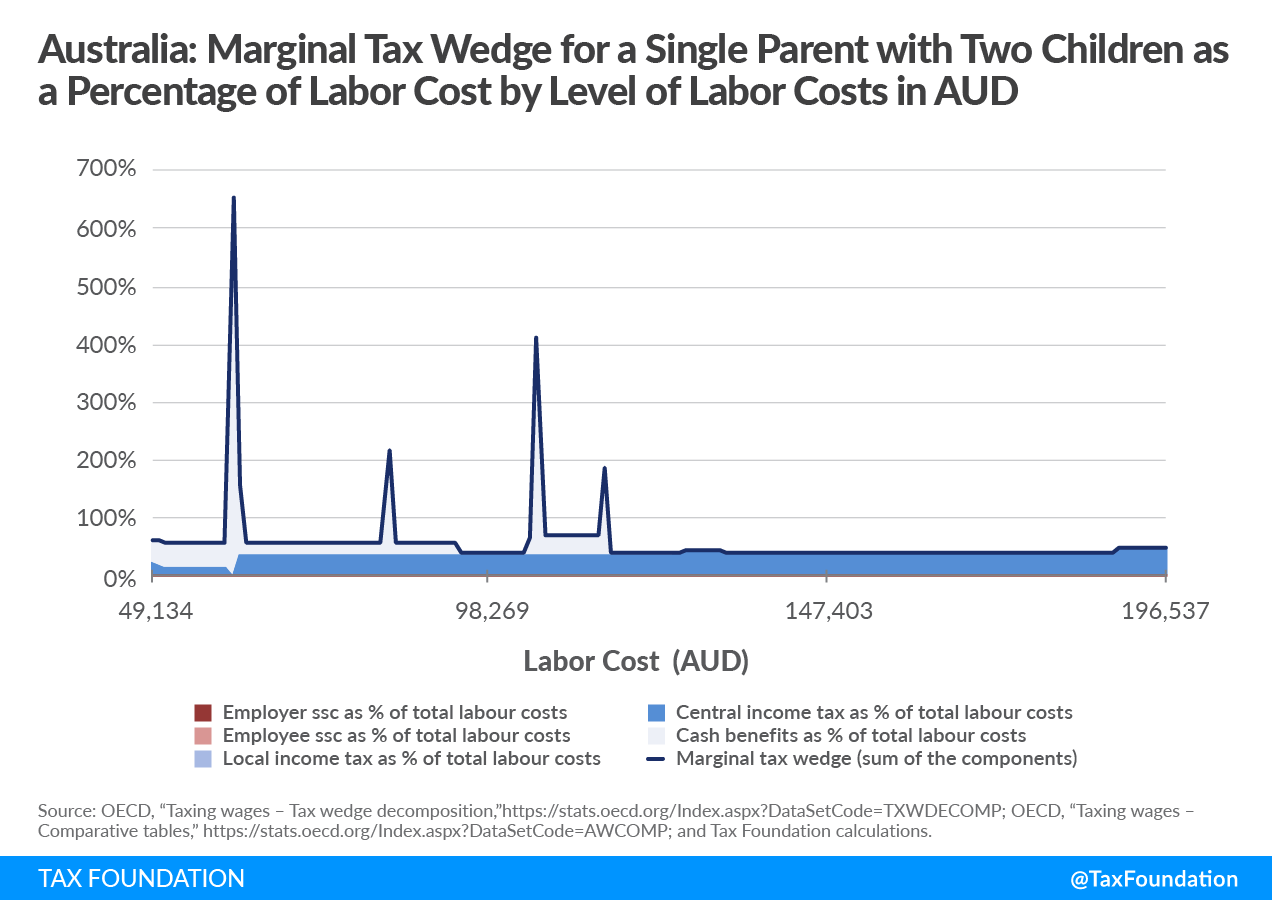

Imagine that a government provides subsidies to single parents that actually increase taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rates on additional work. This is the case for an Australian single parent who earns less than the average wage. With an increase in pay of just AUD 983 more, he would face a 652 percent marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. . Therefore, despite the pay increase, this worker will face a net loss and see his earnings cut by AUD 5,428. An Australian parent who benefits from a government program worth AUD 21,000 might lose 100 percent of that benefit if he or she earns above the earnings threshold.

This is why the marginal tax wedgeA tax wedge is the difference between total labor costs to the employer and the corresponding net take-home pay of the employee. It is also an economic term that refers to the economic inefficiency resulting from taxes. is relevant for understanding how workers might benefit (or not) from an increase in pay once taxes enter the picture.

