Download Special Report No. 176

More States Considering Affiliate Nexus TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Despite Failures in Other States

Special Report No. 176

Executive Summary

Citing significant budget shortfalls and the inability to collect sales taxes on many Internet-based transactions, a number of states are considering the adoption of “Amazon taxes.” Such laws, nicknamed after their most visible target, require retailers that have contracts with “affiliates”—independent persons within the state who post a link to an out-of-state business on their website and get a share of revenues from the out-of-state business—to collect the state’s sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding.

.

Contrary to the claims of supporters, Amazon taxes do not provide easy revenue. In fact, the nation’s first few Amazon taxes have not produced any revenue at all, and there is some evidence of lost revenue. For instance, Rhode Island has seen no additional sales tax revenue from its Amazon tax, and because Amazon reacted by discontinuing its affiliate program, Rhode Islanders are earning less income and paying less income tax.

Amazon taxes also do not “level the playing field” between brick-and-mortar and online businesses; the laws actually mandate disparate burdens on online businesses. Litigation over the constitutionality of Amazon taxes is ongoing, with scholars on the left and right disputing their wisdom and legality.

Enacting an Amazon tax law also sends a signal of hostility to businesses engaged in interstate commerce, runs the serious risk of retaliation from other states and from affected businesses, and undermines efforts to improve the uniformity of state sales taxes.

Key Findings

- Frustrated by their inability to impose tax collection obligations on companies with no substantial connection to their state, several states are considering the adoption of “Amazon” tax laws. Such laws currently exist in New York, Rhode Island, North Carolina, and Colorado.

- An Amazon tax law requires retailers that have contracts with “affiliates”-independent persons within the state who post a link to an out-of-state business on their website and get a share of revenues from the out-of-state business-to collect the state’s sales and use tax.

- Amazon taxes are unlikely to produce revenue in the near term. New York continues to face a lengthy legal constitutional challenge. Rhode Island has even seen a drop in income tax collections due to the law.

- Amazon taxes do not level the playing field between brick-and-mortar and Internet-based businesses because they require Internet-based businesses to track thousands of sales tax bases and rates while brick-and-mortar businesses need to track only one.

- Unconstitutionally expansive nexus standards like the Amazon tax undermine legal certainty, burden interstate commerce, and harm economic growth.

State Tax Officials Frustrated Over Limited Powers to Collect Sales and Use Taxes

Enactment of an Amazon tax is an aggressive and unwise assertion of state power to collect taxes from out-of-state businesses. These taxes represent the latest in a series of efforts to eliminate the long-standing “physical presence” standard and replace it with a nebulous, arbitrary standard of “economic presence,” where businesses can be taxed in every state where they have customers.

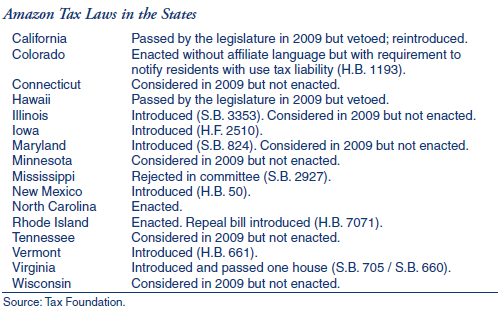

Table 1

After a wave of sales tax adoptions in the 1930s, states became concerned that consumers would escape the tax by purchasing goods and services in other states. States with sales taxes began adopting “use” taxes, which impose a tax on the use within a state of an item upon which a sales tax has not been paid. Thus, states with less competitive tax systems than their neighbors sought to tax transactions occurring in other states to equalize tax burdens — essentially a protectionist measure.

In 1937, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of use taxes so long as they were nondiscriminatory and “compensating” — that is, designed to equalize taxes on both locally produced and imported goods.2 However, states must collect the use taxes from residents directly, because subsequent judicial decisions set limits on the state’s power to require companies to collect sales taxes. Only those companies with a significant connection (“nexus”) with the state, meaning the physical presence of either property or employees in the state, can be required to collect sales taxes for the state.3 These decisions have been premised both on the geographic limit of state powers and on the difficulty of complying with thousands of ever-changing state sales tax bases, rates, and exemptions.4

State tax administrators and champions of higher state spending are displeased with this status quo. They know from political and administrative experience that use taxes are practically unenforceable, and the only other way to get the revenue — forcing out-of-state companies to collect the taxes — has been severely limited. Brick-and-mortar retailers have also claimed unfairness at their having to collect sales tax while their online and out-of-state competitors escape the same obligation. Of course, the proposal on the table is to impose a greater obligation on out-of-state and Internet companies: force them to collect thousands of different sales taxes, while brick-and-mortar retailers need to track only one.5

Several dozen states have banded together to form the Streamlined Sales Tax Project (SSTP), an effort to simplify and harmonize state sales taxes in the hope that Congress or the Supreme Court will permit states to enforce use tax collection obligations on out-of-state companies.6 While the SSTP has made notable progress on adopting uniform sales tax definitions and procedures, meaningful efforts to simplify sales taxes (such as by reducing the number of sales taxing jurisdictions or aligning them with zip codes) have been actively avoided in the hopes of attracting more members.7

Figure 1

“Amazon Taxes” as of March 2010

Frustrated by revenue demands and the slow pace of progress at the SSTP, a few states have turned to Amazon laws. SSTP officials — even those critical of the physical presence rule — oppose the Amazon tax effort, arguing that such laws are unwise, unconstitutional, or both.8

Four States Enact Amazon Tax Laws; Several Considering

Frustrated by its residents who purchase items online but do not pay the sales or use tax they owe, New York targeted online retailers with only the slightest connection to New York by enacting what has become known as an “Amazon tax” in April 2008. It is designed to force online retailers like Amazon.com to collect New York sales tax on purchases made by New Yorkers, even though Amazon has no property or employees in New York. The law requires retailers that have contracts with “affiliates” — independent persons within the state who post a link to Amazon.com on their website and get a share of revenues — to collect New York sales tax.

In 2009, Rhode Island and North Carolina enacted Amazon tax laws. Colorado followed in 2010 with a version that removed language asserting that affiliates trigger the obligation to collect sales tax but that added a requirement to notify residents with use tax liability.9 The legislatures of California and Hawaii also passed Amazon tax laws, but they were vetoed by their respective governors in 2009.10 In 2010, Mississippi rejected an effort to enact an Amazon tax law but other states are considering legislation (See Table 1). The Governor of Nevada has also proposed an Amazon tax.11 Additionally, a bill is pending in Rhode Island to repeal its Amazon tax law.12

Common language from the bills includes:

A person with no physical presence in the state is presumed to be engaging in business in the state if:

-

1.that person enters into an agreement with an in-state resident under which the resident, for a commission or other consideration, directly or indirectly refers potential customers, whether by link or an Internet web site, to that person; and

2.the cumulative gross receipts from sales by that person attributable to referred customers by all residents with such an agreement are greater than $10,000 during the preceding 12-month period.

The nexus presumption would be rebuttable by proof that the resident made no solicitation in the state that would satisfy U.S. constitutional nexus requirements on behalf of the person presumed to be engaging in business in the state.

Amazon Taxes Do Not Result in a Revenue Windfall; Revenue Drop More Likely

Sponsors have promised that a revenue windfall would follow enactment of an Amazon tax, but no windfalls have been forthcoming so far. This is often because online companies respond to Amazon tax law enactments by ending their affiliate programs. Rhode Island revenue-analysis office head Paul Dion stated in December 2009 that the six-month-old law had collected no revenue.13 An affiliate trade group believes that Rhode Island has seen less tax revenue come in, because the elimination of the affiliate program reduced income and thus income tax collections.14 State Treasurer Frank Caprio echoed this, saying, “The affiliate tax has hurt Rhode Island businesses and stifled their growth, as they’ve been shut out of some of the world’s largest marketplaces, and should be repealed immediately.”15

Similarly, legislative officials estimated that North Carolina’s Amazon tax would raise $13 million in its first year of operation, but the termination of affiliate programs in the state makes this unlikely. Revenue officials have stated that they are not tracking Amazon tax revenues.16

New York is collecting tax revenue but under a constitutional cloud, making it risky to spend it.

The fiscal note attached to the Virginia bill soberly explains why revenue windfalls are unlikely from Amazon taxes, and why they can actually reduce state revenues:

When similar legislation was enacted in Rhode Island and North Carolina, large online retailers ended their affiliate programs. If this were to happen as a result of this bill, there would be no additional revenue from the enactment of this bill. In fact, by ending the affiliate program with Virginia vendors, such vendors would likely lose business and remit less Retail Sales and Use Tax to Virginia. Ending affiliate agreements in Virginia would also reduce or eliminate the commissions and profit that the affiliates receive from these agreements. Although there is only very limited publicly available data, the reduction or elimination of such commissions and profits would likely have a negative impact on those businesses’ profits.17

Even a prominent supporter of Amazon tax laws has conceded that they will not generate revenue for immediate budget needs. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) Senior Fellow Michael Mazerov, author of a paper18 encouraging states to adopt Amazon tax laws, conceded during a panel in early February 2010 that the laws will not raise revenue in the short term.19 (Mazerov argues that there are long-term benefits to the approach.)

