Greenhouse gas emissions—foremost carbon dioxide (CO2) but also methane, nitrous oxide, and F-gases—have been driving changes in global temperatures, imposing costs on economic, human, and natural systems. A carbon tax is a form of carbon pricing and, as a market-based approach, it is generally seen as a cost-effective way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The tax is levied on the carbon content of fossil fuels. The term can also refer to taxing other types of greenhouse gas emissions, such as methane. A carbon tax puts a price on those emissions to encourage consumers, businesses, and governments to produce less of them.

Amidst bipartisan climate negotiations on Capitol Hill, there have been renewed calls for a carbon tax. Carbon taxes have long been magnets for political controversy. But from an economic standpoint, they deserve to be taken seriously. And as with anything in tax policy, the details and design matter greatly. Federal policy analyst Alex Muresianu recently joined Jesse Solis on The Deduction podcast to talk through the history of climate tax policy, how a pro-growth carbon tax could be designed, and what its chances in DC actually are as the climate crisis worsens.

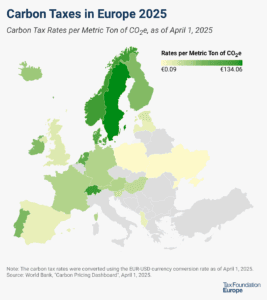

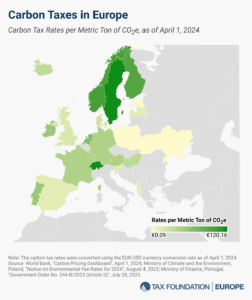

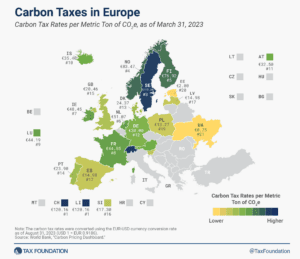

The economic theory behind such taxes is simple, but transforming the theory into a real-world policy is more challenging. You can learn more about carbon tax basics, the distributional and economic implications of a the tax, and relevant carbon policies and proposals across the globe, including those in Finland and Sweden, which were the first carbon taxes enacted in the world.

Learn more with TaxEDU