Key Findings

- The Highway Trust Fund is facing an estimated $168 billion shortfall over the next decade and absent any general fund transfers will run out of funds by mid-year 2015, due to increased spending and an eroding gas taxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline. .

- Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have put forth permanent solutions, but political differences will likely mean lawmakers will opt to pass poor temporary policy such as pension smoothing and deemed or voluntary repatriationRepatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the US tax code created major disincentives for US companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. in order to keep the trust fund from going broke.

- If lawmakers decide to look for revenue for the trust fund, their source of revenue should be long-term and conform to the benefit principle.

- One option is to increase the gas taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. by about $168 billion over the next decade while cutting another tax by the same amount.

- This paper models the impact of raising the gas tax and offsetting it with one of five different tax cuts on GDP and the distribution of taxes paid.

Introduction

The federal government provides highway funding to states through an account called the Highway Trust Fund. This trust fund raises revenue mainly through taxes on gasoline. However, the trust fund currently does not raise sufficient revenue to cover its obligations. Absent recent congressional authorization for transfers from the general fund, the Highway Trust Fund would have run out of money in the summer of 2014.

The trust fund requires a solution that will permanently align expenditures with revenue, but Congress is divided on a solution. As a result, some members of Congress and the President are pursuing unsound tax policy as a temporary fix.

Lawmakers looking for additional revenue to replenish the trust fund should devise permanent provisions that conform to the trust fund’s long-standing, user-pays principle. One option to fix the trust fund is to raise the gas tax while offsetting that tax increase with an equal reduction in another tax. This paper illustrates the effects of several possible options. It uses the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth (TAG) macroeconomic model to estimate the effect of potential tax swaps on GDP and taxes paid per income quintile.

The Highway Trust Fund and Its Current Shortfall

The United States federal government funds highway and transportation spending through the Highway Trust Fund. The trust fund receives revenue from a series of excise taxes on gasoline and certain vehicles, then distributes that revenue to state and local governments in the form of grants to pay for transportation projects. Any unspent revenue is saved in the trust fund’s reserves. Under current law, the Highway Trust Fund cannot borrow money and must depend on its reserves when expenditures exceed revenue. When the reserves are exhausted, funds are distributed on a rolling basis as new revenue is received.

Taxes and spending associated with the Highway Trust Fund are based on the benefit principle of taxation. This principle states that the taxes one pays to the government should be connected to the benefits one receives. This principle is seen as an equitable way to finance government projects—in this case, roads and infrastructure. Those who drive on roads and cause wear are the ones who should pay for future repairs. This type of taxation also sets a price for driving on the road in order to prevent overconsumption in the form of congestion.

Since 2008, the Highway Trust Fund has spent more money than it has received, further depleting its reserves each year. From 2008 to 2014, without Congress’s authorization of $60 billion in transfers from the general fund,[1] the Highway Trust Fund would have run out of money. This year, the trust fund will run a deficit of about $15 billion and, absent another intervention from Congress, will run out of funds by mid-year 2015.

Over the long term, the Highway Trust Fund’s revenue will continue to fall short of spending. The CBO projects that from 2015 to 2025 the Highway Trust Fund will have a cumulative deficit of about $168 billion after adjusting for transfers (Chart 1).[2]

