One of the challenges policymakers face is designing solutions that are targeted at actual problems. If data concerning a problem is either low-quality or out-of-date, then developing solutions becomes rather difficult.

This challenge is particularly relevant to international tax policy. A problem that was identified in many studies at the beginning of the 21st century was that of companies using low-taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. jurisdictions as ways to avoid high taxes in their home countries. The U.S. system encouraged this type of behavior with its high corporate tax rate and rules for taxing foreign earnings if they were brought back to the U.S.

Since 2015, dozens of countries have changed their rules. However, the ink on these significant pieces of legislation had barely dried before countries began talking additional international tax changes, in some cases before the immense legislative changes had been fully implemented. It is critical for policymakers to understand what the data say about what has changed in the wake of policy reforms before considering more moves.

New research published this week by the Irish Ministry of Finance and authored by economist Seamus Coffey of University College Cork provides one such piece of data.

Prior to 2020, Ireland had rules that provided companies with an opportunity to game both Irish rules and U.S. rules to minimize exposure to taxes.

As researchers from the International Monetary Fund explain:

The so-called “Double Irish” structure offers a simple example of how [tax] residency laws can be manipulated. Under this formerly available structure, one Irish subsidiary (IRL1) would be an Irish-registered company selling products to non-U.S. locations from Ireland. A second Irish subsidiary (IRL2) would hold intangible assets and charge the IRL1 royalties, thereby shifting most profits to IRL2. IRL2 would be registered in Ireland but managed and controlled from a low-or no-tax jurisdiction. The Irish tax code considered IRL2 to be a resident of the low-tax jurisdiction (based upon the Irish “managed and controlled” test), but the US tax code considered IRL2 to be an Irish company (based on the place of incorporation or registration test). Neither jurisdiction therefore taxed the income of IRL2, as neither viewed it as legally resident within its jurisdiction.

They continue:

In 2015 Ireland closed this avenue of tax minimization by changing the definition of tax residence to include not only entities that are effectively managed in Ireland but also those incorporated there. However, [business] structures already in place were grandfathered until 2020.

The rules changed, so how have the data changed?

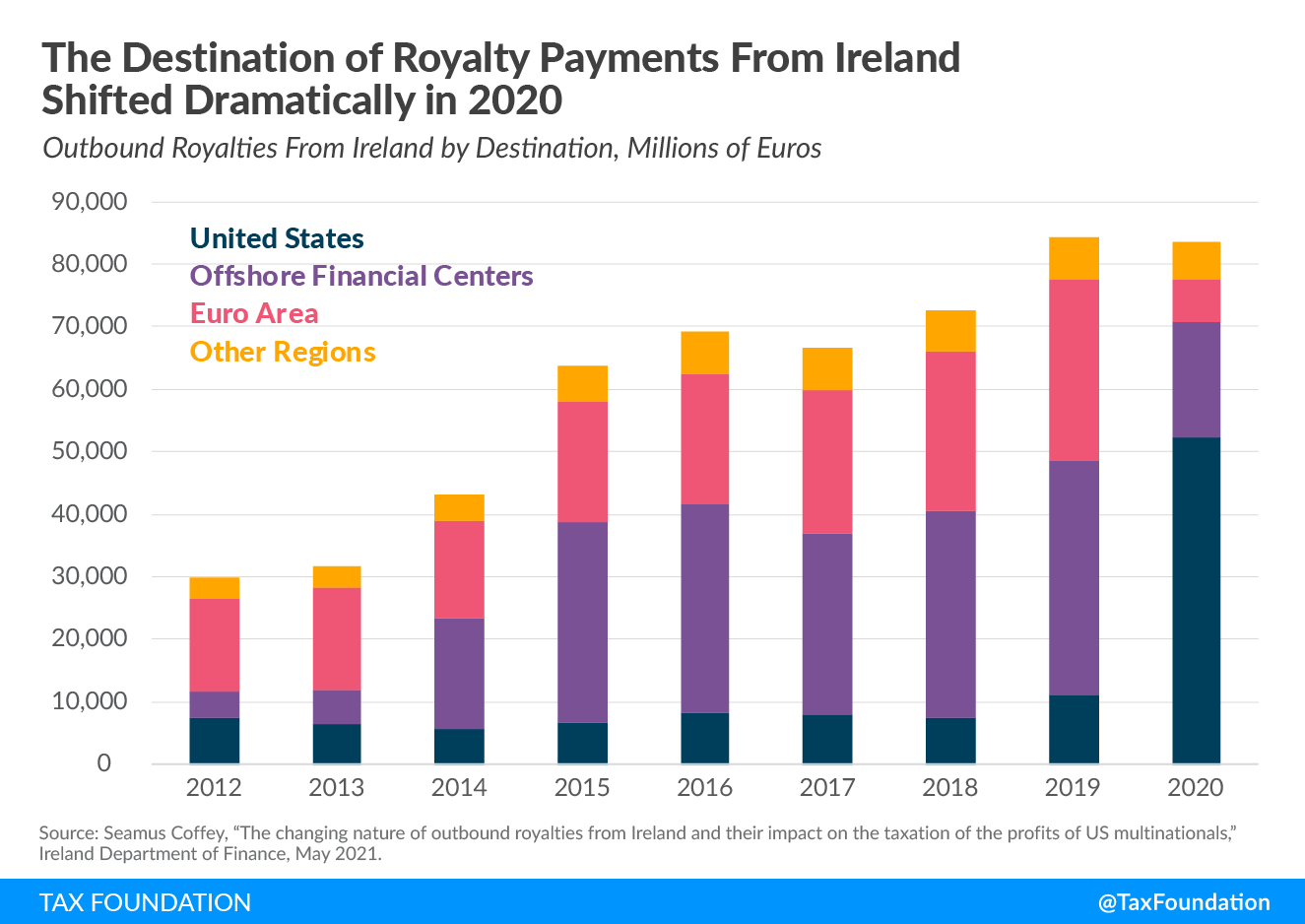

Coffey’s new paper shows how patterns in royalty payments (fees for use of intellectual property) shifted dramatically starting in 2020.

In 2019, nearly half of royalty payments from Ireland went to so-called “offshore financial centers” which might include the Cayman Islands, Bermuda, or another jurisdiction with an extremely low (or zero) corporate tax rate.

If a U.S. company developed software and put that software in a subsidiary in the Cayman Islands and then licensed that software to another subsidiary in Ireland, the royalty payments would be made to the entity in the Cayman Islands.

However, following the change in policy in 2020, most royalty payments from Ireland (62 percent) went directly to the United States.

Another piece to this story is the new U.S. rules that change the taxation of earnings from intangible assets known as Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) and Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII).

Paired together, these policies create an incentive for U.S. companies to no longer hold their intellectual property in foreign low-tax jurisdictions, but rather put that intellectual property in the United States.

When the intellectual property is in the United States, then royalty payments from the Irish subsidiaries of U.S. companies flow back to the U.S. rather than to another low-tax jurisdiction offshore.

These data (in addition to a recent survey of other evidence by my colleague) show that the recent policy changes that have been implemented by the U.S., Ireland, and dozens of other countries are having an impact. The question for policymakers is whether they will take the time to understand these impacts before jumping to the next project to change international tax rules yet again.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe