Key Findings

-

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act created the Opportunity Zones program to spur investment in economically distressed census tracts. Opportunity zones reduce capital gains taxes for individuals and businesses who invest in qualified opportunity zones.

-

Opportunity zones were estimated to cost $1.6 billion in revenue from 2018-2027. New regulations stipulate that the program’s benefits would continue through 2047, meaning the program’s revenue impact could increase over time depending on how many investors utilize the program.

-

Research suggests place-based incentive programs redistribute rather than generate new economic activity, subsidize investments that would have occurred anyway, and displace low-income residents by increasing property values and encouraging higher skilled workers to relocate to the area.

-

While opportunity zones present certain budgetary and economic costs, it is unclear whether opportunity zone taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. preferences used to attract investment will actually benefit distressed communities.

Introduction

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) created the Opportunity Zones program to increase investment in economically distressed communities. The program provides preferential capital gains treatment for investments within designated low-income census tracts. Policymakers hope opportunity zones will unleash investment in low-income communities throughout the country.[1]

This analysis describes opportunity zone program incentives, reviews both academic and government evidence on the effects of place-based incentive programs, and discusses possible outcomes for opportunity zone residents. Overall, we find opportunity zones will present certain budgetary and economic costs to taxpayers and investors, but based on evidence from other place-based incentive programs, we cannot be certain opportunity zones will generate sustained economic development for distressed communities.

Capital Gains Taxes

A capital gain is the profit earned when an asset, such as an investment or property, is sold. Short-term capital gains, or profits on assets sold within one year of purchase, are taxed at a taxpayer’s ordinary income tax rate. Long-term capital gains, or gains from assets held longer than a year, are taxed at either 0 percent, 15 percent, or 20 percent, based on a taxpayer’s income.[2] Individuals with income above $200,000 ($250,000 for married filers) are subject to an additional 3.8 percent tax on their net investment income.[3]

Consider an investor who bought shares in a company for $25,000. Ten years later, the value of those shares has increased to $50,000. The investor then sells those shares, realizing a capital gain of $25,000 on the original investment. Assuming the investor’s income triggers a 15 percent tax on this capital gain, their tax liability would be $3,750. This brings the investor’s total post-tax earnings to $21,250.

| Traditional Investment | |

|---|---|

|

Source: Authors’ Calculation |

|

|

Original Investment: |

$25,000 |

|

Sold for: |

$50,000 |

|

Capital Gain: |

$25,000 |

|

Capital Gain Tax Rate: |

15% |

|

Capital Gain Tax Due: |

$3,750 |

|

Post-Tax Earnings: |

$21,250 |

Opportunity Zones

The Opportunity Zones Program attracts investment to economically distressed communities by modifying this standard tax treatment of capital gains in several ways. These modifications either delay or reduce the capital gains taxA capital gains tax is levied on the profit made from selling an asset and is often in addition to corporate income taxes, frequently resulting in double taxation. These taxes create a bias against saving, leading to a lower level of national income by encouraging present consumption over investment. liability of investors. But to qualify for these benefits, investors must reinvest one or more capital gains in a Qualified Opportunity Fund (QOF).[4]

Qualified Opportunity Funds

The TCJA describes a QOF as any investment vehicle organized as a partnership or corporation that holds 90 percent or more of its assets in qualified opportunity zone property, other than another qualified opportunity fund.[5] Proposed regulations would require 70 percent, or “substantially all,” of a business’s tangible business property be in an opportunity zone to qualify for QOF funding. Combining the 90 percent asset requirement for opportunity funds with the 70 percent tangible property requirement for qualifying businesses means that a QOF may be as minimally invested in a zone as 63 percent.[6] These proposed regulations would also require that “50 percent of the gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total of all income received from any source before taxes or deductions. It includes wages, salaries, tips, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental income, alimony, pensions, and other forms of income. For businesses, gross income (or gross profit) is the sum of total receipts or sales minus the cost of goods sold (COGS)—the direct costs of producing goods, including inventory and certain labor costs. of a qualified opportunity zone business [be] derived from the active conduct of a trade or business in the qualified opportunity zone.”[7]