While the Australia tax and benefit system can be successful in keeping low-income working households out of poverty and encouraging workforce participation, high marginal tax rates like the one observed in the case of this Australian working parent act as barriers to upward mobility, discouraging parents from advancing in their careers. Very often these high rates are hidden in complex tax structures. However, a recently published study by Archbridge Institute and Tax Foundation highlights the underlying policies that drive the marginal tax rate spikes that workers are subject to in a number of countries.

| Australian Single Worker with Two Children Average Labor Cost: AUD 98,269 (US$65,689) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Labor Cost | AUD 60,927 | AUD 83,528 | AUD 105,147 | AUD 114,974 |

| Net Earnings Before the Raise | AUD 71,249 | AUD 74,071 | AUD 83,323 | AUD 82,990 |

| Amount of the Raise | AUD 983 | AUD 983 | AUD 983 | AUD 983 |

| Amount of Additional Tax/Benefits Reduction Due to the Raise | AUD 6,410 | AUD 2,120 | AUD 4,045 | AUD 1,842 |

| % of the Raise Eaten up by the MTR | 652.31% | 215.77% | 411.60% | 187.40% |

| Net Earnings After the Raise | AUD 65,821 | AUD 72,934 | AUD 80,261 | AUD 82,131 |

| Source: OECD, “Taxing wages – Tax wedge decomposition,” https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TXWDECOMP; OECD, “Taxing wages – Comparative tables,” https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=AWCOMP; and Tax Foundation calculations. | ||||

When moving up the income ladder an Australian worker with children can face tax rate spikes of over 100 percent at four different points due to the Family Tax Benefit and the Parenting Payment Single.

In 2021, the first marginal tax rate spike occurred at 62 percent of the average wage and approximately 73 percent of the median wage. If the employer of this Australian worker increased compensation by just AUD 983, the worker faced a net loss and saw his earnings cut by AUD 5,428. This Australian parent faced a marginal tax wedge of 652 percent for a 1 percent increase in gross earnings on top of the gross annual wage of AUD 57,854. This is due to the clawback of the Parenting Payment income support that single parents in Australia are entitled to. For a single parent with two children, the income limit to access the Parenting Payment is reached at this level of income.

Moving up the income ladder this worker faced a marginal tax wedge of 216 percent for a 1 percent increase in gross earnings on top of the gross annual wage of AUD 79,316. This Australian single parent faced a net loss and saw his earnings cut by AUD 1,138. This is due to the Family Tax Benefit, Part A, as for the year 2020-21 a year-end supplement of AUD 781.1 per child was made available for parents with a taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. under AUD 80,000.

Moving one step up the income ladder this Australian worker faced a marginal tax wedge of 412 percent for a 1 percent increase in gross earnings on top of the gross annual wage of AUD 99,845. Therefore, despite the AUD 983 pay increase, this Australian worker faced a net loss and saw his earnings cut by AUD 3,062. This is due to the Family Tax Benefit, Part B (AUD 3,314.2 and a one-off supplement of AUD 379.6), which ends when the taxable income reaches AUD 100,000.

Moving higher up the income ladder this Australian single parent faced a marginal tax wedge of 187 percent for a 1 percent increase in gross earnings on top of the gross annual wage of AUD 109,176. This is due to the Family Tax Benefit Part A that phases out completely at this level of taxable income.

Previous research analyzing the marginal tax rates in Australia has shown that the design of income support payments generates effective marginal tax rates of over 69 percent in the case of a jobless couple with two children if one member of the couple secures a full-time job with a low wage. Even though the system has been reformed since that research was published, confiscatory marginal tax rates of over 100 percent, also called “income traps,” can still be observed.

The tax and benefit system in Australia is extremely complex with numerous thresholds and different types of benefits depending on workers’ taxable income and children’s age. Additionally, the existence of different tax benefits for single parents and one-earner and two-earner couples generates a series of marginal tax rates that might keep some workers in Australia just below the threshold earnings that trigger the tax rate spikes. Eliminating these barriers by implementing a more homogenous tax and benefit system will allow workers to have access to higher wages without confronting these barriers.