The Erosion of the Gas Tax

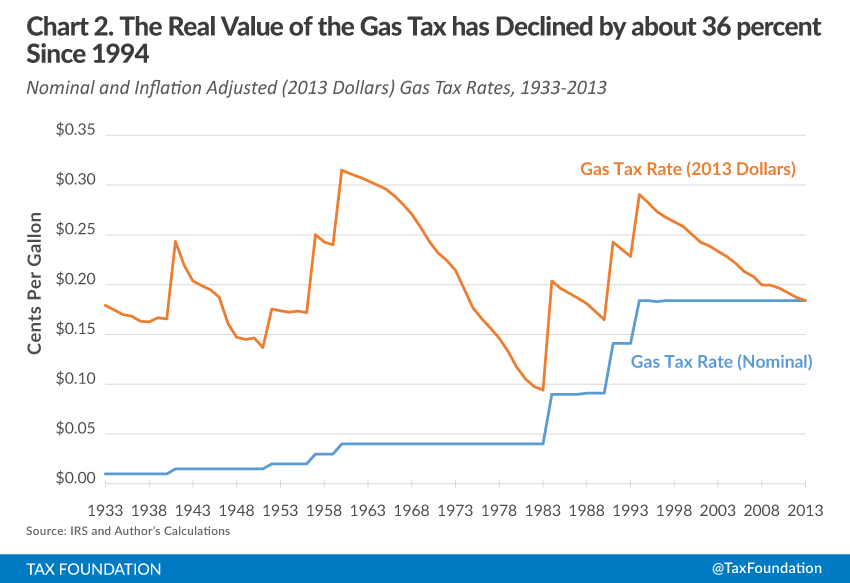

One of the main reasons why the Highway Trust Fund has insufficient revenue to cover its current obligations is the constant erosion of the value of the gas tax, its largest source of funding.[3] Unlike other taxes which are levied as a percentage of the value of a good (such as income and sales taxes), the gas tax is applied at a fixed value of $0.184 per gallon. When prices rise due to inflation, taxes like the sales tax capture that change and provide a nominal increase in revenue to match the increase in prices across the economy. The gas tax, however, does not respond to price changes. Over time, a nominal gas tax rate will decline in real terms, while the costs associated with funding roads will increase with inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. .

The federal gas tax was last increased in 1994 from the nominal rate of $0.141 per gallon to the current nominal rate of $0.184 per gallon.[4] When adjusted for inflation, the 1994 rate of $0.184 per gallon equals about $0.29 per gallon today. By 2013, inflation had reduced the real value of the gas tax by 36 percent.

Working in tandem with the decline in the real value of the gas tax, the improved fuel efficiency of cars has decreased trust fund revenue. Consumers now purchase less fuel to drive more miles, which increases the wear on roads while decreasing tax receipts. According to the United States Department of Transportation, the average fuel efficiency of a light duty vehicle has increased from 16 miles per gallon of gasoline in 1980 to 23.3 miles per gallon in 2012.[5]

A Permanent Fix Is Necessary But Politically Difficult

A permanent fix is necessary to ensure the Highway Trust Fund remains solvent. This will require a reduction in spending to meet revenue, an increase taxes to match spending, or a combination of both. Lawmakers have proposed various fixes, but there is a large political divide over how to address the trust fund.

There have been two recent proposals that highlight this divide. The first is from Senator Mike Lee (R-UT) and Congressman Tom Graves (R-GA). The lawmakers proposed The Transportation Empowerment Act, which would drop the gas tax to $0.037 per gallon and transfer nearly all highway funding responsibility to the states.[6] The second proposal, from Representative Earl Blumenauer (D-OR), would increase the gas tax to about $0.334 per gallon over a few years, then adjust the tax for inflation going forward.[7] Rep. Blumenauer would then look to ultimately eliminate the gas tax and replace it with a vehicle miles traveled (VMT) tax.

Although these two proposals would permanently address the trust fund’s solvency issues, it is highly unlikely that either will pass through Congress before the trust fund runs out of money this year.

Temporary Policy Does Not Fix the Trust Fund

As a result of the political divide over how to fix the trust fund, Congress has yet to develop a permanent solution. Instead, Congress has used deficit financing and budget gimmicks to transfer revenue from the general fund to the trust fund, in order to keep the fund solvent during the last several years. Most recently, Congress employed a gimmick called “pension smoothing,” which shifted forward future corporate tax revenue and transferred it to the trust fund. In effect, this provision did not raise any revenue; it merely created the appearance of a revenue-positive tax change under budget scoring rules, then transferred money from the general fund to the Highway Trust Fund in the amount of the illusory revenue score.[8]

Currently, there are two plans to fund the Highway Trust Fund through a one-time tax on U.S. multinationals’ offshore earnings. The first plan, from Senators Rand Paul (R-KY) and Barbara Boxer (D-CA), would allow U.S. multinational corporations to pay a discounted domestic tax rate on overseas income that they bring back to the states. Similar to pension smoothing, this “repatriation holiday” does not actually raise revenue in the long term. According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, the proposal only raises revenue in the first few years and loses money in subsequent years.[9]

The second plan is a provision in President Barack Obama’s fiscal year 2016 budget. This provision would deem all offshore corporate earnings repatriated and tax them at a flat 14 percent rate. In addition, the president’s budget would expand trust fund spending by $400 billion. The proposal to tax foreign earnings would raise only $280 billion, covering a little more than half of the new infrastructure spending. Due to the fact that this would be a one-time tax, it does not address the trust fund’s long-term solvency.

