately in the year the investment occurs.[13]

Delaying deductions means the present value of the write-offs (adjusted for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. and the time value of money) is worth less than the original cost, sometimes worth much less. Delayed deductions increase the cost of making an investment, which results in less capital formation, lower productivity and wages, and less output.[14]

The new 100 percent bonus depreciation provision allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of short-lived assets such as machinery and equipment, removing the tax code’s bias against these specific capital investments.

The provision is scheduled to be in effect for five years before it begins gradually phasing out at the end of 2022. Beginning in 2023, the provision would be reduced by 20 percentage points each year, for example, dropping to 80 percent in 2023, 60 percent in 2024, and so on until it expires entirely at the end of 2026.[15]

The temporary nature of the provision will incentivize businesses to make their investments sooner, while they can deduct the full cost, rather than later, when they must take depreciation deductions over longer periods. Thus, the provision will pull some investments forward, leading to faster growth in earlier years that slows back down as the provision expires in later years.[16]

On a permanent basis, 100 percent bonus depreciation would generate long-run economic growth.

|

Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, April 2018 |

|

| GDP | +0.9% |

| Wage Rate | +0.8% |

| Private Business Capital Stock | +2.2% |

| FTE Jobs | 172,300 |

The Taxes and Growth model estimates that making the 100 percent bonus depreciation provision in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act permanent would increase the size of the capital stock by 2.2 percent and long-run GDP by 0.9 percent; the larger economy would result in a 0.8 percent increase in wages and 172,300 full-time equivalent jobs.

Individual Income Tax Provisions

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act significantly lowered individual income tax rates and made aspects of the individual income tax code simpler primarily by reducing the attractiveness of itemizing deductions. However, these individual tax code provisions are all scheduled to expire at the end of 2025.

Some of the most prominent changes in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act are: the top income tax bracketA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. rate went from 39.6 percent to 37 percent and the rates for other brackets were lowered too; the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. was doubled; both the state and local tax deductionA tax deduction is a provision that reduces taxable income. A standard deduction is a single deduction at a fixed amount. Itemized deductions are popular among higher-income taxpayers who often have significant deductible expenses, such as state and local taxes paid, mortgage interest, and charitable contributions. and the mortgage interest deductionThe mortgage interest deduction is an itemized deduction for interest paid on home mortgages. It reduces households’ taxable incomes and, consequently, their total taxes paid. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced the amount of principal and limited the types of loans that qualify for the deduction. were capped; the personal exemption was eliminated; and the child tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. was doubled. The outcome of these changes has been to lower the tax rate on labor and to push filers towards choosing the standard deduction instead of itemizing, which means the process of tax filing will be much simpler.

For example, the Internal Revenue Service estimates the average time to complete an individual tax return will drop by 4 to 7 percent. Converting this to dollar terms, we estimate compliance savings could range from $3.1 billion to $5.4 billion annually.[17]

Though these tax cuts do not result in long-term economic growth because they expire, they do result in some short-term dynamic growth and revenue by increasing the incentives to work.

If the current iteration of Tax Cuts and Jobs Act goes unchanged and these parts of the bill are allowed to expire, then households will see higher tax rates and a more complicated filing system when they file their taxes in 2026. In response, individuals would reduce their labor force participation and hours worked; the temporary lowering in individual income taxes does not change long-run incentives, explaining why these temporary individual rate cuts do not add to the long-run size of the economy.

Making the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s expiring individual tax code changes permanent would result in a larger economy in the long run by permanently increasing these incentives to work and invest.[18]

According to the Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth model, making these provisions permanent would have a small, positive impact on the economy during the 2019 to 2028 budget window. The growth impact of expansion is limited, due to the extension’s timing. The provisions are currently in effect through 2025, meaning that only three years of extension are being captured in the budget window.

The economic benefits from making these provisions permanent are found in the long run, as the impacts of tax reform take several years to be fully realized. In the long run, making all individual tax provisions permanent will lead to 2.2 percent higher long-run GDP, 0.9 percent higher wages, and 1.5 million more full-time equivalent jobs. However, it would reduce federal revenues by $166 billion annually.

|

Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, April 2018 |

|

| Long-Run GDP | +2.2% |

| Wages | +0.9% |

| Jobs | +1.5 million |

Section 199A Pass-Through Deduction

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act created a deduction for households with income from pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. es—companies such as partnerships, S corporationAn S corporation is a business entity which elects to pass business income and losses through to its shareholders. The shareholders are then responsible for paying individual income taxes on this income. Unlike subchapter C corporations, an S corporation (S corp) is not subject to the corporate income tax (CIT). s, and sole proprietorships, which are not subject to the corporate income tax.

