Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards (D) released details of a proposed taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. plan a few weeks ago, which my colleague Nicole Kaeding covered here. Since then, some new details have emerged, but the main thrust of the plan is an attempt to remove the recent sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. increase (the famed “clean penny” that wasn’t so clean in effect), and pay for it with a gross receipts tax. The full details include almost a dozen moving parts:

- Individual Income Taxes: The plan would lower the current individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rates from 2, 4, and 6 percent to 1, 3, and 5 percent, contingent on a repeal of the deduction for federal taxes paid (which would be a constitutional amendment requiring voter approval).

- Corporate Income Taxes: The plan would consolidate the state’s five corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. brackets of 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 percent into three brackets of 3, 5, and 7 percent, also contingent on a repeal of the deduction for federal taxes paid (again, requiring a constitutional amendment/voter approval).

- Sales tax: The 1-cent sales tax increase passed in 2016 would expire as planned at the end of the 2018 fiscal year. The state would expand its sales tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. to include a number of services, mirroring the tax base of neighboring Texas. The state would also unify the sales tax bases of the remaining 4-cent, state-level sales tax to local sales tax structures (which virtually every other state already does).

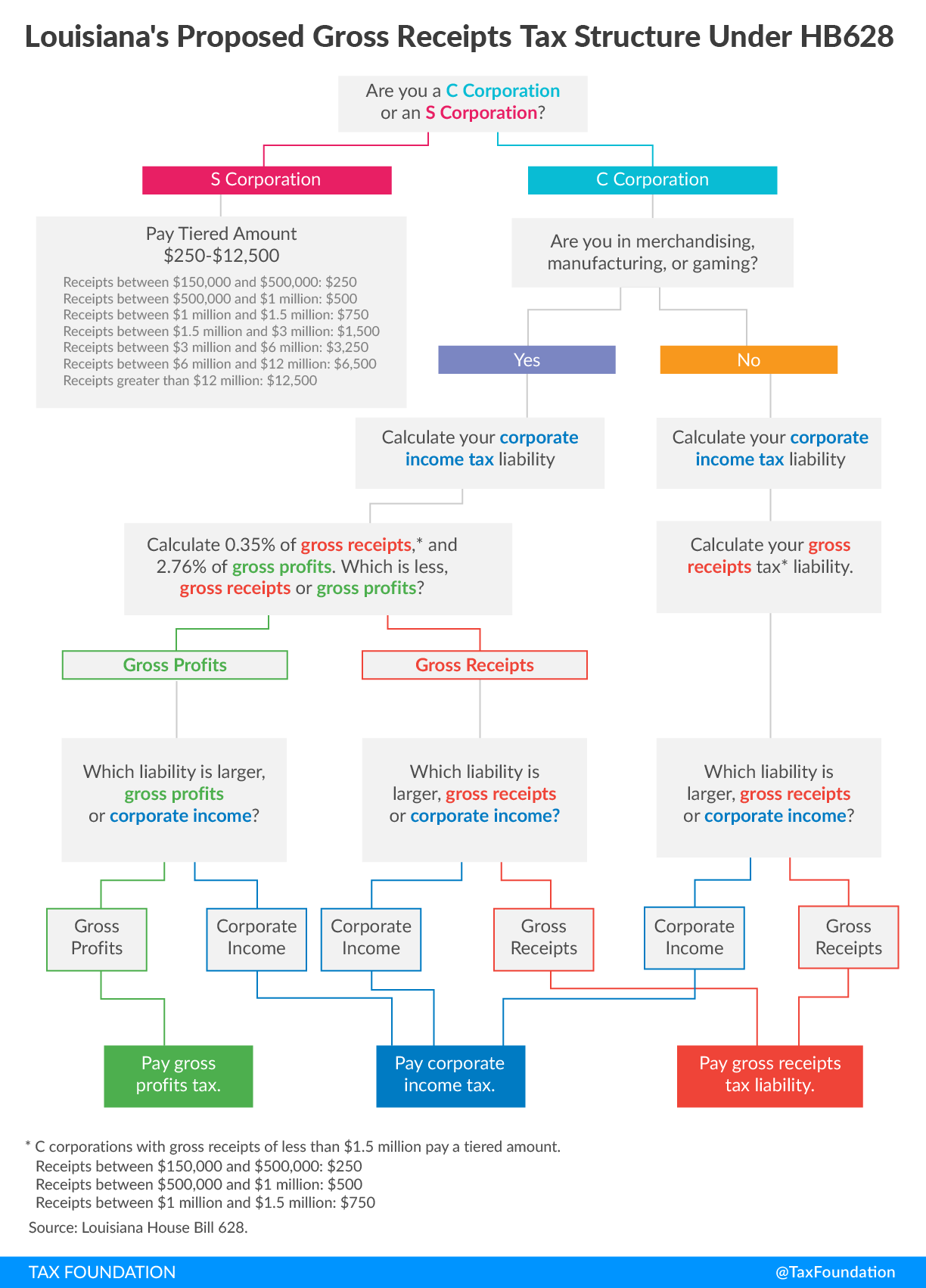

- Gross Receipts TaxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. : Governor Edwards proposes to create a new gross receipts tax. The tax, set at 0.35 percent of receipts above $1.5 million, would serve as a minimum tax to the corporate income tax. The plan has been dubbed the “Commercial Activity Tax,” a name used by Ohio to describe its gross receipts tax, but Louisiana’s structure would be notably different than the Ohio CAT. In recent days, more details of this plan have emerged, and the structure is quite complex, with labyrinthian rules for pass-throughs, regular C-corporations, and manufacturing C-corps. See Jason DeCuir’s summary here.

- Franchise Tax: The state’s franchise tax would phase out over the next 10 years.

