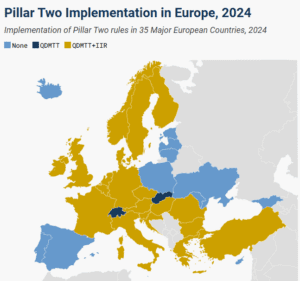

The Latest on the Global Tax Agreement

The agreement represents a major change for tax competition, and many countries will be rethinking their tax policies for multinationals. If there is no agreement on changes to Pillar Two or digital services taxes, retaliatory American tariffs could be on the horizon.

8 min read