The pass-through deduction allows taxpayers to exclude up to 20 percent of their pass-through business income from federal income tax. The deduction is subject to several limits, which are intended to prevent abuse. These limits are based on the economic sector of each business, the amount of business wages paid, and the original cost of business property. These limits only apply to upper-income taxpayers.

The design of the pass-through deduction leaves room for improvement. The rules for claiming the deduction are relatively complex and will arbitrarily favor certain economic activities over others. Meanwhile, it is unlikely that the current limits on the deduction will be sufficient to prevent abuse. Finally, several features of the provision’s design will diminish its economic effect. The pass-through deduction, as currently written, will no longer be available to households beginning in 2026. The extension of the Section 199A pass-through deduction would be pro-growth, but arguably, reforms to the deduction’s structure would be more beneficial.

Growth Impacts during the Next Decade

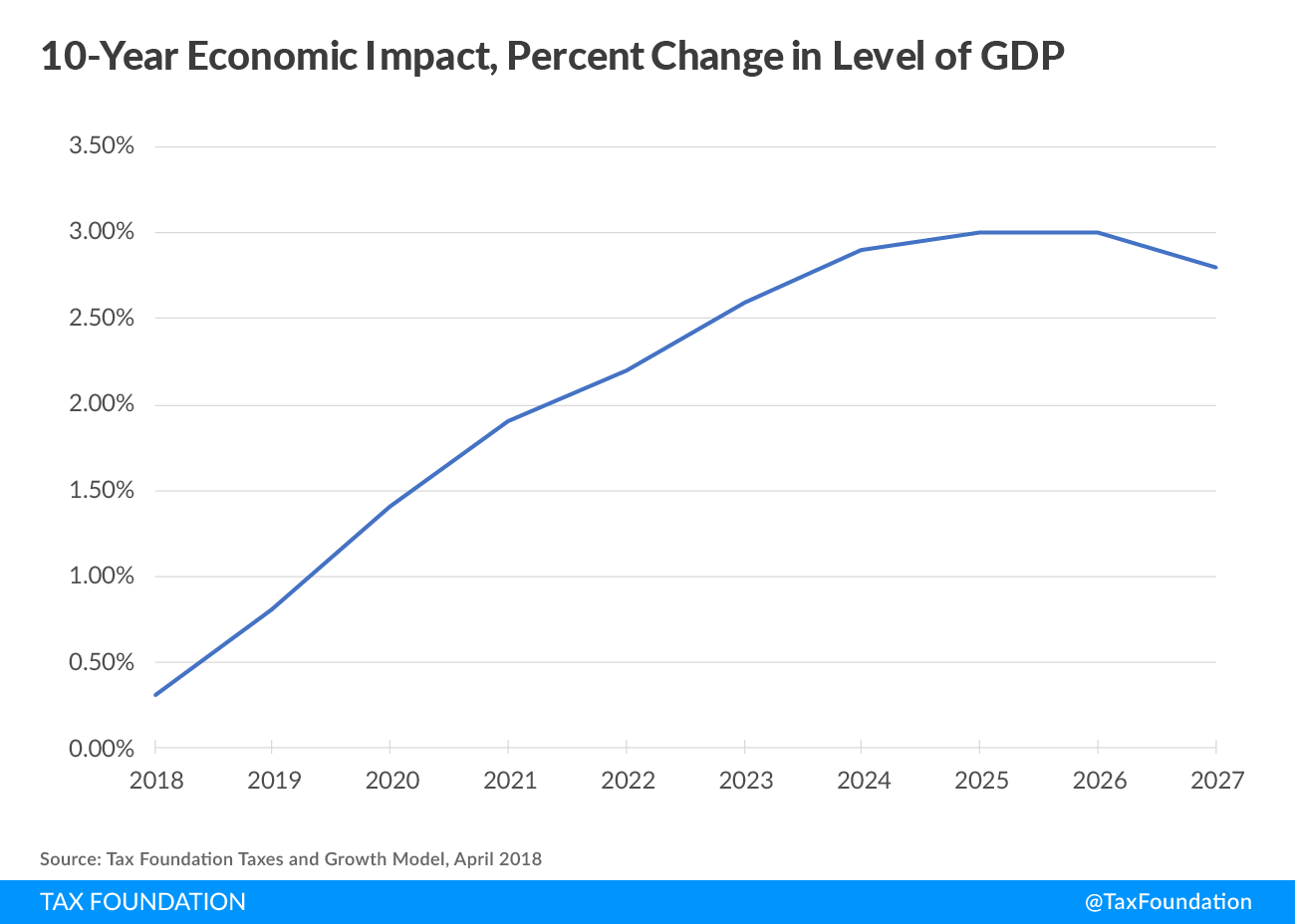

The Taxes and Growth Model is also able to model the combined impacts of these temporary and permanent provisions over the next decade. The Tax Foundation model projects that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would boost the size of the economy over the next decade. In the first few years, the economic impact will be modest as companies begin to invest more, building the capital stock. In 2018, we project the economy to be 0.3 percent over baseline and by 2020, it will be 1.4 percent over baseline. By 2025, the economy will be 3 percent over baseline—its highest point over the next decade. In 2026, when the individual provisions expire, and 100 percent bonus depreciation has fully phased out, the size of the economy will stop growing in excess of baseline and begin to shrink. By 2027, the size of the economy will be 2.8 percent larger than it otherwise would have been. On average, GDP will be about 2 percent above baseline between 2018 and 2027. By 2027, GDP will be $560 billion[19] higher than it otherwise would have been. Additionally, by 2027, GDP will have increased by a cumulative $5.3 trillion over the budget window.

Figure 3.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeThe Distributional Impact