Tax Treatment of QOF Investments

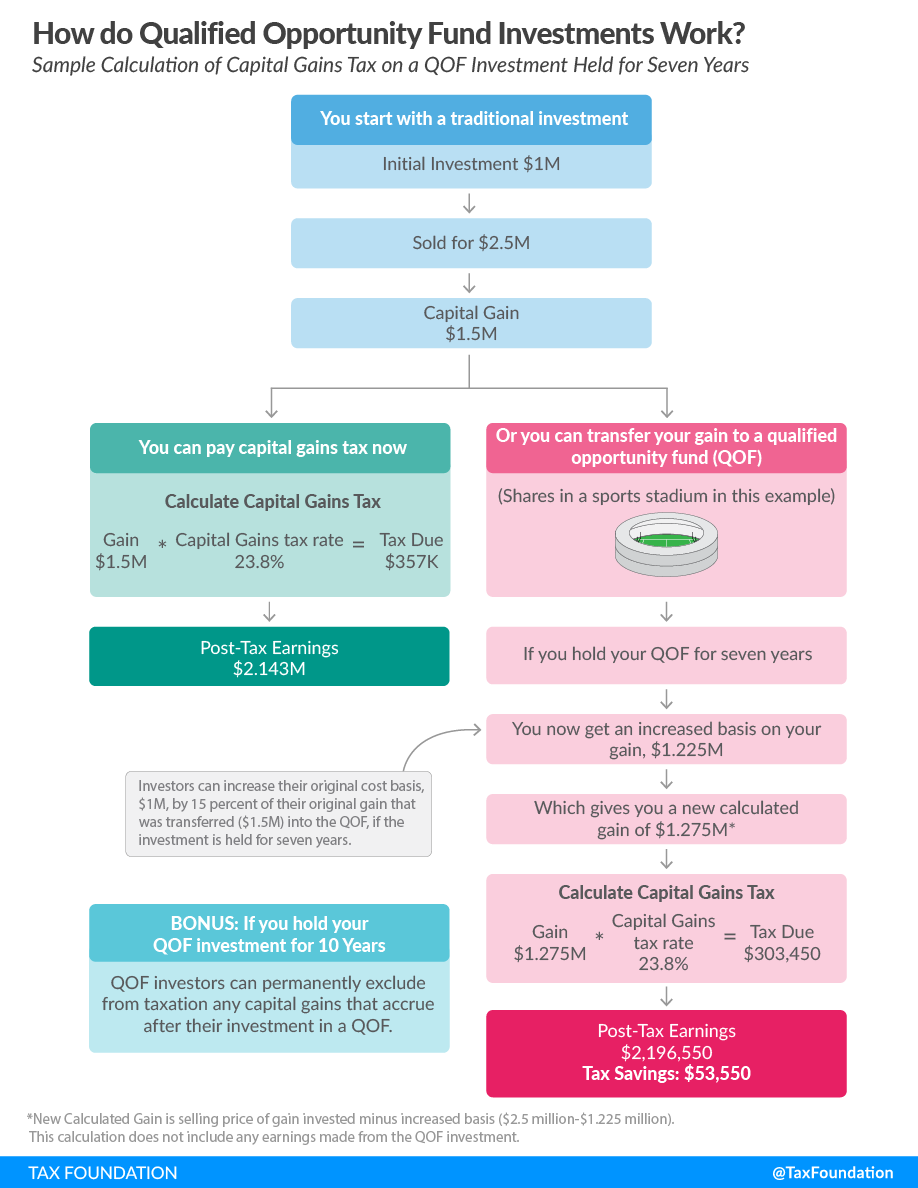

An investor can receive up to three tax benefits by reinvesting capital gains in a QOF.[8] The first is temporary tax deferral on any capital gains reinvested in a QOF within 180 days of realization.[9] Tax payment is deferred until the investment is sold or exchanged, or until December 31st, 2026, whichever comes first.[10]

The second benefit is a 10 percent step-up in basisThe step-up in basis provision adjusts the value, or “cost basis,” of an inherited asset (stocks, bonds, real estate, etc.) when it is passed on, after death. This eliminates the capital gains tax owed by the recipient, reducing the heir’s tax liability. The cost basis receives a “step-up” to its fair market value, or the price at which the good would be sold or purchased in a fair market. for capital gains reinvested in a QOF if the investment is held for five years. The basis is increased an additional 5 percent for any investments held for seven years.[11] This step-up in basis means taxpayers can exclude up to 15 percent of the value of their reinvested capital gains from their taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , decreasing the investor’s tax liability when they sell or can no longer defer taxation.[12]

Finally, QOF investors can permanently exclude from taxation any capital gains that accrue after their investment in a QOF, if the investment is held for at least 10 years. Opportunity zones increase the basis of any investment held in a QOF for 10 years to 100 percent of its fair market value on the date it is sold or exchanged.[13]

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeTable 2 provides an example of the tax savings opportunity zones can provide to an investor who holds an investment in a QOF for seven years. This sample investor had originally invested $1 million and sold it for $2.5 million, for a gain of $1.5 million. Under the traditional system, they would owe $357,000 in capital gains taxes. However, if the investor invested the $2.5 million in a QOF, they would save $53,550 in capital gains taxes. This is because the step-up in basis means they pay taxes on just $1.275 million in capital gains rather than the original capital gain of $1.5 million.

| Traditional Investment | QOF Investment Held for Seven Years | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Note: Investors can increase their original cost basis, $1M, by 15 percent of their original gain that was transferred ($1.5M) into the QOF, if the investment is held for seven years. This calculation does not include any earnings made from the QOF investment. |

|||

|

Original Investment: |

$1,000,000 |

Original Investment: |

$1,000,000 |

|

Sold for: |

$2,500,000 |

Sold for: |

$2,500,000 |

|

Capital Gain: |

$1,500,000 |

Capital Gain Transferred to QOF: |

$1,500,000 |

|

Capital Gain Tax Rate: |

23.80% |

Increased Basis: |

$1,225,000 |

|

Capital Gain Tax Due: |

$357,000 |

New Calculated Gain: |

$1,275,000 |

|

Post-Tax Earnings: |

$2,143,000 |

Capital Gain Tax Rate: |

23.80% |

|

Capital Gain Tax Due: |

$303,450 | ||

|

Post-Tax Earnings: |

$2,196,550 | ||

|

Tax Savings: |

$53,550 | ||

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeTable 3 shows that any gain accrued after the $1.5 million investment in the QOF is exempt from taxation if it is held for 10 years or longer. Assuming the investor made another $500,000 over the decade of the QOF investment, the investor would save an additional $119,000 in taxes.

| Traditional Investment | Earnings Accrued from QOF Investment Held Ten Years | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Source: Authors’ Calculations |

|||

|

Original Investment: |

$1.5 million |

Original Investment: |

$1.5 million |

|

Sold for: |

$2 million |

Sold For: |

$2 million |

|

Capital Gain: |

$500,000 |

Capital Gain: |

$500,000 |

|

Capital Gain Tax Rate: |

23.80% |

Capital Gain Tax Rate: |

0% |

|

Capital Gain Tax Due: |

$119,000 |

Capital Gain Tax Due: |

$0 |

|

Post-Tax Earnings: |

$381,000 |

Post-Tax Earnings: |

$500,000 |

|

Tax Savings: |

$0 |

Tax Savings: |

$119,000 |

In total, this sample investor saves $172,550 in taxes by reinvesting their $1.5 million capital gain in an opportunity zone and holding that investment for 10 years.

Budgetary and Economic Costs of the Opportunity Zone Program

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates the Opportunity Zones program will cost $1.6 billion between 2018 and 2027. The program is estimated to decrease revenue between 2018 and 2025 but generate revenue in 2026 and 2027, as investors can no longer defer taxes on the capital gains they reinvested in QOFs.[14]

|

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1, The ‘Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.’” |

||||||||||

|

Opportunity Zone Cost (Billions of Dollars) |

2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 |

| -1.2 | -1.7 | -1.6 | -1.7 | -1.6 | -1.5 | -1.5 | -1.6 | 8.1 | 2.7 | |

Importantly, new regulations stipulate that the program’s benefits would continue through at least 2048, meaning the revenue impact of the program could increase over time depending on how much activity occurs within opportunity zones.[15]

We also know that, as with any tax provision, the economic cost of the program will exceed its budgetary cost. Navigating the program’s new set of rules and regulations will generate direct compliance costs for investors, and investors will forgo investments in other areas of the economy to take advantage of the program’s tax incentives.[16]

Evidence on Place-Based Incentive Programs

Governments use place-based incentive programs to subsidize firms or investors who operate in specific areas, often with the intent to revitalize economically depressed communities. In the U.S., place-based incentive programs occur at all levels of government and are often (but not always) called “Enterprise Zones.”

These zones operate in areas with some mixture of high unemployment, population decline, vacant buildings, or residents with low income or low education levels. They usually require qualifying firms or investors to create a specified number of jobs or maintain a certain level of wages for residents within the zone. In return, firms and investors receive benefits like corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. credits for job creation and investment, sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. exemptions, or financial assistance through low interest rate loans. Some programs also provide benefits like workforce development within these areas.[17]

Several theoretical rationales underpin these programs. First, the cost of doing business in economically distressed areas is higher for several reasons, including less access to skilled labor and transportation, as well as higher crime. Theoretically, subsidies offered by place-based incentive programs can offset these costs and encourage businesses to locate in distressed areas.[18]

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeThe “spatial mismatch” theory argues people can become trapped in low-income areas for several reasons, such as an inability to incur the cost of moving to and living in a more productive area. In theory, place-based incentives can draw investment that will generate employment opportunities for immobile residents.[19]

Some have also argued place-based incentive programs can attract highly-skilled people to productive urban centers where they can experiment, innovate, and learn from other highly skilled people. These productive “agglomeration economies” then generate benefits that “spill over” to other areas of the economy.[20]

However, measuring the effectiveness of place-based incentive programs is challenging. For one, program boundaries are not always delineated by census tracts or zip codes, making data collection difficult.[21] And even when data is available, oftentimes, multiple place-based programs intervene in the same area, making it difficult to isolate the effects of one program relative to another. Making matters more complicated, it is difficult to find areas that are similar to zones but have not received benefits.[22] Without a counterfactual, it’s difficult to measure success.[23]

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given these measurement difficulties, there is no academic consensus on whether place-based incentive programs work as intended. In fact, research suggests programs fail to generate new employment often because subsidized firms replace nonsubsidized firms, or because firms simply shift their current business activities for tax purposes. Research also suggests the benefits of place-based incentives accrue primarily to landowners and higher-skilled mobile workers who can travel for employment, effectively displacing the low-income residents the programs are meant to help. [24]

Displacement Effects

Opportunity zone tax breaks will attract investment (at least in the short term) and this capital will require labor. But investors are not required to create jobs that fit the skills of zone residents.[25] If these investments generate employment opportunities that do not match the skills of existing residents, workers from outside the jurisdiction could take the employment opportunities instead.[26]

Evidence shows that this skills mismatch problem does occur. For instance, Maryland’s Department of Legislative Services (DLS) found “a significant mismatch between the skills of those who fill[ed] the private jobs within enterprise zones and those who reside[d] in or near the zones.”[27] Overall, DLS estimated only about one in eight enterprise zone jobs, or 12 percent, were filled by community residents. DLS concluded:

While enterprise zone tax credits may incentivize some businesses to create additional jobs within enterprise zones, the tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. is not effective in providing employment to zone residents that are chronically unemployed and/or live in poverty. A number of factors contribute to this problem, including skills mismatches for new jobs created, lower than average educational attainment levels of zone residents, and labor mobility.[28]