Learning from Finland

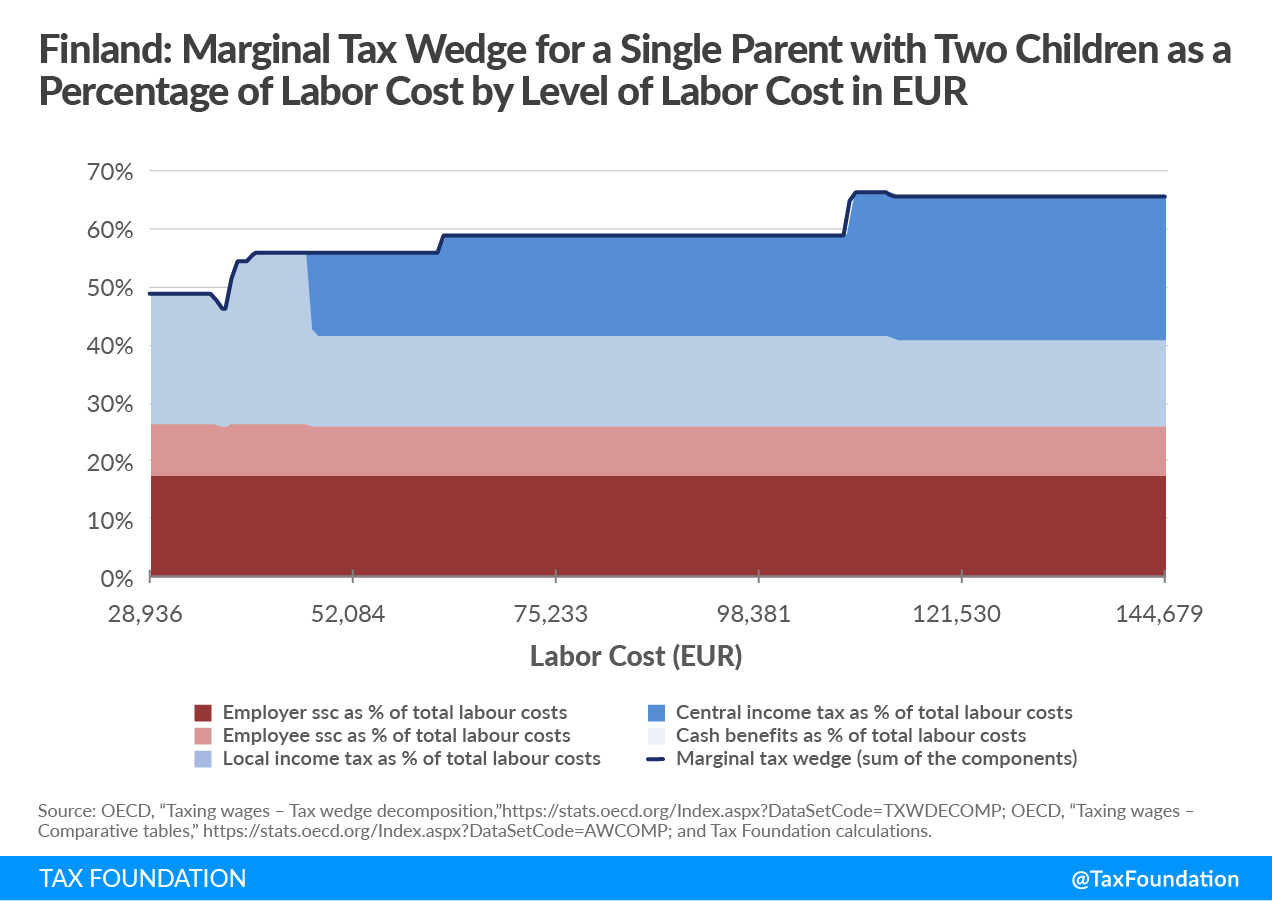

Australia could follow the example of Finland, where a single parent with two children faces a progressive marginal tax wedge profile, starting at 49 percent up to 65.7 percent, and no marginal tax rate spikes can be observed. The increase in the marginal tax wedge rate in Finland is due to a progressive central income tax, while social security contributions have a flat rate. Finland also offers a fixed child allowance independent of taxable income that prevents the formation of marginal tax rate spikes like the ones observed in Australia. Nevertheless, marginal tax rates above 50 percent as the ones observed both in Australia and Finland, especially for workers earning less than the average wage, might discourage employment and labor supply. Even if marginal rates do not spike in a way that traps people in poverty, high marginal rates still impact workers directly.

The loss in benefits that especially poor Australian single parents face when taking on additional work hours can deter them from advancing in their careers, showing that the tax-benefit system, although successful in keeping low-income working households out of poverty, is inefficient in promoting upward mobility of single parents. The Australian tax and benefit system comes with trade-offs that policymakers must keep in mind when planning to reform the tax policy. In Australia two of the marginal tax rate spikes directly impact single parents earning less than the average wage. Therefore, reshaping some of these policies to generate a smoother variation of marginal tax rates over different income levels would likely raise labor supply and encourage the upward mobility of Australian low-income single parents.

Note: This is part of a five-part blog series that highlights the findings of a recently published study by Archbridge Institute and Tax Foundation and explores the underlying policies that drive the marginal tax rate spikes that workers are subject to in a number of countries.