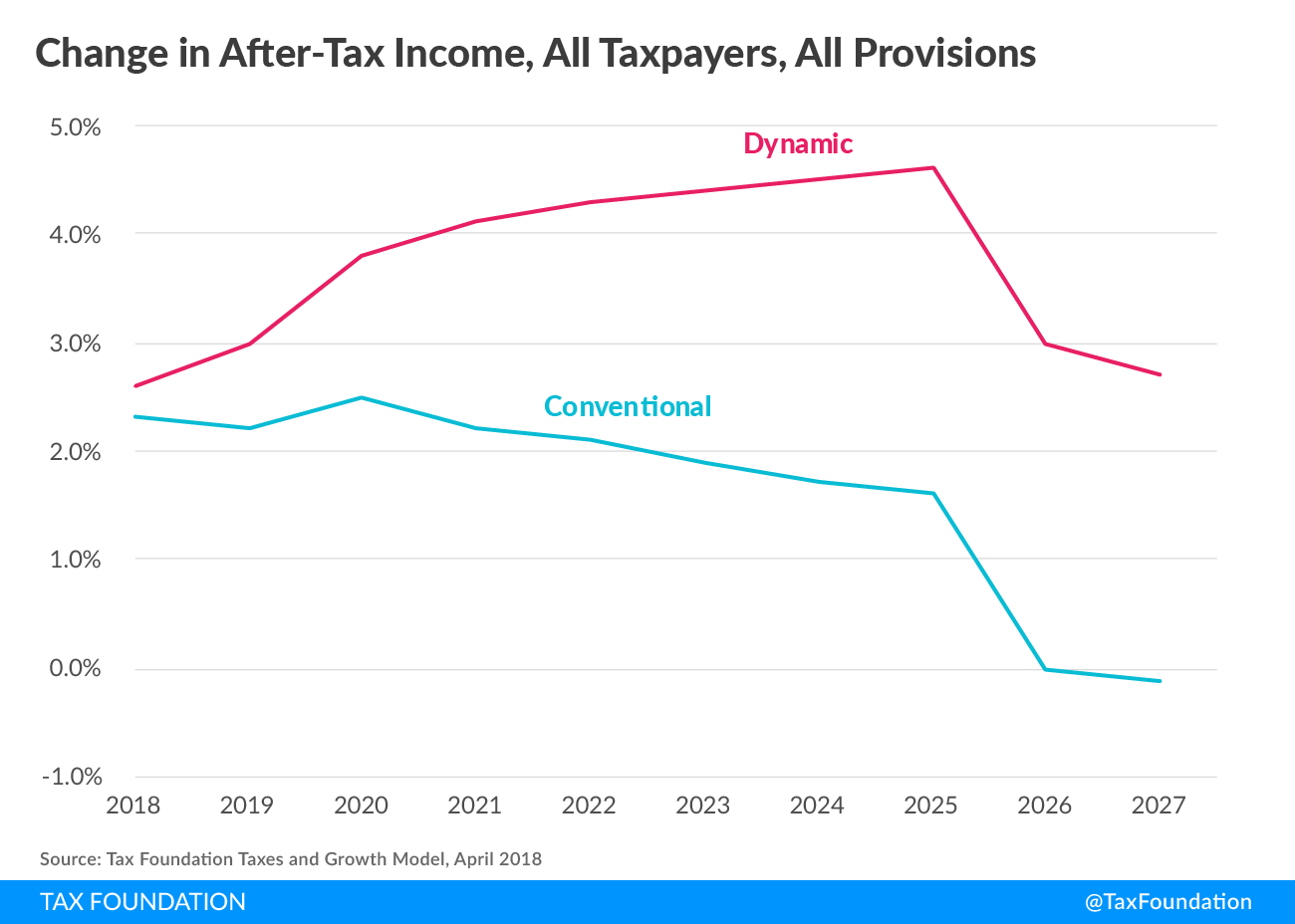

The impact of the new law on after-tax incomes of families is just as important as the broader macroeconomic benefits, and in fact, they go hand in hand. Improved incentives to work and to invest are beneficial policies in terms of the size of the economy as well as the size of after-tax incomes. Analyzing the distributional impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on both a conventional basis and a dynamic basis to account for the growing economy helps provide a clearer picture of how the provisions affect household incomes over the next decade.

The effect of lower tax liabilities from the individual income tax cuts is immediate. On a conventional basis, for example, after-tax income of taxpayers in the middle-income quintile will be 1.6 percent higher in 2018.[20] This is due to the immediate lowering of individual income tax liabilities. On the other hand, the increase in pretax income, due to the projected larger economy, takes time to materialize. For this reason, in the first few years of the tax cuts, we project that dynamic increases in after-tax incomes are only modestly higher than on a conventional basis.

But by 2022, for example, more of the economic effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act will have phased in. As a result, we project that dynamic after-tax incomes would increase by 4.3 percent in 2022, compared to the 2.1 percent increase in after-tax income on a conventional basis.