Past transfers from the general fund and proposed taxes on multinational corporations are both bad policies to fund the highway trust fund. Not only are they fiscally unsound, they violate the benefit principle, on which the trust fund is based. These transfers, in effect, will require more people who may not use roads to pay for benefits that drivers receive. This subsidizes road use for drivers and can lead to overuse or congestion.[10]

The two proposals to tax multinational corporations’ offshore earnings suffer from additional flaws. The repatriation holiday, although it appears to be a tax cut, would actually have no real economic benefits. Instead, it provides a retroactive subsidy for multinational corporations for past behavior. Conversely, the deemed repatriation tax from President Obama’s budget is retroactive and unfairly taxes companies on past behavior. Since it is levied on all overseas assets (reinvested or cash), the tax could put a financial strain on multinational corporations with substantial overseas investments.

Options to Reform the Highway Trust Fund’s Revenue

If Congress does pursue revenue options to fix the trust fund, they should avoid unsound tax policy. Instead, they should pursue permanent policy that conforms to the benefit principle. One option is to increase the gas tax, adjust it to inflation, and offset that increase by reducing another tax by the same amount of revenue.

This swap would be revenue neutral: an exchange of one tax for another. There are good policy reasons to raise more revenue from the gas tax in exchange for lowering the revenue received from other taxes.

- The gas tax is a relatively less distortive tax. The gas tax is an excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. , which falls mostly on consumption, assuming businesses can pass the tax onto consumers. Consumption taxes do not significantly impact the economy or reduce the incentive to invest. Comparatively, the capital gains income tax falls squarely on capital and thus has a significant negative effect on the economy. Lowering more distortive taxes and raising the same amount of revenue from non-distortive taxes would lead to a larger economy.

- The gas tax conforms to the benefit principle more closely than other taxes levied by the federal government. Although not perfect, the gas tax is better aligned with related government spending than, for example, the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. , which is not associated with any specific benefit. Lowering taxes that do not conform to the benefit principle of taxation and raising the gas tax is an opportunity to connect government revenue to related expenditures.

- Closing the funding gap in the Highway Trust Fund would grant lawmakers additional time to focus on other priorities. Rather than trying to search for the next temporary fix for the trust fund, lawmakers could focus on bigger questions: to what extent should the federal government be involved in infrastructure spending? How much should the federal government spend? What alternative funding mechanisms for the trust fund would best ensure its long-term solvency?

Modeling Revenue Neutral Fixes to the Trust Fund

Using the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth (TAG) Model, this section demonstrates the economic and distributional effects of increasing the gas tax and offsetting it with one of five selected tax cuts.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the Highway Trust Fund’s shortfall is $168 billion over ten years. To cover this shortfall, the gas tax would need to increase accordingly, to approximately $0.28 per gallon.[11] The gas tax would then be adjusted for inflation each year. In the first year, the gas tax will raise approximately $15 billion more than it currently does.

Five offsets that cut taxes by approximately $168 billion over the next ten years are:

- A 2 percentage point decrease in the capital gains taxA capital gains tax is levied on the profit made from selling an asset and is often in addition to corporate income taxes, frequently resulting in double taxation. These taxes create a bias against saving, leading to a lower level of national income by encouraging present consumption over investment. rate.

- A 2 percentage point decrease in the top marginal income tax rate.

- A $1,000 increase in the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot also itemize their deductions; it serves as an alternative. .

- A 1 percentage point decrease in the bottom marginal income tax rate.

- An expansion of the Earned Income Tax CreditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. .

Each of these tax cuts result in an approximately $15 billion tax cut in the first year.