Over the last two years, Louisiana has commissioned studies, convened task forces, and hosted extensive legislative conversations about ways for the state to accomplish comprehensive tax reform. The governor’s plan is far-reaching, and touches on every major tax type in an attempt to improve the state’s tax structure, but I believe it fails in that regard for some really important reasons.

First, all of the bad things in the plan take effect immediately, while all the promised positive changes are unlikely to occur due to extended phase-in times or constitutional hurdles. There is a very real possibility that all that could be accomplished under this plan is a new gross receipts tax, a reduction in the sales tax (which is scheduled to happen anyway), and a franchise tax that is reduced mildly for one or two years, and then halted.

Second, the introduction of a gross receipts tax is a nonstarter. The proposal is markedly out of line with public finance literature, and was not included in the recommendations of either the 2017 blue ribbon task force on fiscal reform, the 2015 commissioned report of economists Richardson, Sheffrin, and Alm, or the 2016 recommendations of the Tax Foundation.

Though all gross receipts taxes are undesirable due to the phenomenon they create called “tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action. ,” or taxes on taxes, the structure of this gross receipts tax proposal is uniquely complex in its administration and calculation. The plan has a different tax calculation depending on whether a firm is a pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. , a C-corporation, or a C-corporation manufacturer; and your tax burden is a result of a different branch on a decision tree for each firm type. My colleague Nicole Kaeding put together this dizzying graphic:

One of the most notable oddities is that in the case of manufacturers, the taxpayer pays the greater of three tax bases, where one of those three is the lesser of two other tax bases. Another way to think about the base for C-corp manufacturers is that it is a value-added tax, inside a gross receipts tax, inside a corporate income tax. I haven’t seen a tax quite so unique in its application of various minimums and maximums to try to achieve a result of higher tax burdens.

What Louisiana needs is fewer taxes with broader bases and lower rates, not more taxes with narrow bases and choose-your-own-adventure tax calculations.

Be sure to read our comprehensive study on Louisiana’s tax system here.

Share this article