Place-based incentives can also pressure nonsubsidized firms out of business by providing subsidies to their competitors. For instance, in a 2010 report, Louisiana Economic Development cautioned that of the 9,379 jobs attributed to the state’s Enterprise Zone program in 2009, only 3,000 jobs could be considered new. The report cautioned many of the projects associated with the program would have occurred regardless of the incentive, and many new jobs simply replaced others.[29]

Place-based incentive programs could displace low-income residents by increasing property values.[30] As capital and labor move into a zone, this could put upward pressure on wages and housing prices. While this would benefit landowners in a region, it could be problematic to low-income individuals if it makes housing unaffordable. In the case of opportunity zones, the site-selection process which places zones in gentrifying areas could exacerbate this effect.[31]

Opportunity Zone Data is Necessary to Compare the Program’s Outcomes with Alternative Approaches

Given that there is no consensus on the efficacy of place-based incentive programs, gathering data on opportunity zones is crucial. Senators Corey Booker (D-NJ) and Tim Scott (R-SC) had originally included provisions for annual data collection beginning five years after the bill passed, but those provisions were dropped in the final version of the TCJA.[32]

Without data, it is impossible to judge the merits of place-based incentive programs relative to other economic development approaches. Take the federal government’s experience with Empowerment Zones, Enterprise Communities, and Renewal Communities, all place-based incentive programs that subsidized firms for locating in particular areas to help develop distressed communities. In 2010, the Government Accountability Office found:

[D]ata limitations make it difficult to accurately tie the use of the credits to specific designated communities. It is not clear how much businesses are using other EZ, EC, and RC tax incentives, because IRS forms do not associate these incentives with the programs or with specific designated communities.… making it difficult to begin assessing the impacts of these tax benefits.[33]

Fortunately, future rounds of opportunity zone regulations will likely include reporting requirements that would allow economists to evaluate program impacts.[34] The White House has also created an Opportunity and Revitalization Council that will, among other things, assess “what data, metrics, and methodologies can be used to measure the effectiveness of public and private investments in urban and economically distressed communities, including qualified opportunity zones.”[35] Both developments can help policymakers assess the effectiveness of opportunity zones relative to other economic development policies.[36]

Conclusion

With opportunity zones, and any other place-based incentive program, it’s important to consider what we know, as well as what we don’t. We know the program will attract at least some investment to low-income census tracts designated as zones. We also know that this investment will come at both a budgetary and economic cost.

But we don’t know how effective opportunity zones will be at improving the lives of low-income people in economically distressed communities. Both research and state level experience raise concerns that opportunity zones could actually be counterproductive to generating sustained development in these communities.

For now, policymakers should emphasize the data collection necessary to measure the effects of this program. Without it, we will be unable to measure the merits of this place-based approach compared to other alternatives that could more effectively develop economically distressed communities.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNotes

[1] In his May testimony before the Joint Economic Committee, Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC), an Opportunity Zone supporter, said: “We have trillions of dollars in unrealized capital gains in this country—trillions of dollars sitting dormant. By changing the way capital gains are treated, encouraging long-term investments in distressed communities in exchange for a break on capital gains taxes, we believe we will see hundreds of billions of private dollars invested in low-income communities.” See United States Joint Economic Committee, “The Promise of Opportunity Zones” – News Release – May 17, 2018, https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/hearings-calendar?ID=2A2DE9B9-0105-4612-9C41-D9EC9257B707.

[2] In 2019, capital gains for individual taxpayers will be taxed at 0 percent if an individual’s income is below $38,600, 15 percent if an individual’s income is between $38,600 and $425,800, and 20 percent if an individual’s income is above $425,800. See 26 USC § 1- (j)(5)(A-B).

[3] Internal Revenue Service, “Questions and Answers on the Net Investment Income Tax,” June 18, 2018, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/questions-and-answers-on-the-net-investment-income-tax.

[4] 26 USC § 1400Z-2 (a).