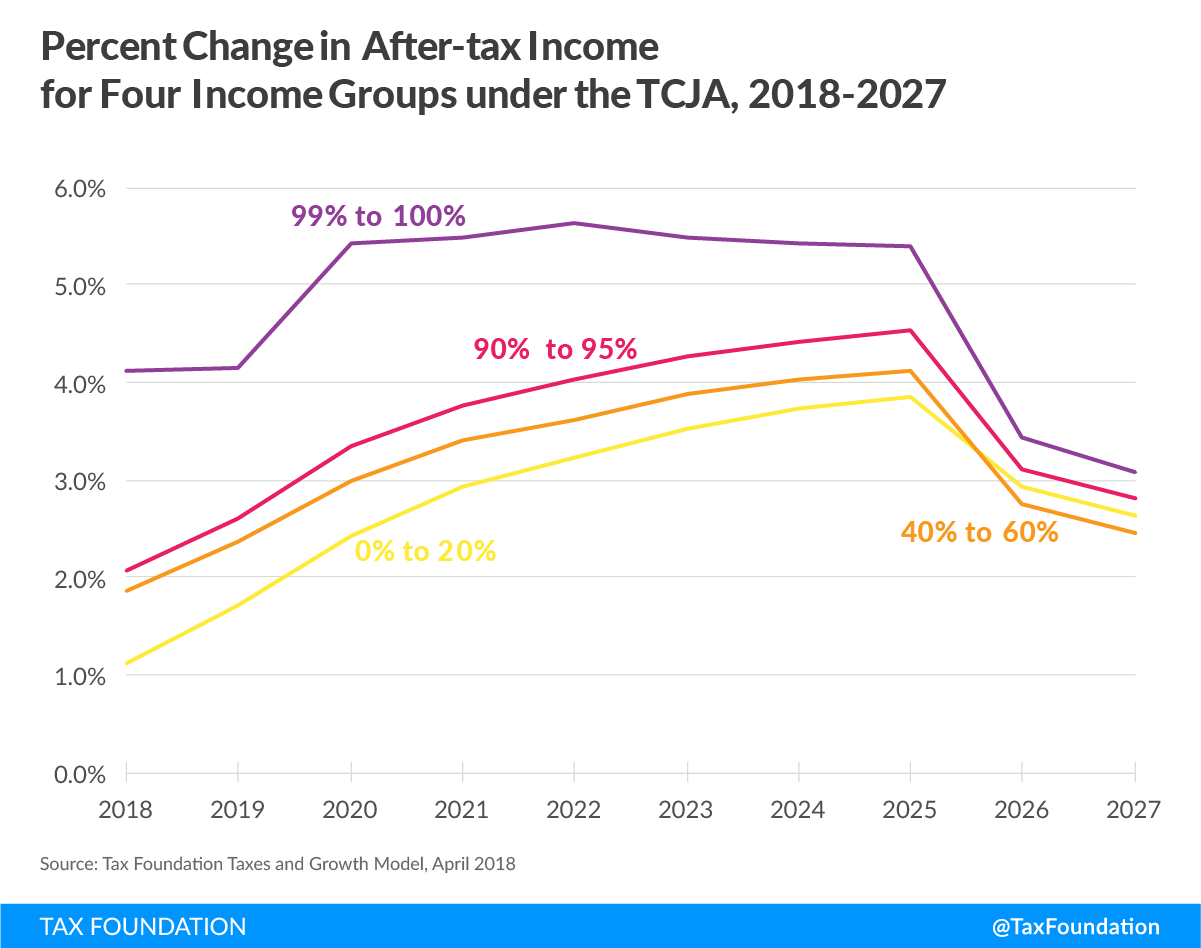

Figure 4.

By 2025, we project after-tax incomes to be meaningfully higher on a dynamic basis than on a conventional basis. In 2025, taxpayer after-tax income peaks at 4.6 percent above baseline for all taxpayers. At this point, we project that GDP will be at its highest point during the decade at about 3 percent over baseline. After-tax income for the bottom 80 percent of taxpayers (those in the bottom four quintiles) will increase by between 3.7 percent and 4.2 percent.

Figure 5.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeEven after the expiration of the individual income tax cuts in 2026 and 2027, after-tax income remains above pre-Tax Cuts and Jobs Act levels, when considering economic growth. In 2027, after the major individual provisions have expired, after-tax income for all taxpayers will be 2.7 percent higher than otherwise. This increase in after-tax income will be due entirely to higher pretax incomes, through economic growth. Tax liability will be slightly higher in 2027 due to the expiration of the individual income tax cuts and the adoption of Chained CPI as an inflation measure.

We project the economy will be about 2.8 percent larger than it otherwise would have been in the absence of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2027.

Overall, the after-tax incomes of taxpayers in most income groups will steadily rise over the next decade on a dynamic basis. Low-, middle-, and upper-middle-income taxpayers will see their after-tax income steadily rise over the decade until 2025. After most individual provisions expire, in both 2026 and 2027, after-tax incomes will still be higher than they otherwise would have been, on a dynamic basis.

Economic Evidence of the Success of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

As noted numerous times already, the economic impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act will take years to fully materialize. Therefore, it is difficult to point to any concrete evidence, as of yet, that an acceleration of economic growth is occurring. Similarly, short-term economic data is noisy; margins of error within the data make trend analysis difficult. Nor does a short-term snapshot indicate the direction of long-run economic trends.[21]

Furthermore, the challenge to any economic analysis is separating out any economic changes occurring simultaneously. For example, since the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the Trump administration has accelerated the imposition of tariffs on imported goods from China and other countries. Erecting trade barriers could counteract the benefits of tax reform, muting any proposed growth.

The Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model can also estimate the impact of the tariffs proposed by the United States and its trading partners. If all the tariffs proposed by the U.S. and its trading partner were enacted, the jobs impact to the U.S. economy would outweigh that of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.[22]

|

Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, April 2018 |

|

| Long-run GDP | -0.60% |

| GDP (Billions of 2018 $) | -$150.60 |

| Wages | -0.38% |

| FTE Jobs | -466,899 |

Thus, it is difficult to say with certainty if any economic results seen since the beginning of 2018 are due to tax reform.

Conclusion

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act improved incentives to work and to invest, which are the factors that drive economic growth. This is why we anticipate the new law to have a positive, long-run effect on the economy.

The Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth model estimates that the total effect of the new tax law will be a 1.7 percent larger economy, leading to 1.5 percent higher wages, a 4.8 percent larger capital stock, and 339,000 additional full-time equivalent jobs.