New York Mired in Litigation Over Amazon Tax Law’s Constitutionality

In New York, Amazon.com challenged the law as violating the U.S. Constitution, arguing that they have no property or employees in New York and thus cannot constitutionally be required by the state to collect its taxes. The case is currently on appeal to New York’s intermediate court, the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division.20 (New York’s highest court is called the Court of Appeal; the trial-level court is the New York Supreme Court.)

New York relied on two U.S. Supreme Court cases, Scripto, Inc. v. Carson and Tyler Pipe Indus. v. Washington Dep’t of Revenue, where in-state independent persons were so necessary and significant in establishing and maintaining the out-of-state company’s market in the state that the companies were deemed to be present in the state.21 These “attributional nexus” cases have been described by the Supreme Court itself as the “furthest extension” of nexus.

The trial court, in finding for the state and upholding the law, did not consider how significant the affiliates were in establishing or maintaining Amazon.com’s New York market; instead they simply held that Amazon.com gained economic benefits and thus nexus was established.22 Whether Amazon.com gains economic benefits is the test for employees, not for independent persons. The trial court thus confused two unrelated tests and therefore reached the wrong conclusion.

New York’s law is an unprecedented expansion of state taxing authority. The affiliates provide referrals for only 1.5 percent of Amazon.com’s sales in New York, and there is no evidence that the affiliates even target New Yorkers (they operate via websites, available worldwide). The affiliates neither engage in direct solicitation nor provide any crucial sales support for Amazon.com in the state. At minimum a court must find that the affiliates are essential for Amazon.com’s market in the state before deeming the out-of-state company to be “present” in the state under even Scripto and Tyler Pipe.

In the Quill case of 1992, the Supreme Court struck down a 1987 North Dakota law imposing a tax collection obligation on mail-order businesses, where the threshold was $1 million of in-state sales. By contrast, New York’s law applies to businesses with just $10,000 in in-state sales. Adjusting for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. and population, the $1 million threshold in North Dakota that the U.S. Supreme Court found low enough to pose an intolerable burden in 1987 would be the equivalent of $51 million in New York in 2009, and yet New York still set its Amazon threshold at a mere $10,000.

The trial court also claimed that Amazon.com is “avoiding” taxes.23 This is not true; the taxes are owed by New Yorkers purchasing items online. Under the New York law, Amazon.com would collect these taxes, but the dollars would be paid by New York consumers. (The burdens of collection, however, would be imposed on Amazon.com.)

The appellate court is expected to reach a decision sometime in 2010.

Far from Leveling the Playing Field, Amazon Taxes Unlevel It

Amazon tax supporters often claim that the current tax environment is unfair to brick-and-mortar businesses in that they must collect sales tax on their sales while Internet-based businesses do not. Consequently, the Amazon tax is urged as a way to equalize this disparate treatment.

Far from creating a level playing field, Amazon taxes move away from one. Brick-and-mortar businesses collect sales tax based on where the business is located, so they need to track only one sales tax rate and base. Under Amazon taxes, though, out-of-state businesses are required to collect sales tax based on where the customer is located. Thus, each retailer no matter how large or small must track 8,000+ sales tax rates and bases. Further, these constantly change and (contrary to common assumptions) are not aligned with even 5-digit zip codes, let alone 9-digit zip codes.

Various databases exist to assist with figuring sales tax but they are often expensive, not comprehensive, and can be slow to keep up to date. Some states offer websites with sales tax “maps” but these are not widespread and do not address which items are in the base. These shortcomings are particularly problematic for sales taxes, since under-collecting can result in heavy penalties from the state, and over-collecting can result in a class action lawsuit from customers.

Brick-and-mortar stores have long blamed everyone else for their decline: big department stores in the city, suburban shopping malls, catalogs, the Internet, and now the tax system. There is some truth in all of that, but brick-and-mortars also have the advantages of better locations for immediate purchases and deeper customer interaction. Changing the tax laws to impose new burdens on their competitors is not a productive solution for a state’s economic growth.