Modeling the Increase in the Gas Tax

Increasing the gas tax by $168 billion over ten years results in a $16 billion (or 0.1 percent) smaller annual GDP in the long term (Chart 3 and Appendix Table 1, below). The gas tax increase would have a limited effect on the economy since the tax increase is small relative to the economy. Nearly all of the gas tax falls on consumption, which prevents altering incentives to save and invest. The gas tax increase would impact all income quintiles due to the slightly smaller GDP (Table 1, below). The after-tax income of the bottom quintile would fall the farthest in percentage terms (1.29 percent), because low-income individuals consume a greater amount of gas as a percentage of income.

Modeling the Gas Tax Increase with Selected Offsets

A 2 Percentage Point Decrease in the Capital Gains Tax Rate Exchanged for Gas Tax Increase

This option would cut the top marginal capital gains tax rate from 23.8 percent to 21.8 percent. A gas tax increase paired with this tax cut would boost GDP by about $99 billion over the long term (Chart 3). This is due to the fact that a cut in the capital gains tax rate reduces the cost of capital. The lower cost of capital gives individuals and businesses a greater incentive to save and invest, leading to a higher level of GDP.

The economic growth that would occur under a lower capital gains tax rate would positively impact individuals in all quintiles, resulting in higher pre-tax incomes (Table 1). However, this boost in pre-tax income would not be sufficient to offset the decreased purchasing power due to higher gas prices for the bottom quintile.

A 2 Percentage Point Decrease in the Top Marginal Income Tax Rate Exchanged for Gas Tax Increase

A 2 percentage point cut in the top marginal income tax rate (from 39.6 percent to 37.6 percent) in exchange for a gas tax increase would increase the GDP by $17 billion over the long run (Chart 3). This boost to GDP is much smaller compared to the growth effects of an equal cut in the capital gains tax rate because labor is far less sensitive to changes in taxes than in capital. Nonetheless, the lower tax rate will increase labor force participation, and in turn, increase economic growth.

A 2 percentage point cut in the top marginal income tax rate in exchange for a higher gas tax would lead to higher after-tax incomeAfter-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. only for the top quintile of income earners (Table 1). This is a result based on two factors: 1) the top rate applies to a small number of high-income individuals; 2) the growth effects of a cut to the top marginal income tax rate do not boost pre-tax income enough for the bottom four quintiles to offset the decreased purchasing power from the higher gas tax.

A $1,000 Larger Standard Deduction Exchanged for Gas Tax Increase

This option would increase the current standard deduction by $1,000. For single individuals the standard deduction would go from $6,300 to $7,300 and from $12,600 to $14,600 for married filers. Pairing a gas tax increase with an increase in the standard deduction would slightly decrease the size of the economy (by $5 billion) over the long run (Chart 3). The increased growth from the tax cut on labor would not be substantial enough to offset the negative impacts of the increased gas tax.

A $1,000 increase in the standard deduction in exchange for a higher gas tax would yield higher after-tax income for those with incomes that fall between the 2nd quintile and the 4th quintile, with the largest increase going to those in the middle quintile (Table 1). The higher standard deduction will reduce their taxable income which in turn will reduce their tax burden enough to offset the increase in the gas tax.

Those in the top quintile will have slightly lower after-tax incomes on average (-0.06 percent). While some of these higher income taxpayers may benefit from the high standard deduction, most won’t as they typically take itemized deductions. Those in the bottom quintile will also see lower after-tax incomes. Very few of these taxpayers have incomes high enough to have federal tax liability and will not benefit from a higher standard deduction.

A 1 Percentage Point Cut to the Bottom Marginal Tax Rate Exchanged for Gas Tax Increase

This would pair a gas tax increase with a rate reduction from 10 percent to 9 percent for the bottom income tax bracket. This swap would lead to a $12 billion smaller GDP in the long term (Chart 3). Although the tax cut increases the incentive to work, boosting output, it affects a relatively small number of people, earning a small share of the economy’s income, at the margin and thus fails to offset the effects of the gas tax increase.