[5] Qualified opportunity zone property includes qualified stock, a qualified partnership interest, or qualified business property. The TCJA places several requirements on each type of property that makes them qualified opportunity zone property. For more information see 26 USC § 1400Z-2 (d)(1-2).

[6] Alec Fornwalt and John Buhl, “Treasury Department Proposes New Regulations for Opportunity Zones,” Tax Foundation, Oct 22, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/new-proposed-opportunity-zones-regulations/.

[7] Several businesses are automatically disqualified from being qualified opportunity zone businesses, including: “any private or commercial golf course, country club, massage parlor, hot tub facility, suntan facility, racetrack or other facility used for gambling, or any store the principal business of which is the sale of alcoholic beverages for consumption off premises.” See “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Creates Opportunity Zones in Low Income Communities,” BDO USA, February 2018, https://www.bdo.com/insights/tax/state-and-local-tax/tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-creates-opportunity-zones-in. For more on opportunity zone regulations, see “Investing in Qualified Opportunity Funds, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking and Notice of Public Hearing,” Internal Revenue Service,” Oct. 29, 2018, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/10/29/2018-23382/investing-in-qualified-opportunity-funds.

[8] 26 USC § 1400Z-2(b-c).

[9] See 26 USC § 1400Z-2(a)(1-A). Regulations proposed by the IRS and U.S. Treasury would add 30 months to this 180-day limit for certain businesses with “working capital.” These are businesses with investments that take longer to realize because they are dependent on construction (such as real estate development). Such businesses can take advantage of this extended deferral period so long as they have plans for a qualified project that may be audited by the IRS. See “Investing in Qualified Opportunity Funds, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking and Notice of Public Hearing.”

[10] See 26 USC § 1400Z-2(b-1).

[11] See 26 USC § 1400Z-2(b)(2-b).

[12] Investors must invest their capital gains in a QOF before the end of 2019 to receive the full 15 percent step-up in basis after seven years. This is because the TCJA requires investors to realize deferred gains by the end of 2026. See Roger Russell, “Tax experts weigh in on Qualified Opportunity Zones,” AccountingToday, Dec. 3, 2018, https://www.accountingtoday.com/news/tax-experts-weigh-in-on-qualified-opportunity-zones. Note also that the step-up in basis reduces the taxable amount of a reinvested capital gain even if the gain loses value between investment and realization, providing a tax benefit to investors who experience capital losses. See Forrest David Milder, “INSIGHT: A Dozen Things You Should Know About Setting Up an Opportunity Fund,” Bloomberg Tax, Nov. 29, 2018, https://news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report/insight-a-dozen-things-you-should-know-about-setting-up-an-opportunity-fund?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=taxdesk&utm_campaign=6pm.

[13]See 26 USC § 1400Z-2(c).

[14] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1, The ‘Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,’” JCX-67-17, Dec. 18, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053.

[15] “Investing in Qualified Opportunity Funds, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking and Notice of Public Hearing.”

[16]See, for instance, Kyle Pomerleau, “The Higher Education and Skills Obtainment Act: A Proposal to Reform Higher Education Tax Credits,” Tax Foundation, July 24, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/higher-education-and-skills-obtainment-act-proposal-reform-higher-education-tax-credits, and Erik Cederwall, “Tax Foundation Forum: Making Sense of Profit ShiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens. ,” Tax Foundation, May, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-foundation-forum-making-sense-profit-shifting.

[17] Good Jobs First, “Enterprise Zones,” https://www.goodjobsfirst.org/accountable-development/enterprise-zones. See also Helen F. Ladd, “Spatially Targeted Economic Development Strategies: Do They Work?” Cityscape, January 1994, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Helen_Ladd/publication/242273411_Spatially_Targeted_Economic_Development_Strategies_Do_They_Work/links/0c960533c2a593446d000000/Spatially-Targeted-Economic-Development-Strategies-Do-They-Work.pdf.

[18] See Department of Legislative Services, Office of Policy Analysis, Maryland General Assembly, “Appendix 3: Studies of Enterprise Zone Programs,” in “Evaluation of the Enterprise Zone Tax Credit,” November 2013, http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/pubs/budgetfiscal/2013-evaluation-enterprise-zone-tax-credit-draft.pdf.