The real concern should be the extent of state powers. Should states be able to reach beyond their geographic borders and impose their tax system on everything everywhere? Do we really need to make sure that taxes are the same between New York and other states, and that people can’t shop by tax rates as they shop by price, quality, or convenience?

Unless every state has an identical tax system, there will be inconsistencies in taxes paid on items in different jurisdictions. Some states have high taxes and extensive public services while others prefer lower taxes and less extensive public services. This should not be viewed as a problem to be eradicated but rather an essential element of our federalism that should be embraced. Amazon taxes are incompatible with this notion of limiting states’ powers to prevent harm to the national economy, because they presume that states should have whatever power is needed to equalize tax rates.

Unconstitutionally Expansive Nexus Standards Like the Amazon Tax Undermine Legal Certainty, Interstate Commerce, and Economic Growth

The people of the United States adopted the U.S. Constitution in large part because their existing national government had no power to stop states from imposing trade barriers between each other, to the detriment of the national economy.24 In the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, Congress and the courts thus have the power to strike down laws that burden interstate commerce.

The economic and technological developments of the past few decades make preserving a bright-line physical presence nexus rule for state taxation all the more vital. The importance of the Commerce Clause and its protections for interstate business is only enhanced in an age of economic integration. “Today’s more integrated national economy presents far greater opportunities than existed in 1787 for states in effect to reach across their borders and tax nonconsenting nonbeneficiaries.” Daniel Shaviro, An Economic and Political Look at Federalism in Taxation, 90 Mich. L. Rev. 895, 902 (1992). Regrettably, because economic integration is greater now than it was in 1787, the economic costs of nexus uncertainty are also greater today and can ripple through the economy much more quickly.

Widespread adoption of vague and expansive nexus standards will expand these compliance costs and cause adverse impacts on interstate commerce. Compliance costs for businesses engaged in interstate commerce will increase. Businesses that merely expand their sales into such states will have to understand the local tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , any applicable tax rates, available tax incentives, and differing apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’s profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income tax or other business tax. US states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders. formulas. Differing nexus standards among the states means businesses will have to guess about whether to file and pay taxes or not.

Concerns about the cost of complying with multiple state tax systems, and the resulting economic harm, was at the heart of the Quill decision. The Court specifically recognized that economic harm that would come from requiring Quill to potentially collect tax in over 6,000 (now 8,000) separate tax jurisdictions, all with different tax systems.25 Such concerns are equally pressing in this case, where an unconstitutional and breathtakingly expansive nexus standard will lead either to a decrease in economic expansion or a lower rate of return for those that choose to press ahead.

Conclusion

The Amazon tax is just the latest in a series of efforts to eliminate the long-standing “physical presence” standard and replace it with a nebulous, arbitrary standard of “economic presence.” Businesses throughout our nation’s history could always ply their trade across state lines. Today, with new technologies, even the smallest businesses can more easily reach across geographical borders to sell their products and services in all fifty states. If such sales can now expose these businesses to tax compliance and liability risks in states where they merely have customers, they will be less likely to expand their reach into those states.

FOOTNOTES

1 Also known as affiliate nexus taxes or affiliate taxes.

2 See Henneford v. Silas Mason Co., 300 U.S. 577 (1937).

3 See Complete Auto Transit, Inc. v. Brady, 430 U.S. 274 (1977); National Bellas Hess, Inc. v. Dep’t of Revenue of State of Ill., 386 U.S. 753 (1967); Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298 (1992).

4 For an extended discussion, see my paper “Why the Quill Physical Presence Rule Shouldn’t Go the Way of Personal Jurisdiction”, 46 State Tax Notes 387 (2007), http://tinyurl.com/quillnexus.

5 Id.

6 Current members are Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin and Wyoming.

7 See, e.g., Joseph Henchman, “SSTP is Not All It’s Cracked Up to Be,” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog (Jul. 23, 2009), http://www.taxfoundation.org/legacy/show/24919.html; Mark Robyn, “I’ll Have Some Margarita Mix To Drink and a Packet of Lemonade Mix for Dessert,” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog (Jul. 7, 2009, http://www.taxfoundation.org/legacy/show/24827.html; Joseph Henchman, “Nearly 8,000 Sales Taxes and 2 Fur Taxes: Reasons Why the Streamlined Sales Tax Project Shouldn’t Be Quick to Declare Victory,” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog (Jul. 28, 2008), http://www.taxfoundation.org/legacy/show/23423.html.