This tax cut on income would lead to higher after-tax incomes for those in the middle and 4th income quintiles. For taxpayers in the 2nd quintile this tax cut would be just enough to offset the higher gas tax leaving no change in after-tax income.

Those in the bottom and top quintiles would see lower after-tax incomes because this tax rate cut affects very few of those taxpayers on the margin. These taxpayers’ incomes are either too low and thus don’t pay much or any income tax to begin with, or too high and would not get a large enough tax cut to completely offset the higher gas tax.

An Expansion to the EITC Exchanged for Gas Tax Increase

This final option would pair a gas tax increase with a $15 billion dollar expansion to the Earned Income Tax Credit.[12] This option would lead to a $29 billion smaller GDP (-0.2 percent) over the long term (Chart 3). The negative impact to GDP are caused by both the higher gas tax and the net effect of the EITC on the labor force. Although the EITC encourages many low-income individuals to participate in the labor force through its phase-in of benefits, it discourages more workers through its phase-out of benefits.

While this would reduce the level of GDP, it would be the most progressive of the five options. The bottom two quintiles would see higher after-tax income (0.70 percent for the bottom quintile and 1.30 percent for the second quintile). Since taxpayers in the top three income quintiles typically do not benefit from the EITC, they would see lower after-tax incomes due to the reduced purchasing power from the higher gas tax.

|

Table 1. Distributional Impact of Gas Tax Increase with Select Offsets Percent Change in After-Tax AGI |

||||||

|

Income Percentile: |

Bottom Quintile |

Second Quintile |

Middle Quintile |

Fourth Quintile |

Top Quintile |

|

|

A Gas Tax Increase Alone: |

-1.29% |

-0.63% |

-0.51% |

-0.38% |

-0.25% |

|

|

With: |

||||||

|

2 Percentage Point cut in Capital Gains Tax Rate |

-0.71% |

0.00% |

0.14% |

0.24% |

0.57% |

|

|

2 Percentage Point cut in Top Marginal Tax Rate |

-1.14% |

-0.47% |

-0.34% |

-0.22% |

0.19% |

|

|

$1000 Increase in Standard Deduction |

-1.17% |

0.23% |

0.27% |

0.11% |

-0.06% |

|

|

1 Percentage Point cut in Bottom Marginal Tax Rate |

-1.27% |

0.00% |

0.13% |

0.07% |

-0.06% |

|

|

Expansion of EITC |

0.70% |

1.03% |

-0.18% |

-0.24% |

-0.24% |

|

|

Source: Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Model Note: Gas tax modeled is approximately $168 billion over the next decade. Numbers represent the change in after-tax income from what it would have been in the absence of each tax change. For example, taxpayers in the top quintile have 0.25% lower after-tax incomes over the long run than they otherwise would have in the absence of the tax change. |

||||||

Conclusion

The Highway Trust Fund is set to run a deficit over the next ten years and needs a permanent fix. If no spending reforms are on the table, it’s important that any revenue increases adhere to the principles of sound tax policy. Unfortunately, the president and some in Congress have suggested a tax on foreign-earned profits of multinational corporations to provide stop gap funding for the trust fund and pay for additional infrastructure spending. This type of proposal violates a number principles of good government finance, among them, the user-pays principle which states that taxpayers should pay for the government services they use.

The Highway Trust Fund is a government program that largely adheres to the benefit principle by matching cost (gas tax) with benefits (improved roads). This structure should remain. However, a straight gas tax increase would be bad for growth and disproportionately tax the bottom two quintiles of income earners. To address these concerns, any increase in the gas tax would be best offset by a tax cut of an equal dollar amount.

We used the Taxes and Growth Model to estimate the costs and benefits of a revenue neutral gas tax package that would raise the gas tax by between $15 and $17 billion annually and offset this tax increase with a tax cut of an equal amount.

The model reveals a number of tradeoffs in this swap. If Congress would like to make this change pro-growth, one option would be to lower the capital gains tax rate. If Congress would like to address distributional concerns with the gas tax but aren’t concerned with economic growth, an option would be to expand the earned income tax credit. If Congress would like to maintain neutral distribution and growth while fixing the trust fund, one option would be to expand the standard deduction.