[19] See “Section 2.4: Spatial Mismatch,” in David Neumark and Helen Simpson, “Place-based policies,” Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, August, 2014, http://sbsplatinum-prod.sbs.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Business_Taxation/Docs/Publications/Working_Papers/series-14/WP1410.pdf.

[20] See “Section 2.1: Agglomeration economies” and “Section 2.2: Knowledge spillovers and the knowledge economy,” in David Neumark and Helen Simpson, “Place-based policies.”

[21] Opportunity zones are easier in some ways. For instance, they are delineated by census tracts, and the fact that there could be some census tracts that were similar (but not chosen) could give researchers a counterfactual. But the fact that measurement difficulties have kept researchers from finding a consensus puts policymakers on unsure footing to know whether the program will be successful.

[22] Oregon’s Legislative Revenue Office (LRO) provides an example of how counterfactuals can be created to measure a program’s effectiveness. LRO identified comparison areas for each of its enterprise zone regions using employment data at the two-digit North American Industry Classification System private industry code level. While they could not identify perfect counterfactuals, their estimate was close to an apples-to-apples comparison. Careful methods should be adopted by more government program evaluators. See State of Oregon’s Legislative Revenue Office Research Report, “Enterprise Zones Study,” April 1, 2009, https://www.oregonlegislature.gov/lro/Documents/entr_prz_zones_sb151.pdf.

[23] For a complete discussion of data issues related to measuring the effects of place-based incentives, see “Section 4: Identifying Effects of Place-Based Policies,” in David Neumark and Helen Simpson, “Place-based policies.”

[24] In addition to Neumark and Simpson, see Department of Legislative Services, Office of Policy Analysis, Maryland General Assembly, “Appendix 3: Studies of Enterprise Zone Programs” of “Evaluation of the Enterprise Zone Tax Credit.”

[25] And based on proposed regulations, investors can have more than a third of their investments in property not within opportunity zones, but still receive the program’s preferential tax treatment.

[26] See “Section 2.6: Equity motivations for place-based policies,” in David Neumark and Helen Simpson, “Place-based policies.”

[27] Of Maryland’s five Enterprise Zone regions, only one region’s employment figures consisted of more than 10 percent low-skilled jobs (12 percent of jobs in “Capital Region” were low-skilled). On the other hand, 57 percent of the jobs created in the “Baltimore City” zone were high-skilled workers, while only 4 percent qualified as low-skilled. Low-skilled employment included construction, mining, and logging; semi-skilled included manufacturing, utilities, trade and transportation, leisure/hospitality, and other services; high-skilled included information, financial activities, education, health care, professional/scientific/technical, and business services. DLS based its skill categories off the framework created in Marcello M. Estevão and Evridiki Tsounta, “Has the Great RecessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. Raised U.S. Structural Unemployment?” International Monetary Fund, May 1, 2011, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Has-the-Great-Recession-Raised-U-S-24831.

[28] Maryland’s Baltimore City region employed the most community zone workers at 32 percent, likely because it is significantly larger than the other four zones and comprises a significant portion of the commercial and industrial areas of the city. Maryland’s other four zones all employed fewer than 15 percent community residents. Western Maryland’s zone employed 14 percent of workers from the zone community, Greater Baltimore Area 13 percent, Eastern Shore 8 percent, and Capital Region 6 percent. See Department of Legislative Services, Office of Policy Analysis, Maryland General Assembly, “Evaluation of the Enterprise Zone Tax Credit.”

[29] Louisiana Economic Development, “Enterprise Zone Program: 2009 Annual Report,” March 2010, https://www.opportunitylouisiana.com/assets/LED/docs/Performance_Reporting/2009_Annual_Report_Enterprise_Zone.pdf.

[30] See “Section 2.6: Equity motivations for place-based policies” in David Neumark and Helen Simpson, “Place-based policies.”.

