Late last week, President Joe Biden released a piece reviewing his tax proposals, contrasting them with President Donald Trump’s tax ideas. A major theme within this piece can be summarized in the title: “A Tale of Two TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Policies: Trump Rewards Wealth, Biden Rewards Work.”

Biden raises an important question regarding how work (referring to labor income) and wealth—that is, returns from capital investments such as capital gains and dividends—should be taxed. While “taxing wealth like work” may be an effective campaign tagline, it glosses over that the current tax treatment of capital income is the product of difficult trade-offs related to neutrality, economic efficiency, administrability, and the way we tax C corporations in the U.S.

A major component within the federal tax code is the preferential income tax rate for qualified dividends and long-term capital gains (that is, gains held for over one year). Under current law, these sources of capital income are taxed at preferential rates, with a top rate of 23.8 percent when including the net investment income tax (NIIT). Some argue that the preferential rates are unfair, as labor income is taxed at higher levels in our progressive income tax system, up to 37 percent.

Additionally, owners of assets with accrued capital gains can defer paying capital gains tax until the gain is realized, or even avoid the tax altogether when bequeathing the asset to an heir through step-up in basis. Critics of this tax treatment argue that this leads to lower effective tax rates for the highest earners, as economists Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez argued in their book The Triumph of Injustice last year. This perceived unfairness has motivated several of Biden’s tax proposals, including his idea to tax capital gains as ordinary income for those earning over $1 million and repealing step-up in basis.

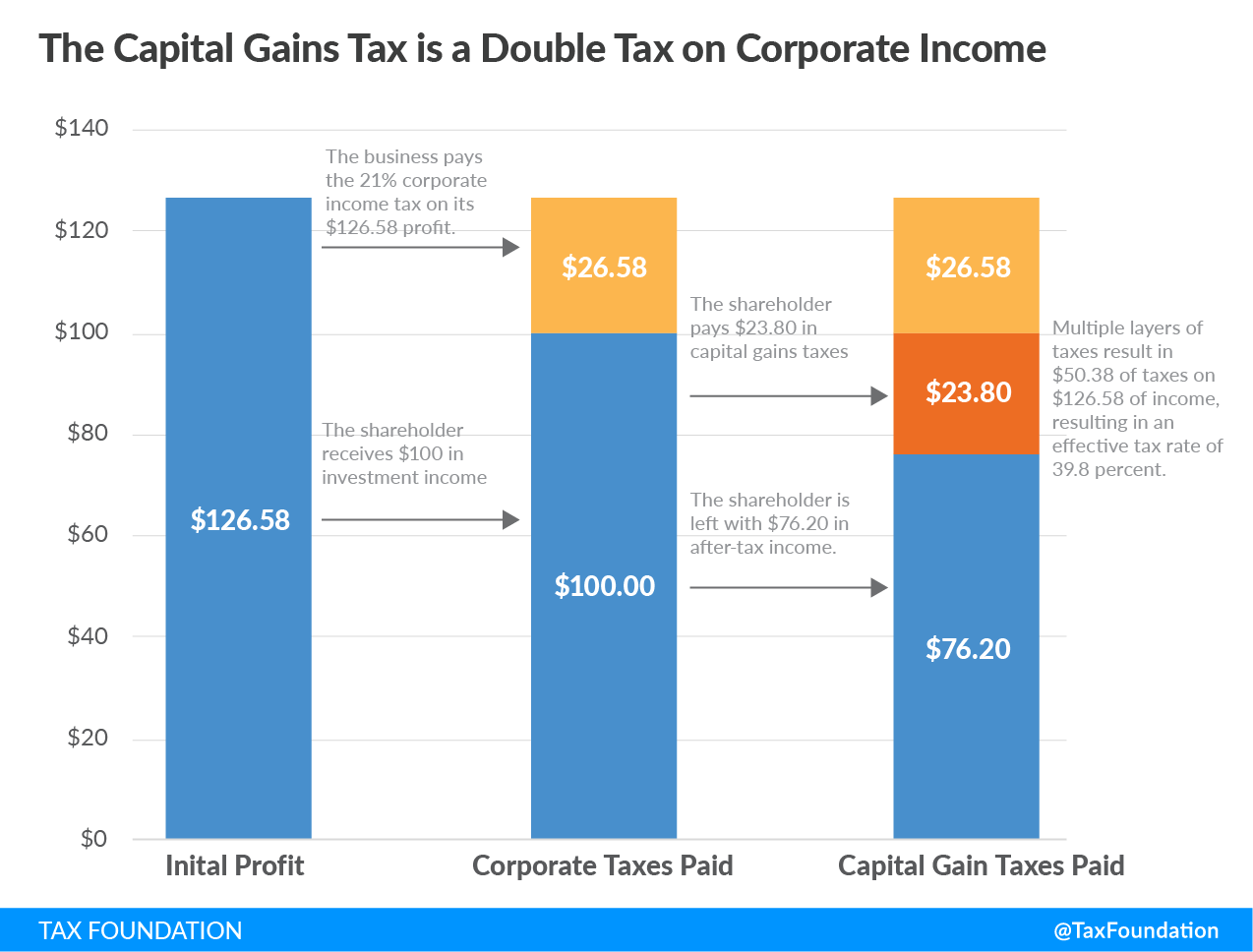

The preferential tax rates for qualified capital gains and dividends exist in part to mitigate the double taxation of returns to corporate equities, which are taxed once at the firm level at 21 percent before being taxed again when shareholders receive corporate dividends or realize a capital gain (see Figure 1). Additionally, returns to saving are not taxed neutrally, as both the principal and returns are taxed. This incentivizes consumption over saving (deferring consumption), reducing investment and incomes. This is especially true for the pass-through sector, which may not have as much access to international capital markets to make up for reduced domestic saving.

Finally, deferral for capital gains has a strong administrability rationale, as taxing gains as they accrue is fraught with many challenges, including how to treat losses and value illiquid sources of returns. A mark-to-market system would help reduce the lock-in effect as investors could no longer avoid taxable events, but at the trade-off of reduced national income and higher administrative costs.

While preferential tax rates for investment income can help mitigate double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. , they create opportunities for tax avoidance if taxpayers have opportunities to reclassify labor income taxed at the ordinary rate into capital income taxed at preferential rates.

Income earned through wages and salaries is a straightforward example of labor income, and it is difficult to find ways to reclassify this income to get a preferential tax rate. However, income earned by self-employed individuals can be harder to judge, as that income may include both a labor and capital component. Entrepreneurs, for example, “working for themselves,” are both earning labor income and generating profits—capital income—at the same time.

There are many rules within the tax code to govern how, for instance, S corporationAn S corporation is a business entity which elects to pass business income and losses through to its shareholders. The shareholders are then responsible for paying individual income taxes on this income. Unlike subchapter C corporations, an S corporation (S corp) is not subject to the corporate income tax (CIT). owners divide their income into a salary subject to ordinary rates and business profits subject to lower rates. However, enforcement of these rules is challenging and there are vigorous debates about how to treat certain income sources, such as carried interest.

Additionally, new research suggests that human capital possessed by owners drives much of the business profit earned by pass-through firms, which means that returns to pass-through firms are not merely the product of financial capital (complicating both how to tax pass-through firms and measure inequality).

These issues show that taxing capital income and labor income similarly is a difficult goal to achieve and comes with real trade-offs that policymakers have to consider when proposing tax changes. There are opportunities to reduce avoidance incentives in the tax code, fortunately, by ensuring that effective tax rates between business forms and sources of financing are as neutral as they can be, in addition to shoring up rules related to self-employment taxes. Biden’s tax plan, however, would go the other direction by increasing the bias in favor of debt-financing and non-corporate investment.

Foundational tax reforms could simplify the business tax system too. A business cash-flow tax assessed across all business forms, for example, would ensure that the tax system does not discriminate based on business type or types of investment.

Short of a deeper reform, however, policymakers and political candidates must consider how the trade-offs and avoidance opportunities change when modifying the taxation of wealth and work.

Share this article