As Americans consider their holiday plans, policymakers and economists have been focusing on the state of the U.S. economy and whether the bonanza of consumer spending over the past two years will continue to prop up economic growth into 2024. The uncertain future of American finances in a time of potential economic instability points to the need for taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reforms that encourage individuals to save and build financial security in a relatively simple way, such as through universal savings accounts.

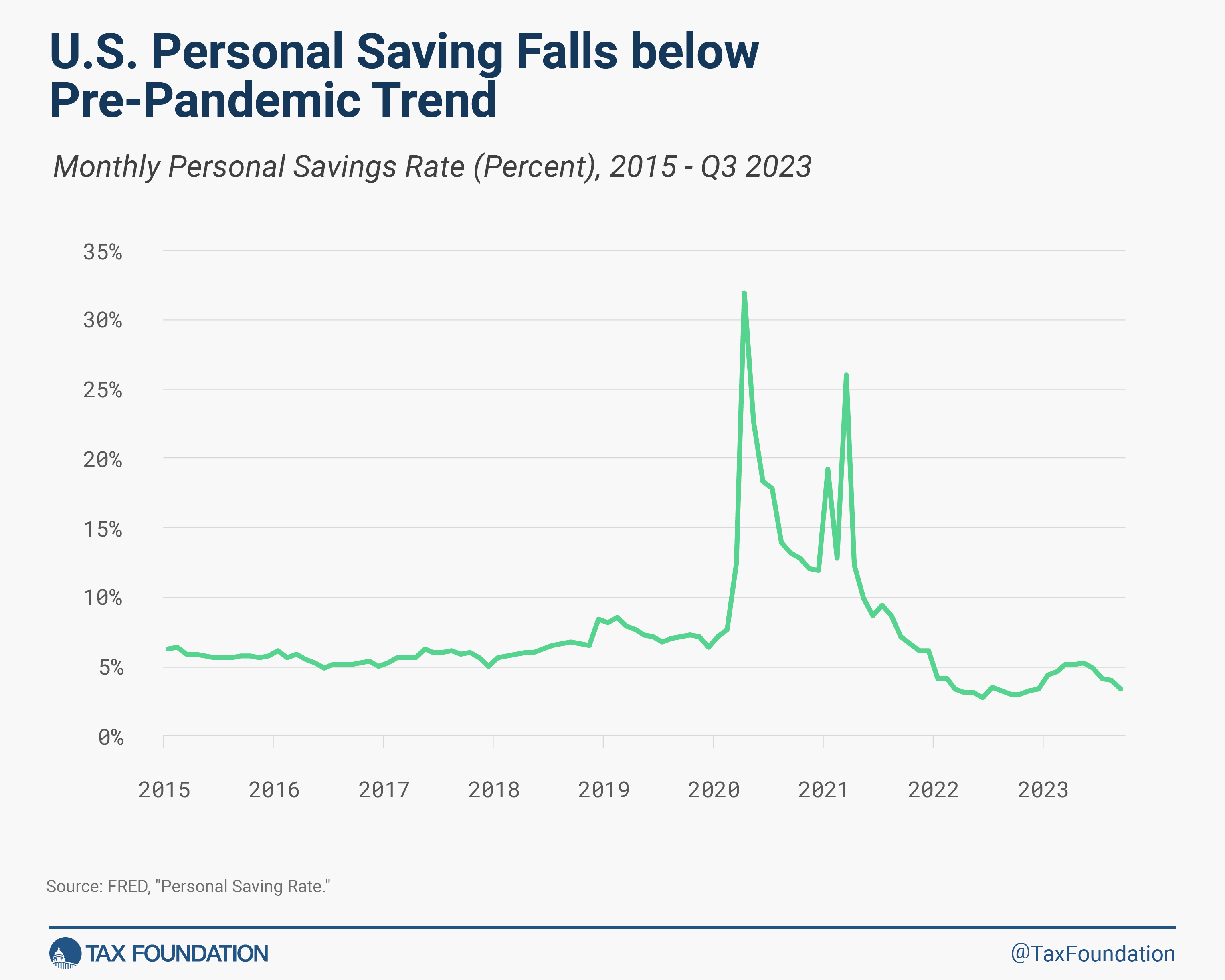

First, what is the state of saving in America? Since 2022, the personal saving rate has fallen significantly after reaching an all-time high during the pandemic. Personal saving spiked at 32 percent in April 2020 as people were encouraged to shelter in place and aid was provided during the onset of the pandemic, but then fell steadily before spiking again in early 2021 due to the Omicron variant.