These are not changes that happen overnight, but changes that will take years to manifest. It is tempting to keep asking that question, “Are we there yet?” The new law improved the competitiveness of U.S. businesses and increased incentives to work and invest in the United States, but these changes do not occur instantaneously. Therefore, it is imperative that we maintain patience and wait for this legislative achievement to boost economic output and wages, and avoid needless speedbumps along the way such as tariffs.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNotes

[1] Scott A. Hodge, “Dynamic ScoringDynamic scoring estimates the effect of tax changes on key economic factors, such as jobs, wages, investment, federal revenue, and GDP. It is a tool policymakers can use to differentiate between tax changes that look similar using conventional scoring but have vastly different effects on economic growth. Made Simple,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 11, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/dynamic-scoring-made-simple/.

[2] Asa Johansson, Christopher Heady, Jens Arnold, Bert Brys, and Laura Vartia, “Tax and Economic Growth,” OECD, July 11, 2008, https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/41000592.pdf. See also William McBride, “What Is the Evidence on Taxes and Growth?” Tax Foundation, Dec. 18, 2012, https://taxfoundation.org/what-evidence-taxes-and-growth.

[3] Scott A. Hodge, “The Corporate Income Tax is Most Harmful for Growth and Wages,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 15, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/corporate-income-tax-most-harmful-growth-and-wages/.

[4] Stephen Entin, “Labor Bears Much of the Cost of the Corporate Tax,” Tax Foundation, October 2017, /wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Tax-Foundation-SR2381.pdf.

[5] Stephen J. Entin, “Disentangling CAP Arguments against Tax Cuts for Capital Formation: Part 2,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 17, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/disentangling-cap-arguments-against-tax-cuts-capital-formation-part-2.

[6] Alan Cole, “Fixing the Corporate Income Tax,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 4, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/fixing-corporate-income-tax.

[7] Stephen J. Entin, “Disentangling CAP Arguments against Tax Cuts for Capital Formation: Part 2.”

[8] Ibid.

[9] Tax Foundation staff, “The Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Model,” Tax Foundation, April 11, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/overview-tax-foundations-taxes-growth-model/.

[10] Tax Foundation staff, “Preliminary Details and Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Dec. 18, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/final-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-details-analysis/.

[11] Erica York, “The Benefits of Cutting the Corporate Income Tax Rate,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 14. 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/benefits-cutting-corporate-income-tax-rate/.

[12] Kyle Pomerleau, “The United States’ Corporate Income Tax Rate is Now More in Line with Those Levied by Other Major Nations,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 12, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/us-corporate-income-tax-more-competitive/.

[13] Scott Greenberg, “What is Depreciation, and Why Was it Mentioned in Sunday Night’s Debate?” Tax Foundation, Oct. 10, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/what-depreciation-and-why-was-it-mentioned-sunday-night-s-debate/.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Scott Greenberg, “Tax Reform Isn’t Done,” Tax Foundation, March 8, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-reform-isnt-done/.

[16] Kyle Pomerleau, “Economic and Budgetary Impact of Temporary Expensing,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 4, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/economic-budgetary-impact-temporary-expensing/.

[17] Erica York and Alex Muresianu, “Reviewing Different Methods of Calculating Tax Compliance Costs,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 21, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/different-methods-calculating-tax-compliance-costs/.

[18] The extension of the Section 199A pass-through deduction would be pro-growth, but arguably, reforms to the deduction’s structure would be more beneficial. For more information, see Scott Greenberg and Nicole Kaeding, “Reforming the Pass-Through Deduction,” Tax Foundation, June 21, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/reforming-pass-through-deduction-199a.

[19] 2018 dollars

[20] Huaqun Li and Kyle Pomerleau, “The Distributional Impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act over the Next Decade,” Tax Foundation, June 28, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/the-distributional-impact-of-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-over-the-next-decade/.

[21] Erica York, “Bureau of Economic Analysis Releases Q2 2018 GDP Estimate,” Tax Foundation, July 27, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/bureau-economic-analysis-releases-q2-2018-gdp-estimate/.

[22] Erica York and Kyle Pomerleau, “Tracking the Economic Impact of U.S. Tariffs and Retaliatory Actions,” Tax Foundation, June 22, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/tracker-economic-impact-tariffs/.

Share