The economy is growing modestly again, in spite of several increases in taxes on saving and investment since 2012. This has led some people to believe that taxing investment does not matter. In fact, the recessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. knocked the economy back to a lower-than-optimal starting point, and the subsequent taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. increases are making it impossible to recapture lost ground. The level of GDP should be much higher at this stage of the recovery. Looking only at the positive movement in GDP while failing to see its depressed level misses key elements of the economics of taxation.

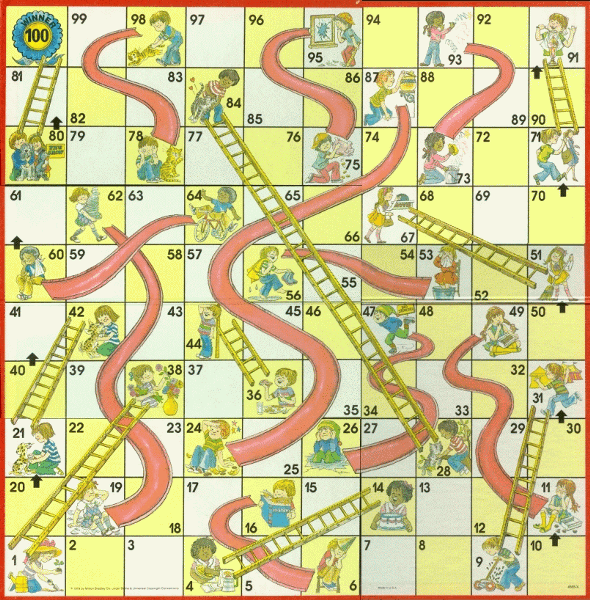

The economics of taxation can be illustrated by the Milton Bradley board game, Chutes and Ladders. The game is played on a board of ten rows of ten squares each. Players march along a row, then back along the next row up, and so on to the hundredth square at the top. Players move forward by spinning a needle that points to a 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 square advance. The average spin is three moves forward each turn.

Here’s the catch. There are chutes and ladders printed on the board that connect squares on different levels. If a player lands at the foot of a ladder, he moves his piece to the top of the ladder, a boost of two to five rows on his march. If he lands at the top of a chute, he slides down two to five rows. After each rise or fall, he resumes plodding upward about three squares a turn, but from a higher or lower starting point. From then on, he will be above his pre-ladder or below his pre-chute level going forward, unless he hits an offsetting chute or ladder to put him back on his old trajectory.

Think of the economy as marching along a path like the players in the Chutes and Ladders game, but with a board of infinite height. The amount of capital and employment has adapted to the current tax and regulatory regime, and the average rate of growth is in line with increases in population and technological progress, with more capital added each year to match the growth in the labor force.

The enactment of tax reductions or regulatory changes that make it possible to profitably employ more capital is like landing on a ladder. These policies induce a burst of capital formation and super-normal economic growth until the additional capital is built up. The added amount of capital per worker raises productivity and wages. Output jumps. Then the economy returns to a normal growth rate, but from a higher level. It will always be ahead of where it would have been without the added capital, as long as the better tax treatment of capital is still in place. (A smaller but similar surge can occur if a tax cut on addition labor income boosts hours worked per worker or raises the labor force participation rate. Once the higher levels are reached, growth resumes in line with the change in the working age population.)

Enacting adverse policies that force a reduction in the amount of capital that people are willing to maintain is like hitting a chute. The economy slows, or even contracts for a period, as the amount of capital that can no longer be profitably employed is shed. Productivity and wages fall. Then growth resumes at its regular pace (in line with the normal growth of population and technology), but from a lower level. Resumption of growth after a bad policy shift does not mean that the policy was harmless, only that the amount of damage was finite. The economy will remain below the level it would have reached without the tax increase on capital income as long as the policy remains in place. (A smaller but similar effect occurs from a rise in the tax on labor; there is a drop in the labor supply, then a resumption of normal increase, but from a lower base.)

There is one major difference between the game of chutes and ladders and the practice of public policy. In the game, the chutes and ladders are predetermined at fixed locations on the board, and landing on one is determined by random chance. In the case of public policy, the chutes and ladders represent changes in tax and regulatory policy; they are created by the Congress, and are determined by politics.

Congress can create growth ladders that raise investment, incomes, and employment by enacting pro-growth tax changes. It can also create anti-growth chutes that reduce investment, employment, and income by imposing higher taxes on saving, investment, and employment. If the game of politics were more focused on growing the economy than on growing the government, we’d encounter more ladders and fewer chutes.

Share this article