Saving then fell rapidly as consumers ramped up their spending and began unwinding the cash buffers that had formed from the COVID stimulus spending passed under both the Trump and Biden administrations. The personal saving rate currently stands at 3.4 percent for September 2023, and since 2022, it has been 2.2 percentage points below the 2015 to 2019 average. Compared to other developed countries, the U.S. is an outlier; it is the only country to have its saving rate fall below the pre-pandemic average.

Some evidence indicates the spend-down of savings has contributed to GDP growth over the past three years—if real consumption matched pre-pandemic averages, real GDP would have been about 2 percent lower, according to economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The flood of additional saving during the pandemic also came at a time when American net wealth increased by 37 percent, partly due to the run-up in asset prices as inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. soared.

The latest release of the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances finds that the median household had $8,000 across their savings and checking accounts from 2019 to 2022, an increase of $2,000 compared to the 2016-2019 estimates. Similarly, data from Bank of America suggests that monthly median household savings and checking balances remain about 40 percent higher in nominal terms in September 2023 than in January 2019, with only slight variation across the income spectrum.

While the pandemic may have temporarily boosted American saving, evidence from the Federal Reserve Board surveys suggest that many people would benefit from policies that enable them to save more over the long term.

A Federal Reserve analysis shows remaining excess savings from the pandemic-era stimulus will likely be depleted by the end of the third quarter of 2023, as by June only $190 billion of the $2.1 trillion in total excess savings remained.

Americans are also increasingly relying on credit cards and other forms of debt to bridge the gap in their finances as pandemic saving winds down. In the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED), the Federal Reserve found that the portion of Americans who have emergency savings to cover at least three months of expenses dropped from 59 percent in 2021 to 54 percent in 2022.

American saving was already underwhelming prior to the pandemic, with a middling amount of retirement security compared to other developed countries. The lack of American savings means the U.S. relies increasingly on foreign investment. Our net international investment position (NIIP) stands at about -$18 trillion, meaning that foreigners own about $18 trillion more of American assets than Americans own of foreign assets.

Rather than relying on a temporary spike in saving from the pandemic to fuel the U.S. economy, policymakers should consider reforms, including tax changes, that could sustainably increase saving rates. Increasing American saving would likely require a combination of reforms spanning many areas, including policies to encourage economic growth and mobility.

Tax policy also plays a big role, as shown by the rapid growth and popularity of defined contribution retirement plans like 401Ks, individual retirement accounts (IRAs), and other tax-deferred savings accounts like health savings accounts (HSAs).

The current federal tax code generally discourages saving, since the income tax applies once to wages and again to the return on wages that are saved. By contrast, there is no additional tax on wages that are consumed rather than saved. To make up for this effect, the tax code contains a patchwork of preferences for saving with complicated rules that generally benefit higher-income households (e.g., those who participate in employer-sponsored retirement plans).

Current federal law provides at least 11 different types of tax-preferred saving vehicles, each with a variety of rules and limitations: four main types of retirement saving provisions, three for saving related to education and disabilities, three more for saving related to health and dependent care, and one for saving related to emergencies (a new addition as part of the recently passed Secure 2.0 legislation).

Other countries have found a simpler solution that is more widely available and useful, boosting savings for households across the income scale. Universal savings accounts (USAs) are tax-preferred savings vehicles with unrestricted use of funds, allowing participants to save for a variety of reasons including retirement, education, housing, health, unemployment, and emergencies.

For example, Canada provides Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs) to anyone 18 or older with an annual contribution limit of CAD 6,500 (about $4,700), and any unused contributions from one year can be carried forward to the next year. Contributions are made with after-tax dollars, earnings grow tax-free, and withdrawals can be made at any time for any reason without penalty. The United Kingdom provides Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs) with an annual contribution limit of GBP 20,000 (about $25,000), and contributions are also made with after-tax dollars and earnings grow tax-free.

Both programs are used widely across the income spectrum. For example, TFSAs are used by more than half of Canadians. The accounts, first adopted in 2009, have quickly become more popular than tax-preferred retirement accounts, resulting in an overall increase in participation and average contributions in registered savings accounts, particularly among low-income households.

While policymakers in Congress have introduced limited USAs, a broader overhaul of the tax treatment of saving may be in order as part of fundamental tax reform. As luck would have it, such an opportunity arises at the end of 2025 when individual provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act expire. Policymakers should use the opportunity to simplify the tax system and encourage saving with the goal of building financial security for low- and middle-income households.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe