Bracket creep occurs when inflation, or real income growth, pushes taxpayers into higher income tax brackets. Bracket creep results in an increase in income taxes without an increase in real income. Many tax provisions—both at the federal and state levels—are adjusted for inflation. Over time, bracket creep can increase how much income tax people owe as their income grows, either due to inflation or economic growth. To prevent inflation-driven bracket creep, many tax provisions at the federal and state levels are adjusted for inflation.

An Example of Bracket Creep

If the tax code does not adjust where different tax brackets kick in each year, much like the federal tax code before inflation indexing began in 1985, more of your income will spill into higher tax brackets as inflation increases.

For example, imagine a simple tax system with two rates, 10 percent on your first $50,000 and 20 percent above $50,000. If your income is $50,000 this year, you pay 10 percent on all of it. But after your cost-of-living adjustment to account for inflation, your annual salary rises to $51,500—part of your income now faces the 20 percent bracket. You aren’t richer; a cost-of-living adjustment simply helps ensure you can purchase the same amount of goods and services over time, but without also making the same inflation adjustments to the tax system, taxes will take a larger bite out of your income over time.

Inflation Indexing Prevents Bracket Creep

Real bracket creep may also occur when incomes rise because of real wage growth, pushing taxpayers into higher tax brackets. A gain in real earnings, not just inflation, can mean taxpayers pay higher average tax rates over time as more of their income faces higher marginal tax rates. The tax code does not automatically adjust for real wage growth each year.

To prevent bracket creep from inflation, the tax code adjusts many tax provisions for inflation on an annual basis. At the federal level, the IRS adjusts more than 40 tax provisions for inflation, including the income thresholds on tax brackets to prevent bracket creep as well as dollar amounts for different deductions, exemptions, and credits, such as the standard deduction and the earned income tax credit (EITC), so that they do not lose value over time.

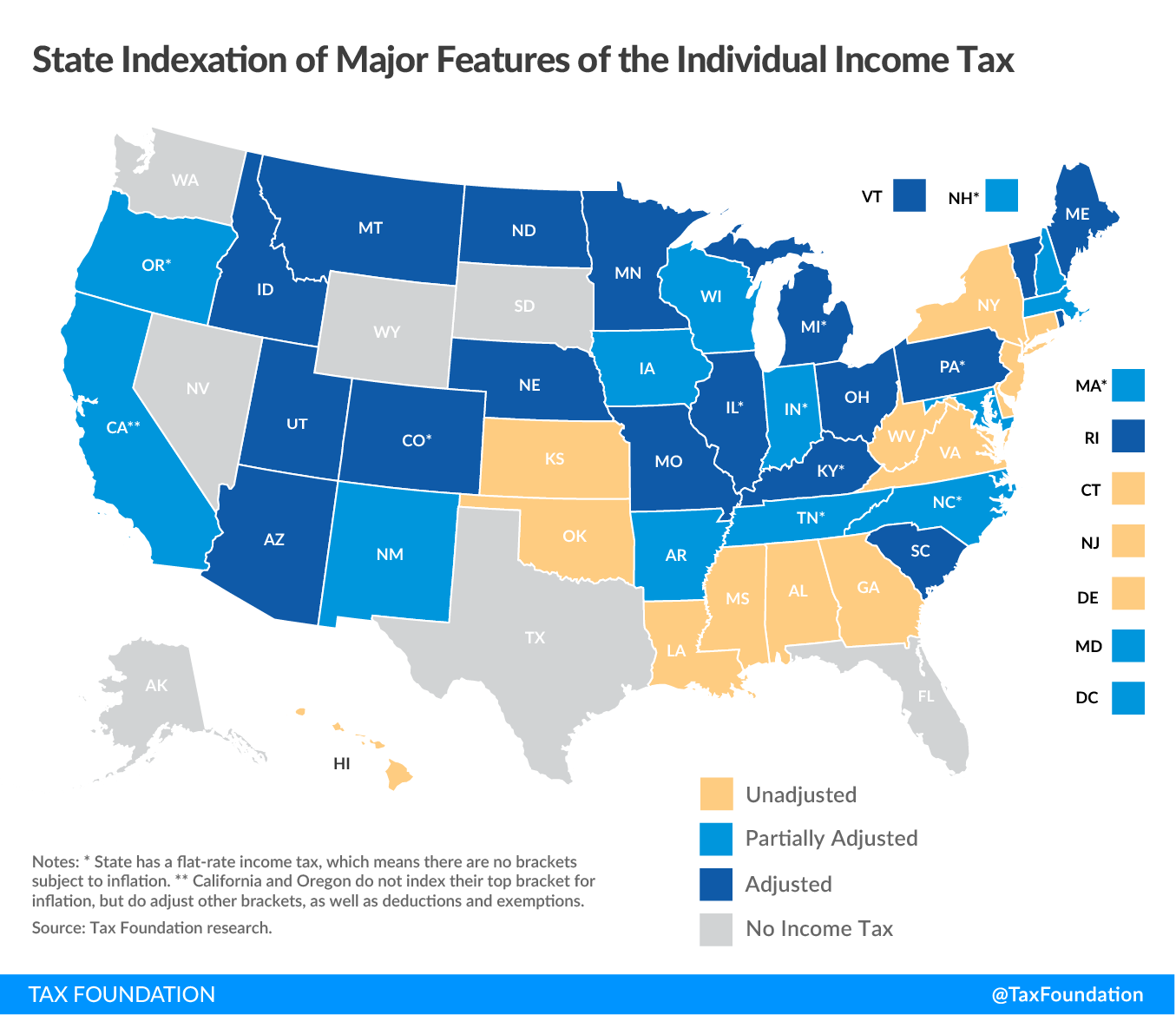

Many states build a cost-of-living adjustment into their individual income tax brackets, standard deductions, personal exemptions, and other features of their tax codes. A movement that began with three states—Arizona, California, and Colorado—in 1978 has now expanded to 24 states and the District of Columbia.

Inflation indexing also occurs at the international level. However, the practice varies across countries. For instance, fewer than half of European OECD countries adjust their personal income tax brackets annually for inflation. That means a substantial number of Europeans’ real earnings do not keep pace with the taxes they pay.

Stay updated on the latest educational resources.

Level-up your tax knowledge with free educational resources—primers, glossary terms, videos, and more—delivered monthly.

Subscribe