APPENDIX

| Appendix Table 1. Economic Effects of Gas Tax Increase with Selected Offsets | |||||

|

Change in GDP |

% Change in GDP |

% Change in Wage Rate |

Full-time Equivalent Jobs |

Dynamic Revenue Change |

|

|

A Gas Tax Increase of $15 Billion Alone: |

($16) |

-0.10% |

-0.20% |

-44,000 |

$8 |

|

With: |

|||||

|

2 Percentage Point cut in Capital Gains Tax Rate |

$99 |

0.60% |

0.40% |

73,000 |

$19 |

|

2 Percentage Point cut in Top Marginal Tax Rate |

$17 |

0.10% |

-0.10% |

56,000 |

$0 |

|

$1000 Increase in Standard Deduction |

($5.30) |

0% |

-0.15% |

8,800 |

($4) |

|

1 Percentage Point cut in Bottom Marginal Tax Rate |

($12) |

-0.10% |

-0.20% |

-24,000 |

($5) |

|

$15 Billion Expansion of EITC |

($29) |

-0.20% |

-0.20% |

-124,000 |

($10) |

|

Source: Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Mode. Dollars in Billions |

[1] Congressional Research Service, The Federal Excise Tax on Motor Fuels and the Highway Trust Fund: Current Law and Legislative History (Feb. 2015), http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL30304.pdf.

[2] Congressional Budget Office, Projections of Highway Trust Fund Accounts Under CBO’s January 2015 Baseline (Jan. 26, 2015), https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/43884-2015-01-HighwayTrustFund.pdf.

[3] About 90 percent of all Highway Trust Fund revenue comes from excise taxes on gas and diesel fuel. Congressional Budget Office, Alternative Approaches to Funding Highways (Mar. 23, 2011) https://www.cbo.gov/publication/22059.

[4] Internal Revenue Service, Historical Table 20, and Brian Francis, Gasoline Excise Tax, 1933-2000, Internal Revenue Service, http://www.irs.gov/file_source/pub/irs-soi/00gastax.pdf.

[5] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Table 4-23: Average Fuel Efficiency of U.S. Light Duty Vehicle, http://www.rita.dot.gov/bts/sites/rita.dot.gov.bts/files/publications/national_transportation_statistics/html/table_04_23.html.

[6] Office of Representative Tom Graves and Office of Senator Mike Lee, The Transportation Empowerment Act, http://tomgraves.house.gov/tea/.

[7] Office of Representative Earl Blumenauer, The Update, Promote, and Develop America’s Transportation Essentials (UPDATE) Act, http://blumenauer.house.gov/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2268:blumenauer-joined-by-leaders-in-transportation-commerce-labor-construction-to-introduce-update-act-to-fund-infrastructure&catid=66&Itemid=73.

[8] Alan Cole, The Highway Bill Pension Gimmick: A Primer, Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog (Jul. 15, 2014), https://taxfoundation.org/blog/highway-bill-pension-gimmick-primer.

[9] The repatriation holiday is estimated to cost $95 billion over ten years. Joint Committee on Taxation, Letter to Senator Hatch (Jun. 6, 2014), http://www.hatch.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/1b24c4cf-6005-4a4e-bab7-3d9e3820c509/JCT%206-6-14.pdf.

[10] Joseph Henchman, Gasoline Taxes and User Fees Pay for Only Half of State & Local Road Spending, Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 410 (Jan. 3, 2014), https://taxfoundation.org/article/gasoline-taxes-and-user-fees-pay-only-half-state-local-road-spending.

[11] According to the CBO, for every cent increase in the gas tax, the tax will raise $1.5 billion annually. Further, they estimate that the gas tax would need to increase by 10 to 15 cents per gallon to cover current obligations. We use the low-end estimate of 10 cents per gallon, or about $15 billion in the first year. Congressional Budget Office, The Highway Trust Fund and the Treatment of Surface Transportation Programs in the Federal Budget (Jun. 2014), http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/45416-TransportationScoring.pdf.

[12] The specific EITC expansion modelled was a nearly doubling of the benefit for childless individuals and couples. In addition, the income level at which the EITC phases out for these taxpayers was increased to match that of recipients with children.