8 See, e.g., John Buhl, “‘Amazon’ Laws Not Ideal Solution to Remote Sales Tax Issue, Panelists Say,” State Tax Today (Feb. 9, 2010), http://services.taxanalysts.com/taxbase/tbnews.nsf/Go?OpenAgent&2010+STT+26-1 (subscription req’d).

9 Joseph Henchman, “Colorado Modifies ‘Amazon Tax’ Proposal,” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog (Feb. 11, 2010), http://www.taxfoundation.org/legacy/show/25838.html.

10 See, e.g., Joseph Henchman, “Eight States Consider Adopting New York’s Problematic ‘Amazon Nexus’ Law,” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog (Apr. 22, 2009), http://www.taxfoundation.org/legacy/show/24638.html.

11 Cy Ryan, “Gibbons budget plan calls for higher taxes, fees,” Las Vegas Sun (Feb. 17, 2010), http://www.lasvegassun.com/news/2010/feb/17/gibbons-budget-plan-calls-higher-taxes-fees/.

12 R.I. H.B. 7071.

13 Ted Nesi, “‘Amazon tax’ has not generated revenue,” Providence Business News (Dec. 21, 2009), http://www.pbn.com/detail.html?sub_id=2976531d0961&page=1.

14 Shawn Collins, “Advertising Tax Generates Zero Taxes in Rhode Island,” AffiliateTip.com (Feb. 2, 2010), http://affiliatetip.com/news/article003119.php.

15 David Sims, “Virginia Advances Online Sales Tax Despite Track Record,” TMCNet (Feb. 11, 2010), http://voice-quality.tmcnet.com/topics/phone-service/articles/75297-virginia-advances-online-sales-tax-despite-track-record.htm.

16 Telephone interview with Robert Whitt, Spokesman, North Carolina Department of Revenue (Mar. 3, 2010).

17 Virginia Department of Taxation, Fiscal Impact Statement for S.B. 660, http://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?101+oth+SB660F161+PDF.

18 Michael Mazerov, “New York’s ‘Amazon Law’: An Important Tool for Collecting Taxes Owed on Internet Purchases,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities Report (Jul. 23, 2009).

19 Mazerov’s response was to a question posed by the author at a Tax Analysts panel on Feb. 5, 2010.

20 The Tax Foundation has filed an amicus curiae brief in support of Amazon.com in the appeal. See Joseph Henchman & Justin Burrows, “‘Amazon Tax’ Unconstitutional and Unwise,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact, No. 187 (Sep. 15, 2009), http://www.taxfoundation.org/legacy/show/25120.html (citing Tax Foundation Amicus Curiae Brief in Amazon.com, LLC v. New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, No. 601247-2008).

21 See Tyler Pipe Indus. v. Washington Dep’t of Revenue, 482 U.S. 232, 250 (1987) (stating that the non-employee’s activity must be “significantly associated with the taxpayer’s ability to establish and maintain a market in [the] state for [its] sales.”); Quill Corp., 504 U.S. at 249. See, e.g., Scripto, 362 U.S. at 211 (finding physical presence where 10 independent contractors engaged in a “local function of solicitation” that was “effective[] in securing a substantial flow of goods into [the state]”); Tyler Pipe, 482 U.S. at 251 (finding physical presence where in-state independent contractors “acted daily on behalf of [an out-of-state company] in calling on [in-state] customers and soliciting orders,” rendering them “necessary for maintenance of [the company’s] market and protection of its interests.”); Quill Corp., 504 U.S. at 249.

22 See Amazon.com LLC v. New York State Dept. of Taxation and Finance, 877 N.Y.S.2d 842, 849 (N.Y. Sup. 2009) (“Amazon further states that Associates’ referrals to New York customers are not significantly associated with its ability to establish and maintain a market for sales in New York… None of these allegations, however, sufficiently state a claim for violation of the Commerce Clause.”).

23 See Id. (“Amazon has not contested that it contracts with thousands of New Yorkers and that as a result of New York referrals to New York residents it obtains the benefit of more than $10,000 annually. Amazon should not be permitted to escape tax collection indirectly, through use of an incentivized New York sales force to generate revenue, when it would not be able to achieve tax avoidance directly through use of New York employees engaged in the very same activities.”).

24 See Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1, 224 (1824) (Johnson, J., concurring) (“[States’ power over commerce,] guided by inexperience and jealousy, began to show itself in iniquitous laws and impolitic measures . . ., destructive to the harmony of the states, and fatal to their commercial interests abroad. This was the immediate cause, that led to the forming of a convention.”).

25 See Quill, 504 U.S. at 313 n.6.

Share this article