[31] A study of California’s opportunity zones in the Bay Area showed that around 18.8 percent of tracts designated were in areas that had already seen “significant socioeconomic change” between 2000 and 2016, compared to only 2.7 percent of eligible tracts nationwide. The authors created a measure of investment that ranked tracts eligible for opportunity zone investment from 1 (lowest investment) to 10 (highest investment), based on a tract’s “current level of commercial, multifamily, single-family, and small-business investment.” They found that a quarter of the Bay Area’s zones were “among the most disinvested in the state,” but also that almost 40 percent of the Bay Area’s zones scored an 8 or higher on their investment ranking. The authors measured socioeconomic change in these tracts by examining characteristics like the average housing burden, median family income, and share of residents with a bachelor’s degree or higher. See Brett Theodos and Brady Meixell, “Assessing Governor Brown’s Selections for Opportunity Zones in the Bay Area,” Urban Institute, May 18, 2018, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/assessing-governor-browns-selections-opportunity-zones-bay-area. See also, an analysis by The Brookings Institution on the first 18 states to designate their zones. The authors found 22 percent of the selections were for areas with relatively low poverty rates (as opposed to “deeply impoverished”), and another 19 percent of the areas were what they considered to be already-gentrifying. Overall, they found 28 percent of the zones designated were either not poor, college campuses, or in areas where no one lived. See Adam Looney, “The Early Results of States’ Opportunity Zones Are Promising, but There’s Still Room for Improvement,” The Brookings Institution, April 18, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-early-results-of-states-opportunity-zones-are-promising-but-theres-still-room-for-improvement/.

[32] See Laura Strickler and Stephanie Ruhle, “Trump, Kushner, LeFrak could potentially benefit from federal ‘opportunity zones,’” NBC News, Dec. 12, 2018, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/trump-kushner-lefrak-could-potentially-benefit-federal-opportunity-zones-n946821.

[33] United States Government Accountability Office, “Revitalization Programs: Empowerment Zones, Enterprise Communities, and Renewal Communities,” March 12, 2010, https://www.gao.gov/assets/100/96577.pdf.

[34] Jim Tankersley, “Trump to Steer More Money to ‘Opportunity Zones,’” The New York Times, Dec. 12, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/12/us/politics/trump-opportunity-zones-tax-cut.html.

[35] Donald J. Trump, “Executive Order on Establishing the White House Opportunity and Revitalization Council,” The White House, Dec. 12, 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-establishing-white-house-opportunity-revitalization-council/.

[36] It’s worth noting that there is no lack of funds available for investment, especially when you consider global savings. And reforms that generally—as opposed to just for specific firms, industries, or areas—increase after-tax returns on capital can attract these savings for investment, which will create employment and increase wages. With a general approach, however, policymakers will be unable to predict exactly where this growth will occur. For this reason, research suggests the best way to increase opportunity for low-income individuals may be to reduce or remove barriers that keep low-income people from moving to more productive areas. For information on global savings and investment, see Gavin Ekins, “Time to Shoulder Aside ‘Crowding Out’ As an Excuse Not to Do Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 7, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/crowding-out-tax-reform/. https://taxfoundation.org/key-assumptions-dynamic-scoring/, and Stephen J. Entin, “Key Assumptions in Dynamic ScoringDynamic scoring estimates the effect of tax changes on key economic factors, such as jobs, wages, investment, federal revenue, and GDP. It is a tool policymakers can use to differentiate between tax changes that look similar using conventional scoring but have vastly different effects on economic growth. ,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 18, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/key-assumptions-dynamic-scoring/. For some research on mobility and opportunity, see David Schleicher, “Stuck! The Law and Economics of Residential Segregation,” The Yale Law Journal, October 2017, https://www.yalelawjournal.org/article/stuck-the-law-and-economics-of-residential-stagnation, and Edward L. Glaeser and Joshua D. Gottlieb, “The Economics of Place-Making Policies,” The Brookings Institution, October 2008, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2008/03/2008a_bpea_glaeser.pdf.

Share this article